| Also in this issue: In Appreciation: Rosmarie Sunderland In Appreciation: Robert V. Keeley In Appreciation: Naseer H. Aruri |

By Jonathan Cook

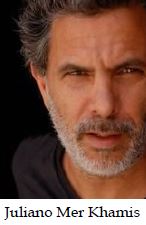

Morbid thoughts—both predictable and unexpected—fill my mind as I arrive at the Freedom Theater in Jenin’s refugee camp. The large steel gates at the entrance are familiar from the photographs that widely circulated four years ago of the spot where a masked gunman executed the theater’s founder, Juliano Mer Khamis, in broad daylight. The images show a large crowd huddled around his red Citroen car, a pool of blood by its open door. Despite much speculation, the reason he was killed is still a mystery all these years later.

Even before his death made headlines, the Freedom Theater, an arts project in the small, beleaguered Palestinian city of Jenin on the most northerly point of the West Bank, had gained an unexpected degree of international recognition. Mer Khamis had developed a program in the camp he termed “cultural resistance,” using drama and creativity to liberate young Palestinians’ minds, if not their bodies, from the heavy weight of Israel’s occupation.

The idea for the Freedom Theater—as well as an earlier incarnation, run jointly by Mer Khamis and his mother, Arna—was born in the fiery cauldron of death and suffering that was Jenin during both the first and second intifadas. The opening of the Freedom Theater in 2006 is intimately tied up with the story of the organized armed Palestinian resistance that emerged in those first years of the new millennium, and ultimately its failure against one of the most formidable armies in the world. The Freedom Theater and the concept of cultural resistance was an answer—if an inevitably incomplete one—to the questions raised by that defeat.

Jenin’s story of armed resistance echoed that of other cities in the West Bank at that time. But Jenin’s fighters burnished their military prowess more brightly than anywhere else, and as a result their fall was more rapid and tragic. They sent out young men armed with automatic rifles and bombs strapped to their chests who, for a time, blew up buses or attacked city centers in central and northern Israel. Their discipline and solidarity was such that Israel’s network of collaborators often failed to warn of an impending attack. When Israel decided to invade Jenin to put a stop to these operations, it came up against the stiffest and most creative resistance it faced anywhere in the occupied territories. The Israeli army called Jenin the “head of the cobra,” a title that the young fighters adopted as a badge of honour.

Jenin is really two small cities fused like Siamese twins. The bigger is Jenin itself, a shabby city of 45,000 people enjoying a recent revival of fortunes. Shops and restaurants have boomed in the few years since Israel loosened the siege of checkpoints that surrounded all the West Bank cities for nearly a decade and crippled their economies.

With few settlements in this area of the West Bank, Jenin has greater room to breathe than many other, larger Palestinian cities. It has benefited too from its location close to Israel and the decision a few years ago by the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, to allow Israel’s 1.5 million Palestinian citizens to once again visit and shop in the West Bank. Jenin is little more than a half-hour drive from Nazareth, the capital of Israel’s large Palestinian minority.

Next to Jenin city is its shadow, the overcrowded refugee camp, on the edge of which is to be found the Freedom Theater. The camp’s 15,000 inhabitants are the descendants of families who were expelled during the Nakba, in 1948, from their homes in what is now Israel. They upgraded their tents decades ago, and now live in densely packed cinderblock homes that have created a warren of alleys from which the Palestinian resistance waged its famous—and most successful—battle against Israel in 2002. Jenin refugee camp briefly became David to Israel’s Goliath, and looked like it might prove to Palestinians that armed resistance would win them freedom and a state.

The Battle of Jenin

It was during this period that I arrived in Nazareth. From the window where I write, I can see Jenin on a clear day across the Jezreel Valley, a greyish puddle at the foot of distant hills.

While other reporters, based in Jerusalem and Ramallah, concentrated on the intifada being waged in those cities and in nearby Bethlehem and Hebron, the intifada for me was always associated with Jenin. It was there that I had my first experience being confronted by an Israeli tank enforcing a sudden lock-down, and appreciated the quick wits of my driver who found a way through those small alleys to deliver me close to the army checkpoint on the road to Israel and my freedom.

It was there that I had dinner in the home of a teacher in the refugee camp who recalibrated my thinking about the conflict and about the importance of identity. He told me how much he pitied the Palestinians living in Israel, including my friends safely back in Nazareth, even as he and other families in Jenin were suffering from nightly curfews and Israeli incursions that killed or arrested their sons. “At least we know who we are and what we are fighting for,” he said. “Those people in Nazareth no longer have any idea who they are.”

But most of all for me Jenin was a constant journalistic challenge. It was close, its stories were urgent but so often it was unattainable. In the years before Israel erected its steel and concrete barrier to cut Jenin off from Israel and before it made access possible only through a checkpoint that now looks more like an international border crossing, reaching Jenin required ingenuity and not a little courage. It was surrounded not by a physical barrier, as it is today, but by armed Israeli units, often unseen. Venturing in when the checkpoint on the main road was closed, which it often was, meant finding a taxi driver willing to smuggle you across remote fields, and then another driver to get you out again.

At other times, I could only watch Jenin’s suffering from afar. During the notorious 12-day Battle of Jenin in April 2002, Israel sealed off the city and camp so completely that no one could make it in and only those residents being expelled—hundreds of young men—came out. The Israeli army pulled the lights on Jenin, allowing its soldiers to work through the night by sending up a constant cascade of flares so powerful that their glowing embers cast a ghostly light in my bedroom 15 miles away. On one of those nights, I slipped down a hillside to reach a village outside Jenin to hear the horror stories of those who had been expelled. Later—in a single morning of respite in which Israel allowed in humanitarian aid—I managed to smuggle myself in to witness for myself the dazed faces of Jenin’s residents emerging into the light.

When it was possible for journalists like myself to return to the camp a short time later we discovered what the Israeli army had been up to under the flares. Its giant Caterpillar bulldozers had levelled a large section of the refugee camp, where the fighters had hidden, turning it into an eerie moonscape of rubble. The camp would eventually be rebuilt but only after donors from the Gulf agreed to Israel’s humiliating condition: that the new streets be wide enough to accommodate its tanks.

Soon forgotten was the story of the armed resistance in Jenin. In the small refugee camp, Israel suffered its greatest single defeat of the second intifada. Its soldiers were lured into a trap in the heart of the camp, in which 23 were killed and dozens more wounded. It was a triumph of creative military strategy by the fighters, for which the Freedom Theater’s founder, Juliano Mer Khamis, may have had a share of responsibility.

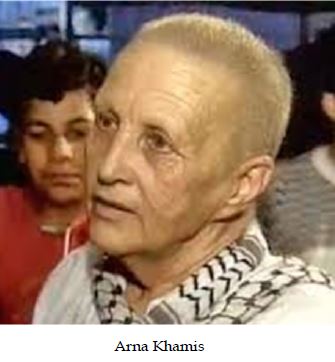

Arna’s Children

The model for the Freedom Theater was developed much earlier, when Mer Khamis’s mother, Arna, established a children’s arts project—called Learning and Freedom—in the camp during the first intifada, at the end of the 1980s. Arna was a remarkable figure. An Israeli Jew who had been a member of Israel’s elite Palmach forces in the 1948 war that dispossessed the Palestinian natives, she later crossed the ethnic lines on which the new Jewish state was premised to marry a Palestinian Christian, Saliba Khamis. Raising her three sons in Nazareth and Haifa, she started to gain a much deeper insight than most of her fellow Jewish citizens into the conundrums at the heart of a Jewish state and the outrages of the occupation.

But her defining act came during the first intifada, an uprising that took a different course from the armed intifada waged a decade later. In the period before Israel allowed the Palestinian leadership under Yasser Arafat to return to the occupied territories, the first intifada was necessarily locally led – a popular, grassroots movement that mostly adopted the principles of non-violence, at least on the Palestinian side. Men, women and children took to the streets in protest, they called general strikes, they refused to pay their taxes and boycotted the military institutions ruling over them, they threw stones and sometimes Molotov cocktails at the soldiers who entered their communities, and they refused to work in the settlements that were stealing their land.

Israel responded by drafting tens of thousands of soldiers to “restore order,” with the chief of staff Yitzhak Rabin calling for the army to “break bones.” Demolitions of homes were a common form of punishment too. The intifada ended when Israel, realizing that the occupation was becoming unmanageable, agreed to the Oslo process. Arafat was brought back to enforce the occupation on Israel’s behalf, and the international community was persuaded to underwrite the costs.

Arna began her work in Jenin at the height of Israel’s efforts to crush the rebellious spirit of the first intifada. Her attention was caught especially by the plight of the children who, after Israel closed their schools, had nowhere to go but the camp’s dangerous streets. She decided to offer them an alternative education system, using art and drama. Arna’s Children, a documentary directed by Mer Khamis, who took charge of the drama program, documents her work and its aftermath. It shows a bald-headed Arna —she was undergoing chemotherapy for cancer—and Mer Khamis helping the children to come to terms with their fears, resentment and anger through role-playing and art.

The experiment finished in the mid-1990s, as Arna succumbed to her illness and Oslo promised Palestinians a brighter future. But when those hopes crashed in 2000 with the failure of the Camp David talks and a new, more violent uprising exploded, the children Arna and Mer Khamis had tutored would discover, now as young adults, a new means of expression. It was these alumnae of Arna’s project who helped earn Jenin its reputation as the “head of the cobra.”

Two familiar faces from Arna’s Children, Nidal and Youssef Sweitat, went on to join Islamic Jihad. In 2001 they drove to the Israeli city of Hadera with their M16 automatic rifles and killed four Israeli women before being killed themselves. In a video message they made beforehand, they can be seen in front of a martyr poster for Reham Wared, a 10-year-old who died after an Israeli tank shelled her school. Youssef had gone into the rubble and pulled the girl out, watching her die in his arms as he ran to the nearby hospital.

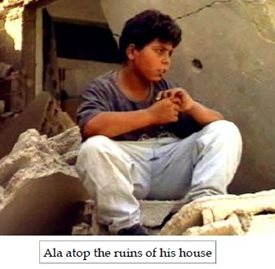

Other graduates, Ala, Ashraf and Zakaria, were among the fighters who helped briefly to vanquish the Israeli army in the Battle of Jenin. Zakaria Zubeida, whose family home hosted Arna’s project, lost his mother, Samira, to an Israeli sniper’s bullet a month before the battle. Ashraf Abu El-Haija was killed leading a group of fighters. Ala Sabagh— memorable in Arna’s Children as the 12-year-old boy sitting atop the rubble that had been his home before Israeli soldiers demolished it—would become the local head of the Al-Aqsa Brigades. In the camp’s warren of alleys he trapped the successors to the soldiers who had persecuted his family a decade earlier. After his own death six months later, when Israel fired a missile into the house in which he was sheltering, he would be succeeded by Zakaria, whose burnt face was testament to his early efforts at becoming a bomb-maker.

Descent into chaos

It is interesting to note, as one reviewer of the film has done, that Arna herself revelled in her own exploits as a young woman in the Palmach. Asked by Mer Khamis whether she was ashamed of her role in the Nakba, she answers: “Not at all.” Explaining her actions as the natural wildness of youth, she states: “I was adventurous, that’s all. I did no harm.”

The relative success of Arna’s pupils in the Battle of Jenin—if we can reduce that bloody mess to such calculations—was surely a legacy of their creativity, fearlessness and resourcefulness, qualities we might conjecture they partly discovered in Arna and Mer Khamis’s workshops. That is certainly what Arna hoped. In the film she can be seen exhorting her pupils to understand that they must know themselves to be truly free, and only when they are free can there be peace. Or as she expresses it: “There is no freedom without knowledge, and no peace without freedom.” This is at the heart of the idea of cultural resistance that shapes the Freedom Theater today.

As Arna’s Children highlights, these young fighters—apart from Zakaria, who would for many years become a shadowy fugitive in the camp—were soon dead. Most of Jenin camp’s men of fighting age were either killed alongside them or locked up in Israeli prisons. They were succeeded by the “shabab”—inexperienced teenagers—who lacked the discipline and organization of those who had landed such a harsh blow against the Israeli army.

In the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Jenin, Mer Khamis returned to the camp after an absence of several years to finish the filming for Arna’s Children. While he was there, Ala was executed. With his loss, the resistance began its slow descent into unruliness and a growing factionalism.

Mer Khamis’s relationship with Jenin was undoubtedly even more complex than his mother’s. Much earlier, aged 18, and over the stiff opposition of his parents, he had joined the occupation army for three year of mandatory military service, which included a period stationed in Jenin. His job was to carry weapons that could be planted on a woman or child if they were accidentally killed. He was dishonorably discharged after he cracked one day, punching his commanding officer in the face. And so began a new chapter of political activism.

Mer Khamis was fluent in Hebrew and Arabic, identified as a Palestinian as much as a Jew (according to the ethnic and national identities Israel imposes), and was as familiar with Palestinian codes of behavior as those in Israeli Jewish society. Nonetheless, he was invariably identified as a “Jew” by the camp’s residents in their encounters, as he shows in the film. Arna’s children may have told him that he was like an elder brother to them, but he struggled to be accepted entirely as a camp insider. Not least, he enjoyed a degree of freedom—the freedom to come and go—that he could not share with the camp’s inhabitants.

When Mer Khamis returned to complete the film, he refused to be sentimental about, or critical of, his former charges. But still a judgment of sorts creeps in. From the film, it seems clear that his idea of cultural resistance could accommodate the armed struggle of Ala, Ashraf and Zakaria, but was uncomfortable with Youssef and Nidal’s suicide operation.

Mer Khamis attaches himself to Ala and his fighters shortly before Ala’s death, his camera observing in detail the group’s constant movements to avoid being killed and their careful preparations against the Israeli soldiers who still invade the camp by night. He watches them laying booby-traps at dusk and dismantling them at dawn. There is even a firefight with an unseen enemy at night that looks, to me at least, staged—the camera lights needed to film the scene would have risked exposing the group’s precise position to the army.

Mer Khamis’s idea of cultural resistance, from what we can infer from the film, does not preclude armed resistance. It offers both an alternative to and a basis for it. Freedom, the very rationale of Arna and Mer Khamis’s theater, depends on informed choice, and therefore the boundaries between art and arms are far from clear-cut.

In another memorable scene, Mer Khamis invites an Israeli TV crew to come to Jenin to meet his students. The crew agrees, presumably lured by the chance to film the camp’s boys telling Israeli viewers how they have eschewed violence and stone-throwing for the dramatic arts. Instead Ashraf tells the camera the two are inseparable for him: “When I’m on stage I feel like I’m throwing stones. We won’t let the occupation keep us in the gutter. To me, acting is like throwing a Molotov cocktail. On stage, I feel strong, alive, proud.” It echoes Zakaria, the only one of Arna’s Children to survive, who years later explained that the Battle of Jenin—in which he evaded capture for five days by playing dead as Israeli soldiers searched amid the rubble—was the most exciting moment in his life.

But while Mer Khamis tries to avoid judging his former students for their adult decisions, Youssef’s suicide mission seems to trouble him. Mahmoud, another graduate of the drama project, chose not to join the resistance, unlike his own brothers, preferring to stay home to look after his elderly mother. Mer Khamis presses him to comment on Youssef’s decision, to offer his verdict, as a way, one cannot help but feel, to avoid directly passing judgment himself. Mahmoud observes that his friend’s suicide operation seemed like a liberation from the “prison” that is Jenin. “He felt dead. His brother was killed at home. He said, ‘I’m dead anyway. So if I have to die, I’ll choose the way.’”

It is the death of Youssef’s spirit that seems to haunt Mer Khamis. His drama project failed Youssef in a way that it did not Ala and Ashraf. Youssef’s hope, his freedom had died before he carried out his attack in Israel. Without freedom, without clarity of thought, he chose the wrong targets: not the occupation army, but four women shopping in a city center.

One wonders what factors persuaded Mer Khamis to revive his drama project as a more serious venture in 2006 and open the Freedom Theater. Was it Youssef’s suicide? Was it Ala’s heroic fight for freedom? Was it the mounting evidence that the next generation, the younger siblings of Youssef and Ala who were now leaderless, were themselves lost in a sea of uncertainty, trapped ineffectively somewhere between Ala’s heroism and Youssef’s despair?

Whatever it was, the Freedom Theater lost Mer Khamis in 2011. A gunman stepped out of a side alley, as he prepared to drive away from the theater, and shot him at close range. The killer’s motives have been much debated. Was Mer Khamis’ initiative too provocative for a conservative society like Jenin? Did Mer Khamis have money troubles or a personal feud with people in the camp? Was the killing ordered by a faction disturbed by the seeming emotional and political anarchy at the heart of the theater’s work? Or is it possible Israel used one of its collaborators against him?

By now, speculation is probably pointless. What can be said with a degree of confidence is that Mer Khamis was in part a victim of a different kind of anarchy. The organization necessary for true resistance had been demolished by Israel in the early years of the second intifada just as successfully as it had levelled the refugee camp. Israel rebuilt the camp according to its military needs; Mer Khamis was helping to rebuild the spirit of resistance as a counterpunch. While Israel appropriated the physical space of the camp’s inhabitants, Mer Khamis hoped to restore an intense emotional space for the youth, one where they might understand more clearly what resistance meant to them.

It was a battle for Jenin’s soul just as savage as the fighting in 2002. And in some ways, Mer Khamis was defeated by the assassin’s bullet, just as he was by the silence that shielded the killer. Those who survived him at the Freedom Theater have had to extract the core of his concept of cultural resistance while rethinking and adapting its principles in new ways that take account of the circumstances of his death.

The path to cultural resistance

At the Freedom Theater, I am greeted by Jonatan Stanczak, its Swedish managing director and one of the founders when the theater opened in 2006. Four years ago he was forced to step in to fill Mer Khamis’s shoes. It is hard not to be impressed by what he and the other staff have achieved in this small corner of the occupation. A former U.N. warehouse provides a large, starkly empty space where the theater productions are staged, with offices, studios, a library, kitchen and small cinema clustered around in neighboring buildings. Out of sight, behind a door, intermittent shouts, thuds and screams can be heard as eight students, from Jenin and elsewhere in the West Bank, engage in the kind of vigorous role-playing Mer Khamis encouraged. They are the most recent intake on a three-year drama course. The successors of Ala, Youssef and Zakaria.

Stanczak and the artistic director, Nabil al-Raee, have had not only to reinterpret Mer Khamis’s vision in the wake of his murder but also to reconsider the role and image of the Freedom Theater in the camp. “We thought about leaving,” admits al-Raee. “We have a responsibility to the students and their safety.” He says it took two years to get the theater back functioning as it had in Mer Khamis’s time. “We had to rebuild the bridge between us and the community.” It is an indication of the more cautious path they are treading that they have lost one of the most recent intake. A female student, the only Palestinian from inside Israel on the course, preferred to withdraw than accommodate the more conservative dress code in Jenin.

The most critical questions Stanczak and al-Raee are seeking to answer are these: What prevents Palestinians from liberating their homeland? How does Israel continue to control the Palestinian population? And why has the struggle against occupation been so unsuccessful? Their answers draw on years of discussions they shared with Mer Khamis and the theater’s other staff, as well as the lessons learned from other colonial situations, not least South Africa under apartheid.

Al-Raee observes: “Fear is a big part of the Palestinians’ reality, especially about the future. Who will take care of my dreams, do I have any choices, am I in charge of my decisions?” Stanczak concludes similarly: “From my years in Jenin it is clear that Israel controls Palestinian society by manipulating negative emotions—especially suspicion and fear—and by recruiting a network of collaborators and informers. In that way, Israel breaks down the people’s culture and undermines their identity.”

Culture, they say, is what makes us human. The problem of how to become organized and more effective was one of the earliest faced by humans. “How can 10 of us kill a mammoth?” asks Stanczak. “Individually we are too weak and too slow. We need to organize, to coordinate, to share. Culture is our shared stories, our common identity. It provides the reference map, directing how we talk and act, so that we can understand each other.”

His explanation brings to mind a comment my wife, a Palestinian from Nazareth, had made only an hour earlier, as we crossed over the checkpoint from Israel into the West Bank. As we drove into the suburbs of Jenin, she exclaimed: “It feels like we’re in Jordan.” Were she permitted to visit Gaza, it would doubtless have felt there more like Cairo. And in that simple observation may be found the problem of cultural resistance the Freedom Theater is grappling with. How does a people organize resistance, whether violent or non-violent, when it is being starved of its culture and identity? When Palestinians are slowly being turned by force of circumstance into, on one level, Jordanians, Egyptians, Lebanese, Syrians and third-class Israelis and, on another, into Jeninians, Jerusalemites, Ramallahans, Hebronites and Gazans —how can they hope to organize effectively?

Nearly 15 years ago, my dinner host in Jenin had told me how he pitied the people of Nazareth for no longer knowing who they were. Developments in the intervening years indicated that Jenin and Gaza City were no more immune from that threat.

In the Freedom Theater’s view, Palestinians suffer under four types of occupation. The best known and most visible is the Israeli occupation. But it is complemented by two other external occupations: that of the Palestinian Authority, the Palestinians’ government in waiting that has transformed itself into a security contractor for Israel, and that of the financial sector—the banks and aid agencies—that have imposed a neoliberal order and kept the Palestinians dependent on handouts. The deepest occupation of all, however, is an internal one, one that has penetrated into the soul of the occupied. It is the internalization by the oppressed of the culture and narrative of the oppressor.

Al-Raee says: “When I first met Juliano he told me, ‘Welcome to the revolution.’ Now I understand what he was talking about. We need to build fighters—those who can fight reality and oppression of all types, not just the [Israeli] occupation. Those prepared to fight for their right to exist. If you are not free in your mind, then you are not free at all. And only once we free our minds, can we start to talk about how we can win collective freedom. We are trying to build a generation that can first free themselves, then fight for the freedom of others.”

The Freedom Theater searches for an alternative to the oppressor’s imposed, corrosive culture. To deconstruct the disempowering norms of occupation, the theater encourages students to create alternative stories, based on their own experiences, and thereby gain a different perspective on and deeper understanding of the occupation. Many of the productions draw on stories told by students in the workshops. Conversely, the theater says it tries to be careful in its dealings with western arts projects and funders not to allow them to impose their own controlling assumptions and frameworks. “Not to see this as about helping ‘poor Arabs,’” as Stanczak puts it.

Cultural resistance is only one among several forms of resistance Palestinians have experimented with, including popular initiatives, various forms of boycott, and armed struggle. Stanczak calls this a “mosaic of resistance,” with the stone—the lowly weapon of David—at its very heart. “The mosaic has no pattern without it.”

The theater starts the students working with their bodies to challenge their perceptions of physical limitation. By learning that they are capable of more than they think, they begin to explore the more damaging “internal checkpoints” that limit their mind and spirit. They re-examine the internal script that subtly reflects the oppressor’s idea of them as primitive and terrorists. “If you can’t tell your own story, how can you tell another’s story? You can’t be an actor and you can’t connect to the audience,” says Al-Raee.

The biggest weakness of Palestinian society, he says, is its lack of real leaders and fighters. Israel arrests or kills Palestinian leaders, or leaves the Palestinian Authority to do the job on its behalf. The intelligence services of both are everywhere, Al-Raee notes. “Here is one place where they can feel safe – they can express themselves without being afraid that someone is watching them.” Without leaders, Palestinian society is much more vulnerable to Israel’s malign interference. Fear and suspicion weaken it and make it easy to dominate. As Nazareth film-maker Hany Abu Assad’s recent Oscar-nominated film “Omar” showed, once everyone suspects everyone else, organization is impossible – and with it hope and freedom die. A hopeless population seeks escape. Stanczak says drugs are a relatively new and increasingly serious problem in the camp, as they are now across much of the West Bank and in Jerusalem.

“The young people don’t know the difference between resistance and being gangsters,” he says. And for that reason, the Freedom Theater has continued to face bouts of the same chaotic violence—shooting attacks, a small bomb placed outside the building, and death threats—that claimed Mer Khamis’s life four years ago. “What we do is dangerous,” observes Al-Raee. “We are challenging people’s ideas, their values, their beliefs. That can be a life-changing process but it also makes you enemies.” Stanczak adds: “Who benefits from the chaos in the camp, from these small groups fighting to grab power? Israel benefits.”

The solution is to rebuild trust, recreate a sense of community and rediscover dreams. “When you’re at the bottom of a well, how can you see what is outside the well?” asks Stanczak. Letting the students create and explore emotional frictions and tensions helps them think more critically, developing a space where they can learn and reflect. “It’s the earthquake that makes you lose balance. It needs just a moment.” Behind the closed door, the students are supposed to heighten their self-awareness and develop leadership skills.

Reaching a wider audience

Unlike dabkeh, the folkloric dance that is possibly the Palestinians’ most famous artistic export, cultural resistance aspires to transcend stultifying tradition to build stories of oppression and struggle, resistance and hope. An important aspect of the Freedom Theater’s work is to take these productions around the West Bank to help nourish the soil in which a new generation of Palestinian leaders and fighters might grow.

One major project has been the Freedom Bus, bringing actors to often remote parts of the West Bank under harsh Israeli control, such as the Jordan Valley. The group specializes in “playback theater,” in which members of the audience tell of their own experiences of suffering and resistance and the actors use them to create an improvisational drama. “The innovative element of this type of theater is that the audience members speak and the actors listen,” the Freedom Bus coordinator, Ben Rivers, explained in 2012. The Freedom Bus itself challenges the movement restrictions imposed by Israel to break up the territorial continuity between Palestinian areas. “Through the Freedom Bus project, we have been able to promote contact and communication between communities and thus counter the divisive influence of the occupation.”

The Freedom Theater’s next production, due to tour the West Bank in the spring and the U.K. in the summer, concerns the five-week siege of Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity back in 2002, in the early stages of the second intifada. The drama, selected for touring because of its expected appeal to foreign audiences, is based on stories Al-Raee, who was raised in a refugee camp near Bethlehem, collected from friends and acquaintances trapped in the church. A total of 39 of the fighters who sought sanctuary in the church were expelled by Israel after their surrender, with 26 forced to Gaza, and the rest to Europe. They have not been allowed back.

It is the first time the Freedom Theater has toured in the U.K., and Al-Raee hopes it will be a way to reach British audiences and challenge their perceptions of the Palestinians—an international dimension to cultural resistance. Paradoxically, al-Raee has been denied a visa to enter Britain.

Habib Al-Raee, the stage manager, has just returned from India, where the Freedom Theater participated in Kerala’s international theater festival. Staff and actors made contacts with other cultural institutions and projects, while learning about India’s tradition of street theater. The Freedom Theater performed a South African play in English, The Island, about the lives of prisoners under apartheid. Earlier, it had been a sell-out in Jenin and other West Bank towns.

In India, the actors became ambassadors for cultural resistance. One, Ahmed Rokh, was quoted by the Hindustan Times: “The Freedom Theater is a resistance movement against occupation and injustice and we are fighters who believe in the power of our acting and camera, not guns and bombs.” While the Indian Express, under the headline “Theater of Resistance,” quoted another actor, Faisal Abu Alhayjaa: “Freedom Theater, through this play, questions why the world repeats itself in different places—South Africa, India, Palestine or elsewhere.”

A new artistic language

The Freedom Theater may be the most recognized Palestinian cultural institution internationally, but it is far from unique. Rania Jawad, a lecturer in English literature at Bir Zeit University, near Ramallah, points out that culture has long been used by Palestinians in the representation of their struggle against colonialism. In the 1970s and 1980s, under Israel’s direct occupation, culture’s role was more clandestine and informal. After their day jobs, Palestinians would meet in private homes to work on scripts and performances. Advertising was undertaken carefully to avoid attracting the military authorities’ attention. Performers were regularly arrested and shows shut down.

But following the signing of the Oslo Accords two decades ago and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA), Palestinian culture became more institutionalized. Most large towns and cities now have cultural spaces. The Jenin theater is one of 13 partner organizations in the recently established Palestinian Performing Arts Network. Most actors today aspire to being formally attached to a cultural center. The PA likes to present these cultural institutions as part of its own “modernization” and “development” agenda, even though most of the funding comes from Europe.

One long-established cultural project in the occupied territories is El-Funoun, a troupe of dozens of dancers and musicians based in Ramallah. It has been performing since the late 1970s, and, in its own words, creates “a dance saga of love, exile, estrangement and resistance.” It aims to express “the spirit of Arab-Palestinian folklore and contemporary culture through unique combinations of traditional and stylized dance and music.”

Before the PA arrived in the mid-1990s, groups like El-Funoun felt the full brunt of Israel’s efforts to destroy Palestinian culture and identity—it was illegal then even to wave a Palestinian flag. The troupe practiced and performed underground, out of view of the army. Even though El-Funoun avoided overtly political themes in this period, and was able to present its dance routines as essentially folkloric, its members were nonetheless regularly arrested and issued travel bans. Such dangers are far from over for the troupe, though now the dancers and musicians are more likely to be arrested during protests against the occupation than directly for their art.

For example, Lina Khattab, an 18-year-old dancer with El-Funoun, was sentenced in February to six months’ jail, three years’ probation and fined $1,500 after Israeli police accused her of throwing stones during a demonstration in support of Palestinian political prisoners in December 2014. She was convicted only on the word of the police. She says she has been subject to “extreme beatings” by soldiers and was tortured in prison. As part of efforts to win her release, supporters have produced a video juxtaposing her arrest with her dancing.

As if confirming Mer Khamis’s point about the intimate connection between creativity and effective resistance, one of the pivotal figures in El-Funoun has been Omar Barghouti, a choreographer. He is better known today as a founder of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, a resistance strategy Netanyahu and others accuse of “delegitimizing” Israel and that he equates with the supposed threat of a nuclear-armed Iran. The movement has advocated a cultural boycott of Israel to try to counter Israeli efforts to use culture as a weapon to brand Israel and the occupation in a more positive light. In February, 700 British artists pledged a cultural boycott of Israel.

Barghouti has observed that, on its return, the PA did little to reverse the damage inflicted on the arts by Israel, failing to promote dance, music and drama in the formal education system. He is also critical of the dominant cultural place reserved for traditional Palestinian folkloric dance like dabkeh, associated with celebratory events like weddings and olive harvests. “Such artistic experiences,” argues Barghouti, “rarely touch minds or hearts, let alone play any transformative or liberating role; they can only appease some sectors’ basic obsession with familiarity and stability—stagnation, really.”

El-Funoun has tried to reinvent the language of dance, drawing on other traditions to create a “fresh spirit, texture and movement terminology that is distinctively Palestinian in character yet universal in appeal.” Like the Freedom Theater, Barghouti speaks in terms of cultural resistance. Contemporary dance can “defy anachronistic norms, challenge patriarchic and clerical authority, or rebel against molded, inherited parameters of allowed thought and expression.” In this way, it generates enthusiasm for the arts among a new generation—or as Barghouti observes: “Being Palestinian was no longer exclusively associated in [young people’s] minds with being traditional, or being like their grandparents!”

There are other benefits. Dance can have a “critically needed, therapeutic effect on a community deeply traumatized by Israel’s relentless crimes.” In adopting a universal language, it can also act as “a vehicle through which Palestinian culture may be presented to the world in our untiring effort to counter, to refute, to substitute the myriad forms of dehumanization” imposed by the oppressor. Like the Freedom Theater, El-Funoun takes advantage of its greater, if still far from unrestricted, freedom of movement to bring its dance-stories to other Palestinians living under occupation and to audiences abroad. El-Funoun has made vigorous efforts to develop strong links with institutions and artists overseas.

The struggle for visibility

Palestinians have learned, as Arundhati Roy, the Indian writer once noted, that non-violence works best as “a piece of theater. You need an audience. What can you do when you have no audience?”

Rania Jawad notes that the conscious use of culture as a resistance strategy has long been tied to ideas of making the Palestinian cause more visible. “Palestinians are mired in a situation of extreme invisibility and visibility speaks to this need to perform. Being outside the picture describes a state of imposed invisibility.” Grand, attention-seeking strategies to end Palestinian invisibility also informed the more militant stages of Palestinian struggle in the 1960s and 1970s. “Aesthetic-political performances,” as Jawad calls them, included “the more spectacular performances of airplane hijackings and former PLO chairman Yasser Arafat’s 1974 address to the United Nations General Assembly,” his first appearance there and one in which he called on the international community to choose between an “olive branch or a freedom fighter’s gun.”

Violent forms of performance have largely failed either to win sympathy—they are usually viewed in the West simply as “terrorism”—or to advance political goals. In recent years, Palestinians have turned to cultural performance less as a way to make themselves visible than to appear “normal,” Jawad observes. “Palestinians join the ‘civilized aesthetics’ of the world as they now have orchestras and an increasing number of international and contemporary dance, literature, film, and theater festivals. Cities are populated with attractive billboards, bars, and restaurants, encouraging a culture of consumption.”

The institutionalization of culture—the effort to make it “respectable”—has flourished in the West Bank cities under the PA’s nominal control. This has not precluded “cultural resistance” as a strategy; it has simply formalized it. The Ashtar Theater in Ramallah had a significant success with its production, “The Gaza Mono-Logues,” a play based on the experiences of young Palestinians in Gaza during Israel’s attack in winter 2008-09. The play was performed widely in Gaza and the West Bank. But the company also targeted international policy-makers by securing a performance in front of the United Nations General Assembly in late 2010. When Israel barred the Palestinian youth who were to perform it from reaching New York, young actors from more than a dozen countries took their place. The publicity contributed to the play’s popularity, with it being performed in more than 50 cities around the world. Jawad concludes: “It was the very fact that Palestinians were disembodied from their stories that resulted in the global circulation of the Mono-Logues.”

But cultural resistance has possibly flourished best in places where the PA’s reach is weakest. That may not be surprising if one bears in mind the Freedom Theater’s conception of different forms of occupation. Where the PA is absent, Palestinians can confront and challenge the occupation directly. But they are also freed from the PA’s deadening hand, the impulse in its role as Israel’s security contractor to control the population as tightly as possible. The PA, like Israel, has a vested interest in preventing the emergence of a free and rebellious spirit that might turn its anger and frustrations not only on Israel but on the PA itself.

Moshe Yaalon, Israel’s defense minister, recently observed that the PA barely has control over Jenin— a claim Freedom Theater staff confirm is even truer of the refugee camp. Innovative uses of cultural resistance have also surfaced in East Jerusalem and in Area C, the nearly three-quarters of the West Bank under full Israeli civil and security control, where the PA’s presence is hardly registered.

With violent “performance,” whether the plane hijackings of the 1970s or the armed struggle of Arna’s Children 30 years later, inextricably associated in Western minds with “terrorism,” cultural resistance has preferred to identify as non-violent and tap into strategies developed by earlier, more “respectable” struggles. The civil rights movement in the U.S. in the 1960s and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa have provided useful models, especially in places like Area C where the PA does not complicate the picture.

One such initiative began in 2011 when groups of Palestinians, calling themselves “Freedom Riders,” tried to board buses in the West Bank intended only for Jewish settlers. The Freedom Riders emphasize— even with their name—an analogy with the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1960s that is intended to grab the international media’s attention. The implication is that Israel imposes on Palestinians similar policies to those of the “Jim Crow” South.

The initiative was relatively successful in terms of coverage but raised questions about the risks for Palestinians in copying the strategies of other struggles. The media mostly reported the story as one of segregation on Israeli public transport, thereby implying that the Palestinians’ primary fight was to share the West Bank with the settlers on a more equitable basis. In fact, the Freedom Riders’ protest was against the severe movement restrictions on Palestinians, restrictions designed to free Israel and the settlers to dispossess them. The specific situation faced by Palestinians—that of incremental ethnic cleansing—pertained in neither the segregated southern states of the U.S. nor in apartheid South Africa. In this case, the nature of the Palestinian liberation struggle was clouded rather than illuminated by the reference to these earlier struggles.

Over the past decade, culture has also become a conscious tool in East Jerusalem for resisting dispossession and the destruction of Palestinian identity. That struggle has become all the more acute as the PA and its political institutions have been gradually eradicated from the city. Palestinians in East Jerusalem have found themselves struggling to assert a Palestinian identity as they are sealed off by the wall from the West Bank. Notably, Israel has banned a series of cultural events in East Jerusalem, from the Palestine Literature Festival in 2009 to a children’s theater festival four years later, arguing that they are being secretly funded by the PA. Caught at the center of many of these confrontations has been East Jerusalem’s Al-Hakawati Palestinian National Theater. Its staff has been regularly harassed and questioned by the security services.

Different ideas of cultural resistance in East Jerusalem have echoed the divisions in the West Bank. In recent years cultural institutions aimed primarily at the city’s middle-class—including a music conservatoire, art gallery and cultural center—have sprung up alongside smaller, grassroots, youth-oriented initiatives. Both, however, place at their core an idea of constructing and reinforcing a Palestinian national identity as a way to stave off Israel’s attempts to dispossess and expel the local population.

Yabous, which four years ago opened as the largest cultural center in Jerusalem, shows films, stages concerts, plays and art exhibitions, and organizes writing workshops, putting an emphasis on local Palestinian and Arabic cultural production. The center’s name, Yabous, refers to the Canaanite identity of Jerusalem, before King David and the Israelites supposedly conquered the city. The name carefully conveys a sense of the population’s rootedness in the city, their prior possession, without directly alluding to Yabous as a Palestinian institution and thereby incurring the Israeli authorities’ wrath.

Yabous’s director, Suhail Khoury, has said of East Jerusalem: “The main battle is cultural.” This has been one of the criticisms of cultural resistance: that it privileges this kind of resistance over other, more important types. Projects like Yabous, in locating themselves as part of a “respectable” movement to build a Palestinian identity, risk losing sight of the fact that the Palestinians’ troubles are inherently political and need a political more than a cultural solution. And by focusing on Palestinian elites, they also risk neglecting the need for wider mobilization. This is not an oversight one can accuse Mer Khamis of making with his own brand of cultural resistance.

Nor is this point lost on the popular committees that have been working to renew a cultural life rooted in East Jerusalem’s neighborhoods. The most organized and best known was established in 2008 in Silwan, a Palestinian neighborhood just outside the Old City walls and close to the al-Aqsa mosque. Silwan is seen as a strategic area by the Israeli authorities and has become a prime target for encroachment by Jewish settlers, backed by Israel’s paramilitary police forces. While the visible battle for the Palestinian community in Silwan is against the settlers and the police, the hidden struggle is an internal one, against Palestinian informants, drug-dealers and criminals. These collaborators work hand in hand with the Israeli security services, helping the settlers to buy Palestinian homes through front companies and exposing the community’s plans for demonstrations and protests.

The committee has focused on trying to provide outlets for local youth other than crime and drugs. Its aim has been to build safe places for them away from the streets where they are likely to face off with armed police and settlers, or be prey to drugs and crime, and to build a stronger sense of community and identity to help the next generation to organize more effectively. As one Silwan activist told me: “We can’t achieve anything until we are united as a community. We need discipline to organize resistance and that is the first task we have set ourselves.”

Culture has become an essential tool in this effort, just as it has been in Jenin camp. Silwan’s community center arranges after-school programs for some 450 children, offering dance and art, as well as sports and computer skills. Here culture is being harnessed for obviously political ends.

Performance at the wall

The intimate, if often unconscious, ties between art and resistance are also apparent in the popular and largely non-violent struggles of villages in Area C of the West Bank. For years, many of them have been staging weekly protests against Israel’s construction of the wall across their land. The steel and concrete barrier is designed to deprive the villagers of use of the land, their traditional way of life, and the farming income they have relied on for generations—a “creeping annexation,” as General Moshe Dayan once described Israel’s policy in the West Bank. Bir Zeit lecturer Rania Jawad notes that these villages—such as Nabi Saleh, Budrus, Nilin and most especially Bil’in—have sought to incorporate performance into their regular confrontations with the Israeli army.

Bil’in, for example, has invited the Freedom Theater and other Palestinian groups to perform, as well as welcoming performers from abroad, including Basque nationalist musicians and a Belgian choral group. But the villagers themselves also devise moments of cultural spectacle. Such acts of resistance, Jawad observes, are not intended primarily to be artistic, but they are in part acts of theater that demand an audience. When Israel began building the wall, in 2005, the villagers chained themselves to the olive trees Israel intended to uproot. On another occasion, they locked themselves inside an iron cage to symbolize their imprisonment by the wall. To mark the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, they placed a large polystyrene wall inscribed with the words “Berlin 1989, Palestine ?” at the foot of the wall on their land. In each case, the Israeli army had to participate in the theater, and in ways designed to discomfort it. The soldiers had to cut through the villagers’ chains, to release them from their cage, and to tear down the polystyrene wall.

As Jawad concludes, “the performance of Bil‘in’s demonstrations defies the distinct separation between theater and resistance action.” She adds: “Bil‘in’s strategy of resistance is not about destabilizing our notions of what art is, but rather drawing attention to and questioning our role in the ongoing spectacle of Israeli violence against the Palestinians.”

The spectacle would be pointless without an audience. Bil’in invites international and Israeli solidarity activists to join its protests, both to perform in these acts of resistance and to serve as witnesses. But crucially, the villagers have exploited social media to enlarge their audience still further. YouTube and Facebook have built the stage on which the villagers, mostly confined to narrow areas of the West Bank, can find a way to reach an international audience with nothing more than a phone camera. Through creativity, paradox and humor, the villagers of Bilin have been able to speak to the watching world, bypassing the deadening reports of the traditional media, in an effort to assert their humanity.

The struggle has turned a few of these villagers into inspired performers, most notably for a time the imposing figure of Bassem Abu Rahma, nicknamed “Pheel,” or “Elephant” in Arabic. An iconic image shows him running along the wall flying a kite, apparently oblivious to the Israeli soldiers on the other side. It is an image of the human spirit liberated, refusing to be bowed or fearful—one that Mer Khamis doubtless appreciated. The very power of that symbolism, the small earthquake it created for the watching soldiers, may be the reason one of them decided a short time later—in April 2009—to fire a tear gas canister into Abu Rahma’s chest, killing him.

Like Mer Khamis, Abu Rahma paid a heavy price for his theater of resistance. His acts of defiance and his death were caught on camera by one of his friends, Emad Burnat. Those scenes contributed to the huge and unexpected international success of Burnat’s documentary film about his village, “5 Broken Cameras.” Through their irrepressible creativity, Abu Rahma and Mer Khamis have left an inspiring legacy that Israel has yet to find a way to crush. ■

In Memory of Bassem Abu Rahma