Catalog of all Link issues Since 1968

The Link archive constitutes a body of informed commentary, fact, and anecdotal evidence valuable for writers, researchers, and historians.

In his Link issue of September-October 2017, Thomas Suarez begins his article “The Cult of the Zionists” with these words: “In the late 1800s, after centuries in which bigots strove to keep Jews as a race apart, a new movement sought to institutionalize this tribalism by corralling all Jews into a single vast ghetto on other peoples’ land.”

More recently, in his January-March 2021 Link “The Decolonization of Palestine,” Jeff Halper cites a position paper issued by Jewish Voice for Peace, now one of the largest Jewish organizations in the United States; it reads: “We unequivocally oppose Zionism because it… is a settler-colonial movement, establishing an apartheid state where Jews have more rights than others.”

Many of our Link issues —and all 54 volumes are on our website www.ameu.com — are based on books, as were Suarez’s and Halper’s. But others, such as Audeh Rantisi’s, are first-hand accounts that can only be found in AMEU’s Link Archive. I have singled out a few of these bound witnesses that unmask the cruel face of Zionism.

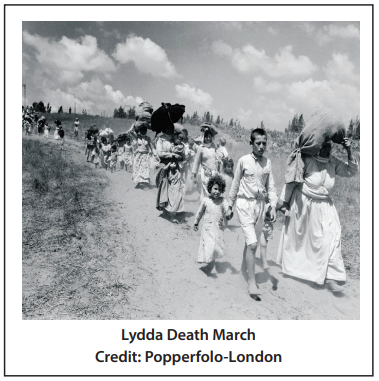

“The Lydda Death March” by Audeh Rantisi and Charles Amash

Volume 33, Issue 3, July August 2000

He was 11 when they came. It was mid-July, and hot. Three soldiers banged on the door and, in English, ordered them out. His family was Christian, and with hundreds of other Christians living in town, they headed to St. George’s Church.

They never made it. At a turn in the road just before the church, the soldiers ordered the confused villagers, now including Muslims, down a road that ended at a narrow gate that led to the mountains.

About a mile outside the gate they came to a vegetable farm, its entrance framed by a large gate, atop of which sat soldiers with machine guns firing over their heads, prodding them on through the gate. Audeh Rantisi did not know it at the time, but Lydda’s death march had begun.

What happened next was recorded by him in our July-August 2000 issue of The Link.

Inside the gate, soldiers ordered everyone to throw their valuables onto a blanket they had placed on the ground, including money, jewelry, wristwatches, pens, even wedding rings. When Amin Hanhan, married for only six weeks refused, one of the soldiers lifted his rifle and shot him. “Go to Abdullah,” the soldiers shouted, meaning the Palestinian territory under Jordanian control, a march of some 25 to 30 miles over rough terrain.

In the early hours of day two, soldiers on horseback came riding at them screaming for the 4,000 mostly women and children to get moving.

By day three, many had staggered and fallen by the wayside, either dead or dying in the scorching heat. Scores of pregnant women miscarried, their babies left for jackals to eat. Audeh can still see one infant beside the road sucking the breast of its dead mother. The survivors trudged on in the shadeless heat tormented by thirst to the point that some drank their own urine.

By day four, Audeh’s family arrived in Ramallah with only the clothes on their back. Their life as refugees had begun.

Included in this issue is the eye-witness account of the death march by Charles Amash, then 16, who confirms much of Rantisi’s account.

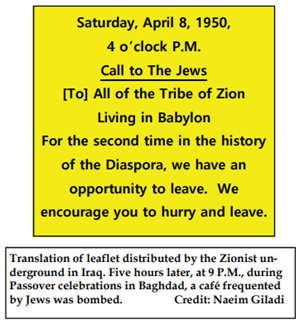

“The Jews of Iraq” by Naeim Giladi

Volume 31, Issue 2, April-May, 1998

The expulsion of families from Lydda was repeated in over 950 Palestinian towns and villages, resulting in some 800,000 refugees. This also left thousands of acres of cultivated land unattended. Zionist leaders were faced with two problems: one, to make certain the Palestinians did not return to their ancestral land and, two, to get Jewish laborers to take over the cultivation. Naeim Giladi knew the answer to both problems, being himself part of the answer.

A New York City rabbi first told me of Naeim who, by 1997, was living with his family in Whitestone, New York. I phoned him to arrange an interview and he graciously invited me, along with Link staff volunteers Jane Adas and Bob Norberg, to visit him at his home.

When we arrived we were anxious to do the interview, but Naeim insisted we have a lunch specially prepared by his wife. “It is our Arab custom,” he said, laying his out-stretched hand over his heart, “My wife and I speak Arabic at home.” When we did do the interview — following dessert and Arabic coffee — we thanked him for his family’s hospitality and for sharing his extraordinary life story: his membership in the Zionist underground in Iraq; his imprisonment and escape from the military camp of Abu-Ghraib; his experience as an “Oriental” Jew in the new state of Israel and his life in America.

As for discouraging Palestinian farmers from returning to their farms, Naeim would learn upon arrival in Israel of the state’s use of bacteriological warfare: In 1948, after Zionist forces emptied Palestinian villages of their populations, they poisoned the water wells to ensure their owners could not return . Naeim cites Uri Mileshtin, an official historian for the Israeli Defense Forces, who reported that Moshe Dayan, a division commander at the time, gave orders in 1948 to remove Arabs from their villages, bulldoze their homes, and render their water unusable by emptying cans of typhus and dysentery bacteria into the wells.

And as for finding Jewish workers to till the stolen soil, Zionists looked to Jews from Arab countries. The problem was how to convince them to leave their homeland; the answer: Terrorize them.

Some 125,000 Jews left Iraq for Israel in the late 1940s into 1952, most because they had been put into a panic by what Naeim later would learn were Zionist bombings of Jewish businesses and synagogues, followed by leaflets urging the frightened Jews to leave for Israel. Naeim, then a teenager, bought the lie and moved.

Once in Israel he was sent to al-Majdal (later renamed Ashkelon), a Palestinian town some 9 miles from Gaza. Here he was charged with forcing the indigenous inhabitants out of Israel into Gaza, then under Egyptian control, thus making it possible for Israel to establish its farmers’ city, now worked by “Oriental” Jews. It was an order he refused to obey.

Naeim married, had children, and continued to challenge the state’s ethnic policies. Then, when his son reached the age when he had to enlist in the Israeli army, Naeim took his family to America. He could have opted for dual U.S.-Israeli citizenship. He said no, he no longer wanted Israeli citizenship.

When we met with him in Whitestone, he was working as a night watchman and, unable to find a publisher willing to print his eye-witness account of Zionist atrocities. He eventually self published his book under the title Ben-Gurion’s Scandals. See Wikipedia, which also notes his Link article. Naeim died in 2010.

“The End of Poetry” by Ron Kelley

Volume 31, Issue 4, September-October, 1998

Early in 1998, I received a phone call from a cable TV producer in Manhattan. He asked if I’d like to see a documentary on the Bedouin of Israel. It’s rather extraordinary, he said.

The day after viewing Ron Kelley’s documentary, I phoned him at his home in Michigan and invited him to tell his story to our Link readers. He agreed in the hope that “the article can draw a little attention to the problem at hand.”

The problem at hand, it turned out, was the ravaging of a people and their way of life.

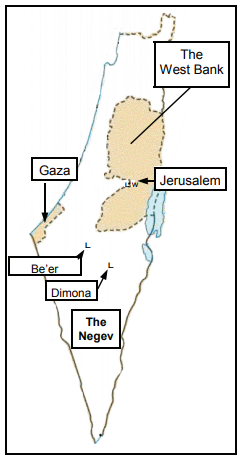

Kelley, then 47, a professional photographer with a degree in anthropology, first encountered the Bedouin in 1992 as a Fulbright scholar at Ben Gurion University in Be’er Sheva, Israel. What he saw there — the uprooting of a desert people — convinced him to bring a Hi-8 video camera into Israel and to embark on a clandestine project beyond his Fulbright one. When he returned to the States he had 120 hours of surreptitiously recorded videotape on which he spent $20,000 and countless hours turning it into a documentary on the Bedouin to show to U.S. networks. But nobody cared: not PBS, not ABC, not an “Arab-Jewish peace” foundation, and surprisingly, not many Arab and Muslim Americans whom he contacted.

What does the documentary reveal? It notes that, In 1948, the new Zionist state of Israel made the audacious claim that ALL the Negev desert was Jewish owned. The problem then for Israel was what to do with the Bedouin who called the Negev home? The short-term solution, it turned out, was to move as many as possible en masse to a reservation area in the northeastern Negev, where they were isolated under military rule until 1966, unable to leave the area without special passes. Nor were they permitted to buy land in the reservation as only Jews could own the land. Some tried to regain their desert homes in court but, as Kelley notes, of the 3,000 lawsuits filed by the Bedouin over a period of two decades, not one Bedouin had ever won a land claim.

Israel’s long-term solution was centered on seven governmentally created “industrial” towns, places segregated by law for Arabs only. Yet, even here, the land — considered part of the “Jewish People’s” perpetual inheritance — cannot be owned outright by the Bedouin, who can only lease plots for specified periods of time.

While Kelley was filming, approximately half of the 90,000 Bedouin in the Negev had been corralled in the government sanctioned reservations. The other half lived in the desert, where they had to contend with the Green Patrol, an independent paramilitary police unit whose major function was to harass and persecute the indigenous Bedouin. This, as Kelley documents, includes the ravaging of their homes, destruction of their crops, killing of their livestock, and the beating of men, women, and children.

AMEU made an arrangement with Ron to distribute his 2-hour long video-cassette “The Bedouin of Israel,” at a cost of $30 each. Not sure how many we would sell, we decided to buy them in lots of 20. When — and if — we ran out of the first lot, Ron gave us the phone number of his mother, who would run off another lot. To the best of my recollection we sold well over 100 cassettes, including some to human rights organizations. Then, one day, when we phoned to reorder another 20 copies, the number was no longer in service. It was the last we ever heard from Ron or his mother. And, anticipating a resupply of VCRs, we had sold our last one, and were left without a single copy of the video documentary. Only his Link article survives.

“Epiphany at Beit Jala” by Donald Neff

Volume 28, Issue 5, December 1995

Donald Neff was a seasoned reporter when, in 1975, he went to Israel as Time magazine’s Jerusalem Bureau Chief. And, like most Americans, he came as an unwitting Zionist, who believed that the Jews deserved a secure state of their own, as the Nazi Holocaust had proved, and it followed that Israelis had a right to look out for their own safety.

It was a preconception that would be challenged in multiple ways: the way most Israeli Jews failed to see the degradation imposed upon Palestinians by Israeli rule; the charming young Israeli woman who had lost her home in Germany and now lived comfortably in a home that once belonged to a Palestinian family; the 1975 U. N. General Assembly resolution calling Zionism a form of racism and racial discrimination; the 1976 Koenig Report, co-authored by Israel Koenig, Northern District Commissioner of the Ministry of Interior, that outlined how Israel could rid itself of some of its Palestinian citizens; the 1977 publication by The London Sunday Times of a major expose about torture of Palestinian prisoners by Israeli security officials.

But Donald Neff’s final revelation — his epiphany — came in March 1978. These are his own words from his Link article:

It began with a telephone call from a freelance reporter, a courageous American…close to the Palestinian lawyer Ramonda Tawil. She reported she had heard reports that Israeli troops had conducted a cruel campaign throughout the West Bank against Palestinian youth. Many Palestinians had suffered broken bones, others had been beaten and some had had their heads shaved. Some of the victims were in Beit Jala hospital.

When I repeated the report to my staff, all of them Israelis, they reacted with horror and indignation. The whole group, a secretary, a teletype operator, two stringers, a photographer, and two other correspondents, cast doubt on the story. They all declared it was unthinkable because “that is what was done to us in the Holocaust.”

About this time one of my best friends, Freddie Weisgal, stopped by. He was the nephew of one of Zionism’s important theoreticians, Meyer Weisgal, and a former human rights fighter in the United State before moving to Israel after the 1967 war… He said something like, “Aw, come on, Don, you know Jews wouldn’t do anything like that.” He was agitated and indignant, which wasn’t all that unusual for him. But there was an underlying tension too…”All right,” I said to Freddie, “let’s go to Beit Jala and check it out.”

We drove in the chill gathering of darkness. We went into the small hospital and a young Palestinian doctor who spoke English soon appeared. Yes indeed, he said matter-of-factly, he had recently treated a number of students for broken bones. There were ten cases of broken arms and legs and many of the patients were still there, too seriously injured to leave. He took us to several rooms filled with boys in their mid-teens, an arm or leg, sometimes both, immobile under shining white plaster casts…They all said that for reasons unknown to them, Israeli troops had surrounded their two-story middle school while classes were underway. In several classrooms, on the second floor, the students were ordered to close all the windows. Then the troops exploded tear gas bombs and slammed shut the door, trapping the students with the noxious fumes. They panicked. In their rush to escape they fled from the rooms so fast that some of them went flying over the balcony to the asphalt and stony ground below.

About the third time we heard the same story, I noticed Freddie’s face. It was gray and stricken. He was shaking his head and wringing his gnarled hands. “Oh, man,” he said “this is too much. I’m getting out of here.” And he left, taking a bus back to Jerusalem. Afterwards, he never talked about Beit Jala.

My Israeli photographer, who had followed in his own car, was not looking much better. But he dutifully continued taking pictures of the injured boys…There could be no doubt about what had happened to them. Still, I wanted to see where the attack had occurred. The school was just up the hill. It was dark by now, but I had no trouble with a flashlight finding spent tear gas canisters with Hebrew lettering littering the ground…Now I was more determined to nail down the aspect of the story that had so upset my staff and astounded me: the cutting of hair. I had to admit to myself that I found it almost too bizarre to believe that Israelis would actually inflict on another people this most humiliating symbol of the Holocaust. On the other hand, my experience told me that Israeli hatred of Palestinians might make anything possible…

The next morning at Ramonda Tawil’s house I met several of the young men who had had their hair shorn. They had not been shaved but clumps of hair were missing from their heads as though roughly cut by a knife. They said they had been picked up by Israeli troops for no obvious reason and were ordered to do exercises and pick up litter and weeds, some of them through most of the night. They had heard that similar scenes had taken place all over the West Bank.

I returned to a sullen and nervous bureau where hanging in the air was the question of whether I was going to do a story. I announced I was.

Time gave the story prominent play and it evoked outrage by Israeli authorities and American Zionists…The atmosphere in Israel was even harsher…I was attacked to my face as an anti-Semite and shunned by some…Then a miraculous thing happened. Ezer Weizman, the father of Israel’s air force and an upright man, personally took the matter into his own hands. As defense minister, he appointed a commission to investigate the matter. It found the Beit Jala story true.

Shortly after that finding, Don left Israel amid worries about his personal well-being.

On return to the States he authored several highly acclaimed books on the Arab-Israeli confrontation.

Donald Neff died in 2015.

“On the Jericho Road” by James M. Wall

Volume 33, Issue 4, September-October, 2000

Jim Wall was but a few months into his tenure as editor of The Christian Century when, in 1973, he received an invitation from the American Jewish Committee (AJC) to take an all-expenses paid trip to Israel. At first he declined the offer, then accepted it on the condition he would pay his own expenses, while the AJC would arrange his travel, hotel accommodations, and itinerary.

In December 1973, he landed in Tel Aviv with, as he would later confess, absolutely no knowledge that the airport was built on the Palestinian town of Lydda, where the Death March occurred. What was impressed upon him throughout his AJC planned visit was the fear Israelis had of another Holocaust, this time by invading Arab armies, a Holocaust only they could prevent with a strong military force. Any fears the Palestinians might have about their future were unaddressed.

That, however, would change when the AJC arranged a meeting at the Holy Land Institute in Jerusalem. As Jim recalls it, he was surrounded by evangelical Christians who shared an intense loyalty to the Zionist state of Israel and who faulted him and The Christian Century for its hostility to Zionism prior to Israel’s becoming a state in 1948. At some point in the evening, an American Mennonite pastor, serving a three-year tour in Jerusalem, quietly approached Jim and asked if he could come by his hotel later that night “for a chat.” Jim agreed.

His name was LeRoy Friesen and when they met later that evening he told Jim he was hearing only one perspective. And he proposed that they travel together into the West Bank and up to the Golan Heights.

Jim agreed; and since he was paying his own way, the AJC host had no grounds to object.

What Jim experienced on his road to Jericho is best told in his own words:

LeRoy drove us in his VW coupe along the road to Jericho, the location for Jesus’s story about the Good Samaritan. Driving northward out of Jericho, we talked about the importance of the Jordan River valley in terms of both farming and security. We stopped along the highway to admire the fertile fields of Israeli crops that lay between us and the river.

We then left the highway and drove on a dirt road up a hill and stopped to talk with a Palestinian farmer, who was sitting in front of his house. I remember him as rather elderly, and I was struck by the resigned sadness in his manner. He pointed up the hill to his well, which reminded me of a Georgia sharecropper’s well, and we saw that it was connected to a pump that provided water to his modest-sized field.

Quite a distance farther up the hill was an Israeli well, surrounded by barbed wire and e

nclosed in a concrete casing. That well was much deeper, LeRoy explained, and pipes carried its water down the hill where we could see it spraying onto the Israeli fields in the Jordan Valley. I knew enough about aquifers to know that the deeper, more sophisticated Israeli well (its pipes buried beneath the soil) would soon render useless the farmer’ shallower well, with its open, above ground pipes.

What I saw that morning has shaped all of my subsequent understanding of the region. This was the strong dominating the weak: control, not sharing. Something was seriously wrong with this picture.

In that farmer’s sad, resigned face was my epiphany. The existential reality of injustice witnessed first-hand, as LeRoy knew, is a far more powerful teaching tool than injustice heard or read about.

Jim Wall would go on to make over 20 trips to the Holy Land, always insisting that half of the tour at least be with a Palestinian guide. He would serve as editor and publisher of The Christian Century until 1999, and later as a contributing editor from 2008 to 2017.

Jim honored AMEU by accepting membership on our Board of Directors and National Council, and by authoring two other Link articles, one in 2004 (“When Legend Becomes Fact”) and one in 2009 (“L’Affaire Freeman”).

It was while we were preparing this issue of The Link that we learned of his death this past March. Jim was an ordained Methodist minister, and he ended his “On the Jericho Road” article with these words: “The legacy of injustices between conquerors and conquered — catalogued at Camp David II as borders, refugees, settlements and Jerusalem — must sooner or later be morally and legally confronted, confessed and corrected.”

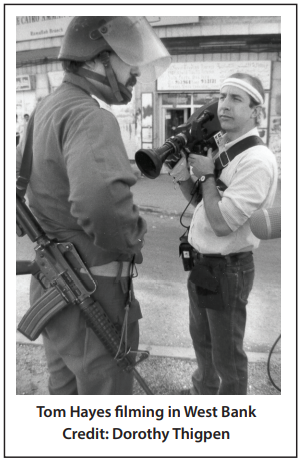

“People and the Land, Coming to a PBS Station Near You?” By Tom Hayes

Volume 30, Issue 5, November-December, 1997

Our Link articles run around 7,500 words over 16 pages. Only once have we extended it to 21,000 words over 24 pages. That was for Tom Hayes. An independent documentary film maker from Ohio, Tom had made two documentary films about Palestinians, “Native Sons” which he began filming in 1981, and “People and the Land” which he began in 1989. How he got the 27 crates containing nearly 20 miles of film footage shot in the Occupied Territories during the First Intifada past the Military Censor and the Passport Control Officer is a story in itself. Included in this footage was his focus on the number of children maimed by Israeli soldiers. From December 1987 through July 1993, 120,000 Palestinians were wounded, of whom 46,000 were under 16 years of age, leading to the speculation that the Army’s policy was not so much to kill as to maim the children as a way of pressuring their parents to leave their homeland.

But it’s the roadblocks he encountered here at home that are alarming. When a notice appeared in the Columbus Dispatch that he had made Native Sons, a documentary that focused on three Palestinian refugee families, he began receiving phone calls at all hours of the night, death threats against him and his then pregnant wife. He put wire mesh on the windows of his house to avoid a fire bombing. It didn’t help. Someone busted the window out. Next his phone line was cut. He talked to the police and told them about the documentary. They asked if he owned a gun. He began to feel like he was living in occupied territory.

When it later became known that Tom had received a grant from the George Gund Foundation for his Native Sons project, the Columbus Jewish Federation got a copy of the Gund proposal, which was not public record, and sent a barrage of correspondence to the Community Film Association (CFA), the group administering the Gund grant, trashing Tom and his film, and threatening to sue CFA board members for their personal assets.

CFA called Tom in to say that Dennis Aig, one of their board members, would be screening a rough cut of his film. Aig, who at the time was active with the Columbus Jewish Federation, ended his private screening in Tom’s cutting room yelling “You can’t say that!” A week later, CFA sent Tom a letter informing him that it found that he was engaging in propaganda and that he would forfeit a $20,000 grant he had received from the Ohio Arts Council (OAC). The CFA only agreed to honor its commitment after the OAC threatened to deny it funding in the future.

Tom also learned that the Ohio State University School of Fine Arts had booked a local theater for the premiere showing of Native Sons, only to be told later that the theater owner refused to show it. When the School of Fine Arts threatened to pull all its entries from his theater, the owner agreed to show Tom’s film.

Years later, when he was looking for funding for People and the Land, Tom got the nod from the Independent Television Service (ITVS), a service which Congress mandated be created through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to help under-served minorities increase programming diversity on PBS. In July 1991, ITVS called Tom to say his film had been selected for funding, but first they had some questions. Above all, they wanted to know where he got every penny for shooting the film. 18 months later, ITVS agreed to give the grant, this time with the stipulation that no public information about the film would be released without Tom’s approval.

ITVS submitted People and the Land to PBS for national release in February 1997. Sometime after that Gayle Loeber, Director of Broadcast Marketing for ITVS, called to say that PBS had “declined the program.” Loeber said ITVS could still prepare press materials and arrange a satellite feed to all 283 PBS affiliate stations, what is called a soft feed. These stations, at the discretion of the individual program directors, can air any of the dozens of soft feeds they receive each week. The first press release draft omitted mention of the foreign aid issues that the film starts and ends with. ITVS said they would make Tom’s correction. What they did was delete his sentence: People and the Land carries this humanistic perspective into a look at U.S. involvement in the Israeli occupation comparing Israel aid figures with cuts in human service programs for American citizens — $5.5 billion dollars in aid to Israel, 5.7 billion in cuts to human service programs.”

Tom called ITVS. A staff member told him Jim Yee was the new Executive Director and that he had ordered the copy cut.

In May 1997, ITVS called to say some of the PBS stations wanted more information about the program and why they should air it. Tom agreed to answer them. What Tom was not told was that ITVS had requested Mark Rosenblum, founder of Americans for Peace Now, to review the film. Rosenblum concluded that the film was “approximately 20% accurate”, that “97% of Palestinians are ruled by Palestinian authorities”, and that “Jews had attained a majority status in Palestine by 1870.” His review was sent to every programming director in the PBS system.

The Link contacted Mr. Rosenblum to confirm his comments. He denied ever writing a “review” or having put any comments in writing for ITVS, although he did say he had expressed certain opinions orally to someone at ITVS. Told that ITVS had quoted him as saying the documentary People and the Land was “20 percent accurate”, he denied ever giving a percentage of accuracy. Likewise, he denied saying 97% of Palestinians are ruled by Palestinian authorities or that Jews had reached a majority status in Palestine by 1870.

The Link reached Suzanne Stenson, formerly of the ITVS staff, who said she had transcribed Mr. Rosenblum’s comments on a laptop computer during an hour-long phone call and that, prior to its dissemination to the PBS stations, the text quoting Mr. Rosenbaum was emailed to him for review at his personal and business addresses. No response to these emails was ever received, she said.

Still, thanks to grassroots organizing, People and the Land was shown on at least 23 PBS stations, and over 160 DVD cassettes of the documentary have been distributed by AMEU, a record number for us.

In 2014, Tom and his crew returned to Palestine to document The Wall, the checkpoints, the humiliations, the killings. Why, you might ask him, go back for yet more aggravation? “When you know the truth, the truth makes you a soldier” Tom might reply, a favorite quote of his from Mahatma Gandhi. [Tom’s third trip to Palestine is recorded in our Nov.-Dec. 2015 Link “Between Two Blue Lines.” Ed.]

“Save the Musht and the Land of Palestine,” by Rosina Hassoun

Vol. 26, No. 4: Oct.-Nov. 1993

Rosina Hassoun delivered the first of four papers on “The State of Palestine,” a panel sponsored by the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee at its 1993 National Convention in Alexandria, Virginia. The other three presenters talked politics, everything from Israeli annexation of the Territories to Palestinian sovereignty over them. When the time came for questions, the 500-plus audience directed all its questions to the political analysts.

Then something unexpected happened. The session ended and the three analysts made their way out of the room. But not Rosina. She was surrounded by reporters and interviewers, as well as audience members fascinated by what she had to say. A half-hour later I managed to speak with her about writing a feature article for The Link.

Rosina speaks of paradigms, that is, of the images a people have of themselves and their land. Zionists, for example, see Palestine as a wasteland and a desert. For the World Zionist Organization, Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land.” Its aim was “to make the desert bloom.”

For the Zionist colonizers this dual image of wasteland and desert satisfied their three ideological imperatives: Ownership: Those who create something out of nothing get to keep it; Absorption: A wasteland offers a borderless capacity for colonization; and Exploitation: Jews, especially those from Europe, America and South Africa brought with them western attitudes towards resource usage, namely that resources are there for the taking. European and American Jews also brought western images of manicured lawns and swimming pools as part of their idealized lifestyles.

For Palestinians, their images of the land are traditionally those of: Motherhood: This paradigm of land as mother, found especially in their poetry, stems from the belief of Palestinians that they are descended from the multitudes of people who previously inhabited Palestine in an unbroken line dating back to the Canaanites and before; Fertility: This paradigm of fertile crescent or bread basket derives from the Palestinian system of food production founded on agricultural practices of planting citrus, olives, grains and vegetables with rock-terracing, practices that reflect ancient Nabatean and other early practices); Village: Palestinians developed relationships between the villages and cities for the flow of goods and services. This system led to the development of local dialects, costumes and village cultural distinctions.

Rosina spends the rest of her Link article showing how these paradigms apply to the different ways Palestinians and Israelis treat natural resources such as water, trees, and land. It is a fascinating exercise, and I encourage readers to go to our website and read pages 5-12 of her article. Her analysis is more relevant today than when she first presented it to that ADC audience back in 1993.

Which brings us to the Musht in the title of her article. It is a fish that swims in the Sea of Galilee, also called Christ’s fish or Saint Peter’s fish, and widely associated with the miracle of the loaves and fishes. It’s also a dying fish. Rosina concludes her article with these words:

In the end, saving the Musht may not be anyone’s priority. But sometimes, a small seemingly insignificant species acts as an indicator of the state of the environment. If it ceases to exist, a chain reaction ripples through the land.

The Musht may be sending us a warning that ecological collapse could come rapidly or sneak up slowly while everyone else is looking at other issues. While this generation of Arabs and Israelis fight over and negotiate the land, the environmental consequences of their actions may be destroying the very thing they both covet.

Update: Fishing stocks have continued to diminish in the Sea of Galilee due to overfishing and to a virus that infected the Musht. This led to a ban in April 2010 of commercial and recreational fishing in nesting and spawning grounds of the Musht.

Meanwhile Rosina, a doctoral student when she first sounded the alarm, has gone on to receive her PhD in Anthropology from Florida University, and is currently an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Saginaw Valley State University.

“When War Criminals Walk Free,” by Mads Gilbert, M.D.

Volume 45, Issue 5, December, 2012

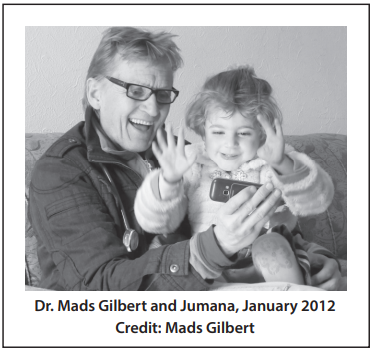

Mads Gilbert heads the Clinic of Emergency Medicine at University Hospital of North Norway. In 2009, he was one of two foreign doctors in al-Shifa Hospital during Israel’s Operation Cast Lead assault on Gaza. “We waded in death, blood and amputated limbs,” he wrote in his Link article, noting that, far too often, the victims were children. Two of these children he wants us to get to know: Jumana and Amal.

We meet Jumana, a nine-month-old girl, lying on her back, almost unarousable following anesthesia, most of her left hand is amputated.

A nurse tells Dr. Gilbert the tiny girl was a member of the Samuni family from the impoverished quarters of al-Zaitoun in the southern outskirts of Gaza City. Another nurse adds that Israeli ground forces had herded about a hundred members of the extended family, including women, children and elderly into a warehouse, where they stayed overnight without food or drink. The next morning, Israeli forces bombed the building.

Gilbert doubted it. But it was true. An investigation into the massacre would confirm that soldiers from the Israeli armed forces had systematically planned and executed the killing of 21 members of the Samuni family. Jumana was one of the youngest survivors.

For three days following the shelling, the casualties were trapped in the destroyed warehouse along with the dead bodies. Only then did the Israelis allow rescue services to enter the building. One of those casualties was Amal Samuni, a 9-year-old Palestinian schoolgirl and Jumana’s cousin. Like Jumana, she had been forced into the warehouse with her father, mother and siblings. At one point, when her father and smallest brother opened the door to face the Israeli soldiers to tell them, in Hebrew, that the building was filled only with civilians, women and children, both were shot dead at close range.

It was during the early morning shelling that Amal was hit by something on her head. When the solders allowed her to go, she was rushed to al-Shifa Hospital where Dr. Gilbert cared for her. Her lips were cracked and dried, and her body severely dehydrated, and she looked more like an old lady than a young schoolgirl. But she survived.

After the wounded were evacuated, the army demolished the building with the dead bodies inside. It was only possible to remove them from under the debris after the army withdrew, some two weeks later.

But, before they withdrew, the soldiers scrawled their mission with graffiti on the walls of the Samuni family home, some in Hebrew, many in crude English: “Arabs need 2 die”, “Die you all”, “Make war not peace”, “1 is down, 999,999 to go”, “The Only Good Arab is a Dead Arab.”

The warehouse massacre cost the lives of at least 26 members of the Samuni family, including 10 children and seven women. The Israeli Army later concluded in its “investigation” that the killing of civilians “who did not take part in the fighting” was not done knowingly and directly, or out of haste and negligence “in a manner that would indicate criminal responsibility.”

Three years after the massacre — it was New Year’s 2012 — Dr. Gilbert returned to Gaza to see how his patients were doing, especially Jumana and Amal. Jumana, then going on four, was managing well with her two-fingered left hand. And Amal, 12, was doing well in school, although she has terrible headaches. Dr. Gilbert tells their family he is going on another speaking tour to U.S. and Canadian universities, and he asks what they would like him to say. One of the adults replied: “Tell them this: Your tax money is killing our people!”

Update: In October 2014, on his annual medical visit to Gaza, Dr. Gilbert was stopped at the Israeli Erez checkpoint and banned indefinitely from entering Gaza. The reason: He posed a “security risk.”

Zionism: What Is It?

The Lydda Death March, the bombing of Iraqi synagogues, the poisoning of Palestinian wells, the corralling of Bedouin Arabs, the gassing of Beit Jala school children, the bias against Palestinian farmers, the ecological scarring of a fertile land, the massacre in Gaza, the bias, here in the U.S. against telling the Palestinian side of the story — this is the legacy of Zionism.

Google defines Zionism as a movement originally for the re-establishment and now for the development and protection of a Jewish nation in what is now Israel.

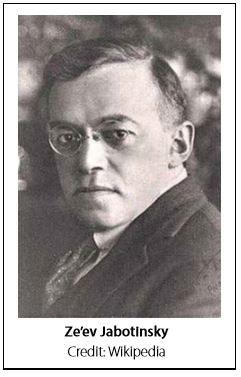

Norman Finkelstein received his doctoral degree from Princeton University for his dissertation “The Theory of Zionism.” In his Link article for December 1992 he distinguishes two basic types of nationalism: liberal nationalism with roots in the French Revolution and ethnic nationalism with roots in German Romanticism.

Liberal nationalism has as its main pillar the citizen: the state is constituted by its citizens and between citizens is complete legal equality. Romantic nationalism’s main pillar is the ethnic nation: each state belongs to a particular ethnic nation, and the latter occupies a privileged position in the state.

Historians, according to Finkelstein, generally agree on the Germanic origins of Zionism. He cites the Israeli historian Anita Shapiro who writes “It was the Romantic-exclusivist brand of nationalism that contained certain ideas able to function as a basis for an elaborated notion of a Jewish nation and national movement.”

It was also the Germanic notions of nationalism that culminated in Nazism. Revealingly, the only Jews for whom Hitler reserved any praise in “Mein Kampf” were the Zionists, whose affirmation of the national character of the Jew conceded the central Nazi tenet that, not withstanding his citizenship, the Jew is no German.

The Romantic essence of the Israeli state, according to Finkelstein, was reaffirmed in 1989 by a High Court decision that any political party which advocated complete equality between Jew and Arab can be barred from fielding candidates in an election. And, more recently, in 2018, the Israeli Knesset approved the ‘nation-state’ bill that promotes Jewish-only settlements, downgrades Arab language status and limits the right to self-determination to Jews only.

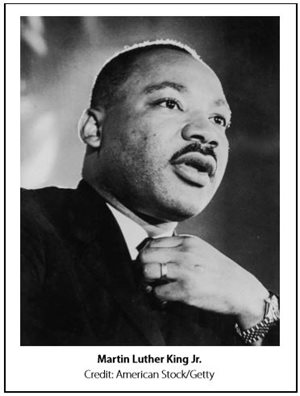

Criticism of Zionism: Is It Anti-Semitic?

This is the question posed by Allan Brownfeld in our December 2017 Link. He notes that, for many years now, there has been a concerted effort to redefine “anti-Semitism” from its traditional meaning of hatred of Jews and Judaism, to criticism of Israel and opposition to Zionism. Brownfeld, the editor of ISSUES, the quarterly journal of the American Council for Judaism, devotes much of his Link article to reviewing the long history of Jewish criticism of Zionism. It includes:

In 1919, in response to Britain’s Balfour Declaration calling for a “Jewish homeland” in Palestine, a petition was presented to President Wilson entitled “A Statement to the Peace Conference.” It rejected Jewish nationalism and held against the founding of any state upon the basis of religion and/or race. Among its prominent Jewish signers were Jesse L. Straus, co-owner of Macy’s ,and Adolph Ochs, publisher of The New York Times.

In 1938, alluding to Nazism, Albert Einstein warned an audience of Zionist activists against the temptation to create a state imbued with “a narrow nationalism within our own ranks.”

In May 1948, in the midst of the hostilities that broke out after Israel unilaterally declared independence, Martin Buber despaired, “This sort of Zionism blasphemes the name of Zion; it is nothing more than one of the crude forms of nationalism.”

In his 1973 book “Israel: A Colonial-Settler State,” the French Jewish historian Maxime Rodinson wrote: “Wanting to create a purely Jewish or predominately Jewish state in Arab Palestine in the 20th century could not help but lead to a colonial-type situation and the development of a racist state of mind, and in the final analysis to a military confrontation.”

Brownfeld concludes that there is no historic basis for claiming that anti-Zionism is a form of anti-Semitism, and that the only purpose in making such a charge is to silence criticism of Israel and its policies.

To be sure, anti-Semitism exists and should be confronted whenever it raises its ugly head; but legitimate criticism of a colonial-settler movement is not anti-Semitism.

What Is Christian Zionism?

Christian Zionism is the belief of some Christians that the return of Jesus to the Promised Land is a sign of Christ’s immanent Second Coming, when true Christians will be raptured in the air, while the rest of mankind is slaughtered; 144,000 Jews will bow down before Christ and be saved, but the rest of Jewry will perish. Politically, they represent a significant bloc, with a potential 40 million followers in the U.S. and 70 million worldwide. Two Link issues offer insight into these believers:

“Christian Zionism” (November 1983) by O. Kelly Ingram, professor at the Divinity School of Duke University. This issue traces the roots of Christian Zionism back to 17th century England, and shows the influence it had on the signers of the Balfour Declaration.

“Beyond Armageddon” (October-November 1992) by Donald Wagner, then Director of Middle East Programs for Mercy Corps International. Wagner documents the growing influence of Christian Zionism among U.S. televangelists.

What Did The U.N. General Assembly Say About Zionism?

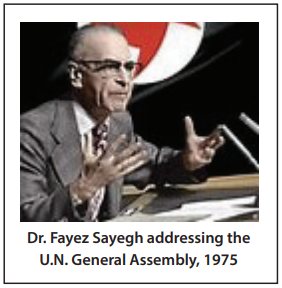

U.N. General Assembly Resolution 3379 determined that Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination. The resolution was based on four statements delivered to the General Assembly by Dr. Fayez Sayegh, a Palestinian intellectual employed by Kuwait. His 52-page documentation is available and downloadable on our website under AMEU Publications.

While working with Dr. Sayegh on editing his manuscript, I asked him what, apart from not being allowed to return to his homeland, was the hardest part of his exile. He thought for a moment, then replied: “The fact that my children don’t speak Arabic.”

In 1991, when Israel made revocation of Resolution 3379 a precondition of its entering the Madrid Peace Conference, the U.N., under fierce pressure from the U.S., complied.

To Conclude:

Many are responsible for AMEU’s Archive.

I think of the Rev. Humphrey Walz, a Presbyterian minister, who edited The Link for its first two years. After WWII Humphrey worked in New York for the resettlement of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust then, following 1948, he aided in the resettlement of Palestinian refugees.

I think of Grace Halsell, an acclaimed journalist, whose Journey to Jerusalem was one of the first books by a mainstream American journalist to report on what the Palestinians call their Catastrophe. Grace would go on to write four feature articles for The Link, and serve on AMEU’s Board of Directors for 18 years, until her death in 2000.

I think of Bob Norberg, the president of AMEU from 2005 to 2015. During that time he created AMEU’s website, and its digital archive going back to 1968. And today, each new issue of The Link is posted online by his son Jeffrey Norberg.

I think of Jane Adas, AMEU’s current president. In 1991, I received a postcard, signed “Jane Adas,” with the one sentence: “If you can use volunteer help, I’d be happy to come in a day each week.” Jane, it turned out, was Prof. Jane Adas of Rutgers University, one of the most knowledgeable people I know on the Palestine question. Five times she has put her body where her words are by spending three to nine week stints in Hebron with the Christian Peacemaker Teams, where she stood between Palestinians who live there and Jewish settlers who harass them in an attempt to steal more of their land. In 2001, she wrote a Link issue on her Hebron experience, “Inside H-2.” In 2009, Jane was one of the first Americans to get inside Gaza to see the devastation wrought by Israel’s Operation Cast Lead; see her 2009 Link article “Spinning Cast Lead.” Today, in addition to being AMEU’s third president, she is the proofreader par excellence of every Link issue. Never has a postcard heralded such a treasure.

When I was in high school, I read a book on the Holocaust. What I mostly recall is a comment by a woman survivor of Auschwitz who said that what pained her most deeply was the thought that nobody outside the camp would ever know the hell they were going through — much less care.

My hope is that Palestinians will see our Archive as a witness to their Catastrophe: that their suffering is known — and that we do care. ■

Welcome Nicholas Griffin

It is with the greatest pleasure that A.M.E.U. welcomes Nicholas Griffin as its next Executive Director.

Nicholas is an independent consultant who has worked with the U.N. Department of Public Information, the American University in Cairo, Youth Recreational Facilities in the West Bank, as well as projects in Algeria, Ghana, Jordan, Morocco, and Niger.

He is a long-time supporter of A.M.E.U. and well acquainted with our institutional goals. Along with publishing and editorial experience, he brings a firm grasp of the digital age, its opportunities and challenges.

When I became executive director, some 43 years ago, someone told me: “Remember, in your job, as in life, money isn’t everything. But,“ he was quick to add, “it is way ahead of whatever comes third.” I told Nick we had a loyal band of donors that he could count on as he leads AMEU into a future of better Middle East Understanding.

It was inevitable that when the coronavirus pandemic reached the occupied Palestinian territories, as it did in early March, it would find its first purchase in Bethlehem, a few miles south-east of Jerusalem in the occupied West Bank.

Staff at the Angel Hotel in Beit Jala, one of Bethlehem’s satellite towns, tested positive after they were exposed to a group of infected Greek tourists. Israel worked hurriedly with the Palestinian Authority – the Palestinians’ permanent government-in-waiting in the occupied territories – to lock down Bethlehem. Israel was fearful that the virus, unlike the city’s Palestinian inhabitants, would be difficult to contain. Contagion might spread quickly to nearby Palestinian communities in the West Bank, then to Jewish settlements built illegally by Israel on Bethlehem’s lands, and finally on into Israel itself.

The Palestinian territories were under a form of lockdown long before the arrival of the coronavirus, however. Israel, the occupying power, has made sure that the entire Palestinian population is as isolated from the world as possible – their voices silenced, their experiences of oppression and brutality at Israel’s hands near-invisible to most of the Israeli public and to outsiders.

But Bethlehem, the reputed site of Jesus’s birth 2,000 years ago, is the one Palestinian area – outside East Jerusalem, which has been illegally annexed by Israel – that has proved hardest for Israel to hermetically seal off. During visits to the Church of the Nativity, tourists can briefly glimpse the reality of Palestinian life under occupation.

Some 15 years ago Israel completed an 26 foot-high concrete wall around Bethlehem. On a typical day – at least, before coronavirus halted tourism to the region – a steady stream of coaches from Jerusalem, bearing thousands of Christian pilgrims from around the world, came to a stop at a gap in the concrete that served as a checkpoint. There they would wait for the all-clear from surly Israeli teenage soldiers. Once approved, the coaches would drive to the Nativity Church, their passengers able to view the chaotic graffiti scrawled across the wall’s giant canvas, testifying to the city’s imprisonment and its defiance.

Like the plague-bearing Greeks, visitors to Bethlehem could not avoid mixing, even if perfunctorily, with a few locals, mostly Palestinian Christians. Guides showed them around the main attraction, the Church, while local officials and clergy shepherded them into queues to be led down to a crypt that long ago was supposedly the site of a stable where Jesus was born. But unlike the Greek visitors, most pilgrims did not hang around to see the rest of Bethlehem. They quickly boarded their Israeli coaches back to Jerusalem, where they were likely to sleep in Israeli-owned hotels and spend their money in Israeli-owned restaurants and shops.

For most visitors to the Holy Land, their sole meaningful exposure to the occupation and the region’s native Palestinian population was an hour or two spent in the goldfish-bowl of Bethlehem.

In recent years, however, that had started to change. Despite the wall, or at times because of it, more independent-minded groups of pilgrims and lone travelers had begun straying off grid, leaving the Israeli-controlled tourism trail. Rather than making a brief detour, they stayed a few nights in Bethlehem. A handful of small, mostly cheap hotels like the Angel catered to them, as did restaurants and souvenir stores around the church.

In tandem, a new kind of political tourism based in and around Bethlehem had begun offering tours of the wall and sections of the city, highlighting the theft of the city’s land by neighboring Jewish settlements and the violence of Israeli soldiers who can enter Bethlehem at will.

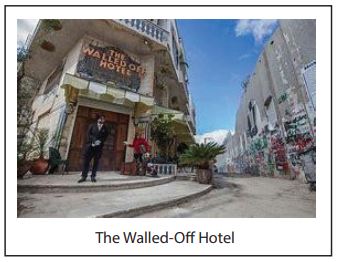

A few years ago, the famous anonymous British graffiti artist Banksy gave a major boost to this new kind of immersive tourism by allying with a Bethlehem tour guide, Wisam Salsa, to open the Walled-Off Hotel. They converted an old building boxed in by the wall, liberally sprinkling it with Banksy’s subversive artworks about the occupation, as well as installing a gallery exhibiting the work of Palestinian artists and a museum detailing the occupation’s history and Israel’s well-tested methods of control and repression.

Admittedly, few visitors managed to get a room in Banksy’s small hotel, but many more came to sit in the lobby and sip a beer, produced by one of a handful of newly emerging breweries run by Christian Palestinians, or add some graffiti to the wall just outside with the help of a neighboring art supplies shop.

Before coronavirus, the Walled-Off offered daily tours of Aida, a refugee camp attached to Bethlehem, whose inhabitants were expelled from some of the more than 500 Palestinian communities Israel erased in 1948 – in the Nakba, or Catastrophe – to create a Jewish state on their homeland. There, visitors not only learned about the mass dispossession of Palestinians, sponsored by the western powers, that made Israel’s creation possible, but they heard the camp’s inhabitants tell of regular violent, night-time raids by Israeli soldiers and of the daily struggle for survival when Israel tightly controls and limits essentials like water.

Until the coronavirus did Israel’s work for it, Israeli authorities had noted with growing concern how more tourists and pilgrims were staying in Bethlehem. According to Israeli figures, there are about a million tourist overnights annually in Bethlehem. And that figure was growing as new hotels were built, even if the total was still a tiny fraction of the number of tourists staying in Israel and Israeli-ruled East Jerusalem.

The new trend disturbed the Israeli authorities. Bethlehem was proving an Achilles’ heel in Israel’s system of absolute control over the Palestinians for two reasons.

First, it brought money into Bethlehem, providing it with a source of income outside Israel’s control. The Israeli authorities have carefully engineered the Palestinian economy to be as dependent on Israel as possible, making it easy for Israel to punish Palestinians and the PA economically for any signs of disobedience or resistance. Aside from its tourism, Bethlehem has been largely stripped of economic autonomy. After waves of land thefts by Israel, the city now has access to only a tenth of its original territory, and has been slowly encircled by settlements. The city’s residents have been cut off from their farmland, water sources and historic landmarks. Jerusalem, once Bethlehem’s economic and cultural hinterland, has become all but unreachable for most residents, hidden on the other side of the wall. And those working outside the tourism sector need a difficult-to-obtain permit from Israel’s military authorities to enter and work in low-paying jobs in construction and agriculture inside Israel, the settlements or occupied Jerusalem. Israel’s second ground for concern was that foreign visitors staying in Bethlehem were likely to learn first-hand something of the experiences of the local population – more so than those who simply made a brief detour to see the church. A self-serving narrative about Palestinians central to Israeli propaganda – that Israel stands with the west in a Judeo-Christian battle against a supposedly barbaric Muslim enemy – risked being subverted by exposure to the reality of Bethlehem. After all, anyone spending time in the city would soon realize that it includes Palestinian Christians only too ready to challenge Israel’s grand narrative of a clash of civilizations.

From Israel’s point of view, a stay in Bethlehem might also open tourists’ eyes in dangerous ways. They might come to understand that, if anyone was behaving in a barbaric way and provoking an unresolvable, religiously inspired clash, it was not Palestinians – Muslim or Christian – but Israel, which has been brutally ruling over Palestinians for decades.

For both reasons, Israel wished to prevent Bethlehem from becoming a separate, rival hub for tourism. It was impossible to stop pilgrims visiting the Church of the Nativity, but Israel could stop Bethlehem developing its own tourism industry, independent of Israel. The wall has been part of that strategy, but it failed to curb the development of new tourism ventures – and in some cases, as with the Banksy hotel, had actually inspired alternative forms of tourism.

In early 2017 the Israeli authorities finally acted. The daily Haaretz newspaper revealed that the interior ministry had issued a directive to local travel agencies warning them not to allow their pilgrimage groups to stay overnight in Bethlehem, with the implication that the firms risked losing their licenses if they did so. According to Haaretz, the government claimed that “potential terrorists were traveling with groups of tourists”.

Bethlehem is lucky that, unlike other Palestinian communities, it has allies Israel cannot easily ignore. Haaretz’s exposure of the new policy led to a rapid backlash. International churches, especially the Vatican, were worried that it was the thin end of a wedge that might soon leave the City of the Nativity off-limits to its pilgrims. And Israeli travel agencies feared their business would suffer. Pilgrim groups from poorer countries that could not afford Jerusalem’s high prices, especially for accommodation, might stop coming to the Holy Land.

As one agent told Haaretz: “The meaning of a letter like this is the end of incoming tourism from India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and eastern European countries like Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine. All the tourists who visit Israel and sleep in Bethlehem are doing that primarily to reduce costs.” The loss of such tourists not only threatened to deprive Bethlehem of the benefits of tourism but threatened Israel’s much larger tourism sector. Soon afterwards, the Israeli authorities backtracked, saying the directive had been a draft issued in error.

Why the Shrinkage?

Bethlehem’s plight – a microcosm of the more general difficulties faced by Palestinians under occupation – offers insights into why the region’s Palestinian Christian population has been shrinking so rapidly and relentlessly.

The demographics of Bethlehem offer stark evidence of a Christian exodus from the region. In 1947, the year before Israel’s creation, 85 percent of Bethlehem’s inhabitants were Christian. Today the figure stands at 15 percent. Christians now comprise less than 1.5 percent of the Palestinian population in the West Bank – some 40,000 of a population of nearly 3 million – down from 5 percent in the early 1970s, shortly after Israel occupied the territory in 1967.

In 1945 Bethlehem had nearly 8,000 Christian residents, slightly more than the 7,000 who live there today. Natural growth should mean Bethlehem’s Christian population is many times that size. There are, in fact, many times more Palestinian Christians overseas than there are in historic Palestine. The 7,000 Christians of Beit Jala, next to Bethlehem, are outnumbered by more than 100,000 family members who have moved to the Americas.

Israel ostensibly professes great concern about this decline, but actually it is only too happy to see native Christians depart the region. Their exodus has helped to make Israel’s clash of civilizations narrative sound more plausible, bolstering claims that Israel does indeed serve as a rampart against Muslim-Arab terror and barbarism. Israel has argued that it is helping Christian Palestinians as best it can, protecting them from their hostile Muslim neighbors. In this way, Israel has sought to mask its active role in encouraging the exodus.

The rapid decline in the numbers of these Christians reflects many factors that have been intentionally obscured by Israel. Historically, the most significant is that Palestinian Christians were nearly as badly impacted as Palestinian Muslims by the mass expulsions carried out by Zionist forces in 1948. In total, some 80 percent of all Palestinians living in what became the new state of Israel were expelled from their lands and became refugees – 750,000 from a population of 900,000. Those forced into exile included tens of thousands of Christians, amounting to two-thirds of the Palestinian Christian population of the time.

Palestinian Christians who remained in historic Palestine – either in what had now become Israel or in the territories that from 1967 would fall under Israeli occupation – have naturally shrunk over time in relation to the Muslim population because of the latter’s higher birth rates. Palestine’s Christians mostly lived in cities. Their urban lifestyles and generally higher incomes, as well as their greater exposure to western cultural norms, meant they tended to have smaller families and, as a result, their community’s population growth was lower.

But rather than acknowledge this historical context, Israeli lobbyists seek to exploit and misrepresent the inevitable tensions and resentments caused by the mass displacements of the Nakba, developments that had a significant impact on traditionally Christian communities like Bethlehem. During the events of 1948, as rural Palestinian villages were ethnically cleansed by Zionist forces, the refugees sought shelter either in neighboring states like Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, or in West Bank cities.

Bethlehem found its demographics transformed: an 85 percent Christian majority before the Nakba has been reversed into an 85 percent Muslim majority today. These dramatic social and cultural upheavals – turning the city’s majority population into a minority – were not easy for all Bethlehem’s Christian families to accept. It would be wrong to ignore the way these changes caused friction. And the resentments have sometimes festered because they are incapable of resolution without addressing the source of the problem: Israel’s mass dispossession of Palestinians, and the continuing tacit support for these abuses by the international community.

Given this context, it has been easy for inter-family rivalries and conflicts that are inevitable in a ghettoized, overcrowded community like today’s Bethlehem to be interpreted by some members of the minority group as sectarian, even when they are not. The lack of proper law enforcement in Palestinian areas in which Israel rather than the PA is the ultimate arbiter of what is allowed has left smaller Christian families more vulnerable in conflicts with larger Muslim families. In the competition for diminishing resources, family size has mattered. And whereas globalization has tended to encourage increased identification among Palestinian Christians with the west and its more secular norms, the same processes have entrenched a religious identity among sections of the Muslim population who look to the wider Middle East for their ideas and salvation. Consequently, a cultural gap has widened.

These problems exist but it would be wrong to exaggerate them – as Israel’s loyalists wish to do – or to ignore who is ultimately responsible for these tensions. That is not a mistake most Palestinian Christians make. In a recent survey of Christians who have emigrated, very few pointed to “religious extremism” as the reason for leaving the region – just 3 percent. The overwhelming majority cited reasons relating in some way to Israel’s continuing malevolent role in controlling their lives. A third blamed a “lack of freedom”, a quarter “worsening economic conditions”, and 20 percent “political instability.”

To make sense of the specific problems faced by the Christian community, other historical contexts need to be understood. Palestinian Christians break down into four broad communities. The first is the Eastern Orthodox Churches, dominated by the Greek Orthodox. The second is the Catholic Churches, led by the “Latin” community that looks towards Rome, although they are outnumbered among Palestinians by Greek and Syrian Catholics. The third category is the Oriental Orthodox churches, which include the Copts, Armenian and Syrian Orthodox. And finally, there are various Protestant Churches, including the Anglicans, Lutherans and Baptists.

Long before Israel’s creation on most of the Palestinians’ homeland, Christians were concentrated in and around Palestine’s urban centers. In Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Nazareth, large numbers of Christians coalesced around sites associated with Jesus’s life. This tendency was reinforced as Palestine’s cities flourished and expanded from the 18th century onwards under Ottoman rule. The Ottomans encouraged the immigration of Christians to these centers of worship and cultivated a confessional system that made conditions attractive for the foreign Churches.

The result was a relatively privileged urban Christian population that consisted largely of merchants and traders, and benefited from the resources poured in by the international Churches as part of their missionary work, including schools and hospitals. Christians were typically wealthier, better educated and healthier than their Muslim counterparts often living nearby in isolated rural communities as peasant farmers. In addition, Christian families had good connections to the international Churches through local clergy, as well as the staff of Church-run schools and hospitals.

Those differences have proved significant as Palestinian Christians and Muslims alike have struggled under Israeli colonization, whether inside Israel’s internationally recognized borders or in the occupied territories.

Israel’s institutionalized racism towards Palestinians – systematic land thefts, uninhibited state and settler violence, as well as restrictions on movement and the denial of educational and employment opportunities – have put pressure on all Palestinians to leave. But Christians have enjoyed significant advantages in making their escape. They could tap their connections in the Churches to help them settle abroad, chiefly in the Americas and Europe. And that path was made easier for many given that relatives had already established lives overseas following the mass expulsions of 1948. As a result, the emigration of Palestinian Christians is generally reckoned to have been around twice that of Muslims.

Israel’s oft-repeated claim that Hamas and the Palestinian Authority are responsible for the exodus of Christians out of the Holy Land is given the lie simply by examining the situation of Palestinian Christians both inside Israel, where neither Hamas nor the PA operate, and in East Jerusalem, where the influence of both has long been negligible. In each of those areas, Israel has unchallenged control over Palestinians’ lives. Yet we can see the same pattern of Christians fleeing the region.

And the reasons for Gaza’s tiny Palestinian Christian population, today numbering maybe only 1,000, to leave their tiny, massively overcrowded enclave, which has been blockaded for 13 years by Israel, barely needs examining. True, it has been hard for these Christians – 0.0005 percent of Gaza’s population – to feel represented in a territory so dominated by the Islamic social and cultural values embodied by the Hamas government. But there is little evidence they are being persecuted.

On the other hand, there is overwhelming proof that Gaza’s Christians are suffering, along with their Muslim neighbors, from Israel’s continuing violations of their most fundamental rights to freedom, security and dignity.

The picture in the West Bank, meanwhile, needs closer study. As noted, Palestinian Christians have generally enjoyed historic privileges over their Muslim compatriots that derive from their historic connections to the Churches. They have been able to exploit tourism as guides, drivers and guesthouse owners. They enjoy greater access to church-run schools and, as a consequence, improved access to higher education and the professions. They possess more valuable urban land, and many own shops and businesses in the cities. There are both Muslim and Christian lawyers, shopkeepers and business owners, of course, but proportionately more Christians have belonged to the middle classes and professions because of these various advantages.

While Israel’s occupation policies have harshly impacted all Palestinians, some have been hit harder than others. And those who have tended to suffer most live not in the main cities, which are under very partial Palestinian rule, but in rural areas and in the refugee camps. Those in the camps, in places such as Aida, next to Bethlehem, lost their lands and property to Israel and have had to rebuild their lives from scratch since 1948. Those living in isolated farming communities designated by the Oslo accords as “Area C” (a temporary designation that has effectively become permanent) are fully exposed to Israel’s belligerent civil and military control.

The residents of these communities have few opportunities to earn a living and have been most vulnerable to Israeli state and settler violence, as well as land thefts and the severe water restrictions imposed by Israel. In practice, these precarious conditions are endured disproportionately by Muslim Palestinians rather than Christians.

Nonetheless, Israel’s policies have increasingly deprived urban Christian families of the opportunities they had come to expect – the kind of opportunities westerners take for granted. And significantly, unlike many Muslim Palestinians, Christians have continued to enjoy one privilege: an escape route out of the region to countries where they have a chance to live relatively normal lives.

The damage to Christian life has been felt particularly keenly in relation to movement restrictions – one of the ways Israel has established a system of near-absolute control over Palestinian life. Those involved in trade and business, as many Christians are, have struggled to succeed as those restrictions have intensified over the past quarter-century, since the introduction of measures under the Oslo accords. An elaborate system of checkpoints and permits was established to control Palestinians’ freedom to move around the occupied territories and to enter Israel in search of work. Over time the system was enforced by a lengthy steel and concrete “separation barrier” that Israel began building nearly two decades ago.

Taybeh’s Beer Challenge

Typifying the difficulties of trading under these circumstances is the Taybeh micro-brewery in a West Bank village of the same name, in a remote location north of Ramallah overlooking the Jordan Valley. Taybeh is exceptional: its 1,300 inhabitants comprise the last exclusively Christian community in the occupied territories. The village – its name means both “good” and“delicious” in Arabic – is reputedly on the Biblical site of Ephraim. A small church marks the spot where Jesus reputedly retired with his disciples shortly before heading to Jerusalem, where he would be crucified. Taybeh has its own Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox schools, and a Catholic nursing home.

Nonetheless, Taybeh has long been in demographic meltdown. Today, its population is dwarfed by those of its diaspora: some 12,000 former residents and their descendants live abroad, mostly in the United States, Chile and Guatemala. Daoud and Nadim Khoury, two brothers who were themselves raised in the US, established the Taybeh brewery shortly after their return to the West Bank village under the Oslo accords. The business depended on the experiences and connections they had gained abroad.

For them, developing a sustainable business like the brewery was a way to halt and reverse the gradual demise of their village and the loss of its Christian heritage. They feared that any further decline in numbers would leave Taybeh’s lands and its ancient olive groves vulnerable to takeover by the three Jewish settlements that surround the village. The business was seen as a way to save Taybeh.

Maria Khoury, Daoud’s Greek wife, whom he met at Harvard, says the conditions of village life have continued to deteriorate. Unemployment stands at 60 percent, and Israel shuts off the water four times a week to preserve supplies for the Jewish settlements. The drive to the nearest Palestinian city, Ramallah, takes five times longer than it did 20 years ago – when it took little more than 15 minutes. That was before checkpoints and roadblocks were established on local roads to protect the settlers.

The Khourys have succeeded in their ambition to develop a range of award-winning beers made to the highest purity standards. The family has expanded into making boutique wines, and has built a prestige hotel in the village center, belying Taybeh’s small size. An annual Oktoberfest, modeled on German beer-drinking celebrations, has helped to put the remote village on the map. And a few restaurants have opened as Taybeh has tried to reinvent itself, with limited success, as a weekend-break destination.

But despite all these achievements, their larger ambitions have been foiled. Movement restrictions imposed by Israel’s military authorities have stymied efforts at growing the business. With a domestic market limited by opposition to alcohol consumption among most of the Palestinian population, Taybeh brewery has depended chiefly on exports to Europe, Japan and the US. But the difficulties of navigating Israel’s hostile bureaucracy have sapped the business of money, time and energy, making it hard to compete with foreign breweries.

Daoud told me at one Oktoberfest that the brewery faced Israeli “harassment in the name of security.” He noted that even when the crossing points were open, Israel held up the company’s trucks for many hours while bottles were unloaded and individually inspected with sniffer dogs. Then the bottles had to be reloaded on to Israeli trucks on the other side of the checkpoint. Apart from local spring water, all the beer’s ingredients and the bottles have to be imported from Europe, adding further logistical problems at Israeli ports. The ever-creative Khourys have been forced to circumvent these problems by licensing a plant in Belgium to produce its beers for foreign export. But that has deprived the village of jobs that could have gone to local families.

And while the Khourys struggle to get their products into Israel, Israel has absolute freedom to flood the occupied territories with its own goods. “The policy is clearly meant to harm businesses like ours. Israel freely sells its Maccabee and Goldstar beers in the West Bank,” Daoud told me.

Such experiences are replicated for Palestinian businesses, big and small, across the West Bank.

In Jerusalem, the Christian population has been shrinking too, even though the city has been entirely under Israeli control since its eastern neighborhoods were occupied and illegally annexed by Israel in 1967. The Palestinian Authority was briefly allowed a minimal presence in East Jerusalem in the late 1990s, but was effectively banished when the second intifada erupted a few years later, in 2000. A similar fate soon befell Jerusalem’s politicians associated with Hamas. After they won the Jerusalem seats in the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections, Israel expelled them to the West Bank.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Israel has not been keen to provide official figures for the exodus of Christians from Jerusalem. However, rather than growing, as one would have expected over the past five decades, the numbers have dropped significantly – from 12,000 in 1967 to some 9,000 today, according to Yousef Daher, of the Jerusalem Interchurch Center, located in Jerusalem’s Old City. Of those, he estimated that no more than 2,400 remained in the Christian Quarter of the Old City, where Israel has made life especially difficult.

Jerusalem is historically, symbolically, spiritually and economically important to the Palestinian people, and houses key Muslim and Christian holy sites. It has long been regarded by Palestinians as the only possible capital of their future state. But Israel views the city in much the same terms – as the religious and symbolic heart of its hybrid religious and ethnic national project. It has shown no interest in sharing the city as a capital, and has instead viewed it in zero-sum terms: whatever benefits Israel requires a loss to the Palestinians.

Gradually Israel’s stranglehold over Jerusalem has become complete. The wall it began building through the city more than 15 years ago has not only separated Palestinians in Jerusalem from Palestinians in the West Bank but has divided the city itself, placing more than 100,000 Palestinians on the wrong side, cutting them off from the city of their birth.

Two years ago, President Donald Trump added a US seal of approval by recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moving the US embassy there.

Those Palestinians in occupied East Jerusalem still on the “Israeli” side of the wall have found themselves isolated and ever more vulnerable to the abuses inherent in Israel’s system of control. They have suffered planning restrictions that make it almost impossible to build homes legally. Israel demolishes dozens of Palestinian houses every year in the city, leading to ever greater overcrowding. Meanwhile, Israel has seized vast tracts of land in East Jerusalem for its illegal settlements and has helped Jewish settlers take over Palestinian homes.

The city’s security forces act as an occupying power in Palestinian neighborhoods, while city authorities pursue an official policy of “Judaization,” making Jerusalem more Jewish. Israel has accorded the city’s native Palestinian population a “residency” status that treats them as little more than immigrants. Many thousands who have left the city for extended periods to study or work abroad have returned to find their residency permits revoked.

The city’s Christian residents face similar problems to Muslims. But as a very small community, they have also faced specific pressures. Israel’s policy of cutting off Jerusalem from the West Bank, and especially from the nearby cities of Bethlehem and Ramallah, has left the city’s Christians particularly isolated. With many working as merchants and traders, the so-called “separation” policy has hit them hard economically.

Similarly, because the communal marriage pool is small for Christians in Jerusalem, many have been forced – at least, before the wall was erected – to search for a spouse among Christian populations nearby in the West Bank. That now leaves them disproportionately exposed to Israel’s increasingly draconian family unification policies. Typically Jerusalem’s Palestinians are denied the right to live with a West Bank spouse in the city, or to register the children of such marriages as Jerusalem residents. That has forced many to move into the West Bank or abroad as the only way to stay together.

As in Bethlehem, many of Jerusalem’s Christians work in tourism, either as tour guides or as owners of souvenir shops in the Old City’s Christian Quarter. That has proved a particularly precarious way to make a living in recent decades, with tourism collapsing on repeated occasions: during two lengthy intifadas, during Israel’s attacks on Gaza, and now from the coronavirus.

Israel will soon make it even harder for the Old City traders to make a living, when it completes a cable car into East Jerusalem. Currently many tourists enter via Jaffa Gate into the Christian Quarter, where shopkeepers have a chance to sell them goods and souvenirs. But the cable car will “fly in” tourists from a station in West Jerusalem directly to an illegal settlement complex at the City of David in Silwan, just outside the Old City walls. From there, either they will be guided straight into the Jewish Quarter through Dung Gate or they will pass through a network of underground passages lined with settler-owned shops that will take them to the foot of the Western Wall. The aim appears to be not only to make the Old City’s Palestinian population invisible but to deprive them of any chance to profit from tourism.

Land Sales by Churches

But the problem runs deeper still for Palestinian Christians – and is felt especially acutely in Jerusalem. Local Christians have found themselves effectively pawns in a three-way international power-play between Israel, the established, land-owning Churches in the region, primarily the Vatican and Greek Orthodox Churches, and the evangelical movements. None of the parties represent their interests.

It is easy for pilgrims to ignore the fact, as they tour the Holy Land, that the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches are not local. They are vast foreign enterprises, based out of the Vatican and Greece, that are as concerned with their commercial viability and diplomatic influence on the global stage as they are with the spiritual needs of any specific flock, including Palestinian Christians. And in recent years that has become increasingly evident to local congregations.