By Ilan Pappe

On Friday, May 14, 1948, the members of the “People’s Council,” the makeshift parliament of the Jewish community in Palestine, convened in Tel-Aviv to listen to David Ben- Gurion read aloud Israel’s Proclamation of Independence.

The reading was broadcast on local radio and heard around the world. In years to come, it would be treated in Israel as an unwritten constitution that had no binding legal powers but provided moral guidance for the Israeli parliament, the Knesset.

Its model was the American Constitution and in order to adapt it to that document an American Jew, an academic scholar and a rabbi, Shalom Zvi Davidowitz, joined the team that articulated the final draft of the proclamation.

The proclamation summarizes the consensual Zionist narrative of the day, with all its principal fabrications, historical distortions and total denial of the native population and its fate. And yet miraculously, without any explanation, twice in the proclamation the natives are mentioned, as if they appeared out of the blue. First they are referred to as the people who benefited from the Zionist endeavour in Palestine that made the desert bloom and modernized the primitive land beyond recognition. More importantly, they are alluded to as future citizens of the Jewish State whose treatment in the future would prove that the Zionist movement founded the only democracy in the Middle East.

Here is the relevant paragraph:

THE STATE OF ISRAEL will be open for Jewish immigration and for the Ingathering of the Exiles; it will foster the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; it will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

This particular paragraph was the window dressing aimed at safeguarding Israel’s future international image and status. While the historical narrative in the proclamation described accurately the international complacency in the dispossession of Palestine, it also incurred the promise that this colonialist act would be redeemed by the foundation of the only democracy in the Middle East.

That promise of a democracy is not the reason why members of the international community still support Israel today or at least turn a blind eye to its criminal policies vis-à-vis the Palestinians. Their reasons for doing so are complex and this is not the place to explore them. But this pledge to democracy is the convenient pretext for Jews around the world, liberals, socialists and democrats in the West and their counterparts inside Israel, for providing the immunity other states would never enjoy had they pursued similar policies.

The main litmus test, as offered by the proclamation itself, for examining the democratic nature of the future state is the treatment of the non-Jewish minority in its midst.

By itself this was a problematic notion in that, even as the final draft was being written, that minority was being subjected to an ethnic cleansing operation that had begun three months earlier. And quite a few of those signing the proclamation were privy to the plans to complete the ethnic cleansing operation in such a way that it would be very easy to grant rights to a minority that would not be there.

In any event, the document proved more important than intended as a small minority did remain in the Jewish state. Much larger than expected probably because the locals showed steadfastness, were partially protected by Arab troops, and benefitted at the end of the day from the fatigue of an army that was by the end of 1948 too stretched and too exhausted to complete the job.

As we shall see some of the signatories wanted to rectify this by further ethnic cleansing operations, but the majority reconciled to the presence of a Palestinian minority and imposed a harsh military rule on it so as to ensure that its “rights” do not clash with the ethnic identity and ideology of the Jewish state.

Thus in many ways the proclamation was born in sin. It was drafted while Jewish forces were ethnically cleansing most of Palestine’s towns but before they had to face troops from the Arab world sent by an enraged public opinion in the region demanding its reluctant governments put an end to the onslaught that had already caused hundreds of thousands of refugees and hundreds of massacred Palestinians

In the end, the proclamation, written as if an ethnic state can be a democratic one, was the biggest exercise ever in squaring the circle on paper. It can of course be done with words. There is a Hebrew adage: “the paper tolerates anything.” The reality, however, is that even before the ink dried on the paper, up until today, the circle cannot be squared and a project such as the Jewish state is either democratic or ethnic —it cannot be both.

This article focuses on the 35 men and two women who signed this document. Most came from Eastern Europe, from cultures and countries that had no democratic tradition and from a secluded Jewish life, religious in nature, full of suspicion of the gentiles. Their presence in Palestine was also a rebellion against this form of life and therefore, by the time they signed the document, they were far more secular, more self-assertive and self-sufficient than their parents.

But they regarded all these traits as far more important than being democratic. Long before the proclamation was declared, most of them depicted the native Palestinians as a physical obstacle that had to be conquered and removed like the rocks and swamps of the land.

Three of them came from Germany and Switzerland and reflected a more genuine interest in democracy but succumbed easily to the conviction of their Eastern European counterparts that it was best to have the first democratic election after the parts of the electorate that were not Jewish were removed from the new state.

There was one American Jew among them and two Jews who were born in Palestine. The latter represented the harmonic and peaceful reality of pre-Zionist Palestine where your religion or ethnicity did not play a major role in the way you treated your neighbor or the land itself. One Arab Jew came from Yemen.

Four of the signatories, at least on paper, were not Zionists—one a member of the communist party and three of the ultra orthodox parties.

It is hard to know whether any of these signers were cognizant of the charade they were performing, and harder still to believe they were genuinely convinced they could square the circle.

I would like to look at their actions before and after the proclamation in order to examine their relationship with democracy and its values. They were invited to sign not as individuals but as representatives of the various political factions and parties in the Zionist community and therefore, even if they were quite insignificant personalities, and some of them were, they embodied the many Zionist attempts to square the circle of a Jewish democratic state.

The proclamation was hailed as a democratic document but it is only recently and with the benefit of historical hindsight that we appreciate how similar it is to another document that was proclaimed in the very same year and prepared by a similar settler colonialist community at the Southern tip of Africa. There the Afrikaner nationalist party publicized an election platform that was the basis for the apartheid legislation and official proclamation of South Africa as an apartheid state. Both settler societies believed that only a supremacist apartheid state would enable a community of white Europeans to continue the dispossession of the native population and take over what the land had to offer. The one in Palestine felt it had to disguise this ambition with a democratic window dressing and, until recently, it seemed to do the trick—but for how long?

So, how genuine was their effort to reconcile the irreconcilable and how much was it a PR exercise, aimed mainly at an international audience? Some of them did not live long enough to see what Israel became and their impact after 1948 was limited; others played a crucial role in how the state was shaped in relation to the proclamation’s promise of democracy. It is possible, with very few exceptions, to surmise what their future attitudes would be when these people were judged according to their roles in the past. These past biographies are also taken into account in this prosopographic analysis of Israel’s founding fathers and mothers.

I have not included all of them. I left out the ultra-Orthodox Jews as they were less relevant to the issue at hand, and skipped some of the less significant apparatchiks of MAPAI, the ruling Labour movement. But most of them are here.

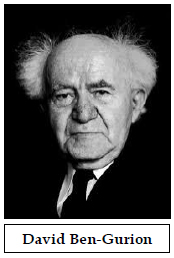

The Leader: David Ben-Gurion

If anyone epitomized, almost in a brutal way, the newspeak of the Proclamation of Independence and its impossible vision of a Jewish democracy, it was this man who led the Zionist movement to that historical moment on May 14, 1948. His name tops the list on the original document.

In many ways the past was behind him and his political future was a downhill road from the center to the periphery. But the edifice he built, in terms of his, and his movement’s geographical and demographic ambitions, was solid. The Zionist movement took over nearly eighty percent of Palestine, kicking out almost one million Palestinians and ending up with almost an exclusive majority in the new state.

From Ben Gurion’s perspective, however, Zionism in 1948 was only on solid geographical, not demographic grounds. The movement indeed took over Palestine, be it without the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, but was still in his view caught in a nightmarish demographic reality because of the presence of about 150,000 Palestinians within the Jewish State.

One should say that this phobic and hysterical vision was not fully shared by his other colleagues, although they subscribed to the same racist ideology that robbed the Palestinians of any right to their homeland and regarded their presence at best as tolerable and at worst as a potential danger. Most of the Israeli leaders could tolerate the Palestinians left inside Israel as second rate citizens. But not David Ben-Gurion; he was obsessed with the fact that the country was not free of Arabs and therefore insisted that the Palestinians inside Israel be put under military rule, one that not only robbed them of all elementary civil rights, but also incarcerated them in the places they lived in—not allowing them to move was the second best option for the ethnic cleanser of Palestine. Only after his term as a prime minister ended in 1963 was the road open for the abolition of the military rule in 1966 and its transfer a year later to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, where today it is practiced in a more sophisticated, but equally brutal, way.

His demographic paranoia informed Ben-Gurion’s ideas of democracy. That is why, while he was in office until 1963, he resisted all pressures to occupy the West Bank, and why, after 1967, he urged the government to leave the West Bank as soon as it could (apart from Jerusalem). He wanted to maintain an Israel which is disloyal to genuine democracy but can still be deemed as such by the world at large. He asserted that the charade could only be sustained as long as the Jews retain a significant majority in the state.

Ben-Gurion also wished for a less corrupt, more modest and yet predominantly European Jewish state. One assumes he would have considered the leaders who followed him did not fit the bill. Their life style was not his. Those who followed lived as super millionaires, adding personal corruption to the moral one.

And he would have welcomed the almost complete de-Arabization of the Arab Jews whom, due to his racist and orientalist view, he at first saw as Arabs; in this respect his legacy was kept and implemented.

So as our first case study, Ben-Gurion‘s actions, and those of most of his co-signatories, are the principal yardstick through which we examine the claim made in the proclamation that in 1948 a Jewish democratic state was declared and built on the ruins of Palestine. Scholars in this century tend to deconstruct texts in order to expose the real motives and viewpoints behind noble ideas when they suspect the authenticity and sincerity of the authors of these texts. In our case, we can safely say that there is no need for a complex and subtle reading of texts but rather a close scrutiny of the actions taken on the ground to cast doubt about Zionist candor when it comes to democratic values in the new state of Israel.

The Mayor: Daniel Auster

As the mayor of Jerusalem during the last days of the Mandate, Daniel Auster watched how potential Palestinian citizens of the democratic Jewish state were expelled from the Western neighborhoods of the city and the surrounding villages—including his deputy Husyan al-Khalidi who served under him in an Arab-Jewish city that, in comparison to our times, was a haven of tolerance, multiculturalism and coexistence.

Auster served once more as mayor until 1950, and in his last term in office he was particularly instrumental in erasing the memory of the Palestinians from neighbourhoods in the Western city, mainly through the destruction of buildings, renaming of streets, and the encouragement for Jewish immigrants to take over Palestinians’ homes.

Those homes were among the ones that used to host the political, cultural and financial elites of the Palestinians who now found themselves dispersed during the Nakba, the Palestinian Catastrophe of 1948.

Their descendants were able to rebuild some sort of a center during the Jordanian rule over the Eastern city, and even a Palestinian center under Israeli occupation in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the activity of Orient House under Faysal al-Husayni, as its locus.

Today that center has been totally emptied by the physical separation of East Jerusalem from the West Bank and the intensive Judaization of the Eastern parts of the city.

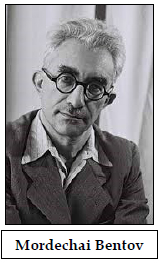

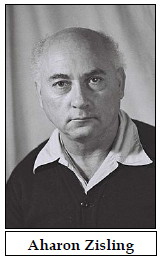

The Socialists: Mordechai Bentov, Zvi Luria, Nahum Nir Rafalkes and Aharon Zisling

These four were members of the Zionist left party Mapam, the second biggest party in the first 1949 elections.

The party had a youth movement, Hashomer Hazair, based in the Kibbutzim, and a paramilitary force, the PALMACH (acronym for storm troopers), who were the commando units of the Jewish force in 1948 Palestine, taking on a crucial role in the ethnic cleansing of the country from its native Palestinian population.

Bentov epitomized the trials and tribulations of a political movement that was hard core socialist, and at times even Stalinist, in its socioeconomic worldview.

But it became brutally nationalist when asked to practice these ideologies in the demographic reality of Palestine, where Jews were the settlers and the minority in the land.

Like so many Zionist leaders, Bentov Hebrewized his name which literally meant good money in German, Gutgeld, and turned it into good son (Ben Tov). Like Auster he was born in Eastern Europe and was one of the leaders of Hashomer Hazair in Eastern Europe. The idea that socialism could not be universal but had to be Zionist was another attempt at squaring a circle. Critical communists already noted in the beginning of the 20th century that the insistence of having a particular Jewish angle to a universalist movement was a paradoxical claim. Either you were a universalist —and believed in the equality of all workers and human beings regardless of their national, ethnic or religious identity, or you were concerned with the wellbeing of your group alone (as nationalists are). Even Zionist Jews demanding a particular Jewish angle to international socialism, the Bund, were regarded by hardcore

communists as Zionists who feared sea sickness and thus stayed in Europe and did not immigrate to Palestine. Critical sociology later on showed how socialists in the Zionist movement became more Zionist than socialist to the point where eventually their socialism was emptied of any genuine content and allowed the Israeli economy to become one of the extreme examples of capitalism in our time.

But before that happened, Bentov was leading a group of thinkers in his movement who attempted to settle some of the contradictions inherited in creating a Jewish Socialist Democratic state, by calling for the foundation of a bi-national state in Palestine.

This idea has been revived of late and seems to be more relevant after the dispossession of Palestine has been half completed and there is now a third generation of Jewish settlers on the land. Bentov tried to persuade the international community of the logic of this idea as an alternative to the Zionist mainstream insistence on partitioning Palestine. He and his friends submitted such a proposal to the Anglo-American committee of 1946, whose recommendations have long been forgotten apart from the fatal blow it dealt the Palestinian community by insisting that the fate of the Jews in Europe was closely linked to the Zionist project in Palestine. Because of that the vast majority enjoyed by the native Palestinians, which should have been the basis for a democracy in Palestine, was totally ignored by the international community that opted for an impossible partition plan that resulted in the creation of an ethnic Jewish state over much of Palestine and the ethnic cleansing of half its population.

Bentov was a low key politician after 1948 who, until his death in 1985, tried hard as a writer to square the circle of socialism and Zionism.

Aharon Zisling underwent a different trajectory before joining MAPAM. He was a veteran of one of the old kibbutzim, Ein Harod, where his family is still today.

The Kibbutz conveyed a bizarre mixture of socialist nationalism. To this day, it acts as a fortress challenging Israel’s neo-liberal economy, while at the same time it is a hotbed of hawkish nationalist ideology that envisages a greater Israel over the whole of mandatory Palestine as the only solution to the conflict.

This mixture of extreme settler colonialism with a puritan way of collective life reminds us of other settler colonies in the world where humble, modest and very tough people were at the forefront of a project which aimed at the destruction of the native population. And it always brings home a bitter truth when history is viewed from the victim’s point of view: when the boot of the settler is on the native’s face, he does not care whether the settler is carrying the bible or the book of Marx. When you are at the receiving end of the settler colonialist project aimed at your destruction, the ideological justification can hardly be of any real interest for you; your only concern is removing the boot from your face.

The President: Yitzhak Ben Zvi

Ben Zvi, the second president of Israel, was a leading figure in the Zionist movement until 1948. With such a prominent position his impact was vast on many aspects of life in the Jewish state. But when viewed from the perspective of this article, it is best to assess his impact through the activities today of the scholarly institute that carries his name, the Yad Ben Zvi Institute.

He founded the institute as an orientalist research center in 1947. After his death in 1979, its focus changed to Zionist studies. Today it publishes several of the leading academic journals in Hebrew on the history of Palestine throughout the ages. As such, it is devoted to providing the scholarly scaffolding to the Zionist narrative, an exercise much appreciated in the West until the 1980s, but one which in recent years is regarded with greater scepticism as a parochial scholarly effort at best and as pure Zionist propaganda at worst.

Ben Zvi himself, apart from his political activity, devoted much of his time to proving the same points that his institute is looking to substantiate.

The gist of this effort is to blow out of all proportion the importance of the Jewish presence in Palestine in the last two thousand years and to reduce the Palestinian community to a group of nomads with little, if any, impact on the “land without a people.” This narrative is included almost word for word in the proclamation itself.

Ben Zvi’s public activity as a president, on the other hand, showed a wish to ease the harsh conditions under which the Palestinian minority lived in Israel. And although an Eastern European Jew, like most of the other signatories, he showed an exceptional interest in the history of the Jewish communities in the Arab world, an interest reflected in the activity of the institute he founded. Today that institute divorces these Jews from their cultural environment and Arab identity and sees their immigration to Palestine as their ultimate destiny and way for salvation. This would form an important part of the de-Arabization of the Arab Jews in a way that did not benefit them socially or economically, and left them bereft of their rich cultural heritage. In reality, the impressive Jewish communities of the Arab world were reduced to marginality within the new Jewish state and had to suffer a degrading process of integration into the East European settler colonialist state found in 1948, where the main ticket to equality was proving how un-Arab they succeeded in becoming in the new state.

The Liberals: Eliahu Berlinger, Fritz Bernstein, Avraham Granovsky (Granot), Moshe Kol and Felix Rosenblüth (Pinchas Rosen)

These were the representatives of the liberal parties of Israel (as distinct from the socialist parties) who would later join forces with the Revisionists in 1977 to create the Likud. Many of their members were German Jews as were Bernstein and Rosenblüth, but there was also a significant number of central and eastern European Jews such as Kol and Granovsky.

The German Jews in the main were not very political. When they were involved in politics it was usually as avowed capitalists who succeeded in steering the economic system away from socialist principles. But apart from that they had little impact on the real issues ailing the “Jewish democracy,” namely the Palestinian question.

Bernstein was a minister of commerce and industry in several governments, which endowed him with streets named after him in various cities. His more significant work was done while he was still in Germany in the 1920s where he preached for the immigration of Jews to Palestine. Like other German Jews who were Zionists, and who did not believe in universal solutions to the problem of anti-Semitism, they found themselves in an unholy alliance with the Nazis as both wished to see the Jews leave Germany. What they helped to build instead in Palestine may have saved the Jews who left Germany like Bernstein in the 1930s, but the price paid by the native population was a bitter reminder that one cannot rectify one evil by inflicting another one.

All four had to Hebrewize their first and family names as a show of loyalty to the Zionist project. Rosenblüth, who became Rosen, founded the progressive party to which all of the four belonged at one time or another. He epitomized the German Jewish role in the charade the proclamation authored in 1948, and provided the legal framework for the settler colonialist state, disguised as a democracy. Many of his compatriots studied and practiced law in Germany before coming to Palestine and would become scholars of international repute in the field of law. Rosen himself became a minister of justice and as such did show every now and then uneasiness with the military rule imposed on the Palestinian citizens between 1948 to 1966, but it was his office, with others, that supervised this inhuman and barbaric structure that robbed the Palestinians of most of their civil and human rights.

The prime achievement of the group Rosen represented was the Israeli Supreme Court that has succeeded in being depicted domestically and internationally as the only institution of the Zionist state that is purely democratic and therefore never easily tarnished. There is, however, explicit and clear evidence that this very court has given the government its full blessing for its systematic violation of human and civil rights in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It hides behind the fact that the occupied people have the right to approach it whenever they feel their rights are being violated but, alas, on every occasion that they have done so, the court has ruled against them. Thus the court sanctioned the state’s policies of deportation, demolition of houses, confiscation of land and occasionally the assassination of civilians.

Among these four Granovsky was a veteran Zionist in Palestine. He was a Moldovan Jew who was one of the directors, and for a while chief director, of the Jewish National Fund in the 1940s. With his boss, Menachem Usishkin, he oversaw the first stages of the Zionist colonization in Palestine through the purchase of land, more often than not from absentee landlords who lived outside Palestine, and which ended with the eviction of the Palestinian tenants from their homes and livelihoods. The JNF resorted to more explicit expulsion during the 1948 war.

After the foundation of the state he became the director of Mekorot, the national water company. In his capacity both as a senior executive of the JNF and later of Mekorot, he must have known better than anyone else on the 14th of May, 1948, that equality in front of the law and equality in practice are two different matters.

The main activity of the JNF and Mekorot with regard to the native population was a systematic act of dispossessing them of land and water, without which a population that was mostly rural and lived in the countryside did not have a chance for reasonable existence no matter what the letter of the Proclamation or subsequent laws had to say about equality and democracy.

It is in his early writings back in the 1920s, when he discussed what he called land and nation, where one can see why the best and most appropriate paradigm for analyzing Zionism is settler colonialism. The mindset in the 1920s was that in order to nationalize the land you needed to de-Arabize it. The state founded in 1948 continues to adhere to this principle to this day; the means at its disposal, however, are now much more substantial and lethal and, unlike in the 1920s, funded by American taxpayer money.

Granovsky personified this desire also after 1948, overseeing the pillage of Palestinian villages and writing passionately of the need to keep them—many reduced to dust and rubble— in the hands of the Jewish nation, never to be sold or given to Arabs.

He insisted on legislation that would regulate this robbery, which led to a ceremonial purchase of the abandoned fields, villages, houses, and other properties for a ridiculous sum of money from a state custodian that waited for two years to see if anyone would reclaim them, then ruled that now they could be sold to the public. This legalistic pillage and dispossession would be at the heart of the Judaization process in the Galilee and the Negev inside Israel and of course in the settlements’ project in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This is the face of Israel’s 21st—century settler state, using the guise of democracy to legalise ethnic cleansing and dispossession.

The National Religious Group: Zeev (Wolf) Gold, Zerah Varhaftig , David Zvi Pinkas, Moshe Shapira and, Yehuda Leib Hacohen Fishman

A significant cohort of signatories came from the religious national movement, which in the pre-1948 era evolved around the movement Hapoel Hamizrahi. (Mizrahi here did not mean oriental as it would in Israel today but rather a synonym for spirituality.)

The movement they belonged to on the day of the proclamation was very different from its successor today and they themselves underwent a significant ideological transformation after 1967 from being a relatively dovish force on the local political scene to a signifier of extreme right wing messianic ideology.

The first signatory among them was Zeev Gold who was born in Russia but was educated in the United States and therefore was an important emissary, before 1948 and until his death in 1956, in recruiting the Conservative synagogues in the United State to become embassies of Israel.

Specifically, his main role was to develop Jerusalem with the help of Jewish communities in the United States. So he symbolized in many ways the role American Jews played in ridiculing the democratic values articulated in the proclamation.

The easiest targets were American Jewish communities, which probably felt that religion was not enough to identify their Judaism and American citizenship not sufficient to define their nationality. More secular and liberal Jews within the American Jewish community would notice as the years went by the impossibility of creating a democratic Jewish state.

On the other hand, a vociferous minority among them would undergo the same transformation that occurred within the religious national movement in Israel. These individuals immigrated to Israel after 1967 and became settlers in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—an import that would include Rabbi Meir Kahane, Dr. Baruch Goldstein and other less known American Jewish settlers that to this very day terrorize Palestinians in the West Bank, while the army turns a blind eye when they set fire to fields, uproot olives trees or occasionally shoot Palestinian teenagers.

This trend was already personified in the works and actions of another one of this cohort of five, Yehuda Leib Hacohen Fishman. He was a disciple of Rabbi Cook, the chief ideologue of messianic Zionism, and already demanded in 1947 the creation of a Jewish state over all of mandatory Palestine in the name of Judaism not just Zionism. At the time this was a minority view, but today it is mainstream among religious national Jews.

Moshe Shapira was a more typical representative of national religious politics before 1948. Like his counterparts in the ruling Labour (MAPAI) party, he focused on deeds and less on rhetoric. He oversaw as minister of the interior the takeover of what the Palestinians left behind them after their expulsion: bank accounts, fields, businesses, houses, books and art—the pillaged spoils of the dispossessed.

Although the life of the Palestinians inside Israel was governed by the Secret Service and less by the Ministry of Interior, its policies of discrimination and its share in the oppression indicated very early on that in practice the proclamation’s promise to guard the rights of the minority would remain on paper. It was Shapira’s office that oversaw the confiscation of land that denied the basic right Americans have, for instance to live where they want on land they own, a right that is denied until this very day by law and practice in the Jewish state.

The Communist: Meir Vilner

Vilner, the youngest and longest surviving signatory, represented the Israeli communist party and was invited to sign both because of the party’s support of the U.N. partition resolution and to maintain good relationship with the USSR. His political biography before and after 1948 exposes the complex story of the Jewish members in the Palestine Communist party that became the Israeli communist party and then split into an Arab and a Jewish one, before reuniting again under the title of the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality. His call to end the occupation and recognize the right of Palestinians to a homeland of their own alongside Israel nearly cost him his life in 1967 when a member of Herut, a right-wing political movement that evolved into today’s Likud party, tried to assassinate him.

Unlike Vilner, however, other members of the Communist party were more connected to reality after 1948 and recognized that the party became the only home, for a while, for a legitimate Palestinian political force within Israel. Palestinians were not allowed to express their national identity in pure Palestinian parties or bodies, but they could do this within a communist discourse that was regarded as less threatening by the Zionist state after 1948.

The Front today fuses the legacies of Vilner in an updated manner as a party whose main electorate is Palestinian but believes strongly in Arab-Jewish cooperation and coexistence as the only way forward and still puts its faith in human economy as the only way of dealing with the ills of the extreme capitalist system that has developed in the state.

More importantly, its parliamentary activity is still a questionable achievement in the light of how the Jewish state has progressed. The presence of Palestinians inside the Israeli Knesset still seems to beautify the racist state rather than benefit the oppressed minority.

The Revisionists: Herzel Vardi (Rosenblum) Zvi Segal and Ben Zion Sternberg

These men represented the Revisionist movement that would rule Israel after 1977 until today.

Vardi was the most significant among them. He was a Lithuanian Jew, whose claim to fame was his role as Zeev Jabotinsky’s aide in London. Jabotinsky founded the Revisionist movement that regarded not only Palestine but also Jordan as part of a future Jewish state. Vardi, which was a pen name Ben-Gurion gave Rosenblum, influenced the reality in Israel less through politics and much more through the printed media. He published the first Hebrew tabloid, Yediot Achronot, before publishing a more serious, and far more right-wing version in the daily Maariv.

He was the old guard of the revisionist party. This meant almost a fascist love for the state and its symbols, but also a kind of confidence that Jewish moral superiority and genius is so strong that he and his colleagues were far less obsessed with demographic balances between Jews and Arabs, which produced the ethnic cleansing policies of the Labour movement. Israel’s current President, Reuven Rivlin, is the last vestige of this ilk and not surprisingly, supports the idea of one state which will grant equal citizenship but is confident that these citizens, regardless of their nationality, will be content to live in a Jewish state. This form of romantic nationalism was accompanied by a disregard of international opinion and, in a bizarre way, was less threatening to the native population than the policies of Labor Zionism that did not talk the talk of destruction but did walk the walk. Israel of 2015 is run by a political elite which is a frightening mixture of both: it talks the racist talk of apartheid, ethnic cleansing and dispossession and loyally implements it through legislation and brutal policies, verging on genocide in the case of the Gaza Strip.

The “Orientals”: Saadia Kovshi

and Bechor Shitrit

In a way these were two Mizrahi Jews in the mix, but very different from one another.

Kovshi’s family came from Yemen in the early 20th century when the Eastern European Jews were looking for Arabs who were Jews to replace the cheap Arab laborers who were Muslims in the Zionist project. When they arrived, enthusiastically, as religious pilgrims, they were not allowed to live in the Eastern European Kibbutzim and were treated as Arabs who had to be separated from the European community. Their lot had improved by 1948 and Kovshi represented a Yemenite party in the Knesset and was, with Bechor Shitrit, the Mizrahi fig leaf in this Ashkenazi project of a Jewish state.

Shitrit was actually a Palestinian Jew. His family immigrated to Palestine from Morocco in the mid-nineteenth century and settled in Tiberias, where he was born. He typified what can be called the “orientalists” and not just the “orientals” of the Jewish State. He was supposed to help the Eastern European settlers decipher the alien Arab culture surrounding them, a role he assumed gladly.

One wonders whether he saw the irony that, as gratitude for his “orientalist” knowledge, he was appointed a minister of the minorities, closely associated with the ministry of police, and he held both positions. Imagine if the affairs of Hispanic, Jewish or African Americans were officially and exclusively the responsibility of Homeland Security.

Whatever aspect of life they were dealing with, the non-Jewish citizens of Israel had to take their business to the Secret Service, the police, or the Minority Ministry. They were the potential fifth column and the enemy from within, and because Bechor Shitrit was born as a Palestinian Jew who spoke Arabic he was the supreme adviser and manager of their affairs. The practices he oversaw were probably the worst violation of any promise or half-promises made in the proclamation and, in fact, they annulled any of its democratic ambitions in a very brutal and forthright manner.

The British were far more appreciative of this Palestinian Jew and appointed him to be a regional judge. But the role of judges in the new state was reserved for German Jews; Arab Jews in government were the ones entrusted with running the affairs of other Arabs.

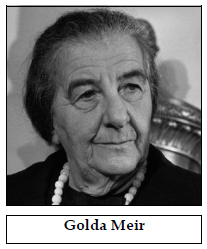

The Future Leader: Golda Meir

Golda Meir’s journey into the paradoxes that a Jewish democracy created was best illuminated in her infamous remark when she was the prime minister of Israel that there is no such thing as the Palestinian people.

She saw with her own eyes the attempt to wipe out the Palestinians from Palestine in 1948 and then, in 1972, tried to convince the world that the deed indeed had been done.

Her real disastrous actions were actually less on the Palestine front directly and more related to Israel’s relationship with Egypt.

Meir dragged Israel unnecessarily into the fiasco of the 1973 war. She was approached again and again by the Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, who suggested an Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula for either a non-aggression pact or even peace. She did not share this information with a wider circle and therefore knowingly went into the avoidable 1973 war which cost the lives of 3,000 Israeli soldiers. And in the war itself, when it was possible to end it earlier, she was looking for a photo finish on proper Egyptian soil — a pointless maneuver that cost many lives.

Later on, she would be remembered as the last Ashkenazi bastion against the unwelcomed influence on Israel of Arab, and in particular, North African Jews.

When she encountered for the first time the Black Panther movement of disenchanted, second generation Moroccan Jews in Jerusalem demanding social justice, emulating the same movement in the U.S.A., she declared “They are not nice people.”

Well, alas, many of them are still deprived socially and economically and, when they do venture into politics, it is still mostly in anti-Arab and anti-democratic movements.

The Executioner: Mordechai Shatner

Not an impressive figure but one that has to be mentioned in this context very briefly. He was a technocrat in the service of the ruling party. Two of his legacies stand out.

He was the custodian of the Palestinian refugees’ property which was sold for a pittance to the state, the Jewish National Fund and individuals. This sale was the final act in the dispossession of the Palestinians in the democratic Jewish state in the 1950s.

His second achievement was the founding of Upper Nazareth, one of many exclusive Jewish towns meant to strangulate the Palestinian citizens in the Galilee by colonizing the areas around their towns and villages and by Judaizing the space through land confiscation and pressure on Palestinians to leave.

His actions on the ground explain better than any other of the signatories’ activity why the proclamation in practice created an apartheid state inside pre-1967 Israel and why a two state solution at best would indeed end the military occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip but sanction a racist apartheid state in the rest of Palestine.

The Failed Alternative: Moshe Sharett

For many years now Moshe Sharett has symbolized the alternative to David Ben-Gurion as someone who could have steered Israel into a different direction. He did toil longer and harder than anyone else among the signatories, apart from Vilner, to balance the ethnic nature of the state with a minimal appearance of a democracy.

But he lacked Ben-Gurion’s charisma and those who met him found him quite tedious and at times boring. His dullness explains his failure to defeat Ben-Gurion in domestic politics. Even when he became prime minister for a year and a half, he was not ruling the kingdom. Ben-Gurion maintained an alternative government in Sdeh Boker, his Kibbutz in the Negev, making sure his hawkish policies that led to the Suez crisis of 1956 would govern the Jewish State.

He was the more decent among the Labor Zionists, not so much for what he had done until 1948, but because of his loyalty to the more democratic aspirations included in the proclamation of independence.

Had he played a major role, maybe this article would have had a different tone and appreciation. But his demise was the demise of any pretence and hope for democracy in the Jewish state as expressed in the proclamation of independence.

Ending the Charade

Before the Knesset dissolved itself in December 2014, three different versions of a new Nationality Law were discussed by this parliament. The three do not differ much from each other. They define Israel as a Jewish state and explicate what that means for the non-Jewish population living in the state. The law demands Jewish exclusivity in the state’s symbols, judicial systems, educational programs, overall values and identity. It does not define what is “Jewish” but it is clear that the right wing’s definition of modern day Zionism is equivalent to “Jewish.” The law has not as yet passed, but has a good chance of passing after the May 2015 elections (depending on the results of these elections).

The law is meant to deny any non-Jewish group (the Palestinians are one fifth of the population and once the West Bank, or part of it, will be annexed, their percentage will be much higher) any representation, impact or full collective rights in the Jewish State. It also adds more weight to the racist laws already passed since 2010 which discriminate against Palestinians in the state on an individual basis: land ownership, living spaces, occupational infrastructure, education, health, freedom of movement and freedom of expression; to name but few.

All three drafts refer to the Proclamation of Independence as its source of inspiration. In the spirit of this article, it is these legislators who got it right when they deemed the subtext of the proclamation as calling on the future leaders of the state of Israel to regard democracy, human and civil rights as a charade and the foundation of an ethnic, racist, Jewish state as the only reasonable and inevitable outcome of the Zionist colonization of Palestine.