Introduction From The Editor

The Link has chronicled the connection between the term Apartheid and the Israeli Occupation for years, including in 2007 when Jimmy Carter’s book first made waves. While some weary at what they see as an endless debate over semantics, we reprise the topic as our 2022 opener given the mounting pile of evidence and the recent year’s developments (including a report Amnesty International just released as we went to press).

Through the clear-eyed lens of a seasoned journalist, we hope this issue of The Link will shine more light (and less heat) on a subject that we believe is anything but semantic. Our commitment remains to provide American readers with a better understanding of the Middle East, including the institutionalized racism that continues to afflict it in the 21st century.

To that end, The Link enthusiastically welcomes The Guardian’s Chris McGreal and his long and intimate acquaintance with the three sides of this triangle– Johannesburg, Jerusalem and Washing-ton. McGreal is a trusted interlocutor and consummate professional who draws on a wide range of fact and testimony in his reporting.

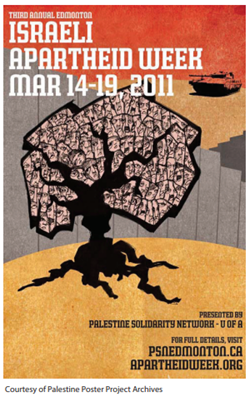

Among McGreal’s many references, we’re glad to be reminded of the Canadian initiative, “Israel-Apartheid Week”. Among many others, that effort is chronicled in detail by the Palestine Poster Project Archive, the world’s largest collection of Palestine- centered graphic arts; we are grateful for PPPA’s permission to sample from their archive for this edition. [PPPA is widely recognized for its role in preserving and celebrating the cultural heritage that is reflected in the over 15,000 posters they’ve archived since 1900. We look forward to sharing more from this treasure trove in future issues (www. PalestinePosterProject.org).

Along similar lines, we greatly appreciate Zapiro’s (South Africa’s acclaimed cartoonist/satirist) permission to publish his 2014 cartoon on this issue’s cover; we think it sums up the issue quite succinctly. (For those who don’t know his work, Zapiro’s pen is sharper and mightier than any number of swords. Treat yourself: https://www.zapiro.com/.)

At the close of this edition, we offer a brief remembrance of a former Board member, friend, and loyal supporter of AMEU, Henry C. Clifford, Jr. On page 15 of our PDF version John Mahoney shares his appreciation.

Lastly, a recent conversation with a longtime supporter in Chicago recalls a slogan that once echoed on Robben Island, South Africa’s infamous prison. ‘Each One Teach One’ underscored the importance of shared learning in our global quest to be better. One way our friend in Chicago has put that belief into practice over the years is by taking maximum advantage of our backpage offer, and endowing dozens of gift subscriptions to The Link. At $20 each, those gift subscriptions are one way AMEU extends its reach, farther and wider. So, if you haven’t done so recently, consider using that back page tearsheet and share us with a local library, a Congressperson, or a neighbor. We’ll send your gift recipient a one-year subscription to The Link, along with a copy of “Burning Issues”, our 440-page anthology of some of our best Link issues in the archives. To submit names and make payment on-line, go to our website, http://ameu.org/, and use the Donate button; be sure to let us know if you would prefer your gift to be anonymous.

Nicholas Griffin

Executive Director

Apartheid…Israel’s Inconvenient Truth

In 2006, Jimmy Carter published his bestselling book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, to wide acclaim and a vicious campaign to discredit the former US president.

Most of the criticism did not challenge Carter’s assessment that Israel’s actions in the occupied territories amounted to colonization and domination of the Palestinians, or his conclusion that it amounted to a system of South African-style apartheid. Instead, the former president’s critics put their efforts into questioning his motives in writing the book. The critics moved directly to smear the 39th American president as an anti-Semite.

The Anti-Defamation League called Carter a “bigot”. Pro-Israel pressure groups placed ads in The New York Times accusing him of facilitating those who “pursue Israel’s annihilation”. Others claimed he was “blinded by an anti-Israel animus”. Universities declined to let him speak and senior Democrats disavowed their former president’s views.

Never mind that it was Carter who brokered the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, a factor in the Nobel committee awarding him the 2002 peace prize. Or that Israeli politicians, including former cabinet ministers, said his assessment reflected what many Israelis thought. Carter’s crime was, as he himself recognized, to speak out on a subject about which open discussion had long been circumscribed in the US. “The many controversial issues concerning Palestine and the path to peace for Israel are intensely debated among Israelis and throughout other nations—but not in the United States,” Carter wrote in the Los Angeles Times, as the orchestrated backlash against him gained momentum.

“For the last 30 years, I have witnessed and experienced the severe restraints on any free and balanced discussion of the facts. This reluctance to criticize any policies of the Israeli government is because of the extraordinary lobbying efforts of the American-Israel Political Action Committee and the absence of any significant contrary voices. It would be almost politically suicidal for members of Congress to espouse a balanced position between Israel and Palestine, to suggest that Israel comply with international law or to speak in defense of justice or human rights for Palestinians.” [Ed: President Carter meant the American Israel Public Affairs Committee.]

Of all the issues, none was more sensitive and off-limits than suggesting Israel practiced a form of apartheid, with its implications of racism and associations to the extensive and intricate web of oppression created by white South Africa to subjugate the black majority. Many of Carter’s critics preferred to see Israel’s Jewish population as the victim of Arab aggression, not the oppressor of Palestinians, and to gloss over the role of occupation and Jewish settlements.

As if to prove Carter’s point, Nancy Pelosi, who was about to become speaker of the House of Representatives when his book was published, pointedly distanced the Democratic Party from the former president’s views. A New York Times article about the reaction to the book quoted Jewish and pro-Israel organizations attacking Carter’s motives, but did not include a single view from a Palestinian.

Fifteen years later, in the spring of 2021, Human Rights Watch (HRW) released a lengthy report accusing Israel of committing the crime of apartheid under two international conventions. The New York-based group’s detailed assessment, A Threshold Crossed, Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution, did not say much that wasn’t already known about longstanding Israeli policies to maintain “Jewish control” over the West Bank and East Jerusalem, and the three million Palestinians who live there.

“In pursuit of this goal, authorities have dispossessed, confined, forcibly separated, and subjugated Palestinians by virtue of their identity to varying degrees of intensity,” HRW said. “In certain areas, as described in this report, these deprivations are so severe that they amount to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.”

Palestinian rights groups, such as Al-Haq, have documented the same history of forced removals, house demolitions, land expropriations, and institutionalized discrimination for years. Israeli organizations have echoed those assessments of the impact of Jewish settlements and the separation barrier on Palestinians and their prospects for a viable independence.

Indeed, months before HRW published its report, Israel’s most prominent human rights group, B’Tselem, delivered its own indictment with a title that pulled no punches: A Regime of Jewish Supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea: This Is Apartheid.

In 2020, Yesh Din was the first major Israeli human rights organization to break the taboo and bluntly call the occupation by its name. “The conclusion of this legal opinion is that the crime against humanity of apartheid is being committed in the West Bank. The perpetrators are Israelis, and the victims are Palestinians,” the group said in a report.

In February 2022, Amnesty International added its voice with a report that said apartheid extended beyond the occupied Palestinian territories and to Israel itself. The report, Israel’s Apartheid against Palestinians: Cruel System of Domination and Crime against Humanity, said “whether they live in Gaza, East Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank, or Israel itself, Palestinians are treated as an inferior racial group and systematically deprived of their rights”.

But the HRW report nonetheless marked a milestone: after years of sidestepping, the US’s foremost human rights group had pinned the apartheid label to Israel’s actions. HRW said the decision was prompted, as the title of its report reflects, by a definitive change in the relationship between Israel and the occupied territories.

Omar Shakir, HRW’s Israel and Palestine director and author of the report, said Israel’s longest serving prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, stripped away any lingering illusions that the occupation is a temporary measure on the path to a Palestinian state.

“What has changed? The pace of building settlements and infrastructure connecting Israel proper to the settlements—I’m talking about roads, water networks, electricity—has rapidly increased,” he said. “In addition, the Israeli government has stopped playing the game of pretense. Netanyahu directly said in 2018, 2019, and 2020, that we in- tend to rule the West Bank in perpetuity, that Palestinians will remain our subjects. So the fig leaf for peace process was erased. Then in 2018, the Israeli government passed the nation-state law, which enshrined as a constitutional value that certain key rights are only reserved to Jewish people, that Israel was a state of the Jewish people, and not all the people that live there.”

But the path to HRW pinning the apartheid label to the occupation was not just a matter of identifying a shift in Israeli policies and actions. For years, pro-Israel pressure groups disparaged parallels between Israel and the white South African regime, which they argued were extreme and proceeded to discredit those who drew them.

In the US there was also a political cost. John Kerry, the then US secretary of state, was forced to apologize after he dared to warn in 2014 that Israel risked becoming an apartheid state if it didn’t end the occupation. Still, the apology was given in a manner which said that he regretted the political backlash not the thought. It was a view reportedly shared by President Barack Obama, who alluded to parallels between the Palestinian situation and the civil rights struggle in the US southern states.

Sarah Leah Whitson, the former director of HRW’s Middle East division who worked on the report, told me she spent years pushing for the group to describe Israeli actions as apartheid.

“Did it take over a decade to get there? Yeah, it did. Did it take much internal debate, to put it politely, and a great deal of hand wringing over how this would impact the organization not just in terms of funding, but in terms of our credibility and capacity to work on other countries? Were we going to be dismissed? Were we going to lose our standing? Were the Israel fanatics going to attack the organization so harshly that we would lose our footing? Those are legitimate considerations for any organization that works on 100 countries. Do you risk it all for Israel-Palestine? That was a genuinely held fear.” When the report was released, the worst of those fears were not realized. That in itself marked another milestone. There was a backlash against HRW from some of the usual quarters, including the Israeli government. “The mendacious apartheid slur is indicative of an organization that has been plagued for years by systemic anti-Israel bias,” Mark Regev, a senior adviser to Israel’s then prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, told The New York Times.

Those accusations were echoed by some pro-Israel groups. The Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations called the report “disgraceful” and said it was intended to “demonize, delegitimize and apply double standards to the State of Israel”—a formulation used by the former Israeli government minister Natan Sharansky to identify anti-Semitism.

The American Jewish Committee said the allegations of apartheid were “outrageous” and a “hatchet job” as part of HRW’s longstanding “anti-Israel campaign”. B’nai B’rith International, another pro-Israel group, fell back on a predictable line that Israel’s critics were “singling out” the Jewish state for criticism—a charge that implies anti-Semitic motives but holds little water when HRW is critical of governments on every continent.

But even beyond those whose business it is to defend Israel no matter what, there was less pushback than might have been expected. Relatively few Republican members of Congress joined the public condemnation of Human Rights Watch. The US State Department was restrained, simply saying that it “is not the view of this administration that Israel’s actions constitute apartheid” but without attempting to deny the facts laid out by HRW or discredit the group.

“It surprised all of us,” said Sari Bashi, an Israeli lawyer who worked on the report. “We thought there would be a much stronger reaction against it. I wouldn’t say that the conversation has shifted, I would say it’s shifting.”

The Palestinian political analyst Yousef Munayyer, former director of the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights, thought the reaction to the report more revealing than the report itself. “The fact that it didn’t have the same kind of pushback is a marker of the change that’s taking place,” he said.

That change is multifaceted and has been in the making for years. In part it’s a generational shift in perspective driven by a growing recognition that Israeli governments, particularly Net- anyahu’s, have used the—at best moribund—peace process as half-hearted and increasingly laughable cover for colonization of the West Bank.

Criticism of Israel has also accelerated recently, in the US in particular, in the wake of the social earthquake caused by the police murder of George Floyd in 2020, the subsequent surge in support for Black Lives Matter and a wider embrace of civil rights issues. With that has come a broader perception of the Palestinian cause as a struggle for social justice against an oppressive power and away from framing of the conflict as competing claims for the same territory.

That shift can also be seen within the US Jewish community, as some Jewish Americans, who once stayed silent for fear of being seen as disloyal to Israel, are increasingly willing to voice their concerns.

Apologists for Israeli government policies have long sought to portray parallels with apartheid as marginal and extreme and therefore unworthy of consideration and debate. But those comparisons have been drawn since the early years of the Jewish state’s foundation. As one of the architects of apartheid, South Africa’s prime minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, put it bluntly in 1961: “The Jews took Is from the Arabs after the Arabs had lived there for a thousand years. Israel, like South Africa, is an apartheid state.”

In 1976, Yitzhak Rabin, then in his first term as prime minister, warned against extended occupation and the fledgling Jewish settler movement dragging Israel into annexing the West Bank. “I don’t think it’s possible to contain over the long term, if we don’t want to get to apartheid, a million and a half (West Bank) Arabs inside a Jewish state,” he told an Israeli television journalist.

More than three decades later, two of Rabin’s successors as prime minister, Ehud Barak and Ehud Olmert, echoed his warning. “As long as in this territory west of the Jordan river there is only one political entity called Israel it is going to be either non-Jewish or non-democratic,” Barak said in 2010. “If this bloc of millions of Palestinians cannot vote, that will be an apartheid state.”

Three years earlier, after yet another round of failed peace talks in the US, Olmert cautioned that continued Israeli control of Palestinian territory would reshape the campaign for Palestinian rights. “If the day comes when the two-state solution collapses, and we face a South African-style struggle for equal voting rights, then, as soon as that happens, the state of Israel is finished,” he said.

Shulamit Aloni, only the second woman to serve as an Israeli cabinet minister after Golda Meir and leader of the opposition in the Israeli parliament in the late 1980s, once told me about meeting the South African prime minister, John Vorster, on his visit to Jerusalem in 1976. “Vorster was on a tour in the West Bank and he said that Israel does apartheid much better than he does with apartheid in South Africa. I heard him say it,” she said. In 2007, The Link republished an article Aloni wrote for Israel’s biggest selling newspaper Yediot Ahronot in which she defended Carter. “The US Jewish establishment’s onslaught on former President Jimmy Carter is based on him daring to tell the truth which is known to all: through its army, the government of Israel practices a brutal form of Apartheid in the territory it occupies,” she wrote.

A string of Israeli officials has agreed. Two decades ago, former attorney general Michael Ben-Yair wrote that Israel “established an apartheid regime in the occupied territories immediately following their capture” in 1967. Ami Ayalon, the former head of Israel’s Shin Bet intelligence service, has said his country already has ‘apartheid characteristics’.

Israel’s former ambassador to South Africa, Alon Liel, told me 15 years ago that his government practiced apartheid in the occupied territories and that the suffering of the Palestinians is as great as that of black South Africans under white rule. AB Yehoshua, one of Israel’s greatest living writers, joined the fray in 2020: “The cancer today is apartheid in the West Bank,” he told a conference. “This apartheid is digging more and more deeply into Israeli society and impacting Israel’s humanity.”

Some South Africans saw it too. The former archbishop of Cape Town, Desmond Tutu, who died in December, went further and said that Israeli violence against Palestinians—routine and largely invisible to the outside world, except when it flares to a full-on assault against Gaza over Hamas rocket barrages or suicide bombings—is worse than anything the black community suffered at the hands of the apartheid military. “I know firsthand that Israel has created an apartheid reality within its borders and through its occupation. The parallels to my own beloved South Africa are painfully stark indeed,” he said.

For all that, very little of this conversation was heard in the US for many years. Whatever backing there was in Washington for the old South Africa, few were prepared to defend it as more than a bulwark against communism. Its white Afrikaner rulers could only dream about the kind of bedrock support shown for Israel on Capitol Hill and at the White House, and the influence of lobbyists for the Jewish state.

As Carter noted, powerful pro-Israel organizations, led by the lobby group AIPAC, for many years confined political debate about Israel and used their influence to create largely unquestioning support for the Jewish state in Congress—to the point that the US delivers $3.8 billion a year in aid to Israel, with almost no scrutiny or conditions.

Mostly absent from this discussion were the Palestinians themselves who have long characterized the occupation as a form of apartheid and described it as a continuation of Israel’s expulsion and displacement of about 700,000 Palestinians from their homes in 1948, known as the Nakba.

One measure of apartheid is that the people whose fate is being decided are marginalized from the debate and only permitted to speak within parameters decided by others. In the US, discussion of Israel’s actions is frequently led by those who claim a close connection to the country because they are Jewish but often are not Israeli citizens, do not live there and frequently know far less about the situation than they claim. Some have a Disneyfied view of Israel rooted in its foundation myths.

One who does not is the American former editor of the solidly pro-Israel The New Republic, Peter Beinart, who used to be influential as a liberal Zionist and staunch defender of Israel who now favors a single country with equal rights for Israelis and Palestinian. Beinart has written that until recently “the mainstream American conversation about Israel-Palestine—the one you watch on cable television and read on the opinion pages—has been a conversation among political Zionists”, a conversation that excludes Palestinians.

Professor Maha Nasser of the University of Arizona found that of nearly 2,500 opinion articles about Palestinians in The New York Times over the past 50 years, less than two percent were written by Palestinians. The Washington Post was even worse. Nasser said that pretty much the only Palestinian with a voice in the US media was the late Edward Said, a professor at Columbia University. For all that, she noted that while Said’s criticisms of the Oslo accords appeared in newspapers around the world, The New York Times did not run a single column by him on that particular issue.

Israeli leaders could generally expect an easy ride from the US press. When Netanyahu appeared on CBS’s Face the Nation during the 2014 Gaza war, the program’s host, Bob Schieffer, led him through one sympathetic question after another before describing the Israeli prime minister’s justifications for the attack as “very understandable”. When Schieffer finally asked Netanyahu about the deaths of hundreds of Palestinian civilians, it was only to wonder if they presented a public relations problem in “the battle for world opinion”

Schieffer wrapped up by quoting prime minster Golda Meir’s line that Israelis can never forgive Arabs “for forcing us to kill their children”.

The belated but growing acceptance of the legitimacy of describing Israeli policies as a form of apartheid has come about in large part because a growing body of Zionists in the US and Israel, and human rights groups in both countries, have publicly embraced the description. But credible Palestinian human rights organizations have been making the comparison for years, and have largely been ignored or dismissed as partisan.

“It’s less about what they said and more about who was saying it,” said Munayyer, the former director of the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights. “Palestinians have been screaming this at the top of their lungs but that’s part of what apartheid is – the voices of those who are marginalized by the system are automatically discounted because the system exists. It’s frustrating to have to deal with that but it’s unfortunately part of the reality we find ourselves in.”

The grip of the Israel lobby and a circumspect press has been eroded by the rise of alternative sources of information in the US. Greater access to foreign television news stations, such as the BBC and Al Jazeera, alongside the rest of alternative news and social media sites have exposed Israeli actions to a much wider audience.

Access to scrutiny of Israel’s increasing belligerence and right-wing rhetoric alongside video of the bombing of apartment blocks in Gaza, the forced removal of Palestinian families from their homes in Jerusalem, and Jewish settler violence against Arabs, has played an important part in reshaping views of Israel.

“People can see for themselves what’s happening in a way they didn’t before,” said Whitson. “It’s made it harder, particularly in the United States, for the emotional defenders of Israel, who’ve had this mythology about Israel and the kibbutz and sowing the land and this sort of fantasy of what Israel’s like, confronted with the reality of what they see in front of their faces, and what everyone sees in front of their faces.”

Along with that has come a significant shift in conversation in the US – most recently driven by the impact of Black Lives Matter but also shaped by evolving views of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in universities.

During the Palestinian uprising of the early 2000s, the second intifada, I asked a senior Israeli foreign ministry official what he saw as the greatest challenge in maintaining the support of friendly foreign governments. Gideon Meir had been part of the team that negotiated Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, served in the embassy in London where he became friendly with a young Tony Blair before he was prime minister, and in later years went on to become ambassador to Italy. But his concern was not about the views of Israel’s Arab and European allies.

Meir said there was only one country Israel could rely on and that was the US. He thought that Washington’s support for the Jewish state would remain solid enough among an older generation of Americans and therefore the political class for a few years, but he worried about the long term consequences of rising criticism of Israel in the universities.

Meir saw that the narrative was shifting among American students away from the framing favored by pro-Israel lobby groups of the only democracy in the Middle East fighting for its existence against Arab hate and suicide bombers. Increasingly, discussion about Israel/Palestine on college campuses was cast in the language of civil rights and liberation movements.

Israel Apartheid Week was launched in Toronto in 2005 and rapidly spread to universities across North America and Europe. Its success at putting Palestine on the student agenda is reflected in the push back against the campaign, including attempts to ban it as anti-Semitic at some US and UK universities.

The generation that so worried Meir is now in its 30s and opinion polls show he was right to be concerned. Although twice as many Americans sympathise with Israel than the Palestinians, the gap has narrowed considerably in recent years. Polls show a majority of Democrats want Washington to pressure Israel to take the creating of a Palestinian state seriously.

That shift has in part been brought about by a change in how the conflict is viewed. The terrible images of the aftermath of Palestinian suicide bombings during the Second Intifada, which allowed then prime minister Ariel Sharon to cast Israel as a victim of the same brand of terrorism visited on the US on 9/11, are ancient history to most Americans born after about 1990.

Instead they were raised on the waves of Israeli destruction in Gaza when rockets, bombs and shells wiped out entire families, levelled schools and hospitals, and killed Palestinians in disproportionate numbers. The 2014 assault on Gaza, when Israel responded to Hamas rockets that killed three Israeli teenagers with airstrikes and ground incursions that killed more than 2,000 Palestinians, solidified the view of a militarized state unleashing destruction against a largely defenseless population.

As a result, Israel’s longstanding narrative of a small nation perpetually on guard against the surrounding foes – an image that remains powerful with an older generation that remembers the wars of 1967 and 1973 – is less effective by the year among Americans and Europeans who have seen the Jewish state only in a position of power and domination.

Similarly, Israel’s claim to be the only democracy in the Middle East, by trumpeting that its Arab citizens have the right to vote, was severely dented by the passing of the nation state law in 2018 which enshrined Jewish supremacy over those same Arab citizens.

Three years later, some of the sting was taken out of criticism of the HRW report by a backlash in Israeli Arab towns against attempts to forcibly remove Palestinian families from East Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. Even as pro-Israel groups proclaimed that the Jewish state respected equal rights for all of its citizens, Arab residents of Lod, a Tel Aviv suburb, were taking to the streets to protest against pervasive institutional discrimination. Videos of the protests swept social media as the demonstrations spread to other cities amid stone throwing and arson, and beatings of both Arabs and Jews.

“You had the events on the ground in May which just seemed to emphasise the point of all of the reports because you saw what was going on in Jerusalem, what was going on in Gaza, and also what was going on throughout all of Israel,” said Munayyer. “Events on the ground really validated the report.”

Very often, those events were seen through videos and reports produced by Palestinians and distributed on social media, bypassing the traditional gatekeepers in the US press. With them came commentary that characterized the forced removals from Sheikh Jarrah and broader state violence against Palestinians as a continuation of the expulsion of Arabs at the birth of Israel in 1948 – a narrative that connects with the increased focus on social justice.

The breaking of the taboo on comparisons with South Africa has helped drive the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign modelled on the hugely successful global boycott campaign run by the Anti-Apartheid Movement from the 1960s.

BDS was founded by Palestinian civil society groups in 2005, a year after the International Court of Justice declared that the West Bank wall and fence, which has the effect of confiscating Palestinian land, is a breach of international law. The movement has grown significantly on university campuses, and gained traction with some trade unions and political parties.

The campaign has some way to go to match the success of the Anti-Apartheid Movement as it became one of the great social causes of its age. By the mid-1980s, one in four Britons said they were boycotting South Africa. Mobilization against apartheid in US universities, churches and through local coalitions was instrumental in forcing businesses to pull out and, in a serious blow to the white regime, foreign banks to withdraw financing for the country’s loans.

But BDS is making a mark that worries Israel. The campaign has had some visible successes, including the recent decision by the ice cream maker Ben & Jerry to end sales in the settlements. It has pressured investors into breaking ties with companies doing business with Israel’s security establishment or in the settlements.

In echoes of the cultural boycott of South Africa, actors and film-makers have refused to play in Israel. Some called for the Eurovision Song Contest to be withdrawn from Tel Aviv in 2019, and the New Zealand singer Lorde cancelled a concert in the city four years ago after fans urged her to join the artistic boycott of Israel.

BDS is also pressuring soccer’s governing body, FIFA, to expel Israel, so far without success. But Argentina cancelled a World Cup warm-up match with Israel after the players voted to boycott the game. The appearance of Palestinian flags at English Premier League matches suggests there is support for such action.

Although Israel disparages BDS as a fringe campaign, it’s clearly worried about its potential to build support, particularly among Europeans. An effective boycott could cost Israel billions of dollars a year. In 2015, the Washington-based Rand Corporation estimated that a sustained BDS campaign could reduce the Israeli GDP by 2 percent.

But BDS faces far more effective resistance than the Anti-Apartheid Movement ever did. Israel and its supporters have sought to head off the boycott movement before it gains greater momentum with laws recently promulgated in 32 out of 50 state legislatures to discourage and explicitly penalize support for BDS.

At the same time as a younger generation of Americans is reframing the conflict away from non-existent peace negotiations and toward civil rights, views of Israel have been shifting within America’s Jewish community. A survey of Jewish voters in the US last year (2021) found that 25% agreed that “Israel is an apartheid state” while a similar number disagreed with the statement but said it is not anti-Semitic to make the claim. In the poll by the Jewish Electorate Institute, 34% agreed that “Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is similar to racism in the United States”.

A Pew survey in May found that a younger generation of American Jews was less willing than its elders to make excuses for the Israeli government and more prepared to back BDS.

In the spring of 2021, as Gaza once again came under assault, nearly 100 rabbinic and other religious students at leading American Jewish colleges regarded as a crucible of future community leaders signed a letter decrying a double standard over standing up to racial injustice.

“This year, American Jews have been part of a racial reckoning in our community. Our institutions have been reflecting and asking, ‘How are we complicit with racial violence?’ Jewish communities, large and small, have had teach-ins and workshops, held vigils, and commissioned studies. And yet, so many of those same institutions are silent when abuse of power and racist violence erupts in Israel and Palestine,” the letter said.

The students lamented a tendency to focus on the long history of persecution of Jews while ignoring the realities of Israeli Jewish power and the responsibilities that come with it.

“Our political advocacy too often puts forth a narrative of victimization, but supports violent suppression of human rights and enables apartheid in the Palestinian territories, and the threat of annexation,” the letter said.

Shifting perspectives on Israel in the US are matched, and to some degree influenced by, a greater willingness by some in the Jewish state to face reality. Yesh Din was the first major Israeli human rights organization to break the taboo when in 2020 it described the occupation as apartheid and therefore a crime against humanity. “The crime is committed because the Israeli occupation is no “ordinary” occupation regime (or a regime of domination and oppression), but one that comes with a gargantuan colonization project that has created a community of citizens of the occupying power in the occupied territory. The crime is committed because, in addition to colonizing the occupied territory, the occupying power has also gone to great lengths to cement its domination over the occupied residents and ensure their inferior status,” its report said.

Yesh Din dismantled a core defense brandished by Israeli governments to influence American public opinion in particular by claiming that the occupation is not a permanent condition and will end when a deal on two states is reached. The rights group said that claim falls apart in the face of clear evidence that Israel’s policies in the West Bank are designed to cement domination of the Palestinians and the supremacy of Jewish settlers.

The author of the Yesh Din paper was the renowned Israeli human rights lawyer, Michael Sfard. By his own account, he spent years rejecting parallels with apartheid. But in 2021 Sfard wrote in The Guardian that he changed his mind in large part because his understanding of the relationship between Israel and the occupied territories shifted.

Sfard said that like many Israelis he bought into the idea of two entities. There was Israel, the imperfect democracy that discriminated against its Arab minority but then minorities in many democratic countries face discrimination. And then there was the occupation of Palestinian land which Sfard, in common with most of his compatriots, excused as a temporary condition. In the end though, the intent of “Israel’s colossal colonization project in the West Bank” had become undeniable: “It is occupation, obviously, but not only occupation.” He said he came to realize that the governing principle of the West Bank was “Jewish supremacy and Palestinian subjugation”.

Few can say they were not forewarned about the direction of travel under Netanyahu, who was prime minister for a total of 15 years. He opposed the Oslo Accords even before they were signed in 1993 and spent the next three decades subverting them, even if at times he paid lip service to two states to keep the illusion alive and stave off American diplomatic pressure.

Netanyahu did as much as any leading politician to create the climate in which an assassin’s bullet killed the author of the Oslo deal, Yitzhak Rabin, in 1995. Once he became prime minister for the first time less than a year later, Netanyahu set about finishing off what the assassin had started – the solidification of Jewish domination of the Palestinians in the occupied territories and within Israel’s own recognized borders.

Danny Danon, Israel’s recent ambassador to the UN and former chair of Netanyahu’s Likud party, openly opposes a Palestinian state and once told me that the then prime minister didn’t believe in it either. “I want the majority of the land with the minimum amount of Palestinians,” Danon told me in 2012.

Netanyahu threw his support behind the change to Israel’s basic law, in effect its constitution, that defined the county as ‘the nation state of one people only – the Jewish people – and of no other people’. His powerful right-wing economy minister, Naftali Bennett, backed the amendment by saying that Israel should have ‘zero tolerance’ for the aspirations of the Arab population. “I will do everything in my power to make sure [the Palestinians] never get a state,” he told The New Yorker in 2013.

Bennett is now Israel’s prime minister. His ultranationalist finance minister, Avigdor Lieberman, advocates stripping his country’s Arab population of Israeli citizenship. Bennett’s close political ally and interior minister, Ayelet Shaked, was an architect of the nation state law and pushed for effective annexation of parts of the West Bank.

Netanyahu continued to pay lip service to a negotiated two-state solution as a diplomatic fig leaf for US support for Israel. But the reality was hard to ignore for Daniel Seidemann, an Israeli lawyer, who has spent decades exposing the iniquities of Israeli rule in occupied East Jerusalem most recently through an NGO he founded, Terrestrial Jerusalem.

During the 2000s, whenever I asked him about parallels with apartheid, Seidemann resisted them. Like a lot of Israelis, Seidemann told himself the occupation came about through self-defense, and was temporary. It would end when agreement was reached to create a Palestinian state.

Then in May 2020 Seidemann retweeted a photograph of a group of Israeli officials sitting around a map discussing which parts of the West Bank to annex. He wrote, “For many years I resisted using the term “apartheid” in the context of occupation. I regret having to use it now, but there is no choice but to do so.”

Seidemann told me that he long sidestepped the comparison because he thought it was more frequently used for polemical attacks on Israel than to illuminate the realities of the oppression of Palestinians. He still has reservations. He remains convinced that the occupation is not driven by attitudes of racial superiority even though he acknowledges there is systematic racism.

“Having said that, and having bristled for a long period of time, I have no alternative but to increasingly not only concede but to use the apartheid paradigm in explaining what’s happening, particularly in the West Bank and East Jerusalem,” he said.

“Part of what has changed is that the occupation isn’t temporary. Occupation is being perpetuated. When occupation becomes permanent, and you have one geographical place with laws for one and laws for another, the comfort zone between that situation and apartheid narrows dangerously. We now have a situation which not only exists but by policy, by design, is being perpetuated; that within one geographical space there are those with political rights and those without them. That is not only disturbing, it raises the specter of apartheid.”

“There is no status quo because occupation requires increasingly repressive and nationalistic measures in order to sustain itself. Israel engages in policies which were unthinkable 10 years ago.”

Seidemann’s thinking on the part played by racism has also shifted. Israeli cabinet ministers now openly talk of ethnic cleansing and use racist terms in a way they were sensitive to two decades ago.

“Racism is becoming more of a factor in this conflict because so much of occupation is associated with our equivalent of a Trumpian right. We have our own version of white supremacy. I don’t think that informs everything but it’s certainly part of it. All of these things add up to, ‘How can you avoid the analogy?’” said Seidemann.

Yossi Sarid is another among a number of former Israeli cabinet ministers who have drawn the apartheid parallel. “What acts like apartheid, is run like apartheid and harasses like apartheid, is not a duck – it is apartheid,” the former education minister said in 2008. “It is entirely clear why the word apartheid terrifies us so. What should frighten us, however, is not the description of reality, but reality itself.” Still, it is the use of the word that continues to terrify Israeli officials, and for good reason.

Israel’s foreign minister, Yair Lapid, in assessing the diplomatic challenges he faces in 2022, warned of the “real threat” that international organizations, including the UN, will formally accuse it of practicing apartheid “with potential for significant damage. We think that in the coming year, there will be debate that is unprecedented in its venom and in its radioactivity around the words ‘Israel is an apartheid state,” he told a press briefing. “There is a real danger that a UN body will say Israel is an apartheid regime.”

Israel is facing twin investigations by the UN Human Rights Council and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Lapid said he expects one of them to call Israel an apartheid state when they issue reports later this year. The Palestinians have also asked the International Court of Justice in The Hague to rule that Israel practices apartheid and that its policies are racist. Lapid warned that the accusations of apartheid, and the diplomatic pressure they bring, are only likely to strengthen in the absence of meaningful negotiations to bring about a Palestinian state.

But Israel’s concern goes beyond the diplomatic and political. Human Rights Watch astutely avoided making direct comparisons with South Africa and instead framed its report around two international legal definitions of the crime of apartheid. The 1973 apartheid convention defines apartheid as a crime against humanity when it involves “inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them”

The 1998 Rome statute of the International Criminal Court defines apartheid as inhumane acts “committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime.” HRW has noted that its report does not call Israel an “apartheid state” because it does not have a meaning under international law any more than the term “genocide state”. Instead the group said individuals are responsible for committing the crime of apartheid as part of state policy.

Last year (2021), the then ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, announced she would proceed with an investigation of alleged war crimes in the Palestinian territories since 2014. The opening of a full investigation followed five years of preliminary examination by the prosecutor’s office after which Bensouda said she was satisfied that “there was a reasonable basis to believe that war crimes have been or are being committed in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip”.

The prosecutor’s office said it believed the Israeli military committed war crimes in its 2014 assault on Gaza through “disproportionate attacks” and “willful killing”. The office said it also found evidence to justify investigating Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups for war crimes including “intentionally directing attacks against civilians”, using human shields, and killings and torture.

A second part to the investigation is, perhaps, far more threatening. The ICC prosecutor’s office said there is evidence that the decades-long settlement enterprise is a war crime in breach of the ban on transferring civilian populations from the occupying power into the occupied territories. Both the Geneva Conventions and the ICC’s own statute ban the practice because, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross, Germany used it during the Second World War to “colonize” territories it occupied.

Accusations of crimes committed in the heat of battle can perhaps be explained away as the result of urgent decision making, bad intelligence and military necessity. But the move of nearly 400,000 Israeli citizens into more than 120 Jewish settlements in the West Bank– leaving aside occupied East Jerusalem– is a long-term project of successive governments that has involved extensive planning and thousands of officials. In addition, about 300,000 Israelis live in a dozen settlements inside East Jerusalem. The settlement project required land seizures, expropriation of resources such as water, and the forced removal of Palestinians from their homes, installing 700,000 settlers on occupied territory.

Although the ICC investigation will focus only on Israeli actions since 2014, the continued expansion and administration of the settlements involves an array of government departments as well as the military. Politicians setting policy, officials implementing it and members of the army imposing military law on the Palestinians in support of the settlers potentially face indictment. That could expose them to arrest and trial at The Hague if they travel to Europe or other parts of the world that are signatories to the ICC statute.

Israel would also face the challenge of having its entire settlement enterprise declared a war crime which would strengthen the hand of those arguing for international sanctions.

The ICC investigation alarms Israel’s leaders because the US cannot simply wield a veto as it does at the UN Security Council. Still, the probe hangs in the balance following the appointment of a new prosecutor, the British lawyer Karim Khan. He has not commented on whether he will proceed with it but Israel has taken heart from Khan’s decision to “deprioritize” a probe into the actions of US forces in Afghanistan.

The Israeli government has also sought to hinder investigation and exposure of its policies by going after human rights groups. In 2019 it expelled Omar Shakir, who had been based in Jerusalem for HRW, claiming he supported BDS. In October 2021, Israel designated six Palestinian civil society groups as terrorist organizations and banned them in a move widely interpreted as an attempt to suppress criticism and cut off foreign financial support. They included Al-Haq, one of the most respected Palestinian human rights groups. Israel has repeatedly failed to provide much promised evidence to back up its claim that the organizations were linked to terrorism.

For all of the pressure on Israel, and the shifting attitudes in the US, support for the Jewish state in Washington remains solid if not unchallenged. After the ICC launched its probe, a group of US Senators signed a letter urging the White House to try and block “politically motivated investigations” of Israel. The Senators described the occupied territories as “disputed”, said the ICC had no jurisdiction and claimed that the court’s involvement “would further hinder the path to peace”. Two-thirds of US Senators signed the letter including Kamala Harris, now the US Vice President.

That consensus has held on issues such as moving the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem under President Donald Trump, and maintaining Israel as the largest recipient of American aid and with no strings attached.

HRW’s Sarah Whitson said fractures are appearing in the Washington consensus but there is little sign they will bring about a dramatic shift in policy any time soon. “While the public narrative has shifted, while it’s clear from multiple surveys that increasing numbers of Americans see Israel as an apartheid state and don’t want the United States to provide military support, and they see Israel as the primary belligerent actor, there is such a massive disconnect between the shift in the public, even the shift in the [foreign policy] ‘blob’, and US government policies,” she said. “What’s been the most difficult, therapy-inducing, thing for some of those people who committed their lives to the Oslo process and a two-state solution is to come to terms with the reality that that’s completely failed. And not only has it failed, but that the apartheid has become more entrenched. But you have a long standing feature where those policymakers closest to the situation in many cases know how screwed up it is but will not shift their policies and positions.”

Still, there was real damage done by Netanyahu who played a part in fracturing the bipartisan consensus on Israel by breaking the longstanding Israeli dictum of always keeping the White House onside. He did not hide his hostility to Obama, treating him with a public contempt that would have been unthinkable by an Israeli leader toward an American president in years past. Netanyahu publicly aligned with the Republican leadership in Congress in opposition to the US and European deal with Iran to halt its nuclear weapons research, and after Obama pressured the Israeli leader to take Palestinian aspirations seriously. Then the Israeli leader openly sided with Trump.

Netanyahu’s embrace of Trump’s peace plan in January 2020, cooked up without Palestinian input, provided further evidence of the Israeli leader’s thirst for land over a negotiated agreement with the Palestinians. The plan was widely denounced, including by some leading Democrats, as a smokescreen for annexation by Israel of significant parts of the West Bank which would create a series of Palestinian enclaves reminiscent of the patchwork of bantustans across South Africa. Netanyahu praised it as “the deal of the century” and announced plans to immediately annex the Jordan Valley and Jewish settlements, although he was quickly forced to backtrack by an embarrassed White House.

The fracturing of the bipartisan consensus eased the way for three Democratic members of Congress – Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez – to accuse Israel of being an apartheid state and to back the boycott movement. Senior Democrats were unhappy with the congresswomen but also felt obliged to speak up on behalf of Tlaib, who is of Palestinian descent, and Omar after they were barred from visiting Israel in 2019 after Trump appealed for them to be kept out.

Tlaib used the incident to tie Israeli policies to Trump. “Racism and the politics of hate is thriving in Israel and the American people should fear what this will mean for the relationship between our two nations. If you truly believe in democracy, then the close alignment of Netanyahu with Trump’s hate agenda must prompt a re-evaluation of our unwavering support for the State of Israel,” Tlaib said in 2021.

For all the animosity, Obama agreed to a deal that increased US aid to Israel to $38 billion over 10 years. Nonetheless, a debate has emerged in Washington about the scale of US aid to Israel with attempts by some members of Congress to set conditions, including that the money cannot be used to further Israel’s annexation of Palestinian territory or fund the destruction of Palestinian homes.

The scale of the challenge in shifting policy was demonstrated by the pro-Israel lobby’s mobilization of more than 300 Representatives and Senators to sign a letter backing the continuation of financial support for Israel without conditions. A solid majority of Democrats in Congress also backed a resolution condemning the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

Still, the Israelis remain worried about the direction of the debate, including increased framing of the occupation as apartheid. The director general of its foreign ministry, Alon Ushpiz, earlier this year said that protecting bipartisan support for Israel in the US is a primary goal for 2022.

Seidemann, who travelled to Washington to gauge US policy on Israel in late 2021, said that’s a reflection of Bennett’s concern about whether the Jewish state will be able to count on America having its back. “It’s because of great concern at losing the younger generation, losing the Democratic Party,” he said. “The sands are shifting in the United States, in the Congress, in public opinion, and in the American Jewish community, and the apartheid discourse is part of it. There is a center but that center is not going to hold.”