Link Issues by Author

Over 175 subject matter experts in professions such as medicine, church ministry, archaeology, and diplomacy have authored Link issues since 1968.

Link Issues with Multiple Authors

AMEU's Long History

AMEU was founded in 1968 by Americans whose professions in medicine, church ministry, archaeology and diplomacy had taken them to the Middle East. AMEU strives to create in the United States a deeper appreciation of the cultures, histories, and politics of the region.

Our primary objective is to amplify the voices and analysis of scholars, activists, and policymakers working on Middle East issues, particularly the Israeli occupation of Palestine.

AMEU’s principal publication, The Link, is available in hard copy and online four or five times a year. Each issue is devoted to a single critical issue, one usually not covered in depth, if at all, in the mainstream press.

In addition to its general readership, The Link circulates to thousands of faith leaders, academics, and educators, as well as to hundreds of public and school libraries, including major universities. An annual voluntary subscription to The Link is $40.

While AMEU will continue to focus energies on The Link, new online forays will complement that print tradition. Our goal is to appeal to new readers and use digital tools to address and disseminate our content.

Catalog of all Link issues Since 1968

The Link archive constitutes a body of informed commentary, fact, and anecdotal evidence valuable for writers, researchers, and historians.

The New Face of Academic Freedom?

September 28, 2024 | AMEU | Multiple Author

The Time for Pious Words is Over

June 25, 2024 | AMEU | Current Issue

Ceasefire Now…Silence = Death

February 24, 2024 | AMEU | The Link

Woman, Life, Freedom

January 29, 2024 | George Mason University Expert Panel | The Link

AIPAC, Dark Money, and the Assault on Democracy

November 22, 2023 | Allan C. Brownfeld | The Link

The Politics of Archaeology – Christian Zionism and the Creation of Facts Underground

October 2, 2022 | Mimi Kirk | The Link

Apartheid…Israel’s Inconvenient Truth

February 2, 2022 | Chris McGreal | The Link

Israel’s Weaponization of Time

December 12, 2021 | Omar Aziz | The Link

Our Archive

September 12, 2021 | John Mahoney | The Link

On A RANT

July 20, 2021 | Sam Bahour | The Link

How Long Will Israel Get Away With It

April 9, 2021 | Haim Bresheeth-Zabner | The Link

The Decolonizing of Palestine Towards a One-State Solution

January 9, 2021 | Jeff Halper | The Link

Israelizing the American Police, Palestinianizing the American People

November 26, 2020 | Jeff Halper | The Link

The ONE-STATE REALITY and the REAL MEANING of ANNEXATION

August 23, 2020 | Ian Lustick | The Link

Palestinian Christians

June 6, 2020 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

UPDATED: The Latest on the Suspected Murderers of Alex Odeh

April 12, 2020 | David Sheen | The Link

The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine

February 29, 2020 | Rashid Khalidi | The Link

Fact and Fiction in Palestine

December 15, 2019 | Gil Maguire | The Link

Once Upon a Time in Gaza

November 10, 2019 | Rawan Yaghi | The Link

Uninhabitable: Gaza Faces Moment of Truth

October 5, 2019 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

What in God’s Name is going on?

April 14, 2019 | Edward Dillon | The Link

Jews Step Forward

January 31, 2019 | Marjorie Wright | The Link

Palestinian Children in Israeli Military Detention

December 15, 2018 | Brad Parker | The Link

The Judaization of Jerusalem Al-Quds

September 9, 2018 | Basem L. Ra'ad | The Link

Apartheid West Bank

June 6, 2018 | Jonathan Kuttab | The Link

Apartheid Israel

March 12, 2018 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

The Checkpoints

January 13, 2018 | Rawan Yaghi | The Link

Anti-Zionism Is Not Anti-Semitism, And Never Was

November 29, 2017 | Allan C. Brownfeld | The Link

The Cult of the Zionists – An Historical Enigma

August 20, 2017 | Thomas Suárez | The Link

Marwan Barghouti and the Battle of the Empty Stomachs

July 1, 2017 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

Al-Tamimi et al v. Adelson et al

April 1, 2017 | Fred Jerome | The Link

In The Beginning…

January 22, 2017 | John Mahoney | The Link

Wheels of Justice

December 3, 2016 | Steven Jungkeit | The Link

Agro-Resistance

August 14, 2016 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

The Murder of Alex Odeh

June 4, 2016 | Richard Habib | The Link

Protestantism’s Liberal/Mainline Embrace of Zionism

April 3, 2016 | Donald Wagner | The Link

The Second Gaza

January 10, 2016 | Atef Abu Saif | The Link

Between Two Blue Lines

October 31, 2015 | Tom Hayes | The Link

A Special Kind of Exile

August 15, 2015 | Alice Rothchild M.D. | The Link

Kill Bernadotte

June 13, 2015 | Fred Jerome | The Link

The Art of Resistance

March 7, 2015 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

The Window Dressers: The Signatories of Israel’s Proclamation of Independence

January 3, 2015 | Ilan Pappe | The Link

The Immorality Of It All

October 25, 2014 | Dr. Daniel C. Maguire | The Link

Can Palestine Bring Israeli Officials before the International Criminal Court?

August 16, 2014 | John B. Quigley | The Link

In Search of King Solomon’s Temple

June 9, 2014 | George Wesley Buchanan | The Link

Quo Vadis?

March 2, 2014 | Charles Villa-Vicencio | The Link

In Search of Grace Halsell

January 17, 2014 | Robin Kelley | The Link

Farewell, Figleaf

November 3, 2013 | Pamela Olson | The Link

What Israel’s Best Friend Should Know

August 24, 2013 | Miko Peled | The Link

Dimona—(Shhh! It’s A Secret.)

June 23, 2013 | John Mahoney | The Link

The Brotherhood

April 7, 2013 | Charles A. Kimball | The Link

Like a Picture, A Map is Worth A Thousand Words

January 28, 2013 | Rod Driver | The Link

When War Criminals Walk Free

November 18, 2012 | Dr. Mads Gilbert | The Link

Welcome to Nazareth

July 30, 2012 | Jonathan Cook | The Link

The Neocons… They’re Back

May 27, 2012 | John Mahoney | The Link

Is the Two-State Solution Dead?

March 28, 2012 | Jeff Halper | The Link

Mirror, Mirror

January 8, 2012 | Maysoon Zayid | The Link

Who Are the “Canaanites”? Why Ask?

November 19, 2011 | Basem L. Ra'ad | The Link

Palestine and the Season of Arab Discontent

September 1, 2011 | Lawrence R. Davidson | The Link

An Open Letter to Church Leaders

June 20, 2011 | David W. Good | 2011

Drone Diplomacy

May 1, 2011 | Geoff Simons | 2011

What Price Israel?

January 9, 2011 | Chris Hedges | 2011

Publish It Not

December 20, 2010 | Jonathan Cook | 2010

Shuhada Street

September 4, 2010 | Khalid Amayreh | 2010

Where Is The Palestinian Gandhi?

July 18, 2010 | Mazin Qumsiyeh | 2010

A Doctor’s Prescription for Peace with Justice

May 20, 2010 | Steven Feldman M.D. | 2010

The Olive Trees of Palestine

January 8, 2010 | Edward Dillon | 2010

Spinning Cast Lead

December 9, 2009 | Jane Adas | 2009

Ending Israel’s Occupation

September 23, 2009 | John Mahoney | 2009

L’Affaire Freeman

July 28, 2009 | James M. Wall | 2009

Righteous

April 2, 2009 | John Mahoney | 2009

Overcoming Impunity

January 26, 2009 | Joel Kovel | 2009

Captive Audiences: Performing in Palestine

December 18, 2008 | Thomas Suárez | 2008

Israeli Palestinians: The Unwanted Who Stayed

October 5, 2008 | Jonathan Cook | 2008

The Grief Counselor of Gaza

July 10, 2008 | Eyad Sarraj | 2008

State of Denial: Israel, 1948-2008

April 22, 2008 | Ilan Pappe | 2008

Hamas

January 6, 2008 | Khalid Amayreh | 2008

Collateral Damage

December 30, 2007 | Kathy Kelly | 2007

Avraham Burg: Apostate or Avatar?

October 4, 2007 | John Mahoney | 2007

Witness for the Defenseless

August 20, 2007 | Anna Baltzer | 2007

About That Word Apartheid

April 24, 2007 | John Mahoney | 2007

One Man’s Hope

January 7, 2007 | Fahim Qubain | 2007

Beyond the Minor Second

December 5, 2006 | Simon Shaheen | 2006

For Charlie

October 9, 2006 | Barbara Lubin | 2006

Why Divestment? Why Now?

August 20, 2006 | David Wildman | 2006

Inside the Anti-Occupation Camp

April 17, 2006 | Michel Warschawski | 2006

Middle East Studies Under Siege

January 14, 2006 | Joan W. Scott | 2006

A Polish Boy in Palestine

December 20, 2005 | David Neunuebel | 2005

The Israeli Factor

October 19, 2005 | John Cooley | 2005

The Coverage—and Non-Coverage—of Israel-Palestine

July 20, 2005 | Allison Weir | 2005

The Day FDR Met Saudi Arabia’s Ibn Saud

April 23, 2005 | Thomas W. Lippman | 2005

Iran

January 29, 2005 | Geoff Simons | 2005

When Legend Becomes Fact

December 21, 2004 | James M. Wall | 2004

Timeline for War

September 20, 2004 | John Mahoney | 2004

The CPT Report

June 16, 2004 | Peggy Gish | 2004

Mordechai Vanunu

April 22, 2004 | Mary Eoloff | 2004

Beyond Road Maps & Walls

January 1, 2004 | Jeff Halper | 2004

Rachel

December 5, 2003 | Cindy Corrie | 2003

Why Do They Hate US?

October 25, 2003 | John Zogby | 2003

In the Beginning, There Was Terrorism

July 5, 2003 | Ronald Bleier | 2003

Political Zionism

April 20, 2003 | John Mahoney | 2003

Veto

January 20, 2003 | Phyllis Bennis | 2003

The Making of Iraq

December 6, 2002 | Geoff Simons | 2002

A Most UnGenerous Offer

September 27, 2002 | Jeff Halper | 2002

The Crusades, Then and Now

July 5, 2002 | Robert Ashmore | 2002

A Style Sheet on the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

April 2, 2002 | J. Martin Bailey | 2002

Law & Disorder in the Middle East

January 15, 2002 | Francis A. Boyle | 2002

Reflections on September 11, 2001

November 20, 2001 | James M. Wall | 2001

Inside H-2 [Hebron]

September 12, 2001 | Jane Adas | 2001

Americans Tortured in Israeli Jails

June 8, 2001 | Jerri Bird | 2001

Today’s Via Dolorosa

April 20, 2001 | Edward Dillon | 2001

Israel’s Anti-Civilian Weapons

January 1, 2001 | John Mahoney | 2001

Confronting the Bible’s Ethnic Cleansing in Palestine

December 17, 2000 | Michael Prior, C.M. | 2000

On the Jericho Road

September 5, 2000 | AMEU | 2000

The Lydda Death March

July 13, 2000 | Audeh Rantisi | 2000

The Syrian Community on the Golan Heights

April 27, 2000 | Bashar Tarabieh | 2000

Muslim Americans in Mainstream America

February 20, 2000 | Nihad Awad | 2000

Native Americans and Palestinians

December 20, 1999 | Norman Finkelstein | 1999

Iraq: Who’s To Blame?

October 3, 1999 | Geoff Simons | 1999

Secret Evidence

July 20, 1999 | John Sugg | 1999

The Camp

May 20, 1999 | Muna Hamzeh-Muhaisen | 1999

Sahmatah

February 20, 1999 | Edward Mast | 1999

Dear NPR News

December 18, 1998 | Ali Abunimah | 1998

Israel’s Bedouin: The End of Poetry

September 22, 1998 | Ron Kelley | 1998

Politics Not As Usual

July 8, 1998 | Rod Driver | 1998

Israeli Historians Ask: What Really Happened 50 Years Ago?

January 8, 1998 | Ilan Pappe | 1998

The Jews of Iraq

January 8, 1998 | Naeim Giladi | 1998

“People and the Land’: Coming to a PBS Station Near You?

November 12, 1997 | Tom Hayes | 1997

U. S. Aid to Israel: The Subject No One Mentions

September 1, 1997 | Richard Curtiss | 1997

Remember the [USS] Liberty

July 24, 1997 | John Borne | 1997

AMEU’s 30th Anniversary Issue

April 8, 1997 | AMEU | 1997

The Children of Iraq: 1990-1997

January 22, 1997 | Kathy Kelly | 1997

Slouching Toward Bethlehem 2000

December 16, 1996 | J. Martin Bailey | 1996

Deir Yassin Remembered

September 2, 1996 | Dan McGowan | 1996

Palestinians and Their Days in Court: Unequal Before the Law

July 22, 1996 | Linda Brayer | 1996

Meanwhile in Lebanon

April 8, 1996 | George Irani | 1996

Hebron’s Theater of the Absurd

January 8, 1996 | Kathleen Kern | 1996

Epiphany at Beit Jala

November 24, 1995 | Donald Neff | 1995

Teaching About the Middle East

September 19, 1995 | Elizabeth Barlow | 1995

Jerusalem’s Final Status

July 8, 1995 | Michael Dumper | 1995

A Survivor for Whom Never Again Means Never Again [An Interview with Israel Shahak]

May 1, 1995 | Mark Dow | 1995

In the Land of Christ Christianity Is Dying

January 24, 1995 | Grace Halsell | 1995

Refusing to Curse the Darkness

December 8, 1994 | Geoffrey Aronson | 1994

Humphrey Gets the Inside Dope

September 29, 1994 | John Law | 1994

The Post-Handshake Landscape

July 19, 1994 | Frank Collins | 1994

Bosnia: A Genocide of Muslims

May 8, 1994 | Grace Halsell | 1994

Will ’94 Be ’49 All Over Again?

January 22, 1994 | Rabbi Elmer Berger | 1994

The Exiles

December 18, 1993 | Ann Lesch | 1993

Save the Musht

October 8, 1993 | Rosina Hassoun | 1993

Censored

August 8, 1993 | Colin Edwards | 1993

An Open Letter to Mrs. Clinton

May 8, 1993 | James Graff | 1993

Islam and the US National Interest

February 8, 1993 | Shaw Dallal | 1993

A Reply to Henry Kissinger and Fouad Ajami

December 16, 1992 | Norman Finkelstein | 1992

Beyond Armageddon

October 8, 1992 | Don Wagner | 1992

Covert Operations: The Human Factor

August 8, 1992 | Jane Hunter | 1992

AMEU’s 25th Anniversary Issue

May 19, 1992 | John Mahoney | 1992

Facing the Charge of Anti-Semitism

January 20, 1992 | Paul Hopkins | 1992

The Comic Book Arab

December 12, 1991 | Jack Shaheen | 1991

Visitation at Yad Vashem

September 3, 1991 | James Burtchaell | 1991

A New Literary Look at the Middle East

August 25, 1991 | John Mahoney | 1991

Beyond the Jewish-Christian Dialogue: Solidarity with the Palestinian People

February 8, 1991 | Marc Ellis | 1991

The Post-War Middle East

January 2, 1991 | Rami Khouri | 1991

Arab Defamation in the Media

December 21, 1990 | Casey Kasem | 1990

What Happened to Palestine?: The Revisionists Revisited

September 17, 1990 | Michael Palumbo | 1990

Protestants and Catholics Show New Support for Palestinians

July 26, 1990 | Charles A. Kimball | 1990

My Conversation with Humphrey

April 2, 1990 | John Law | 1990

American Victims of Israeli Abuses

January 17, 1990 | Albert Mokhiber | 1990

Diary of an American in Occupied Palestine

November 8, 1989 | Mary Mary | 1989

The International Crimes of Israeli Officials

September 23, 1989 | John B. Quigley | 1989

An Interview with Ellen Nassab

July 8, 1989 | Hisham Ahmed | 1989

US Aid to Israel

May 23, 1989 | Mohamed Rabie | 1989

Cocaine, Cutouts: Israel’s Unseen Diplomacy

January 14, 1989 | Jane Hunter | 1989

The Shi’i Muslims of the Arab World

December 8, 1988 | Augustus Norton | 1988

Israel and South Africa

October 3, 1988 | Robert Ashmore | 1988

Zionist Violence Against Palestinians

September 8, 1988 | Mohammad Hallaj | 1988

Dateline: Palestine

June 25, 1988 | George Weller | 1988

The US Press and the Middle East

January 8, 1988 | Mitchell Kaidy | 1988

The US Role in Israel’s Arms Industry

December 8, 1987 | Bishara Bahbah | 1987

The Shadow Government

October 24, 1987 | Jane Hunter | 1987

Public Opinion and the Middle East Conflict

September 8, 1987 | Fouad Moughrabi | 1987

England And The US in Palestine: A Comparison

May 22, 1987 | W. F. Aboushi | 1987

Archaeology Politics in Palestine

January 11, 1987 | Leslie Hoppe | 1987

The Demographic War for Palestine

December 21, 1986 | Janet Abu-Lughod | 1986

Misguided Alliance

October 21, 1986 | Cheryl Rubenberg | 1986

The Vatican, US Catholics, and the Middle East

August 5, 1986 | George Irani | 1986

The Making of a Non-Person

May 2, 1986 | Jan Abu Shakrah | 1986

The Israeli-South African-US Alliance

January 17, 1986 | Jane Hunter | 1986

Humphrey Goes to the Middle East

December 4, 1985 | John Law | 1985

US-Israeli-Central American Connection

November 23, 1985 | Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi | 1985

The Palestine-Israel Conflict in the US Courtroom

September 1, 1985 | Rex Wingerter | 1985

The Middle East on the US Campus

May 24, 1985 | Naseer Aruri | 1985

From Time Immemorial: The Resurrection of a Myth

January 12, 1985 | Mohammad Hallaj | 1985

The Lasting Gift of Christmas

December 29, 1984 | Hassan Haddad | 1984

Israel’s Drive for Water

November 25, 1984 | Leslie Schmida | 1984

Shrine Under Siege

August 21, 1984 | Grace Halsell | 1984

The USS Liberty Affair

May 6, 1984 | James Ennes Jr. | 1984

The Middle East Lobbies

January 21, 1984 | Cheryl Rubenberg | 1984

US Aid to Israel

December 23, 1983 | Samir Abed-Rabbo | 1983

Christian Zionism

November 18, 1983 | O. Kelly Ingram | 1983

Prisoners of Israel

August 22, 1983 | Edward Dillon | 1983

The Land of Palestine

May 11, 1983 | L. Dean Brown | 1983

Military Peacekeeping in the Middle East

January 5, 1983 | William Mulligan | 1983

US-Israeli Relations: A Reassessment

December 20, 1982 | Allan Kellum | 1982

The Islamic Alternative

September 5, 1982 | Yvonne Haddad | 1982

Yasser Arafat: The Man and His People

July 9, 1982 | Grace Halsell | 1982

Tourism in the Holy Land

May 5, 1982 | Larry Ekin | 1982

Palestine: The Suppression of an Idea

January 18, 1982 | Mohammad Hallaj | 1982

The Disabled in the Arab World

December 14, 1981 | Audrey Shabbas | 1981

Arms Buildup in the Middle East

September 26, 1981 | Greg Orfalea | 1981

The Palestinians in America

July 5, 1981 | Elias Tuma | 1981

A Human Rights Odyssey: In Search of Academic Freedom

April 23, 1981 | Michael Griffin | 1981

Europe and the Arabs: A Developing Relationship

January 12, 1981 | John Richardson | 1981

National Council of Churches Adopts New Statement on the Middle East

December 20, 1980 | Allison Rock | 1980

Kuwait: Prosperity From A Sea of Oil

September 7, 1980 | Alan Klaum | 1980

American Jews and the Middle East: Fears, Frustration and Hope

July 24, 1980 | Allan Solomonow | 1980

The Arab Stereotype on Television

April 22, 1980 | Jack Shaheen | 1980

The Presidential Candidates: How They View the Middle East

January 13, 1980 | Allan Kellum | 1980

The West Bank and Gaza: The Emerging Political Consensus

December 16, 1979 | Ann Lesch | 1979

The Muslim Experience in the US

September 5, 1979 | Yvonne Haddad | 1979

Jordan Steps Forward

July 22, 1979 | Alan Klaum | 1979

The Child in the Arab Family

May 30, 1979 | Audrey Shabbas | 1979

Palestinian Nationhood

January 12, 1979 | John Mahoney | 1979

The Sorrow of Lebanon

December 22, 1978 | Youssef Ibrahim | 1978

The Arab World: A New Economic Order

October 5, 1978 | Youssef Ibrahim | 1978

The Yemen Arab Republic: From Behind the Veil

May 20, 1978 | Alan Klaum | 1978

The New Israeli Law: Will It Doom the Christian Mission in the Holy Land?

April 24, 1978 | Humphrey Walz | 1978

The Palestinians

January 14, 1978 | John Sutton, ed. | 1978

War Plan Ready If Peace Effort Fails

December 19, 1977 | Jim Hoagland | 1977

Concern Grows in U.S. Over Israeli Policies

September 25, 1977 | Allan C. Brownfeld | 1977

Prophecy and Modern Israel

June 5, 1977 | Calvin Keene | 1977

Literary Look at the Middle East

April 16, 1977 | Djelloul Marbrook | 1977

Carter Administration & the Middle East

January 8, 1977 | Norton Mezvinski | 1977

Unity Out of Diversity: United Arab Emirates

December 19, 1976 | John Sutton, ed. | 1976

New Leader for Troubled Lebanon

October 5, 1976 | Minor Yanis | 1976

Egypt: Rediscovered Destiny – A Survey

July 5, 1976 | Alan Klaum | 1976

America’s Stake in the Middle East

June 5, 1976 | John Davis | 1976

Islamic/Christian Dialogue

January 12, 1976 | Patricia Morris, ed. | 1976

Zionism? Racism? What Do You Mean?

December 21, 1975 | Humphrey Walz | 1975

Syria

October 8, 1975 | Marcella Kerr, ed. | 1975

Saudi Arabia

June 20, 1975 | Ray Cleveland | 1975

The West Bank and Gaza

April 16, 1975 | John Richardson | 1975

Crisis in Lebanon

January 8, 1975 | Jack Forsyth | 1975

The Arab-Israeli Arms Race

December 14, 1974 | Fuad Jabber | 1974

The Palestinians Speak. Listen!

October 12, 1974 | Frank Epp | 1974

Holy Father Speaks on Palestine

May 26, 1974 | Pope Paul VI | 1974

History of the Middle East Conflict

March 18, 1974 | Sen. James Abourezk | 1974

Arab Oil and the Zionist Connection

January 21, 1974 | Jack Forsyth | 1974

Christians in the Arab East

December 8, 1973 | Humphrey Walz | 1973

American Jewry and the Zionist Jewish State Concept

September 30, 1973 | Norton Mezvinski | 1973

US Middle East Involvement

May 8, 1973 | John Richardson | 1973

A Prophet Speaks in Israel

March 8, 1973 | Norton Mezvinski | 1973

The Arab Market: Opportunities for U.S. Business

January 21, 1973 | Humphrey Walz | 1973

Toward a More Open Middle East Debate

December 2, 1972 | Humphrey Walz | 1972

Some Thoughts on Jerusalem

September 15, 1972 | Joseph Ryan | 1972

Foreign Policy Report: Nixon Gives Massive Aid But Reaps No Political Harvest

May 13, 1972 | Andrew Glass | 1972

A Look at Gaza

March 2, 1972 | Humphrey Walz | 1972

Religion Used to Promote Hatred in Israel

January 2, 1972 | Humphrey Walz | 1972

Computer Age Answers to M. E. Problems

December 18, 1971 | Humphrey Walz | 1971

Peace and the Holy City

September 5, 1971 | Humphrey Walz | 1971

Invitation to the Holy Land

July 1, 1971 | Humphrey Walz | 1971

Why Visit the Middle East?

May 15, 1971 | Humphrey Walz | 1971

Arab-Israeli Encounter in Jaffa

March 12, 1971 | Humphrey Walz | 1971

Is the Modern State, Israel, A Fulfillment of Prophecy?

December 6, 1970 | Bradley Watkins | 1970

Council of Churches Acts on Middle East Crisis

September 26, 1970 | Humphrey Walz | 1970

Mayhew Reports on Arab-Israeli Facts

May 24, 1970 | Christopher Mayhew | 1970

Sequel Offered Free to Refugee Agencies

March 22, 1970 | Humphrey Walz | 1970

Responses to Palestine Information Proposal

January 3, 1970 | Humphrey Walz | 1970

Churches Plan for Refugees and Peace

December 15, 1969 | Humphrey Walz | 1969

End UNRWA Deficit for Refugee Aid

September 28, 1969 | Humphrey Walz | 1969

Church Statement Stresses Mideast Needs

May 3, 1969 | Humphrey Walz | 1969

Mosque to Add Minaret to NYC Skyline

March 9, 1969 | Humphrey Walz | 1969

Black Bids New Administration Face Facts

January 3, 1969 | Humphrey Walz | 1969

UN Struggles for Mideast Peace

November 3, 1968 | Humphrey Walz | 1968

How The Link Was Born and Can Grow

September 1, 1968 | AMEU | 1968

| Also in this issue: In Appreciation: Donald Neff, 1930-2015 |

By Basem L. Ra’ad

At last year’s Toronto Palestinian Film Festival, I attended a session entitled “Jerusalem, We Are Here,” described as an interactive tour of 1948 West Jerusalem. It was designed by a Canadian-Israeli academic specifically as a virtual excursion into the Katamon and Baqʿa neighborhoods, inhabited by Christian and Muslim Palestinian families before the Nakba — in English, the Catastrophe.

Little did I anticipate the painful memories this session would bring. The tour starts in Katamon at an intersection that led up to the Semiramis Hotel. The hotel was blown up by the Haganah on the night of 5-6 January 1948, killing 25 civilians, and was followed by other attacks intended to vacate non-Jewish citizens from the western part of the city. Not far from the Semiramis is the house of my grandparents, a three-story building made of stone that my grandfather, a stone mason, had designed for the future growth of the family. It still stands today. I visited the location recently and found it occupied by Israelis, who never compensated my grandparents or even asked permission. My parents and their children lived nearby in Baqʿa. Then on April 9 the Irgun and Stern gangs executed the massacre at Deir Yassin which, combined with other Zionist plans for depopulation (the last Plan D or Dalet), led to the complete exodus of Palestinians from West Jerusalem and surrounding villages, as well as hundreds of towns and villages in Palestine. Our family and almost 30,000 West Jerusalem Palestinians, plus 40,000 from nearby villages, adding up to more than 726,000 from throughout Palestine (close to 900,000 according to other U.N. estimates) were forced into refugee status and not allowed to return to their homes.

The true story of West Jerusalem is far from what Zionist propaganda portrays to justify the expulsion of its Palestinian inhabitants: an “Arab attack” against which the Jews held bravely, rich Palestinians escaping on the first sign of violence, then being overwhelmed by Jewish immigrants whom the Israelis were forced to let stay in vacated Arab houses—or other similar tales.

In 1995, I made a “return” to Palestine by virtue of a foreign passport that allowed me to enter on a three-month visa. I was obliged to leave at the end of each three-month period and to rent accommodations. It was not always easy to get the usual three months, and I wasn’t allowed to renew my stay internally, though the Ministry of Interior gives renewals to other holders of foreign passports for those not of Palestinian origin. I faced restrictions and received none of the privileges accorded to Jews, born elsewhere, who wished or were recruited to come to the country of my birth. By this time, my grandparents and my parents had died and were buried in Jordan. East Jerusalem has been occupied since 1967, and the whole of geographic Palestine controlled by Israel.

Before crossing, I searched the papers kept by my brother in Jordan and discovered two documents: one related to a parcel of land my parents had purchased in the early 1940s, and the other a deed to a piece of land on the way to Beth Lahm/Bethlehem my father acquired in 1954 (in “the West Bank,” then under Jordanian rule), perhaps thinking of it as a substitute for the loss in 1948. In searching for the first parcel, I was told a request for information has to go to a Tel Aviv office, though I’m pretty sure it would be found to be classified under the Absentees’ Property Law and thus already expropriated by the Israelis.

I then started looking for the second parcel. No one seemed to know about it; the Israeli municipal office said it did not exist. Months passed when by accident I raised the subject with a colleague who told me she heard about that area and that I should check with an old man who lives near New Gate. The man indeed had maps and documents for the parcels in that development. He told me that after 1967 he lost contact with some landowners who lived on the other side of the Jordan river, that the whole hillside was expropriated by the Israeli government in 1970 to build the colony of Gilo. He showed me letters that he as a representative had written to various governments, to the U.N., to the Pope, to any organization he thought could help, to no avail.

To recall such events highlights a small part of the enormity of the Palestinian Nakba. Depopulating Palestinians from West Jerusalem was part of the process of destruction and ethnic cleansing of scores of cities and towns and hundreds of villages throughout the whole of Palestine, documented in Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains and Ilan Pappe’s Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. The Arab countries were half-hearted in their interference on May 15, with ill-equipped armies and foreign-influenced governments; the Palestinians were unprepared and poorly mobilized to deal with a well-planned Zionist invasion, their resources and much of the leadership having been decimated by the British in the 1936-39 uprising. The Zionist plan has continued to operate and expand until today, pursuing its objective for control of all of Palestine, in spite of Israel having agreed to the U.N. partition plan leading to two states and to the return of Palestinian refugees as a condition for Israel’s acceptance as a member of the U.N.

What happened in West Jerusalem in 1948 is today sidelined by the attention given to occupied East Jerusalem, with the issues shifted in focus to make it appear as if the “dispute” is now only about the “West Bank” and “East Jerusalem.” To begin with West Jerusalem is to emphasize that any eventual solution must account for it as part of the refugee issue, which also includes other cities like Yafa and Haifa and hundreds of villages throughout the country, either destroyed (as with most of them), replaced by colonies, or kept intact as in the old homes now inhabited by Israelis without regard for the original owners (in places like ‘Ein Hawd/Ein Hod and ‘Ein Karem).

This essay analyses the claim Israel used for taking Palestinian land, and details Israel’s Judaizing actions within the city and outside in the expanded municipal boundaries where several Jewish colonies have been built. It discusses the most blatant “laws” enacted by Israel to provide legal cover for its takeover of land and properties and its measures to control the city’s demography by applying discriminatory regulations on residency.

The Zionist Claim System

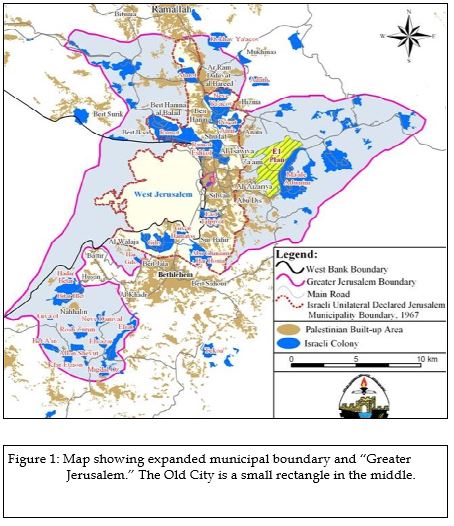

When considering historical Jerusalem, we think of the small area now called the Old City, contained within the Ottoman walls completed in 1541. It is less than one square kilometer, compared to the city’s current self-declared Israeli boundaries, which encompass 123 square kilometers. In the map (Figure 1) the Old City is the barely noticeable rectangle in the middle. Before June 1967, Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem, along with suburbs outside the wall, measured only 6 square kilometers, while West Jerusalem covered 32 square kilometers. The boundaries that existed until 1967 were the result of the 1949 Armistice Agreement. The “green line” then violated the stipulation in the U.N. partition resolution that Jerusalem and surrounding areas be designated as a “corpus separatum.” The city’s internationalization as a kind of Vatican, affirmed in later resolutions, still informs the special status of various consulates, and points to the specific impropriety of the recent U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

The Zionist claim system, which was developed and adapted over more than a hundred years, was preceded for centuries by a somewhat similar Western claim system. The identification with biblical narratives was useful in providing a religious rationale for colonial and racial theories, starting with the discovery of the New World and expanding across the world starting in the sixteenth century. Accounts like Exodus and “the Conquest of Canaan” drove colonial projects in North America, Australia and South Africa. Colonists in what became the U.S. and Canada transferred biblical typology to construct a myth of exceptionalism—as God’s Chosen People entitled to conquer, dispossess, and exterminate millions of indigenous inhabitants. Later in the 19th century emerged a movement called “sacred geography” as a literal tracing in the “Holy Land” to salvage old religious understanding against the discoveries that undermined biblical historicity. It produced hundreds of travel accounts of Palestine and semi-scholarly works of “biblical archaeology” that prepared the ground for Zionism. This antiquated model for dispossession is now alive in “the Holy Land,” and has revived similar entitlements.

Fixating on Old Testament narratives and exaggerated connections, Zionist claims about Palestine go something like this: followers of Judaism about 2,000 years ago are the same as Jews today, which gives today’s Jews the right to occupy Palestinian land because of promises inserted in the Bible, which they interpret as given to them by “God.” Hebrew is seen as a very ancient language that goes back to the presumed time of Moses and before him Abraham, although it did not exist in those periods but was a later appropriation of other languages and scripts such as Phoenician and Aramaic.

Zionist arguments encompass a whole complex of assumptions and fabrications which, to be realized, have had to take over aspects of continuity available only in the people who lived on the land, the Palestinians. In Hidden Histories, under “claims” and “appropriation,” I cite more than 40 refutable claims and appropriations that cover aspects involving biblical stories, stipulated connections between present Jews and ancient Jews, or Israelites, as well as a range of fabricated or exaggerated ascriptions related to culture, foods, plants, sites, place names, languages, scripts, and other elements. These appropriations create a false nativity, magnifying Jewish connections and undermining or demonizing ancient and modern peoples. In this context, Palestinian existence and continuity over many millennia become invisible, camouflaged by this claim system through strategies of dismissal or justification (e.g., Palestinians are Muslims who came from the Arabian Peninsula, so don’t have the same ancient connections.)

Discoveries since the 19th century have debunked the historicity of a host of notions underpinning this Zionist system. Epigraphic and archaeological finds show that biblical accounts, such as the story of Nūh/Noah, were copied from more ancient regional myths, such as the story of the Mesopotamian flood . Among scholars who have come to these conclusions are Israelis, like archaeologist Ze’ev Herzog who summarizes as follows: “The patriarchs’ acts are legendary… the Israelites were never in Egypt, did not wander in the desert, did not conquer the land in a military campaign and did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel. Perhaps even harder to swallow is the fact that the united monarchy of David and Solomon, which is described by the Bible as a regional power, was at most a small tribal kingdom. And it will come as an unpleasant shock to many that the God of Israel, Jehovah, had a female consort.”

Contrary to common impressions, people in Palestine were predominantly polytheistic in their religion, mostly Phoenicians, Greeks and Arab tribes. People in the region may have transitioned from one religion to the next, but they in general stayed where they were. Further, “exile” is “a myth” and the notion of a “Jewish people” is a historical fantasy, as shown by Arthur Koestler, Shlomo Sand and others. Nor are present Jews connected in any real way to ancient Jews or to “Israelites” and “Hebrews.” For present Jews to make these ancient links is like Muslims in Afghanistan or Indonesia saying they descend from Prophet Muhammad and have ownership rights to Mecca and Arabia as their ancestral homeland.

The Stones of Others: Israeli Judaizing Actions

Plans were ready, existing “laws” in place, new “laws” conveniently enacted for how to take over the stones built by other people and to control the demographics. It is a grand strategy that appears to have been prepared well in advance.

Judaizing the city has proceeded through expropriations within and outside the walls, expansion of the Jewish Quarter, establishing enclaves elsewhere in the Old City, ringing the city with colonies within arbitrarily expanded boundaries, manipulating a Jewish majority through measures to limit or reduce the Palestinian population by excluding/including areas using the separation wall, restricting family reunification and child registration, revoking residency status (see sections below), refusing permits, demolitions, and other regulations to constrain Palestinian building and development. These measures are being taken in addition to changes to street and place names that use Hebrew above Arabic and English names, changes made by committees which, in most cases, distort the original Arabic names into Hebrew phonetics.

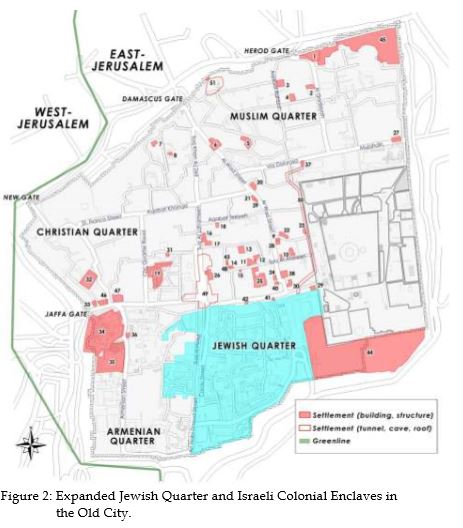

Only three days after the June 1967 war ended, the Israelis demolished Hāret al-Maghāriba, Maghribi (Moroccan) Quarter, which dates back to the 12th century, in order to clear the area for a plaza in front of the Western or Wailing Wall. By June 11 the quarter was totally leveled, 135 houses demolished and 650 residents evicted. Among the demolished buildings were a mosque, Sufi prayer halls, and hostels. The renowned Khanqah al-Fakhriyya, adjacent to the Western Wall, a Sufi compound, was destroyed two years later by Israeli archaeological excavations. During the destruction of the quarter some residents refused to leave and stayed until just before the building collapsed. One woman was found dead in the rubble.

In 1968, Israel started the project to settle and expand the Jewish Quarter. As Meron Benvenesti and Michael Dumper point out, prior to 1948, the Jewish Quarter was less than 20% owned by Jews since most buildings were leased from the Islamic waqf or private family waqfs. While Jewish immigrants increased outside the city walls, in the quarter the Jewish population had declined well before 1948. At the end of fighting those who had stayed were removed to Israeli-held areas, the buildings partially used to house some West Jerusalem Palestinian refugees. Zionist writers make a point of repeating that this happened, that Jews had no access to the Western Wall or Mount of Olives between 1948 and 1967, a by-product of the conflict and hostilities; they forget that hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were evicted from West Jerusalem, other cities, towns and villages, their property taken, and that Israel had refused to allow any of them to return.

To implement this expansion, Israel expropriated more than 32 acres of Islamic and private Palestinian property, using the 1943 British ordinance and Absentees’ Property Law, between the Maghribi Quarter and the Armenian Convent, and from the Tarīq Bab al-Silsilah in the north to the city walls in the south. That included 700 stone buildings, of which only 105 had been owned by Jews before 1948. Palestinian property seized included 1,048 apartments and 437 workshops and commercial stores. (Even then-mayor of West Jerusalem Teddy Kollek objected, saying hundreds will lose their livelihood and thousands dispersed and, citing the expulsion of Palestinians from West Jerusalem in 1948, wondered when they would reclaim their property.)

Owners and those evicted were offered compensation, but the offer was essentially meaningless since waqf property trustees are prevented by shariʿah law from accepting any change in property status. The process took several years since most refused compensation. This resulted in litigation along with harassment and coercion. As still happens in takeovers, people who refuse have their entry blocked, surroundings demolished and are subjected to annoyances such as drilling and falling masonry.

In addition to the above, two other drastic developments occurred over the coming years: inserting enclaves in the Old City and building colonies around the city’s expanded municipal boundaries.

The enclaves within the Old City exhibit extreme ill-intention and are a constant source of tension. Other than the expanded Jewish Quarter, at least 78 properties within the walls have been seized and made into fortresses or mini-colonies. Figure 2, a partial indication with numbers, shows the extent of this cancerous infiltration. With government assistance and foreign Jewish money, extremist groups took over properties, using various pretexts and acquisition tricks, among them to locate and occupy properties previously owned or leased by Jews, remove protected Palestinian tenants, coerce tenants to sublet, and acquire by shady purchases that hide the source.

The drive by militant groups to establish a presence in the Muslim Quarter intensified after the rise of Likud and after Ariel Sharon, who was then Minister of Housing, in 1987, took hold of an apartment in a property in Al Wad Street owned by a Jewish Belarusian in the 1880s. (It is as if anything owned or leased by a Jew can be re-owned by any Jew, contrary to what is applicable to homes that were emptied of Palestinians in 1948 whose direct owners can’t claim them.) The drive for infiltration and acquisition has recently also been active in areas close to Jaffa Gate and around the periphery of the enlarged Jewish Quarter, it seems with the intention of expanding it further at the expense of the Muslim and Christian quarters.

Outside the Old City, as early as 1968, 17,300 acres were annexed to the municipal boundaries. These included the lands of 28 villages and some parts of Beit Lahm (Bethlehem), Beit Jala and Beit Sahour municipalities. Much more confiscation occurred in the West Bank, and by now in addition to all the colonies in the West Bank, in the area called Greater Jerusalem scores of Jewish-only colonies, which are increasing in number have been built of various sizes, some already cities, all the result of confiscation of mostly private land, as well as communal or public lands.

Colonies constructed since 1968 within the Israeli-declared Jerusalem municipality itself, include: Ramat Eshkol, French Hill or Givʿat Shapira (both on 1,186 acres, expropriated mostly from Sheikh Jarrah), Sanhedria Murhevet, Givʿat HaMivtar, Gilo (on land belonging to residents of Bethlehem, Beit Jala, Beit Safafa and Sharafat), Neve Ya‘akov (using the pretext of 16 Jewish-owned acres before 1948, Israel confiscated 3,500 acres of privately owned and titled Palestinian land for “public purposes”), Givʿat Hamatos, Ramot Alon (expropriated from Beit Iksa and Beit Hanina), Ma’alot Dafna (485 dunums expropriated from East Jerusalem and no-man’s land), East Talpiot (on more than a fifth of Sur Baher land), Pisgat Ze’ev (1,112 acres, seized from villagers of Beit Hanina, Hizma and Anata), Pisgat Amir (expropriated from the Palestinian village of Hizma), Ramat Shlomo called Reches Shuʿfat earlier (expropriated from Shuʿfat), Har Homa (1,300 dunums seized from private land owners from Beit Sahour and Sur Baher), Nof Zion (extending into the heart of the Palestinian neighborhood of Jabal el Mukabber), and Mamilla.

In the early 1970s, just outside the Israeli-declared municipal boundaries of Jerusalem, colonial growth proceeded at an equally brisk pace, with Ma‘aleh Adumim on lands confiscated from the town of Abu Dees achieving city status in 1991,with about 40,000 inhabitants.

Despite the Oslo Agreement, the Israeli government in 1995 started discussion of the “Greater Jerusalem” Master Plan with an outer ring of colonies, including Ma‘aleh Adumim, Givʿat Ze’ev (on public land, the site of a Jordanian camp), Har Adar (confiscated from Palestinian lands of Beit Surik and Qatanna), Kochav Yaʿakov and Tel Zion (on thousands of dunums confiscated from Palestinian villages of Kafr ʿAqab and Burqa), settlements east of Ramallah, Israeli buildings in Ras el-ʿAmud, Efrat, the Etzion Bloc and Beitar Illit—extending over more than 300 sq. km. of the West Bank. Such a Greater Jerusalem is aimed at strengthening Israeli domination in the central West Bank by adding 19 colonies into Jerusalem and a population of more than 150,000 Jews—for sure to finally kill any prospect for the establishment of a viable Palestinian state.

In 2017, a bill for Greater Jerusalem was introduced for a vote in the Knesset, and would likely have been approved except for some apparent U.S. and European pressure. It is clear, however, that the Israeli government and city officials are taking advantage of Trump’s policies to “push, push, push,” as one of them said, and to accelerate their building rampage and take other Judaizing measures while they have a freer hand.

Silwān has become another focus of Israeli acquisition, partly as a result of relative limitation in further expansion of enclaves within the Old City. Silwān is a town of about 35,000 Palestinian residents that borders the southern wall of the Old City. It is associated in part with what is called “the City of David.” Evidence points to continuous habitation since the fourth millennium BCE, but the fixation has been with the presumed Israelite period and the conquest by David. A Zionist archaeologist, Eilat Mazar, has claimed discovery of what remains from David’s palace, though many Israeli archaeologists say the findings contradict this claim.

The takeovers have accelerated in particular in the area called Wadi Hilweh and in al-Bustan neighborhood. Private, well-funded right-wing Zionist organizations such as Elad, as well as the Jewish National Fund, are used by the government, which hands over properties to them and protects their designs to control buildings and develop methods to settle Jews and dislocate Palestinians. Most properties in Silwān have been seized using the Absentees’ Property Law, though technically East Jerusalem had been declared by Israel to be exempt from it.

Elad has been given power by the government to run the “City of David National Park,” thus archaeological excavations are employed as another excuse to expropriate more Palestinian private land and to rewrite historical memory by misinterpreting and falsifying results. (A Byzantine water pit becomes the pit into which Jeremiah was thrown, according to Elad guides.) Plans for an archaeological/amusement park will lead to further destruction of Palestinian neighborhoods. By creating an archaeological tourist park dominated by extremist elements, Israel is intent on maintaining an exclusivist national narrative, the inventiveness about “David” being limitless.

This “Davidization” is going apace in other parts of the city, with an apparent design to join Silwān to the Jewish Quarter and the Tower of David area. In this effort to solidify an invented narrative, there has been a shift in the visualization of Jerusalem and its perception for tourists and Israelis, re-centering the gaze on the Tower of David and wielding new architecture and memorabilia to it, as argued by Dana Hercbergs and Chaim Noy (“Beholding the Holy City: Changes in the Iconic Representation of Jerusalem in the 21th Century”). Certainly, this narrative of making the Tower of David a museum of “Jewish history” is not only contradicted by its archaeology and history, but also by 17th-century minaret that tops the citadel and makes it a “tower”—though few tourists would raise a question. The mushrooming of Davids during the last decades has occurred with the speed and multiplication of other malignancies.

Laws

“Laws” have been issued ever since the beginning of the Israeli state in 1948 that have accumulated and intensified in their design to dispossess the Palestinian population and entrench Zionist exclusivity—a web of laws that can only be described as a parody in any sense of legality.

It’s a one-sided process. Where convenient, Israel has employed British mandatory land regulations, such as the 1943 Land Ordinance, and even Ottoman laws, to implement its expansion by expropriation. Other than the “right of return” for any Jew, the reverse of which is no return for any Palestinian forced to leave, the most flagrant legal tool is the Absentees’ Property Law (1950), signed by David Ben-Gurion as prime minister and Chaim Weizmann as president. The other instrumental laws were the Land Acquisition Law in 1953 and the Planning and Construction Law of 1965, which more or less completed the process of expropriation, though more disinheriting laws continue to be issued until today.

The 1950 law was devised for the purpose of disinheriting Palestinians and preventing their retrieval of properties (or their return), in order to establish Israeli control of land or houses and buildings owned by Palestinian refugees in cities, towns and destroyed or depopulated villages. It also applies to furnishings and valuables, bank accounts and other holdings, covering persons as “absentee” and property as “absentee property” even when “the identity of an absentee is unknown.”

An absentee’s dependent does not have rights if she/he happened to have stayed behind (no inheritance, as would have been normal) and any small allowance if paid to an unlikely dependent (only to one dependent in case there are more than one) is at the discretion of the appointed state custodian. The Israeli custodian has the power to liquidate businesses and annul business partnerships, to demolish buildings not authorized by the custodian, to sell or lease immovable property (through the Development Authority), and to rent buildings or allow cultivation of fertile land to a person (an Israeli Jew of course), with some income due to the custodian, but such that “his right shall have priority over any charge vested in another person theretofore.”

In one of the most incredulous sections (27), the law defines who could apply to be defined as “not an absentee”—only if that person left his residence “for fear that the enemies of Israel might cause him harm,” but excludes those who left “otherwise than by reason or for fear of military operations.” (In other words, it makes “not absentees” equivalent to Israelis who are not “absentee” anyway but beneficiaries from “absentees.”) Section 30 states that the “plea that a particular person is not an absentee … by reason only that he had no control over the causes for which he left his place of residence … shall not be heard” (presumably to apply to men who were not fighters, women and children, etc.). Thus, this “law” tries in every way to cover all the corners, to make sure that the original owners have no recourse to recover their rights under Israeli law. Israel creates such laws to say that what it is doing is legal, and to give its courts the tools to approve.

While this “law” was especially useful in the early years of the state, making possible expropriation of more than 6 million dunums of land, it is still being used today. The “law” is careful in defining “Palestinian citizens” (contrary to later Zionist denials that they exist), and in delineating for absenteeism the period 29 November 1947 to 19 May 1948 with the design to include the hundreds of thousands of properties lost in 1948. (“Present absentees” applied as well to more than 35,000 Palestinians who became Israeli citizens after 1948, and they or their descendants are still in that category.)

Since the illegal annexation of East Jerusalem, Israel has used the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law to confiscate properties from those classified by it as absentees although they are present. Technically absentees by Israeli definition, East Jerusalem residents were mostly exempt from this status in the Law and Administration Ordinance 5730-1970, section 3, thus considered “not absentee” only if they were physically present in Jerusalem on the day of annexation. However, that section excluded Palestinians who lived outside the municipal boundaries but owned land or property inside the city limits, or those who happened to be visiting outside the country. Occasionally after 1967 and after the 1980s, Israel and settler groups have found it expedient to apply the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law in places like Silwān and Sheikh Jarrah as well as in areas to the north of Beit Sahour, Beit Jala and Beit Lahm (Bethlehem) that were incorporated into the enlarged Jerusalem municipality.

As happened with Gilo in1970, 460 acres of land were expropriated in 1991 on Jabal Abu Ghneim south of Jerusalem to build a colony called Har Homa, which now has a population of more than 25,000 Israeli Jews. The residents of Beit Sahour, who owned the land, were thus declared “absentees” (since they were prevented from reaching it) and their lands seized without compensation or legal hearing. In addition to the plan within Greater Jerusalem, an objective was clearly stated that this expansion is intended to obstruct any future expansion of Beit Sahour and Bethlehem.

Another excuse used was that in the 1940s a Jewish group had purchased 32 acres, on the hill! The strategy is similar to some other locations such as the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem, Hebron, and “Neveh Ya‘akov” colony, where a contention of some pre-1948 ownership was used to take much more land to build huge colonies and establish enclaves.

The Abandoned Areas Ordinance was an immediate measure taken on 30 June 1948 (retroactive to 16 May) to define abandoned areas as “any area or place conquered by or surrendered to armed forces or deserted by all or part of its inhabitants, and which has been declared by order to be an abandoned area.” The Ordinance provided for “the expropriation and confiscation of movable and immovable property, within any abandoned area” and authorized the Israeli government to determine what would be done with this property.

The 1953 Land Acquisition Law was the second law enacted after the Absentees’ Property Law as another step to wrest land from Palestinians. This law immediately confiscated an additional 1.3 million dunums of Palestinian land, affecting 349 towns and villages, in addition to the “built-up areas” of about 68 villages. This “law” completed the process of formal transfer of ownership, until then, of expropriated lands from their Palestinian Arab owners to various Israeli state institutions, and permitted the Minister of Finance to transfer ownership to the Development Authority. The authority to expropriate also resides in the Planning and Construction Law of 1965, and in a number of other legislative acts such as the Water Law, the Antiquities Law, Construction and Evacuation legislation, and others.

Several other “laws” are used to acquire Palestinian land. One is the Prescription Law, 5718-1958 enacted in 1958 and amended in 1965, which essentially repealed provisions of the 1858 Ottoman Land Code, and which also reverses some British practices of that law. It changes the criteria for Miri lands, or arable land whose cultivators were tenants of the state but entitled to pass it on to their heirs, one of the most common types in Palestine, in order to facilitate Israel’s acquisition of such land. According to the Centre on Housing Rights Evictions (COHRE) and the Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights (BADIL), the Prescription Law is one of the most critical to understanding the legal underpinnings of Israel’s acquisition of Palestinian lands, both in the period after 1948 and in the West Bank after the occupation of 1967. Although not readily apparent in the language, in conjunction with other land laws, this law enabled Israel to acquire lands in areas where Palestinians still dominated the population and could lay claims to the land.

Another is a leftover from the British Mandate, the Land Ordinance (Acquisition for Public Purposes) of 1943, which remained active for Israel because of its usefulness in enabling land expropriation, particularly in Jerusalem. After enlarging the municipal border, Israel gradually issued scores of orders expropriating several additional square kilometers for “green areas” under the provisions of this old regulation. Declared as “public parks,” the acquisitions are in fact designed not for “conservation,” but rather to prevent Palestinian development, to isolate Palestinian areas, to ensure the contiguity of Jewish areas, and to build for Israel’s purposes. Until now, four “national parks” have been declared in East Jerusalem, including on privately- owned Palestinian land and land adjacent to Palestinian neighborhoods or villages, with plans for more “parks” under way.

Israel also amends to serve its purposes. On 10 February 2010, the Knesset passed an amendment to the 1943 Land Ordinance (Acquisition for Public Purposes), with the primary aim of confirming state ownership of land confiscated from Palestinians, even where the land had not been used to serve the purpose for which it was originally confiscated. The amendment was devised to circumvent an Israeli Supreme Court decision (in the Karsik case of 2001), whose precedent Palestinian Israelis were planning to use to retrieve property. This amendment gives the state the right not to use the confiscated land for the specific purpose for which it was confiscated. It further establishes that a citizen does not have the right to demand the return of the confiscated land in the event it has not been used for the purpose for which it was originally confiscated, if ownership of the land has been transferred to a third party or if more than 25 years have passed since its confiscation. The new amendment also expands the authority of the Minister of Finance to confiscate land for “public purposes.” It defines “public purposes” to include the establishment of new towns and expansion of existing ones. The law also allows the Minister of Finance to change the purpose of the confiscation and declare a new purpose if the initial purpose had not been realized.

Such pliability in legal application is clear in Israel’s continued use of the Defence (Emergency) Regulations enacted by the British in 1945, with some modifications (although the Zionists were vehement in their attack on these British regulations before 1948). The regulations included provisions against illegal immigration, establishing military tribunals to try civilians without granting the right of appeal, conducting sweeping searches and seizures, prohibiting publication of books and newspapers, demolishing houses, detaining individuals administratively for an indefinite period, sealing off particular territories, and imposing curfews. In 1948, Israel incorporated the Defense Regulations, pursuant to section 11 of the Government and Law Arrangements Ordinance, except for “changes resulting from establishment of the State or its authorities.”

There was debate in the Knesset in the early 1950 about repealing the Defense Regulations for their undemocratic practices, but they were never abolished because they served the military rule imposed on the Palestinian Arabs who had remained in Israel and became citizens. After cancellation of military rule, a Ministry of Justice committee was entrusted with drawing up proposals for repeal, but the occupation of 1967 brought a stop to this process, and resulted in the Emergency Regulations (Judea and Samaria, and the Gaza Strip – Jurisdiction in Offenses and Legal Aid), whereby it was decided the Regulations were in effect as part of the status before the occupation and thus still in effect. Israel has since used these regulations to punish residents, demolish hundreds of houses, deport and detain thousands of people, impose closures and curfews, and other measures. These Regulations were amended in 2007, mainly to exclude Gaza.

In one instance the Israeli system tried to liquidate claims that could be lodged by Palestinians who lost their property, such as in an amendment in 1973 called Absentees’ Property (Compensation). This amendment devised a ghostly arrangement according to which Palestinian Arabs in “unified” East Jerusalem could receive compensation for their property elsewhere on the basis of its value in 1947. While the properties of tens of thousands of Palestinians who had left the Western sector had been transferred to the Custodian of Absentee Property, there was only a very small percentage remaining in East Jerusalem, and the majority who were no longer residents of Israel were still not entitled to claim compensation. Jews, too, were compensated for their property in the eastern part of the city where public structures were built, but here the sum was calculated according to the 1968 value. This of course resulted not only in uneven legal application, whereby Jews can make their claim and Palestinians cannot make theirs, but also a measure that could for propaganda purposes say the “Arab refugee” problem is being solved, but limits the compensation to residents of Israel, patently not refugees. In effect it is an erasure of the larger claims by hundreds of thousands of the dispossessed, ending up being a take-it-forever law since Israel could declare ownership reverted to it after the set period was over.

Demographic Control and Residency Regulation

In June 1967, Israel held a census in the annexed area. Those who were present were given the status of “permanent resident” in Israel – a legal status accorded to foreign nationals wishing to reside in Israel. Yet unlike immigrants who freely choose to live in Israel and can return to their country of origin, the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem have no other home, no legal status in any other country, and did not choose to live in Israel. It is the State of Israel that occupied and annexed the land on which they live.

Permanent residency confers fewer rights than citizenship. It entitles the holder to live and work in Israel and to receive social benefits under the National Insurance Law, as well as health insurance. But permanent residents cannot participate in national elections – either as voters or as candidates – and cannot run for the office of mayor, although they are entitled to vote in local elections or run for the municipal council (although none have done so). And this residency can be lost.

The residency system imposes arduous requirements on Palestinians in order to maintain their status, with drastic consequences for those who don’t. If they happen to live outside the country for study or work more than seven years or if they take on another passport or take on residence in another country, or live outside the municipal boundaries, that automatically results in revocation of residency in Jerusalem. Some revocations have taken place for flimsier reasons, invoking the 1952 Law of Entry for anyone who does not maintain “a center of life” in Jerusalem (except Jews of course, who often shuttle back and forth from business and work abroad, and keep their apartments vacant in colonies). Jewish residents of Jerusalem who are Israeli citizens do not have to prove that they maintain a “center of life” in the city in order to safeguard their legal status, and many have dual citizenships.

Between the start of Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967 and 2017, Israel has revoked the status of more than 15,000 Palestinians from East Jerusalem, according to the Interior Ministry, which means they lost the right to live there along with benefits for which residents pay taxes. The Law of Entry authorizes arrest and deportation for those found without legal status. Without legal status, Palestinians cannot formally work, move freely, renew driver’s licenses, or obtain birth certificates for children, needed to register them in school. The discriminatory system pushes many Palestinians to leave their home city in what amounts to forcible transfers, a serious violation of international law.

Permanent residents are required to submit requests for “family reunification” for spouses who are not technically residents. Since 1967, Israel has maintained a strict policy on requests of East Jerusalem Palestinians for “reunification” with spouses from the West Bank, Gaza or other countries. In July 2003, the Knesset passed a law barring these spouses from receiving permanent residency, other than extreme exceptions. The law effectively denies Palestinian East Jerusalem residents the possibility of living with spouses from Gaza or from other parts of the West Bank, and denies their children permanent residency status.

More than 10,000 children born to such “mixed” marriages are being refused registration as another measure to control the city’s Palestinian population. Israeli policy in East Jerusalem is geared toward pressuring Palestinians to leave in order to shape a geographical and demographic alternate reality.

Residency revocation is employed as well as collective punishment for the entire extended family after an attack on Israelis by a member of the family. In Jabal el Mukabber after such an attack, the mother and 12 family members, including minors, received notices from the Ministry of Interior revoking their residency. The Interior Minister stated that “anyone conspiring, planning or considering a terrorist attack will know that his family will pay dearly for his actions.”

“Loyalty to Israel” has become a law for occupied Jerusalemites. It was first applied “illegally” in 2006 by the Interior Minister who revoked the residency of four members of Hamas elected to the Palestinian Authority’s legislative council. The case was stuck in court for over a decade. In early 2016 and before the Israeli courts ruled on the issue, Israel’s Interior Ministry again invoked this power to strip three 18 and 19-year-old Palestinians of their IDs for throwing stones.

In September 2017, the High Court of Justice held that the Interior Ministry did not have the statutory authority to strip East Jerusalem ID holders of their legal status, but postponed the application of the decision for six months to permit the Knesset to pass a bill to provide for the statutory authority. Now a new “law” has been enacted (in March 2018) to take away the residency ID of anyone if there’s a “breach of loyalty” to Israel—that is, requiring the occupied person who has been placed in limbo (not a citizen of any country) to have loyalty to the occupier. Israel has “unified” the two parts of Jerusalem, but wants to keep Palestinian Jerusalemites outside the formula and makes all efforts to diminish their number.

With the scarcity or absence of building permits, some Palestinians improve or build without permits, and thus there have been hundreds of demolitions. Illegal settlements, however, are multiplying while Jewish building is not demolished but protected. Since 1967, there have been more than 25,000 home demolitions in the West Bank and more than 2,000 in East Jerusalem. Studies have shown that the rate of demolition for permit violators in East Jerusalem is more than twice as high as for similar Jewish violators in West Jerusalem. According to Meir Margalit, the demolitions and associated measures are part of the broader context of colonial control over land and processes similar to those implemented by white settlers in settler colonial societies worldwide.

Right of Birth vs Law of Return

Many countries have avoided holding Israel accountable under international law for its practices. Instead, in some countries like the U.S., huge amounts of tax-exempt money continue to be collected to support Israel’s colonizing activities. With U.S. recognition of “Jerusalem” as Israel’s capital, permission has been granted to the occupying power to continue to Judaize the city with impunity. The unevenness in the application of justice is abundantly flagrant.

Israel and Zionist organizations have successfully obtained reparations for Jewish suffering in WW2, not only from Germany but from other countries. The World Jewish Restitution Organization has repossessed property that belonged to people of Jewish background, sometimes with sketchy documentation. Even unidentified bank accounts and such items as jewelry and art work have been recovered. This ought to be a precedent that, under normal moral standards, applies to Palestinians who lost their homes and properties in 1948, in 1967 and later.

Being born in a place is enough in several countries for one to earn citizenship, regardless where the parents come from or their status. In the U.S., for example, this applies to children of people on temporary student or visitor’s visas, and, as in the case of the DACA issue, even those who arrived illegally as minors may eventually have a path to citizenship.

Not so in Israel, or in Jerusalem. Any Jew not born in Palestine or Israel, upon arrival in Israel, has the right to citizenship under Israeli law, a right denied to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians born in the country before or after 1948. In Jerusalem, isolated from its natural rhythm by artificial barriers and colonies, children now born in it can go unrecognized and unregistered, while those already born in it are either not allowed into its compass or their official belonging to it is withdrawn arbitrarily and by force. Those Palestinians who remain in it as recognized residents, not citizens, are controlled in their rights and their future, their ability to develop constricted, and efforts continue to deplete their number.

This type of mentality and resultant policies would be made to stop in a normal world, as a perversion of law and any sense of truth. Adalah’s Discriminatory Laws Database lists over 65 Israeli laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens in Israel, Palestinian residents of other occupied territories and in Jerusalem on the basis of national belonging and of being non-Jews, whether explicit or indirect in their implementation in various aspects of life. And now we have further confirmation of the apartheidist nature of the state in the “Basic Law: Israel as the Nation State of the Jewish People,” enacted on July 19, 2018.

In view of all the above, it was particularly jarring and patently absurd to watch the gleeful faces of Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and billionaire Sheldon Adelson at the celebrations of the move of the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem. Fundamentalist preacher Robert Jeffress and other evangelicals spoke at the event and gave prayers, in effect reviving the old thinking that identified the U.S. national myth with biblical Israel as a justification for colonial expansion. Clearly, it reflected a dangerous alliance between rapacious Zionist colonization and blind evangelistic mania that harks back to the worst periods of colonization and surely negates the presumed spirituality and higher values “Jerusalem” is supposed to represent.

The history of Jerusalem has been so filled with imaginaries, investments, and inventions, which were generally somewhat benign, but are now exploited with dreadful designs and deceptions. It is an unusual situation that differs from other “holy” cities where the sacred is at least stabilized into mundane religiosity. The world must know that these “Holy Land” abuses are a parody of the holy.

By Donald Wagner

This issue of TheLink examines how, in order to subvert international law, human rights, and justice for all the parties to the conflict in the Holy Land, three “liberal” U.S. presidents and two mainstream Protestant theologians were influenced by domestic political considerations and a false theology of religious exceptionalism.

Woodrow Wilson, U.S. President, 1913 – 1921

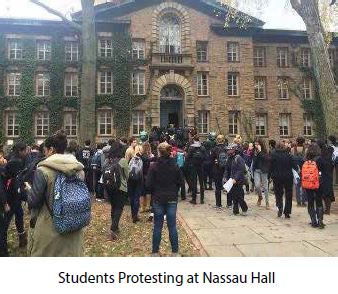

When the Princeton University student group Black Justice League assembled at historic Nassau Hall in mid-November, 2015, it demanded former President Woodrow Wilson’s name be removed from all campus buildings and programs due to his racist legacy.

When the protest moved inside President Christopher Eisgruber’s office, the students insisted that their demands be met in a timely fashion and submitted two additional demands: the university must institute cultural competency and anti-racism training for staff and faculty, and a cultural space must be provided for black students on the Princeton campus.

The Princeton incident should be seen in the context of similar campus and city-wide protests now underway across the United States, including the broad-based movement against police brutality in Chicago and other major cities. But the Princeton protest had a unique dimension as it focused on the legacy of a prominent leader who had been president of both Princeton University and the United States. The so-called “liberal legacy” of Woodrow Wilson’s impeccable image was suddenly brought under scrutiny and, indeed, it is a significantly tarnished legacy. Wilson was, without question, a notorious advocate of racial segregation. President Eisgruber acknowledged as much by stating: “I agree with you that Woodrow Wilson was a racist. I think we need to acknowledge that as a community and be honest about that.”

This strange case of President Wilson elicits yet another dimension of his racism and flawed decision-making: his betrayal of a just solution for the indigenous Palestinian Arab majority amidst the rise of the Zionist movement. When presented in the fall of 1917 with the British request to support a draft of the Balfour Declaration, which favored the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, Wilson had to decide between political pressure from the British and Zionists and pressure from his own State Department to continue advocating for his “Fourteen Points,” especially the guarantee of self-determination to majority populations in the Ottoman territories. Moreover, as a Presbyterian, he may have been influenced by his church’s inclination to be favorably disposed to the Zionist cause.

Wilson’s initial response was to postpone the decision. There was simply too much on his plate with the pressures of World War I, various domestic disputes, and promotion of his “Fourteen Points.” The British elevated the pressure on him through his friend, Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, a committed Zionist. Brandeis received a cable from Chaim Weizmann, leader of the World Zionist Organization, asking for the United States to support a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The British Parliament had not at that point adopted the Declaration, but Balfour believed support from the United States was crucial if it was to be passed by Parliament and eventually the Allied nations.

About a month after the Weizmann telegram to Brandeis, Balfour raised the stakes with a personal visit to Washington and a face to face meeting with Brandeis. He urged Brandeis to secure a favorable decision from Wilson as time was running out. When Brandeis followed up with Wilson he was told that a decision would need to be delayed as the State Department was concerned about the unpredictability of the War and the potential for negative consequences if the pro-Zionist Balfour Declaration were to be adopted.

On September 23, 1917, the British made an official request directly to President Wilson. Despite strong opposition from the State Department, Wilson approved the Declaration, but on the condition that the decision remain confidential. Nahum Goldman, later the leader of the World Zionist Organization, said: “If it had not been for Brandeis’ influence on Wilson, who in turn influenced the British Parliament’s decision and the Allies of that era, the Balfour Declaration would probably never have been issued.”

What was the role of religion in Wilson’s decision to embrace the Balfour Declaration? There is no clear statement from Wilson on this matter but it is worth considering that he was self-defined as “the son of the manse.” His father was a Presbyterian minister and Wilson was a student of the bible, a rather conservative student at that, which may have predisposed him to favor the Zionist narrative and its exclusive claim to the land of Palestine. Former C.I.A. analyst Kathleen Christison makes the case:

For Wilson, the notion of a Jewish return to Palestine seemed a natural fulfillment of biblical prophecies, and so influential U.S. Jewish colleagues found an interested listener when they spoke to Wilson about Zionism and the hope of founding a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Few people knew anything about Arab concerns or Arab aspirations; fewer still pressed the Arab case with Wilson or anyone else in government. Wilson himself, for all his knowledge of biblical Palestine, had no inkling of its Arab history or its thirteen centuries of Muslim influence. In the years when the first momentous decisions were being made in London and Washington about the fate of their homeland, the Palestinian Arabs had no place in the developing frame of reference. (Kathleen Christison, “Perceptions of Palestine,“ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001; 26)

Wilson’s now famous statement to Zionist Leader Rabbi Stephen Wise in 1916 seems to confirm Christison’s analysis: “To think that I, a son of the manse, should be able to help restore the Holy Land to its people.”

Wilson was very much a product of his southern heritage and his era happened to be one that was undergoing a resurgent racism as a reaction to the limited gains of Reconstruction. This period was known as the “Great Retreat,” or the “Nadir.” Historian James W. Loewen places Wilson in this context as the most racist president since Andrew Johnson. Loewen writes: “If blacks were doing the same tasks as whites, such as typing letters or sorting mail, they had to be fired or placed in separate rooms or behind screens. Wilson segregated the U.S. Navy, which had previously been de-segregated…His legacy was extensive: he effectively closed the Democratic Party to African-Americans for another two decades, and parts of the federal government stayed segregated into the 1950s and beyond.” (James W. Loewen, “Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism,” New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005; 41)

Loewen’s analysis of the “Nadir,” and the white reaction to Reconstruction points out that it was nation-wide, with several counties in states such as Illinois and Wisconsin returning to enforced systemic racism, including the humiliating “sundown towns,” where blacks were forced by local laws to vacate certain cities and towns by “sundown” or face imprisonment or brutal beatings. Wilson was clearly a product of the “Nadir” and racism may have played a significant role in his disregard for justice in the case of the “brown” Palestinian people, while favoring the white Zionists of Europe.