By Donald Wagner

This issue of TheLink examines how, in order to subvert international law, human rights, and justice for all the parties to the conflict in the Holy Land, three “liberal” U.S. presidents and two mainstream Protestant theologians were influenced by domestic political considerations and a false theology of religious exceptionalism.

Woodrow Wilson, U.S. President, 1913 – 1921

When the Princeton University student group Black Justice League assembled at historic Nassau Hall in mid-November, 2015, it demanded former President Woodrow Wilson’s name be removed from all campus buildings and programs due to his racist legacy.

When the protest moved inside President Christopher Eisgruber’s office, the students insisted that their demands be met in a timely fashion and submitted two additional demands: the university must institute cultural competency and anti-racism training for staff and faculty, and a cultural space must be provided for black students on the Princeton campus.

The Princeton incident should be seen in the context of similar campus and city-wide protests now underway across the United States, including the broad-based movement against police brutality in Chicago and other major cities. But the Princeton protest had a unique dimension as it focused on the legacy of a prominent leader who had been president of both Princeton University and the United States. The so-called “liberal legacy” of Woodrow Wilson’s impeccable image was suddenly brought under scrutiny and, indeed, it is a significantly tarnished legacy. Wilson was, without question, a notorious advocate of racial segregation. President Eisgruber acknowledged as much by stating: “I agree with you that Woodrow Wilson was a racist. I think we need to acknowledge that as a community and be honest about that.”

This strange case of President Wilson elicits yet another dimension of his racism and flawed decision-making: his betrayal of a just solution for the indigenous Palestinian Arab majority amidst the rise of the Zionist movement. When presented in the fall of 1917 with the British request to support a draft of the Balfour Declaration, which favored the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, Wilson had to decide between political pressure from the British and Zionists and pressure from his own State Department to continue advocating for his “Fourteen Points,” especially the guarantee of self-determination to majority populations in the Ottoman territories. Moreover, as a Presbyterian, he may have been influenced by his church’s inclination to be favorably disposed to the Zionist cause.

Wilson’s initial response was to postpone the decision. There was simply too much on his plate with the pressures of World War I, various domestic disputes, and promotion of his “Fourteen Points.” The British elevated the pressure on him through his friend, Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, a committed Zionist. Brandeis received a cable from Chaim Weizmann, leader of the World Zionist Organization, asking for the United States to support a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The British Parliament had not at that point adopted the Declaration, but Balfour believed support from the United States was crucial if it was to be passed by Parliament and eventually the Allied nations.

About a month after the Weizmann telegram to Brandeis, Balfour raised the stakes with a personal visit to Washington and a face to face meeting with Brandeis. He urged Brandeis to secure a favorable decision from Wilson as time was running out. When Brandeis followed up with Wilson he was told that a decision would need to be delayed as the State Department was concerned about the unpredictability of the War and the potential for negative consequences if the pro-Zionist Balfour Declaration were to be adopted.

On September 23, 1917, the British made an official request directly to President Wilson. Despite strong opposition from the State Department, Wilson approved the Declaration, but on the condition that the decision remain confidential. Nahum Goldman, later the leader of the World Zionist Organization, said: “If it had not been for Brandeis’ influence on Wilson, who in turn influenced the British Parliament’s decision and the Allies of that era, the Balfour Declaration would probably never have been issued.”

What was the role of religion in Wilson’s decision to embrace the Balfour Declaration? There is no clear statement from Wilson on this matter but it is worth considering that he was self-defined as “the son of the manse.” His father was a Presbyterian minister and Wilson was a student of the bible, a rather conservative student at that, which may have predisposed him to favor the Zionist narrative and its exclusive claim to the land of Palestine. Former C.I.A. analyst Kathleen Christison makes the case:

For Wilson, the notion of a Jewish return to Palestine seemed a natural fulfillment of biblical prophecies, and so influential U.S. Jewish colleagues found an interested listener when they spoke to Wilson about Zionism and the hope of founding a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Few people knew anything about Arab concerns or Arab aspirations; fewer still pressed the Arab case with Wilson or anyone else in government. Wilson himself, for all his knowledge of biblical Palestine, had no inkling of its Arab history or its thirteen centuries of Muslim influence. In the years when the first momentous decisions were being made in London and Washington about the fate of their homeland, the Palestinian Arabs had no place in the developing frame of reference. (Kathleen Christison, “Perceptions of Palestine,“ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001; 26)

Wilson’s now famous statement to Zionist Leader Rabbi Stephen Wise in 1916 seems to confirm Christison’s analysis: “To think that I, a son of the manse, should be able to help restore the Holy Land to its people.”

Wilson was very much a product of his southern heritage and his era happened to be one that was undergoing a resurgent racism as a reaction to the limited gains of Reconstruction. This period was known as the “Great Retreat,” or the “Nadir.” Historian James W. Loewen places Wilson in this context as the most racist president since Andrew Johnson. Loewen writes: “If blacks were doing the same tasks as whites, such as typing letters or sorting mail, they had to be fired or placed in separate rooms or behind screens. Wilson segregated the U.S. Navy, which had previously been de-segregated…His legacy was extensive: he effectively closed the Democratic Party to African-Americans for another two decades, and parts of the federal government stayed segregated into the 1950s and beyond.” (James W. Loewen, “Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism,” New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005; 41)

Loewen’s analysis of the “Nadir,” and the white reaction to Reconstruction points out that it was nation-wide, with several counties in states such as Illinois and Wisconsin returning to enforced systemic racism, including the humiliating “sundown towns,” where blacks were forced by local laws to vacate certain cities and towns by “sundown” or face imprisonment or brutal beatings. Wilson was clearly a product of the “Nadir” and racism may have played a significant role in his disregard for justice in the case of the “brown” Palestinian people, while favoring the white Zionists of Europe.

One final note should be mentioned regarding Wilson and Palestine. In 1919, pressure from Secretary of State Lessing and others in the State Department convinced Wilson to send a commission to investigate the opinions of people living in the former Ottoman territories. The King-Crane Commission included Charles Crane, a wealthy contributor to Wilson’s campaigns, and Henry King, the President of Oberlin College, both supporters of the Zionist cause. Also included were four clergymen.

The Commission visited Turkey and most of the Arab territories of the Levant, listening to the opinions of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish leaders and their organizations. When the Commission submitted its report to the Wilson administration, it gave a devastating analysis of the Zionist project and the direction the British and French were embarking upon by implementing the Mandates and Balfour Declaration. In the course of their visits, King and Crane dropped their support for the Zionist program. The Commission itself stated that the Zionist program as it was being planned and implemented would be a “gross violation” of the principle of self-determination and of the Palestinian people’s rights, and should be modified. Under pressure from the British and the Zionists, the King-Crane report was essentially buried. If heeded, it might have averted the dispossession of the Palestinians and the violence that followed.

Harry S. Truman, U.S. President, 1945- 1953

On January 11, 1951, Harry S. Truman received the Woodrow Wilson Award, marking the 31st anniversary of the founding of the League of Nations. Truman had great admiration for Wilson, whom he called one of the five or six great presidents this country had produced.

Ironically, the celebration of the League of Nations took place at the White House, certainly a stretch of the political imagination, as Wilson had failed to secure Congressional support for the League while president. More ironically, the Wilson Foundation presented Truman with the award for his “courageous reaction to armed aggression on June 25, 1950,” when North Korea invaded South Korea. While that was a noble decision, one might wonder where Truman’s courage was in April, 1948, and thereafter, when Zionist militias committed a series of massacres and the newly established Israeli army and the Zionist militias drove 750-800,000 Palestinians into permanent exile.

Truman was similar to Wilson in another respect. He was a liberal Democrat and a politician influenced by Zionist pressure with a theological orientation that may have influenced his decision. Several analysts, including Truman biographers, argue that he was always sympathetic to the Zionist cause and was in fact a Christian Zionist. This is a false assumption and drawn from a narrow analysis of Truman’s political and religious development. Most of these analysts focus on Truman’s statements after he left office, including his “Memoirs,” which gave the impression he was consistently sympathetic to the Zionist cause. One familiar case occurred when he was honored by the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1953, and his old Jewish friend Eddie Jacobson introduced him as “the man who helped create Israel.” Truman stood up and retorted: “What do you mean ‘helped create?’ I am Cyrus!,” a reference to the Persian King who allowed the Jews to return to historic Palestine in 530 BCE.

Most scholars now see a far more complicated process behind Truman’s eventual embrace of Zionism. Christison and others note that Truman’s support of Zionism was more complex than in Wilson’s case. Like Wilson, Truman knew little about Palestine when he became president in 1945. From that moment he was lobbied heavily by the leaders of the Zionist movement, led by Rabbis Abba Silver and Stephen Wise. Prior to their efforts Truman had been deeply moved by the plight of the Jewish people during the Holocaust and the agony of Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis. His lifelong passion for the underdog may have underscored his sympathy for the Jewish people, but he did not initially give in to the rabbis when asked to support a Jewish state in Palestine. As he learned more about the situation, his thinking evolved in the direction of supporting a democracy for all the citizens of Palestine and opposing ethnic or religious states anywhere.

Once the United States supported the Partition Plan in the United Nations (November 29, 1947), chaos broke out and the violence gradually escalated across Palestine. In March, Truman questioned the wisdom of Partition and became more suspicious of the political pressure from the Zionists. His views on Palestine, however, were still fluid and gradually changed again, primarily due to pressures dictated by domestic politics, and increased U.S. dependence on Middle East oil.

In 1948, Truman found himself in a difficult presidential campaign against Thomas Dewey, governor of New York. Staff in his administration suggested he consider supporting the Zionist project, including Clark Clifford, a fellow Missourian and ardent Zionist. Two other Zionists were important in this regard, Clifford’s assistant Max Leventhal and David Niles. These three committed Zionists probably were decisive in moving Truman toward the Zionist camp. Truman then agreed that the United States would be the first country to recognize Israel, which he announced shortly after midnight on May 15, 1948, eleven seconds after Israel officially became a nation.

Another factor in Truman’s embrace of Zionism and Jewish exceptionalism was his personal style of fighting for the underdog. Truman came to resent the pressure he received from the State Department’s pro-Arab stance. Like Wilson before him, Truman’s State Department was opposed to Zionism and they were not shy about letting him know their views. Head of the Near East Bureau, Loy Henderson, informed Secretary of State George Marshall that the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish States was unworkable, “a view held by nearly every member of the Foreign Service or of the department who has worked to any appreciable extent on Near Eastern problems.” Henderson went on to add five substantive political points that spelled out why this was the case. When this advice was brought to Truman he resented the pressure from “the boys in pin striped pants,” as he called the State Department. At that point Truman decided to make up his own mind and the result was U.S. recognition of Israel.

Christison supports this view with a comment from a former desk officer in the State Department during Truman’s presidency, who asked to remain anonymous: “Truman was motivated at first by humanitarian concerns for Jewish refugees in Europe after World War II but domestic political considerations had a much greater impact on him.” (Christison, Ibid. 62). Truman’s journey was complicated but in the end Palestinians were sacrificed for domestic political considerations.

Two Liberal Christian Zionist Theologians

Today we hear from such pro-Zionist Christian evangelicals as Pat Robinson, and John Hagee. But before them there were pro-Zionist mainstream Protestant intellectuals such as Reinhold Niebuhr and Krister Stendahl.

The influential theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971) was at the height of his career during the Truman administration but his legacy continues to influence today’s theological academy, clergy, and a variety of political leaders. Martin Luther King, Jr. cited Niebuhr’s influence on numerous occasions, including his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Former President Jimmy Carter acknowledged Niebuhr’s influence as has President Barack Obama, who called Niebuhr “my favorite philosopher” and a lasting influence on my thinking.

When asked by journalist David Brooks of The New York Times about his “take-away” from Niebuhr, Obama responded: “The compelling idea that there’s serious evil in the world, and hardship and pain. And we should be humble and modest in our belief we can eliminate those things. But we shouldn’t use that as an excuse for cynicism and inaction. I take away … the sense we have to make these efforts knowing they are hard, and not swinging from naïve idealism to bitter realism.”

Niebuhr continues to be heralded as one of the most influential liberal Protestant theologians of the twentieth and now the early twenty-first centuries. He was a prolific author, seminary professor, and crusader for justice. He was also a passionate supporter of the Zionist cause and worked closely with mainline Protestant and Jewish Zionist organizations for a U.S. decision to support the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine.

With Nazi Germany occupying more European countries and news of the genocide against Jews (and others) reaching the west, Niebuhr grew increasingly impatient with those who cautioned against U.S. military involvement. In 1941, he left the respected liberal Christian journal, The Christian Century, and launched Christianity and Crisis. The first issue appeared on February 10, 1941, in which Niebuhr wrote the following: “I think it is dangerous to allow Christian religious sensitivity about the imperfections of our own society to obscure the fact that Nazi tyranny intends to annihilate the Jewish race.”

Niebuhr had embraced Zionism well before this 1941 statement. His still developing theology of Christian realism and his political ethics were part of the theological motivations for his wholehearted embrace of Zionism. As news of the Holocaust reached the United States and Nazi war crimes became clear, Niebuhr affirmed the Zionist movement’s adoption of the “Biltmore Platform” in 1942, which was to pursue nothing less than a Jewish state in Palestine as the only hope to save world Jewry. Also emerging from the Biltmore meetings was an aggressive lobbying campaign across the United States that included the establishment of two Christian organizations to work closely with the Zionist leadership: the American Palestine Committee and the Christian Council on Palestine. Both organizations received financial support from the Zionist movement.

Niebuhr was active with the Christian Council on Palestine. In 1946, the United States and England decided to appoint the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry into Palestine to investigate the issues. When hearings were held in the United States, the Commission heard from Christian and Jewish organizations. The Christian Council on Palestine had the opportunity to testify and selected the popular preacher and editor of the journal The Christian Herald, Rev. Daniel Poling, who stated: “it was God’s will, as revealed through biblical prophecy, for Palestine to belong to the Jews. And not only God,” he stressed, “but the Gallup poll supported this doctrine,” according to which three-fourths of informed Americans believed that there should be unrestricted Jewish immigration to Palestine.

When it was Niebuhr’s turn to testify, he provided a remarkably different Christian perspective. He emphasized the morally ambiguous dilemma of the Palestine question. He recognized that injustice would come to Arabs by allowing a flow of Jewish refugees to Palestine, but thought it less unjust than the universal rootlessness of the exploited Jews. Arabs had several territorial homelands, but Jews had none. For identity and security needs, Jews deserved at least one geographic center, and Palestine was the best option for these needs. Utilizing classic Zionist arguments, Niebuhr blended his “political realism” with religious and ethical exceptionalism to demonstrate the superiority of Zionist claims over any moral concern for the destiny of the Palestinians.

The ethical dilemma of Niebuhr’s position was compounded further after the Partition vote when a series of devastating events occurred. Before a single Arab army entered Palestine, Zionist militias initiated a series of massacres and eventually expelled nearly half of the 750–800,000 Palestinians who would be made refugees by the end of the fighting. Niebuhr was aware of the ethnic cleansing and chose to say absolutely nothing to oppose it. On one occasion he went so far as to support the concept of forced mass expulsion of Palestinians, often softening it by using the words “resettlement” or “transfer.” Shortly after these events he remarked: “Perhaps ex-President Hoover’s idea that there should be a large- scheme resettlement in Iraq for the Arabs (Palestinians) might be a way out.” As John Judis remarks in his book “Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict,” “It was another example of how American liberals, in the wake of the Holocaust and the urgency it lent to the Zionist case, simply abandoned their principles when it came to Palestine’s Arabs” (p. 214).

Another interesting case is Professor Krister Stendahl (1921-2008), a Swedish New Testament scholar and Harvard Divinity School professor. Having been influenced by Swedish missionaries who educated him on the plight of the Jews in Nazi Germany, he became a strong supporter of Zionism and, like Niebuhr, he viewed the state of Israel as the answer to the Holocaust. But Stendahl went beyond Niebuhr by claiming that the Jews, as God’s primary “chosen” people, are intimately tied to this particular land, the land of Palestine, to which he gives a religious value.

Stendahl was a close friend of Rabbi David Hartman, founder and president of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. Upon Stendahl’s retirement, Hartman offered him an annual appointment to teach at his Institute. During his many visits to Jerusalem, Stendahl met several Palestinian Christians, including Lutheran Pastor Rev. Mitri Raheb, Bishop Munib Younan, and Episcopal priest Rev. Naim Ateek, later Director of Sabeel, the Palestinian Liberation Theology Center in Jerusalem. These encounters had little or no impact on Stendahl’s embrace of the Zionist narrative.

On March 3, 2002, Stendahl was at his Cambridge, Massachusetts, home when a fax arrived with an International Herald Tribune article describing a Palestinian suicide bombing in Jerusalem that had killed 11 Israelis and injured over 50. As he came to the end of the article, he saw that his friend Rabbi Hartman was quoted, saying, “What nation in the world would allow itself to be intimidated and terrified as this whole population [Israel] is, where you can’t send your kid out for a pizza at night without fear he’ll be blown up?” Then came Hartman’s solution: “Let’s really let them understand what the implication of their actions is,” he said of the Palestinians. “Very simply, wipe them out. Level them.”

Stendahl was stunned by his friend’s words and immediately faxed him a handwritten letter: “Dear, dear David: How to answer?” He then pasted the text of the interview into his letter, with these anguished words: “If this is true, it puts much stress and pain on one of the most precious friendships I have been given. We will be in Sweden [phone number supplied] March 9-13. Then back in C-e [Cambridge]. Yours Krister.” (Paul Verduin, Praiseworthy Intentions, in Monica Burnett, “Zionism Through Christian Lenses,” Eugene, OR. Wipf and Stock, 2013; 159-160)

Hartman, it appears, never replied and Stendahl went to his grave without an answer.

I have singled out these two liberal pro-Zionist Protestant theologians who influenced several generations of clergy, theologians, and other leaders shaping U.S. policy on behalf of Israel. Others could be cited, including Paul van Buren, Clark Williamson, Karl and Marcus Barth, John Bright, W. F. Albright, and many scholars in the Albright School of Archaeology. Regrettably, the Christian Century should also be included, as its coverage of Israel-Palestine has been oriented toward the Zionist narratives since 2004.

Barack Obama, U.S. President, 2008 to Present

When the first African-American president began his initial term in 2008, he decided to bring more balance to U.S. policy in the Arab and Islamic world. Obama and his staff recognized that previous presidents had favored Israel to such a degree that the U.S. was losing influence in a vital area, resulting in growing Islamophobia at home and the rise of Islamic extremism in the Middle East and Africa. It was time for a U.S. president to send a different signal to these parts of the world.

Like Wilson and Truman, Obama was influenced by progressive political and theological traditions. His early career as a community organizer in Chicago sensitized him to the needs of the poor, as did his pastor at Trinity United Church of Christ, the influential black theologian, Rev. Jeremiah Wright. Despite feeling a need during his campaign to distance himself from Reverend Wright, the pastor’s liberation theology and scholarly work on Islam had an impact on the future president.

The critical event for Obama’s new signal to the Arab and Muslim world came with his June 4, 2009, speech at Cairo University, titled “On a New Beginning.” Obama was in his finest rhetorical form as he projected a tone of rapprochement: “I’ve come to Cairo to seek a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world, one based on mutual interest and mutual respect, and one based upon the truth that America and Islam are not exclusive and need not be in competition. Instead, they overlap, and share common principles — principles of justice and progress; tolerance and the dignity of all human beings.”

Later he turned to what the Middle East had been waiting for: new policies on Israel and Palestine. After acknowledging the historic suffering of the Jewish people and the Holocaust, Obama addressed the historic injustice inflicted on the Palestinian people, and concluded: “So let there be no doubt. The situation for the Palestinian people is intolerable. And America will not turn our backs on the legitimate Palestinian aspiration for dignity, opportunity, and a state of their own…The United States does not accept the legitimacy of continued Israeli settlements. This construction violates previous agreements and undermines efforts to achieve peace. It is time for these settlements to stop.”

For a moment, perhaps a month, there was cautious hope that there might be a “new beginning,” but the Arab world had been hopeful before, only to see their hopes dashed. Obama seemed to be sincere, and his staff and advisors in the State Department were supportive of the new direction. But it was not to last. Obama’s commitment to force Israel to end the settlements and negotiate an end of its occupation of Palestine and support Palestinian statehood did not sit well with the more extreme policies of Prime Minister Netanyahu, who returned to office with the most right-wing government in Israel’s history.

A bruising and intense power struggle ensued between the Obama administration, the pro-Israel lobby and Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition government. Netanyahu laid down the gauntlet shortly after Obama’s Cairo address in a speech at Bar Ilan University, where he invoked Israeli security needs and Israel’s right to all of the land as a biblical mandate. He added: “Our right to build our sovereign state here, in the land of Israel, arises from one simple fact: this is the homeland of the Jewish people, where our identity was forged. This is the land of our forefathers.” He then added what would be a non-starter for Palestinians in future negotiations: Israel is “the nation state of the Jewish people.” Netanyahu knew the Palestinians would never accept an ethno-religious “Jewish state,” but placing this as a demand would allow Netanyahu to blame the Palestinians for not negotiating with him.

This hardline Israeli position, while not new, became the deal-breaker. Within a year Obama and his envoys George Mitchell, and then John Kerry saw the negotiations die. Settlements had expanded at a record pace virtually eliminating any hope of a realistic Palestinian state. Soon the “new beginning” was over and it was business as usual, status quo politics for Israel and an intensification of the occupation and suffering for the Palestinians.

Obama decided to abandon the Palestinian cause in his second term and focused more intensely on the issue of Iran’s nuclear development. Rob Malley, the National Security Council’s senior director for the Middle East, wrote in a November 5, 2015 Washington Post editorial that for the first time in two decades, an American administration faces the reality that a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not in the cards for the remainder of a presidency.

Ten days after the editorial, Netanyahu met Obama in the White House and requested a new ten-year agreement on U.S. and Israeli military “cooperation.” This “cooperation” will cost U.S. taxpayers $50 billion. The agreement is likely to pass the pro-Israel Congress with minimal opposition. With this arrangement in place, Israel will have no motivation to change its current policies in Palestine. Palestinians will continue to lose their land to Israeli colonization; the brutal occupation will intensify; human rights abuses and violence will accelerate. There seems to be no hope at this time for a negotiated agreement and clearly the “two state solution” is totally moribund.

So Where Do We Go From Here?

When Dr. Martin Luther King was arrested and jailed for protesting the racial discrimination in Birmingham, Alabama, his colleagues smuggled into his jail cell an “Open Letter” from leading Christian and Jewish clergy published in a local newspaper. King read how they characterized him and his movement as “outside agitators” whose methods were “unwise and untimely.” As King sat in the jail that Easter weekend of April 16, 1963, he wrote a remarkable 7,000 word article that has been honored through the decades as one of the finest statements on racial justice.

In the “Letter”, King offers a passionate defense for his strategy of non-violent direct action and the urgency of the civil rights cause. These often quoted phrases summarize why he came to Birmingham: “ I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” Noting that he was invited to Birmingham by its civil rights community, he reminds them that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

Next his focus was on the white moderate religious leaders: “I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate.”

And so it is today with the struggle for justice in the Holy Land. One expects the religious right in the Jewish and Christian communities to support Israel’s extreme policies, but more troublesome is the neglect of justice by the so-called progressives, as we have seen in Presidents Wilson, Truman, and Obama and in the theologians Niebuhr and Stendahl.

Jewish theologians Marc Ellis and Mark Braverman have coined the phrases “the ecumenical deal” (Ellis) and “the fatal embrace” (Braverman) to summarize this moral malaise among the moderates. They point to the impact of the “Jewish-Christian interfaith dialogue,” which silences the call for justice among churches and synagogues and among church denominations, theologians, and politicians.

As we move toward the conclusion of this essay, we will consider five challenges or opportunities to change the discourse and begin to embrace justice rather than settle for the “ecumenical deal.”

Liberating the Mind and Heart

A passage from the book of Proverbs in the Hebrew/Christian Bible (Old Testament) is a helpful place to begin: “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” (Prov. 28:18). The ongoing violence between Israel and the Palestinians will not be resolved by pursuing the policies that have failed for a century. Israeli Jews are less secure today under the Netanyahu administration than they were fifty years ago. Meanwhile, the Palestinians are not leaving and Israel is steadily losing international support, according to BBC-World Service opinion polls. Israel’s occupation may last years, even decades, but it will end.

The Palestinians have been demanding their freedom for well over 100 years, sometimes through violent means but more often through nonviolent direct action and diplomacy. As noted above, the political “deck of cards” has been consistently stacked against them and, for the immediate future, this will continue to be the case. Israel’s power is concentrated at the upper levels of the U.S. political system, primarily with the so-called “white moderates” maintaining the present status quo. Where Israel is vulnerable in the United States and globally is at the grass roots, where change is underway on the Palestine question at a faster rate than Israel can respond.

Having just returned from an intensive Friends of Sabeel–North America and Kairos USA witness trip to Israel and the Palestinian territories, one of the most important themes I saw during approximately 30 meetings in 9 days was the need to “liberate our minds” from the Israeli occupation and Zionism. Israel’s all-pervasive military occupation with its Apartheid Wall, systems of military checkpoints, night-raids on homes, relentless land confiscation and colonization can dominate how one thinks and acts. Despite what may be the most brutal military occupation in recent history, Palestinians are struggling to keep their hearts, minds, and spirits liberated from such a depressing and humiliating reality.

We heard such spokespersons as Nabil al-Raee, the artistic director of the “Freedom Theater” in Jenin’s refugee camp, tell us: “Our number one job is to liberate the minds of the next generation.” In the West Bank village Nabi Saleh, organizer Bassem Tamimi delivered the same message, as did Dr. Abdelfattah Abusrour, Director of the Al-Rowwad Center in Bethlehem’s Aida Refugee Camp, as did Bethehem University Professor and community activist Dr. Mazin Qumsiyeh, as did Hebron’s Youth Against the Settements and Daoud Nassar of Tent of Nations; they all delivered the same message: “We must liberate our minds from the occupation.”

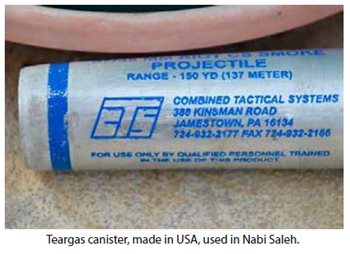

On Friday January 22nd, I witnessed women and children move to the front lines in the Nabi Saleh weekly demonstration to challenge the powerful Israeli Defense Forces with a nonviolent demonstration; here I watched them meet a barrage of teargas which, in its concentrated form, may constitute chemical warfare against unarmed civilians. The Palestinian women were joined by Israeli activists who, together, sang to the soldiers, and for a few moments the teargas and live ammunition stopped. This was “liberation of the mind” by women and children facing military might without fear.

A critical reflection on key biblical concepts

If you look back on the early history of the United States and its conquest of the western frontier and destruction of the indigenous native American Indian population, you will encounter the terms “manifest destiny” and “settler colonialism.” Settler colonialism is the political shorthand for the permanent occupation and displacement of native populations, whether in the United States and Canada, Israel, or Australia and South Africa. Manifest destiny is a concept still invoked not only by Israeli politicians, but also by Donald Trump and surprisingly Hilary Clinton in 2016.

At the heart of the concept is the familiar biblical narrative of the Hebrew tribes’ “Exodus” from Egypt and the conquest of Canaan, as recorded in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). The book of Joshua and the repetition of the conquest narrative throughout the Hebrew scriptures provides a meta-narrative that has been translated into religious and political justification for conquest movements and ethnic cleansing operations from ancient Canaan to the Crusades, North and South America, and now Palestine. Imbedded within “manifest destiny” is the theological concept of chosenness or exclusivism.

Let me be clear that the critique here is not against the Jewish religion or the Jewish people, but of the misuse of the biblical texts by Zionist ideology and its proponents. One example is how Christian hymns and spirituals in the mainline Protestant and Black churches embrace the Exodus and conquest motif with little or no critical analysis of the texts, particularly the genocide of the Canaanite population that follows in the book of Joshua. This uncritical adoption of these motifs has provided Zionism and the state of Israel with a degree of immunity thanks to unconditional support from western pulpits to the halls of Congress. It should not be surprising when we find white, liberal moderates supporting Israel’s colonization of Palestine with these same arguments. Due to space limitations I will examine only three of the numerous theological topics that need critical reflection by clergy and theologians.

Topic I: The Concept of “Exceptionalism” or Chosen People

“ Kairos-Palestine: A Moment of Truth” is a theological appeal by Palestinian Christians in December, 2009, asking the global church to respond to their suffering under the Israeli occupation. It presents the following critique of theological exceptionalism as no less than sinful: “We declare that any use of the Bible to legitimize or support political options and positions that are based on injustice, imposed by one person on another, or by one people on another, transform religion into human ideology and strip the Word of God of its holiness, its universality, and truth.” (http://www.kairospalestine.ps/content/kairos-document)

In essence, an uncritical embrace of “chosen people” as having the right to annihilate another people and seize their land, as is the case with many aspects of Christian and Jewish Zionism, is “an illegitimate use of the Bible.” To put it more succinctly, this is a false theology and a form of idolatry, as it elevates a select people above God and God’s law, even the Torah. It constitutes a sin against God and humanity.

Topic II: Ancient Israel and the Modern Zionist State of Israel

The failure of many liberal theologians, church leaders, and Jewish leaders to distinguish between the modern political state of Israel and Israel in the bible is a serious theological problem. With Israeli political leaders and their spokespersons in the pro-Israel lobby making increased use of religious claims, including the supposed continuity between Israel of the bible and the modern Zionist state, the challenge before us is an explicit decoupling of ancient Israel from the modern political state.

One of the preeminent biblical scholars of our time, Dr. Walter Brueggemann, has recently recognized the urgent nature of this problem and has become passionate about the need for a different theological analysis. He writes in his recent volume “Chosen?”: “Current Israeli leaders (seconded by the settlers) easily and readily appeal to the land tradition as though it were a justification for contemporary political ends. Nothing could be further from reality. Any and every appeal to ancient tradition must allow for immense interpretive slippage between ancient claim and contemporary appeal. To try to deny or collapse that space is illusionary.” The major schools of biblical scholarship and such journals as The Christian Century have yet to come to terms with this issue and as such, they continue to perpetuate the false claims that Professor Brueggemann is challenging.

Topic III:Justice and the “White Moderates”

The “white moderate” leadership in Birmingham’s churches and synagogues failed to grasp the demands of justice that Martin Luther King and his colleagues were pursuing in the 1960s, as did Presidents Wilson, Truman, and Obama along with theologians Niebuhr and Stendahl. The same challenge is placed at the doorstep of the white political and religious moderates today. The central theological and political issue is justice, and injustice is the great sin that continues in the so-called Holy Land and in the racially divided United States. Again, the ”Kairos-Palestine” document clearly states: “We also declare that the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land is a sin against God and humanity because it deprives the Palestinians of their basic human rights, bestowed by God. It distorts the image of God in the Israeli who has become an occupier just as it distorts this image in the Palestinian living under occupation. We declare that any theology, seemingly based on the bible or on faith or on history, that legitimizes the occupation is far from Christian teachings, because it calls for violence and holy war in the name of God Almighty, subordinating God to temporary human interests, and distorting the divine image in the human beings living under both political and theological injustice.”

The clear message of Jesus, the Hebrew Prophets, Muhammad, and the succession of our faith traditions is justice for the poor and the oppressed as the test of the nation’s or religion’s faithfulness to its creator. When asked, “What is the greatest commandment?” Jesus responded with what is the core of the Abrahamic religions: “Love God and love your neighbor as yourself.” Rabbi Brant Rosen of Jewish Voice for Peace calls us to seek “a new interfaith covenant” that will be based on equality, justice, and move us beyond all forms of tribalism and exclusivity. It will not be based on controlling interfaith dialogue as in the old “ecumenical deal,” but “finds common cause on issues of human rights in a land that holds deep religious significance” for Muslim, Christian and Jewish traditions.

Topic IV: Embracing Our Interconnectedness

According to Human Rights Watch, during Israel’s assault on the Gaza Strip in the summer of 2014, more than 2,100 Palestinians were left dead, of whom over 1,500 were civilians, including over 538 children. Another conflict was raging over 6,000 miles away in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Missouri. While a vigorous debate has ensued over the similarities and differences between the two struggles, one unmistakable reality is not debatable: young African-Americans in Ferguson began communicating with young Palestinians in Gaza, offering each other encouragement and advice.

After 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed by police in Ferguson, protests erupted between mostly black protesters and the police. Within days, Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were in touch with the Ferguson protesters via Facebook and Twitter. On August 14, Miriam Barghouti, a student at Birzeit University in the West Bank, tweeted some advice: “Solidarity with #Ferguson. Remember to not touch your face when teargassed or put water on it. Instead use milk or coke!” One minute later she followed up with: “Always make sure to run against the wind /to keep calm when teargassed, the pain will pass, don’t rub your eyes! #Ferguson Solidarity.”

Ferguson protestor #Ferguson, Joe wrote: “Thank you, man.” Anastasia Churkina, also from Ferguson sent a photo of a teargas canister with this tweet: “Central street in #Ferguson now scattered with tear gas canisters after riot police clash with protesters yet again.” Rajai Abukhalil responded from Jerusalem adding: “Dear #Ferguson. The Tear Gas used against you was probably tested on us first by Israel. No worries, Stay Strong. Love. #Palestine.” And so it was: most of the teargas used on Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza is manufactured in the United States, just as the teargas used in Ferguson is. Thousands of Facebook and Twitter exchanges went on for days, linking these two struggles for justice so distant yet not so terribly different from each other.

The above exchange is a clear case of “intersectionality,” the new buzz-word among community organizers. It was present in Dr. King’s mind when he wrote the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in 1963,: “Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states….. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”

Anna Baltzer, National Organizer for the U.S. Campaign to End the Occupation, recalled how Palestinian and Jewish activists in St. Louis began attending organizing meetings with activists from Black Lives Matter and Dream Defenders for nearly six months before they raised the issue of Palestine. The trust built over time paid off with solidarity efforts going in both directions. In January, 2015, a group of Black street organizers, activists, musicians and journalists traveled to Palestine to see the situation first hand and engage in discussions with Palestinian and Israeli activists. Journalist Mark Lamont Hill commented: “We came here to Palestine to stand in love and revolutionary struggle with our brothers and sisters. . . we stand next to people who continue to courageously struggle and resist the occupation, people who continue to dream and fight for freedom. From Ferguson to Palestine the struggle for freedom continues.”

Now the difficult challenge will be to unite these struggles until justice comes to Palestine and black America. It will be important to forge these relationships at deeper and more profound levels as time goes on. Opportunities are surfacing every week, such as the Chicago protests against police brutality and unwarranted assassinations by police. One significant issue in the “intersectionality” between Chicago and Palestine lies in the fact that many Chicago police have been trained by Israel and use Israeli “counter-terrorism” methods, employing the same brutal military combat methods the Israeli Defense Forces use on Palestinians. Other major urban areas from Boston and New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco use Israeli trainers as well. Here is an immediate opportunity for long-term organizing and solidarity in the streets, in churches, synagogues, and in the peace and justice movement.

Topic V: The Equalizer: BDS

The power imbalance in the Israeli-Palestinian struggle set the tone for Palestinian losses since the Zionist-British alliance granted Zionism its first international legitimacy. Today Israel has the full diplomatic, economic, and political support of the United States, which has helped build it into the only nuclear power in the Middle East with the strongest army, navy, and air force in the region. Since the late 1960s the United States has assured Israel that it will ensure its capacity to defeat any and all combinations of Middle East armies.

With this power imbalance in mind, the impact of the global BDS movement (boycott, divestment and sanctions) is utterly remarkable. When several visionary Palestinians established the Boycott National Committee in June, 2005, with 170 Palestinian civic organizations endorsing the original “BDS Call,” they had no idea it would grow at the present rate. Today it is the largest coalition of organizations in Palestinian civil society, representing nearly 200 organizations inside historic Palestine and in exile. With BDS movements emerging on university campuses across Europe, in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and in North and South America, today it is a global phenomenon.

After years of dismissing BDS as a “minor irritant”, Prime Minister Netanyahu and his Cabinet now recognize BDS as equal to Iran, an “existential threat” to Israel’s existence. Omar Barghouti, a founding member of the Boycott National Committee and spokesperson, commented on Israel’s failure to stop BDS: “Despair is not always easy to detect, let alone smell. But recent Israeli efforts to fight BDS smell of deep despair, which is giving rise to hopeless aggression, even worse bullying and patently irrational measures that can only help BDS to grow in the coming few years. Particularly noteworthy are reports on the Knesset’s anti-BDS caucus meeting, which convey the universal sense in Israel of failure to stem the BDS movement’s growth and the admission that the impact of BDS may be growing beyond control.”

Barghouti adds that, as Israel becomes more desperate and imposes more repressive strategies in Europe and North America, it will be perceived as undermining the basic democratic principles that the west holds dear. The next phase of Israel’s opposition to BDS will be severe, including attempts to pass legislation at the state and national levels in the United States to criminalize the movement. But Barghouti writes: “The only problem for Israel in this approach is that, in order for its attempt to legally delegitimize a nonviolent, human rights movement like BDS to succeed, it and its Zionist lobby networks need to create a new McCarthyism that defies human rights, undermines civil rights, and tries to undo decades of mainstream liberal support for boycotts as protected speech, especially in the US, where it matters the most.”

As BDS has grown in the United States, it has seen remarkable popularity on university campuses. It has also had steady growth in academic associations, and is slowly emerging in the mainline Protestant churches and some labor unions. The Presbyterian Church USA was the first to adopt divestment at its June, 2014, General Assembly, followed by the United Church of Christ in June, 2015, and the United Methodist Board of Pensions in January, 2016. The United Methodist Church, one of the largest Protestant denominations, will consider similar resolutions in May, 2016, as will other denominations.

Toward a Global Intifada

It may be fitting to conclude this essay with the challenge Bassem Tamimi of the Palestinian village Nabi Saleh put before our recent delegation in Palestine on January 22, 2016. As we sat in his living room with several Palestinian and Israeli activists after the Friday demonstration, Bassem cited the remarkable growth and power of the BDS movement and added: “What we need now is a global intifada.” He reflected on how he had been part of the violent Second Intifada, but now is passionately committed to a nonviolent struggle to end Israel’s occupation. He believes that the struggle Palestinians are carrying out inside Israel will grow, and nonviolent resistance is what Israel cannot control, particularly if it is global. “What we need now is for you in the international community to elevate your pressure through BDS and other grass roots campaigns, while we do the same on the inside.”

As I witnessed courageous farmers, villagers, Palestinians in refugee camps, students and others, I observed a remarkable resilience and commitment to popular resistance (mostly nonviolent, perhaps with the exception of youths throwing stones). Yes, it is still too early to call this a global intifada, but the present task now is to “grow” the vanguard of the global movement, BDS, into a well organized series of campaigns in churches, on university campuses, among young Jews and Muslims, to gradually empower a grassroots movement for political and religious change that cannot be ignored by the gate-keepers in Congress, the church hierarchy who resist BDS, and the business community.

While there are many signs of change in all of these venues, the next phase will be difficult as Zionist control mechanisms have considerable power at the upper levels of political and economic institutions. But they are extremely vulnerable at the grassroots levels.

This is precisely where we must intensify our efforts.

Don Wagner may be contacted at: dwag42@gmail.com.