By Ian Lustick

With the hullabaloo surrounding Israel’s supposedly imminent “annexation” of portions of the West Bank, one might imagine that the parts of Palestine occupied in 1967 were not long ago integrated into the State of Israel. They were. Failure to internalize this one-state reality leads politicians, diplomats, activists, and non-expert observers into dangerous errors. They misread Israeli government intentions, misunderstand its rhetoric and tactics, misrepresent the dangers of “annexation,” and miss out on the real opportunities created by the predicament Israeli maximalism has created. The reality that one state dominates the entire area from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea does not mean that all zones and populations exposed to the power of the Israeli state are ruled by the same institutions or the same norms. It does mean that one state, and only one state, named Israel, upholds claims to a monopoly on violence, and determines, for all the inhabitants within the country, whose lives and property are protected and whose are not.¹

Regardless of loose and grandiose talk, no Israeli government led by Benjamin Netanyahu will ever “annex” the West Bank or impose Israeli “sovereignty” there in the sense of integrating the West Bank and its population into the State of Israel as are Tel-Aviv or the Jezreel Valley and the people, both Jews and Arabs, who live there. For Netanyahu personally, and for most of the Likud Party he leads, that would be culturally and ideologically abhorrent—a challenge to the “Jewish” nature of the state. It would also be politically suicidal for the Likud, since it would triple the number of Arab voters. Whatever Israel might do under the label of “annexation” or the banner of “sovereignty,” it will not be done to the whole of the territory of the West Bank or in a way that confers citizenship automatically on many, or even any, non-Jews.

Talk about annexation must therefore be understood in tactical, not strategic terms. Netanyahu began waving the annexation flag in September 2019, dangling prospects for it as a campaign gimmick to attract settler votes and damage the prospects of rivals to his right. Since then he has exploited Washington’s readiness to countenance ideas about annexation or implementing sovereignty to highlight his close ties with President Trump (whose popularity in Israel is higher than in any other country in the world apart from Russia and the Philippines). By doing so he burnishes his image as the only person capable of advancing Israel’s long-term ambitions to rule “Judea and Samaria” by setting precedents approved by the United States and, eventually, accepted by the world. Now in his record fifth term as prime minister, Netanyahu also wants to do something that can seem sufficiently bold and transformative to raise him within the pantheon of Zionist heroes.

To take, or to pretend to be about to take, substantively small and minimally important actions that boost one’s political fortunes, or are feted as heroic achievements, requires a triple discourse. To his right-wing base Netanyahu talks of an historic realization of Jewish rights to its ancient heartland. To settler activists who oppose the Trump Plan because it holds out even the pretense of a Palestinian state, Netanyahu promises that its details are irrelevant and that whatever expansions of official Israeli authority can be achieved today will not limit those he and his successors will be able to achieve in years to come. Meanwhile, to Israeli lawyers and a public worried about more Arabs becoming citizens, he and his surrogates are careful to refer, not to annexation or sovereignty, but to “extending Israeli law, jurisdiction, and administration” to the Jordan Valley and/or selected settlements.

This is the phrase—extending Israeli “law, jurisdiction, and administration,” that must be decoded to understand both the real dangers and real opportunities of “annexation.” The danger most often conjured, by indefatigable diplomats, diehard two-staters, and politicians looking for a reasonable sounding but safe public position on the Israel-Palestinian conflict, is that if Netanyahu’s annexation plan is implemented it will finally kill any chance for a Palestinian state or a negotiated peace agreement. Not true. As an achievable objective, rather than as a convenient slogan, the two-state solution disappeared long ago. Nothing Netanyahu does can have any effect on the prospects that, for example, a Biden administration could revive the “peace process” and bring it to a successful conclusion. But if implementing a formula to extend Israeli administration, law and jurisdiction to parts of the West Bank will not kill the two-state solution (since it is already dead), why is it dangerous?

The danger lies in the misinterpretation and mischaracterization of the pseudo-annexation Netanyahu is dangling before his supporters, and with which he taunts, goads, and distracts his opponents. Hysterical opposition to “annexation,” when permanent control of the West Bank by Israel has already been accomplished 1) prepares the ground for welcoming whatever Netanyahu does do as something which is not real annexation, and therefore justifies continued (hopeless) efforts to negotiate a two-state solution; or 2) by treating what Israel does as if it is complete annexation, surrenders opportunities to use the supposedly new status of the West Bank as grounds for demanding equal rights under Israeli law for all who live in the region.

Either way, as long as the one-state reality that has already been created by 53 years of creeping annexation is not recognized, it will not be possible to stop the Netanyahu government from using adjustments in its legal description of Israeli rule in the West Bank to advance its actual agenda—domination of rightless Palestinians within territories maximally subject to Israeli habitation and use. Opponents of “annexation” on the grounds that it forecloses chances for a negotiated peace thus become unwitting handmaidens to the institutionalization of silent apartheid. For the struggle to stop permanent incorporation of the West Bank when, from a practical point of view, it has already occurred, not only prevents recognition of that reality, but delays the launch of the eventually decisive struggles for the political equality of all those living between the river and the sea. This is the price paid by what in Israel used to be called the “peace camp,” and its international supporters, to protect a decrepit two-state solution paradigm and preserve a familiar, convenient, but increasingly embarrassing, intellectual and political orthodoxy.

Thus The New York Times editorial board condemns “annexation” because it “would render the West Bank into a patchwork of simmering, unstable Bantustans, forever threatening a new intifada.” ² Hello. That is precisely what the situation is now. Liberal Zionist groups in America, affiliated with fading but still active counterparts in Israel, such as American Friends for Peace Now, J-Street, and the New Israel Fund, oppose “unilateral annexation” because

[i]nstead of upholding the stated commitment of successive Israeli governments to resolve the status of these territories through negotiations, such a decision would say to the world that Israel wishes to systematically confer legal inferiority upon an entire population…relegating them (the Palestinians) to perpetual statelessness in isolated island-enclaves. Annexation would show, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the government of Israel no longer seeks a two-state solution. ³

It is a positive sign that this statement emphasizes the denial of political rights to Palestinians, and not just dangers posed for the two-state solution. However, it draws back from imagining a joint struggle of Jews and Palestinians for equality within the one-state that now dominates the whole land. By failing to distinguish between measures carefully designed to consolidate the systematically discriminatory effects of de facto annexation and the liberating potential of genuine, full, de jure annexation, these organizations shackle themselves to an already failed strategy and ignore the only available route for achieving the “liberal democracy” they say they favor. That long and winding road leads not through negotiations, but via political struggles to grant equal rights to all those living under the power of the Israeli state.

The metaphor of the “death” of the two-state solution has itself been beaten to death by overuse. There is little need to belabor the point. Nothing is more common in political life than the disappearance of ideas or designs for change. From 1967 to the late 1980s, both Israelis and Palestinians debated, promoted, and opposed the “Jordanian option” (according to which Israel would dispose of most or all of the West Bank and its population via an agreement with Jordan). In the early 1980s some analysts judged that it was already too late to be exercised, and that Arafat and King Hussein of Jordan had given it the “the kiss of death.”⁴ It vanished completely when the intifada prompted Jordanian “disengagement” from the West Bank in 1988. Among Palestinians, and in Israel, the two-state solution idea gained traction in its stead.

Although it is no longer available as a negotiated route to peace, it is no more true to think it was doomed from the beginning than that an arrangement between Israel and Jordan could not have been achieved, even if Golda Meir had responded positively to the “Hashemite Kingdom Plan” offered by King Hussein in 1972. When the flawed Oslo process was launched in the early 1990s there was, perhaps, a thirty percent chance a peace treaty between Israel and a West Bank/Gaza Strip State of Palestine would have resulted. But that possibility was destroyed by the timidity of the Israeli government, the ineptness of Palestinian politicians, the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, cycles of bloody violence, deliberate sabotage by the Netanyahu government, the hubris of Ehud Barak, President Clinton’s blundering diplomacy, the horrors of the second intifada, and a flood of new West Bank settlers. Now one out of 11 Israeli Jews live in the West Bank.

From an electoral point of view, the Israeli peace movement and indeed the entire liberal Zionist wing of the Israeli political spectrum, has been virtually wiped out. For the first quarter century of Israel’s existence, only the Labor Party and its allies could form governments. Between 1977 and the early 2000s, power oscillated between Labor and like-minded “centrist” parties and the right-wing Likud. But in the six elections held in Israel during the last decade, the only party capable of forming a governing coalition has been the Likud. Indeed, since at least 2009, no serious observer has been able to even imagine how an Israeli government could arise both committed to a viable two-state solution and strong enough to implement it. Israel, one can say, used to be a blue or purple state, like New Jersey or Pennsylvania. Now it is Oklahoma, Nebraska, or Idaho—deeply red.

Understanding the Difference

The one-state reality closes the door on options for ending the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip that involve cession of territory by Israel or Palestinian independence, but it opens others. Over decades and generations, Israeli institutions will inevitably be transformed by the political consequences of demographic and cultural circumstances of the one-state reality. Molding the course of that change first requires ensuring that Israeli absorption of the portions of Palestine it acquired fifty-three years ago is fully, not partially accomplished. That, in turn, means understanding the difference between sovereignty imposed in ways that open doors to political equality vs. legal and administrative measures that deepen subordination and oppression.

An example of the former, of how true annexation can lead (slowly and with much suffering and struggle) to citizenship and, eventually, to political clout for Arabs, is how Israel transformed territories conquered in 1948 (the Central and western Galilee, and the Northern Negev, and the Little Triangle–acquired by cession from Transjordan’s King Abdallah in 1950) into full parts of Israel. Until passage of Israel’s “Citizenship Law” in 1952, Israel technically had no citizens.⁵ Upon passage of the law not only all Jews, but all properly registered Arabs within the territory of the State of Israel, including in what were known as the “occupied territories,” i.e. the areas just mentioned, were to be considered citizens of the country. If that is the kind of annexation Netanyahu had in mind, it would be cause for celebration, not protest. In fact, however, we will learn much about the real meaning of what he and his cronies have planned by considering the post-1967 fate of the Arab inhabitants of expanded East Jerusalem. This will explain how Israeli politicians devoted to reaping the political, material, and ideological gains of expansionism think they can do so without paying the price of equal treatment for all those living under Israeli rule.

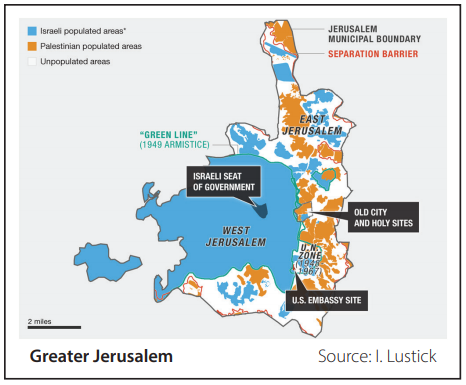

The 670,000 Israeli citizens living east of the green line (the 1949 armistice line separating the West Bank from what became the State of Israel after the 1948 war) can and do vote in Knesset elections. This is the case even though Israel does not allow absentee balloting for ordinary citizens living or travelling abroad. In other words, they are treated, as the official legal formula goes, “as if they were living in Israel.” What would change, then, if the formula of implementing “Israeli administration, law, and jurisdiction” were extended to portions of the West Bank? To answer that question, we must look closely at the result of doing just that to East Jerusalem and its nearby Arab villages when, almost immediately following the June 1967 war, the government of Israel drew a line around a 71 square kilometer area and added it to the Israeli municipality of “Yerushalayim” (i.e. West Jerusalem).

In political declarations, journalistic accounts, casual conversation, and international discussions, the complex administrative and legal maneuvers that Israel implemented in June 1967 to change the status of expanded East Jerusalem were and have been referred to as “annexation” or as effecting Israeli sovereignty over the entire city and its environs. Any lingering doubts about the effects of these moves were ostensibly eliminated in 1980 with the Knesset’s passage of the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel. The catechism contained in this law has been repeated by every Israeli government since then—that Jerusalem, “complete and united,” is Israel’s “eternal capital.”

Israel’s so-called “annexation” of East Jerusalem in 1967, the legislative decoration it added in 1980, and the construction of massive Israeli neighborhoods in the Eastern sections of the expanded municipality provoked storms of largely ineffectual international protest. But even though few countries were ready to formally acknowledge Israel’s rule of East Jerusalem, by mischaracterizing what Israel did as actual annexation, the world community allowed Israeli governments to have their cake and eat it too. The complex combination of ordinances and amendments promulgated by the Knesset and the Ministry of Interior in June 1967 very purposefully did not “annex” expanded East Jerusalem, or impose Israeli “sovereignty” there. Neither of these words (in Hebrew “Sipuach” and “Ribonut”) were used in the 1967 orders or in the 1980 law.⁶ Instead, the Interior Ministry was empowered to draw a line on the map to demarcate an area of the West Bank abutting Israeli West Jerusalem. The line was drawn to maximize land, but minimize the number of Arabs added to the city’s population. With Israeli “administration, law, and jurisdiction” applied to this area, Jewish Israelis who swiftly populated the housing projects and settlements constructed in the area could experience themselves as living within Israel (not within “Judea and Samaria”) even though the Arabs living alongside them would be treated, not as residents of the city and citizens of Israel, but only as residents of the city who by that fact became non-citizen residents of Israel. Accordingly, in the official Statistical Abstract of Israel, published annually by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, the 69,000 Arabs who lived in expanded East Jerusalem at the end of June 1967 (now grown to a population of 362,000) are counted as contributing to the size of the Arab population of Israel, but not to the voting population of the country.⁷

What is crucial to understand is that this pseudo-annexation, which is what the Netanyahu government is contemplating with respect to selected portions of the West Bank, did not and does not substantively affect the status of Jews who live there. That status is more or less exactly the status of any Israeli living in the West Bank—citizens not living in what was the State of Israel before the June war of 1967, but who are now treated as if they are living in that state. What the measure did do, however, was affect the status of non-Israelis (i.e. Palestinians) living there, transforming them into “permanent residents” of Israel but with no citizenship, no access to elections other than municipal elections, and no address for their national aspirations. For example, as a result of the peculiar way the “unification” of the city was accomplished, Israeli citizens from West Jerusalem could recover lands in East Jerusalem that they owned prior to 1948, while Palestinians living in East Jerusalem were barred from recovering their (much more extensive) properties located in West Jerusalem. Palestinians in East Jerusalem can apply for Israeli citizenship (and a few thousand have been successful in doing so), but they have no more of a legal claim to have that application accepted than a Palestinian anywhere on earth would have to apply for Israeli citizenship.

With the East Jerusalem non-annexation annexation in mind, we can see how opponents, albeit energetic and for the most part sincere, have been tilting at windmills. Win or lose in their campaign to prevent Netanyahu and Trump from issuing new proclamations, they will have helped the Israeli government distract attention from its refusal to engage with the real problem—undemocratic, discriminatory, and oppressive rule of millions of non-citizen Palestinians. This wasted effort is only an example of how opponents of the occupation, and strugglers on behalf of Palestinian rights, need to become much more sophisticated about the political dynamics at work in the one-state reality. Only then will they be able to fundamentally reassess their definition of the problem and the range of options available for addressing it. For in the world as it is, the question is not how to continue the struggle for a Palestinian state, but how to bring Israel’s silent apartheid policies of ghettoization and disenfranchisement into view so that they can be targeted in the name of an anti-occupation movement devoted to equality, democracy, and mutual rights to non-exclusivist self-determination.

The Palestinian Population of Jerusalem and the Arab Joint List

In this effort, the untapped political potential of the large Palestinian population of Jerusalem is a striking example of an opportunity waiting to be exploited. If they could vote in Israeli national elections, and assuming they would have voted at the rate and in the same general way as the 1.5 million Arab citizens of Israel did in the last election, the mostly Arab Joint List would have received 19 (instead of 15) seats in the parliament. This would not have guaranteed a change in the complexion or policies of the Israeli government that did emerge, but it would have dramatically accelerated a process already well underway by which this Arab dominated party is attracting many thousands of Jewish votes and, by so doing, establishing itself as the second largest political force in Israel (next to the Likud).

Of course, it will take time before a struggle to grant political rights to these Arab subjects of the Israeli state (those living in East Jerusalem) succeeds. Yet it cannot begin as long as the Palestinian Authority, Arab Israelis, and Jewish liberals insist that the Palestinians of East Jerusalem remain trapped in the political limbo they have inhabited for half a century, just to preserve the non-existent possibility that Israel will allow a Palestinian state to be established with al-Quds as its capital. The first move to escape this limbo will be increased Palestinian participation in Jerusalem municipal elections.

Ever since June 1967 Arabs holding Jerusalem residency cards already have had the right to vote for city councilors and for the mayor. Traditionally, however, Palestinians have boycotted municipal elections, largely because of the opposition of the PLO and now the Palestinian Authority. In 2008, 2,600 Palestinians voted (a mere 1% of eligible voters), dropping to 1,100 in 2013. But consolidation of the one-state reality has had an effect. A Palestinian poll in 2015 reported that 52% of Arabs living in East Jerusalem “would prefer to be citizens of Israel with equal rights — compared with just 42% who would opt to be citizens of a Palestinian state.”⁸ A poll of West Bank Palestinians showed that fully 58% favored the idea of East Jerusalem Palestinians voting in municipal elections. Five months before the October 2018 municipal election another poll showed that 22% of eligible Palestinians in the city did intend to vote or were thinking about voting in what was shaping up to be an extremely close election.⁹ Several Palestinian parties seeking representation on the council formed and announced campaigns, but were pressured by both Palestinian and Israeli authorities into withdrawing. One such movement remained in the raise, however, “al-Quds, Baladi,” (Jerusalem, My Hometown). Despite threats against the family of its leader, Ramadan Dabash, and the withdrawal of other candidates from its list, the party attracted 3,000 votes out of more than 4,000 votes cast in the first round of the election by residents of Arab neighborhoods.

Assuming there are approximately 280,000 Arabs eligible to vote in Jerusalem elections, that is a turnout rate of 1.4%, not high enough to make Dabash a member of the city council, but still higher than in the two previous elections. What makes this outcome significant as a harbinger of things to come is not only vastly increased discussion among Palestinians about the advisability of voting, but the exquisite narrowness of the outcome of the election. In the November runoff between the right-wing and ultranationalist candidate, Moshe Lion, and the liberal, secular oriented Ofer Berkovich, Lion won by fewer than 4,000 votes—only 0.7% of the votes cast. If only fifteen percent of those Arabs who had registered an intention to vote had actually voted that would have changed the outcome of the election, transforming the landscape of politics and policy in the Israeli capital, and dramatically demonstrating the potency of Jewish-Arab political partnerships.

Of course, the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Palestinian Authority, and Israel have a variety of options for suppressing Arab participation. But increasingly explicit coercion, threats to remove residency rights, or actions to deprive all those Palestinians living east of the separation barrier of their residency rights, have high costs and themselves testify to the lengths Palestinian and Israeli political establishments now need to go to forestall the broad-based struggles for democratization and equality incubated by the one-state reality. The PA already suffers from rock-bottom approval ratings and will have difficulty running directly against the majority opinion of Palestinians on behalf of a two-state solution plan few believe can be fulfilled. Israel has already entrenched the expanded border of the Jerusalem into a Basic Law, dooming one attempt already to use the separation barrier as the new border. Indeed one can see from the Knesset’s increasingly explicit use of discrimination against Arabs, as in the controversial new Basic Law, “Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People,” how the political potential of Arab mobilization to tip the scales of Israeli elections has incentivized the right to build higher political, legal, and ideological barriers against the democratizing dynamics of a one-state reality.

Another marker of this trend appears in Israeli policies toward the naturalization of Arab residents of East Jerusalem. Since 1967 Israeli governments have advertised opportunities for them to apply for Israeli citizenship as a way to legitimize Israeli rule of the whole city. Between 2003 and 2016, 14,629, Palestinian Jerusalemites applied for Israeli citizenship. Most of those applications were denied. Since 2013 virtually no approvals have been granted, reflecting the Israeli government’s calculation that thwarting Arab political mobilization is worth the cost of opportunities to legitimize its rule.¹°

Indeed, it has become clear to the Likud and its ultra-right-wing and clericalist allies that the effective disappearance of the Labor Party, the stark diminution of the liberal Zionist Meretz Party, and the disintegration of the Blue and White Party, the Joint List attracted tens of thousands of Jewish votes in the last 2020 election. It’s leader Ayman Odeh has very close ties to the PA and its President, Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen). Although in keeping with that alliance Odeh still supports the two-state solution, the rank and file within the groups that make up the Joint List are unenthusiastic at best and actively searching for ways to pool their resources with Palestinians across the green line to fight for equality and a better future. ¹¹

Once the one-state reality is accepted as the appropriate framework for political action, a host of potential alliances can be imagined between groups of Jews and groups of both enfranchised and unenfranchised Palestinians. Joint interests in economic prosperity, uninterrupted commerce, health and sanitation, ecology, labor, legal continuity, effective use of land and water, norms of equality and anti-discrimination, and protection against damage done by transnational boycotts, will provide the ground for numerous initiatives and cross-cutting partnerships. So too will Jewish parties move toward realizing true annexation and sovereignty by expanding suffrage and citizenship. In part this will happen as a result of the contradictions between insisting the green line no longer exists, and yet preventing Arabs living or born east of the non-existent line from crossing it to the western side. As these inhabitants of the country clamor for political rights, it will provoke anxieties among rival Jewish parties who will see relative advantages to be gained over their rivals if they do not find their own ways to compete for their support.

Shifts in Discourses and Expectations

But exploring and realizing those opportunities will entail substantial shifts in Palestinian and Israeli political discourses and expectations.

On the Palestinian side, the need is somewhat ironic. Instead of moderating their hopes, Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, in what was “Israel proper,” and in the diaspora, need to re-embrace dreams of living freely as citizens in a democratic state including all of Palestine, from the river to the sea. Instead of clinging to the idea of a small “independent” Palestinian state that would confine West Bank and Gaza Palestinians to one fifth of the country, with some sliver or edge of Jerusalem as its capital, they can plan for uniting as one community and sharing all the country, including all of Jerusalem-Al-Quds, with approximately the same number of Jews, and half a million non-Jewish non-Arabs).

This means that Palestinian politicians who have hitched their personal and political wagons to the two-state solution, and to the status and money associated with maintaining the pretense of its availability, will have to leave politics or pass away in favor of a new generation prepared to struggle for older and more ambitious goals than those the post-1967 generations were constrained to pursue. It means leading the international community from its commitment to a Palestinian state to an affirmation of the fulfillment of the legal and moral rights of Palestinians without insisting on a particular institutional framework for doing so. It means changing the time frame of strategic calculation–from years to decades and generations. This is the time it will take to trade the catastrophic problems stateless Palestinians now face for the better problems they will face in struggles to realize equal rights for all the inhabitants of the country. It means relinquishing an Algerian model for ending occupation by a climactic territorial withdrawal of Israeli authority. Occupations also end by complete absorption of conquered areas. That is the model used, over seven decades, by the Arabs of 1948, who ended the occupation of territories they inhabited that were outside the 1947 UN partition lines by fighting to achieve citizenship, end the military government, form political parties, and, now, to share actual power in a fragmented, tumultuous, and dynamic Israeli political arena.

Finally, for Palestinians, working within the one-state reality means accepting that Zionism, settler colonialist movement that it may have been, did succeed in establishing a national community of Jews in the whole of the Land of Israel, but that neither national self-determination nor sovereignty will, in Palestine, ever be securely established by only one ethnonational group.

For those on the Jewish-Zionist side who have found it difficult to imagine an acceptable future absent a state dominated by Jews, the adjustments necessary will be equally difficult and equally exciting. Pursuit of the two-state solution encouraged its Jewish supporters to use the “demographic argument”–Israel must withdraw from Arab territories to prevent Jews from having to live with too many Arabs. By conjuring the “demographic demon” the left sought to build support for withdrawal from Palestinian territories even if it reinforced anti-Arab prejudices by doing so. Many Jewish progressives have been uncomfortable making such a fundamentally racist argument, and its use never did lead to a winning coalition for the two-state solution. The one-state reality means that this distasteful argument only discourages Jews from discovering the vital social, economic, and political interests they share with Arabs, both those currently enfranchised and those who, eventually, can be enfranchised. However expedient it may have been to make the demographic argument in the past, it has become not only wrong but wholly counterproductive. Inflaming Jewish bigotry against Arabs living permanently within the domain of the Israeli state just does the work of those whose primary fear is of a pluralist democracy and whose only hope is an apartheid system based on subordination.

Again, the one-state reality does not mean ending the struggle against the occupation. It simply means ending the occupation in a different way—not by unattainable withdrawals, but by honoring Palestinian Arab rights to be full citizens in their own land, deserving of suffrage, equal representation, and equal command of national resources. Only in pursuit of such goals that serve the interests of Jews and Arabs will alliances be enabled capable of defeating Jewish ethnonationalism.

For Zionists, per se, the one-state reality has deeper implications. Keeping Zionism alive as a liberationist rather than a racist movement will mean relinquishing the statism that the founder of Revisionist Zionism, Ze’ev Jabotinsky and the Labor Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion established as hegemonic within it in the 1930s, the idea that only Jews should wield power over Jews. It means returning to liberal and socialist visions of a Jewish national home, wherein a large, prosperous, and secure Jewish community, neither dominating nor dominated, lives in the entire Land of Israel under non-parochial and non-exclusivist democratic institutions.

The disappearance of hopes for negotiating a two-state, or any form of “solution” to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict means the obsolescence of the paradigm used for decades by almost all those committed to peace, justice, and security in Palestine/the Land of Israel. This in turn requires a gestalt shift in their approach, entailing new concepts, a new time frame, and new kinds of strategies. For the one-state reality not only challenges decades of policy design and diplomatic strategy, it fundamentally invalidates the conceptual foundations of mainstream discourse surrounding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Stuck for decades in an increasingly impoverished one-state/two-state discourse, activists, politicians, diplomats, experts, and pundits have struggled to answer two basic questions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: 1) What blueprint for the future can satisfy the requirements of justice and the minimum aspirations of Jews and Palestinian Arabs? And 2) How can each side agree on, or be brought to accept, that blueprint?

The one-state reality challenges not just the answers offered to these questions, but the questions themselves, and the discourse that surrounds them. The fundamentally flawed assumption from which these debates and discussions flow is that resolution of the conflict will be achieved through a negotiated bargain between two sides, or an imposed arrangement to which the two sides acquiesce. This focuses attention on searching for a plan, two independent states, a single binational state, a system of cantons, a single state for all its citizens, a confederation, etc., that representatives of both sides accept. Will Israeli Jews, it is asked, ever accept a fully independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza? Or an Arab Prime Minister? Or equal access of Arabs and Jews to public land? Or free immigration of Palestinians as well as Jews? Will Palestinian Arabs, it is asked, ever accept resettlement of refugees outside of Palestine? Or national life without al-Quds as their capital? Or Jews living on hilltops throughout the West Bank?

But in the one-state reality the question is not whether or how Jews and Arabs will negotiate with one another to agree on a mutually acceptable arrangement. They won’t. Efforts in that direction will just produce more revolutions of a peace process merry-go-round that moves endlessly from initiative, through failed talks, to collapse, and then back to initiative. ¹² In the enlarged state of Israel, no “Jewish delegation” will sit at a table across from an “Arab delegation” and hammer out differences and reach agreements.

When a severely limited democracy such as Israel is in the predicament of ruling massive populations that have historically been excluded from political rights, outcomes are not designed or implemented according to a plan, they evolve, driven by the unintended consequences of unsuccessful or partially successful efforts to accomplish quite different futures. The United States is a flawed multi-racial democracy; but a multi-racial democracy of any kind was never the plan of its founders. Nor is it the result of negotiations between Blacks and Whites. When the Union army occupied the states of the confederacy millions of formerly enslaved blacks became part of the American political arena, with delayed but massive political consequences. Neither President Lincoln nor virtually anyone else in the North imagined that the result of the war should be a national state led, eventually, by a black President.

But the world changed. It always does. For generations, the Democratic Party enforced Jim Crow oppression, but with the great migration, two world wars, and sweeping changes in the role of the federal government in national life, some Whites discovered interests in alliances with Blacks. In the process the Democratic Party itself was transformed so that now it cannot even hope to win national elections without a massive turnout of black voters. In most industrial democracies, women were historically deprived of virtually all political rights. They gained suffrage, not because male and female representatives negotiated with one another about the terms of a transition to full citizenship for women, but because women struggled for rights and because male incumbents repeatedly feared defeat at the hands of male rivals unless they enfranchised women who would vote for them. Irish Catholics were not forcibly annexed into the United Kingdom in 1800 by a government that imagined it was building a multi-sectarian, British-Irish democracy. Nevertheless, after 80 years, that was the result. In 1949, when David Ben-Gurion authorized the vote for the minority of Arabs who managed to avoid expulsion when Israel was created, he did so largely because he wanted their votes, votes he knew the Military Government established over them would deliver. Now the Labor Party he led barely exists.

The one-state reality is not a solution, it is an unpleasant, but dynamic reality. As a point of departure, it offers the long and uncertain possibilities of political process, not the quick rewards of dramatic compromise. The path will be incremental and disjointed. Instead of implementing a blueprint for political co-habitation, Jews and Arabs determined to trade today’s problems for better ones in the future will focus on specific issues, such as building Jewish-Arab electoral alliances in Jerusalem; expanding commercial and economic intercourse throughout the country; regularizing legal protections for Jewish and Arab workers and employers; achieving equality and fairness for building, housing, and education; strengthening water, health, and sanitation systems; and enabling Joint List participation in governing coalitions. They will let their values—democracy, equality, and commitments to mutual non-exclusivist self-determination–and their interests—security, prosperity, ecological integrity, and access to all parts of the country—drive their decisions and their actions, , or any other particular constitutional architecture.

This image of an unguided process by which limited democracy transforms itself, willy-nilly, into a more inclusive political system offers no guarantees, and it promises no “end of conflict” solution in a time frame of months or even years. But once the gestalt shift to the one-state reality is adopted, there is much to see in the current state of affairs that augurs well for the future.

In torrents of campaign rhetoric, debate, and argumentations surrounding the three Israeli elections held between April of 2019 and March 2020 hardly a word was uttered or written suggesting that prospects for successful peace negotiations with the Palestinians, or opportunities to achieve a two-state solution, were at stake in any of these contests. That is a good thing, because it reflects a realization by both politicians and the public of the irrelevance of the “peace process.”

The same trend toward accepting the one-state reality is reflected in a May 2020 poll showing that more Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza (37%) favor abandoning efforts to secure a two-state solution, than support continuing that effort (36%).¹³ And late in 2019, Tel-Aviv University gave notice that it would close the Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research, established in 1992 to track the Oslo process and promote a negotiated two-state solution, as a result of a donor decision that there was no longer any point in supporting a project designed entirely to foster that outcome. That is also a step in the right direction, since it helps reorient analysts, progressives, and peacemakers toward asking questions about changing the kind of state Israel is rather than finding a path to extruding undesirable parts of it.

In May 2020, a Tel-Aviv University poll sponsored by the successor to the Steinmetz Center showed rising rates of public support for annexation. While 44% of Israeli Jews continued to support establishment of a Palestinian state, thirty-four percent were in favor of annexation with only limited or no rights granted to Arab inhabitants, while 15% favored annexation with the grant of full rights to Arabs living in the annexed territories—comparable to levels of support for the two-state solution thirty-five years ago. ¹⁴

Ayman Odeh, the dynamic leader of the Joint List, has remained publicly loyal to the two-state solution and resumption of the peace process. But the intellectuals and activists comprising the Joint List’s constituent groups and the thousands of Jews whose votes the party attracted, increasingly realize the impossibility of realizing that goal, acknowledge that the peace process has been, and would be, if continued, a distracting failure, and support and discuss liberal democratic visions of a country with wider horizons and wider opportunities for all its Arab inhabitants. ¹⁵

Odeh’s position on the issue is widely attributed to his close ties with the Palestinian Authority and its President, Mahmoud Abbas. But the PA is either on the way to collapse or to a transformation, all but explicitly, into an organization carrying out the administrative duties that Arab Departments in Israeli ministries have performed re Palestinian citizens inside the green line. Once that happens, Odeh, or his successors, will refocus their campaign for equal rights to all those living under Israeli rule, including Palestinians in expanded East Jerusalem, the rest of the West Bank, and in Gaza. A template for this approach is offered by Adalah, the Legal Center for Arab Rights in Israel, which has led an effort to apply liberal and rule-of-law norms within Israeli society to solve specific problems of Arabs inside the Green Line, in expanded East Jerusalem, in the West Bank, and in the Gaza Strip. Indeed, it was Adalah that represented 17 Palestinian local councils in their successful suit before the Supreme Court of Israel that overturned the below mentioned Regularization Law.

Closely associated with the rise of the Joint list is the sharp contrast between how polls and surveys of Israeli political opinion and voting intentions were conducted and reported in the past and how they were conducted and reported in the three elections of 2019 and 2020. In the past pollsters either ignored Arab voters or treated their preferences and turnout as irrelevant to electoral and coalition outcomes. Now, scores of polls published during election campaigns all include direct attention to the likely turnout rate of Arab voters and the tactical and strategic moves made by the Joint List and the largely Arab parties and movements comprising it. When the strength of rival blocs is assessed, the Joint List is regularly included within the “center-left” bloc instead of excluded as irrelevant, registering that the transformation of Israeli politics from a club of Zionist parties to an arena of Jewish and Arab contestation is already well underway.

In 2017, President Reuven Rivlin sent shock waves through the country when he confronted a large meeting of settler activists with a speech framed in old-fashioned liberal Jabotinskian terms. Rivlin called for Israeli sovereignty to be fully implemented in the entire country, from the river to the sea, including the grant of equal citizenship to all its inhabitants. The occasion for the President’s speech was promulgation of the “Regularization Law,” which retroactively legalized the confiscation of Palestinian private property by Israelis in West Bank settlements. In 2020 Israel’s Supreme Court vigorously upheld Rivlin’s depiction of this law as unacceptably discriminatory, voiding it mainly on the grounds that it contradicted, not international law, but Israeli constitutional principles of equality and human dignity.¹⁶ The debate over this law foreshadows countless struggles that will ensue as the reality of apartheid in territories holding masses of non-citizens collides with global human rights norms and the legal and moral commitments of Israeli democracy, however limited that democracy may be.

As absorption of the territories proceeds, and Israel does begin to see itself as a state containing more Arabs than Jews, political realignments are bound to occur. These may include alliances between Palestinians and non-Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union on behalf of equal rights for non-Jews, between ultraorthodox Jews and traditionalist Muslims on behalf of religious prerogatives, between liberal-dovish and secular Jews and ideologically and culturally similar Palestinians on behalf of citizenship for all those ruled by the Israeli government, and between Jews in the swath of territory around Gaza and the Palestinian inhabitants of that immense ghetto on behalf of peace and quiet, protection of water resources, and a renewal of economic ties.

As Israeli historian Benny Morris has predicted, many Jews will find the society that develops difficult or impossible to live in. They will emigrate.¹⁷

But new ways of imagining political community will also develop, ranging from ideas advanced in the “vision” documents of Israeli Palestinians, of Israel as a state for all its citizens, to obscure but potent notions of Palestinians and Jews linked by common ancestry to a common homeland, or of Jews, Christians, and Muslims connected as the children of Abraham.

Out of such sentiments of equality and respect for non-Jewish students, the Hebrew University humanities faculty, in 2017, cancelled the singing of Hatikvah, the Zionist hymn used as Israel’s national anthem, at graduation ceremonies.

In the long run, wrote John Meynard Keynes, we are all dead, and before any of the pretty pictures of the future we can imagine for Jews and Palestinians are realized, most of us probably will be. In this generation, it is not for us to finish the job. It falls to us instead to see the one-state reality for what it is; to explain how efforts to rescue the two-state solution are counterproductive; and to find specific ways to join Jews and Arabs in their struggles for equality, justice, peace, and security.

——————– —————–

1 For an in-depth analysis of the disappearance of the two-state solution and the crystallization of a one-state reality see Ian S. Lustick, Paradigm Lost: From Two-State Solution to One-State Reality (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

2 “Annexation Violates International Law,” New York Times, May 31, 2020.

3 Ori Nir, “APN Joins Progressive Israel Network’s Statement on Annexation” (May 18, 2020) https://peacenow.org/entry.php?id=34732#.XueI30VKiUk.

4 Nathan Raanan, “End of the Jordanian Option,” Davar, October 14, 1982.

5 Haim Margalith, “Enactment of a Nationality Law in Israel,” American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 2, no. 1 (Winter 1953) pp. 63-66. “Nationality” is a misleading translation of the Hebrew word “Ezrachut” (citizenship) which appears in the official name of law.

6 In his speech at the United Nations defending Israel’s actions in Jerusalem, and in an official letter to the General Secretary, then Foreign Minister Abba Eban denied Israel’s actions had political intent, declaring that the word “annexation” was “out of place” in considering what Israel had done.

7 The same technique was used by Israel in the Golan Heights, whose status as an extension of Israeli municipalities bordering the area is the same with respect to “Israeli law and jurisdiction,” as that of expanded East Jerusalem. In sharp contrast to its policy toward Palestinians in expanded East Jerusalem, however, Israeli governments have tried (mostly unsuccessfully) to legitimize Israeli rule of the Golan by forcing the 23,000 Syrian Druse living to accept Israeli citizenship.

8 David Pollock, “Half of Jerusalem’s Palestinians Would Prefer Israeli to Palestinian Citizenship,” August 21, 2015, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/half-of-jerusalems-palestinians-would-prefer-israeli-to-palestinian-citizen.

9 Jonathan Blake, Elizabeth M. Bartels, Shira Efron, Yitzhak Reiter, What Might Happen if Palestinians Start Voting in Jerusalem Municipal Elections? (Santa Monica: Rand, 2018) p. 24.

10 Ibid., p. 26.

11 More than twenty years ago a Labor Party leader, Uzi Baram, broached the idea of an alliance with East Jerusalem Arabs to secure a bid he wanted to make for the Jerusalem mayoralty. Menachem Klein, Jerusalem: The Contested City (London: C. Hurst, 2001) p. 188. Palestinians were not ready to respond, but Oslo was not yet dead, and the prestige of the Palestinian leadership was then much higher. See also See Akiva Eldar, “Should Palestinians Keep Boycotting Jerusalem Elections?” Al-Monitor (March 29, 2018).

12 See Ian S. Lustick, “The Peace Process Carousel: The Israel Lobby and the Failure of American Diplomacy,” The Middle East Journal (Summer 2020) Vol. 74 (forthcoming).

13 Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, “Public Opinion Poll No. (76) Press-Release,” http://pcpsr.org/en/node/811.

14 “Peace Index—May 2020,” International MA Program in Conflict Resolution and Mediation, Tel-Aviv University.

15 For thinking along these lines see Sam Bahour, “Asynchronous and Inseparable: Struggles for Rights and a Political End-Game,” (Ramallah: Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, 2016) with comments by Radi Jarai and Mohammad Daraghmeh; Abbad Yahya, “Azmi Bishara on what to do regarding Trump’s ‘Deal of the Century,’”TheNewArab (May 28, 2020) https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2020/5/28/a-plan-to-resist-trumps-deal-of-the-century.

16Judgment of the Supreme Court of Israel, Sitting as the High Court of Justice, HCJ 1308/17; HCJ 2055/17(Hebrew).

17 Gideon Levy, “Benny Morris’s Dystopian Predictions about Israel’s Future Miss the Point,” Haaretz, January 19, 2019.