| Also in this issue: In Appreciation: Donald Neff, 1930-2015 |

By Fred Jerome

“Kill Bernadotte” is a story enfolding several stories, beginning during the last years of World War II and continuing through into the 1947-48 war in Palestine. Time and space do not permit a discussion here of the history of Zionism from the late 19th century, the Zionist attempts at collaboration with a variety of colonialist powers from Cecil Rhodes to the Turks, French and Russians—none of which worked until the British Balfour Declaration in 1917—and the next quarter century of Palestine as a British “Mandate” (a post World-War I term for colony).

Our focus will be on one man.

The White Buses

On Sept. 18, 2008, Miriam Akavia, a Polish-born Israeli writer and her husband Hanan, both 81 years old, boarded a bus in Tel Aviv to travel to Jerusalem to attend a small memorial service in honor of Swedish Count Folke Bernadotte. Miriam and Hanan were both teenage Holocaust survivors, having somehow endured the horrors of Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz, weighing barely 50 pounds each upon their freedom, a release accredited largely to the work of Count Bernadotte.

As head of the Swedish Red Cross during World War II, Bernadotte succeeded in arranging the release of an estimated 20,000-plus prisoners from Nazi concentration camps during the last year of the war. Of those released between March and May 1945, some 11,000 were Jews who were saved through the intercession of Count Bernadotte—that according to Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum. Two of those saved were Miriam and Hanan Akavia, who otherwise almost certainly would have been sent to the gas chambers. Little wonder, then, that for the Akavias and thousands of others Bernadotte was—and would always be—a savior.1

But the story takes a bizarre twist. In 1948, Bernadotte, having been sent by the United Nations to Jerusalem to try to negotiate a settlement between the battling Arabs and Jews, was ambushed and machine-gunned to death by the Stern Gang, a Zionist terrorist organization that considered him and the U.N. anti-Jewish and a threat to Israel. The assassination took place on Sept. 17, 1948, sixty years before the memorial meeting in the Jerusalem Y.M.C.A.

The story made headlines around the world. [See The New York Times of Sept. 18th: BERNADOTTE SLAIN IN JERUSALEM; KILLERS CALLED ‘JEWISH IRREGULARS’; SECURITY COUNCIL WILL ACT TODAY.] Despite that, few people today know Bernadotte’s name, testimony to the ability of Israel, the U.S., even Sweden to bury the atrocity as soon as possible. As Sir Brian Urquhart, who would become Undersecretary-General of the world body, put it: a “conspiracy of silence” was thrown like a blanket over the assassination. Not one of the assassins was charged with the crime; the United Nations Organization (as it was then called) imposed no real sanctions against the Jewish state; and world leaders got the message: they could thumb their noses at the young organization with impunity. As David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, said of the world body, “UNO schmuno.”2

”Schmuno” or not—in response to Israel’s sham “investigation” where not one of Bernadotte’s killers, all of whom were known and walking the streets, was even arrested, let alone tried—the United Nations Organization instituted an unprecedented suit (we would call it a “civil suit”) against Israel before the International Court of Justice, arguing that Israel should pay the U.N. for its failure to protect Bernadotte or to arrest and convict the assassins. On April 11, 1949, barely six months after the murder, the Court ruled in favor of the U.N. and, while refusing “to admit error,” Israel paid the financial penalties on June 14, 1950.3 The total amount Israel paid to the U.N.O. came to barely six figures—twice the annual salaries of Bernadotte and the U.N. observer killed with him—a miniscule amount to pay for murder, especially considering the billions of dollars in annual “aid” the U.S. now sends to Israel. Indeed, such a penny-ante penalty would transform murder into a misdemeanor in almost any court in the world.

Still, the story of the assassination has been told and retold in the nearly seven decades since it was front-page news. Several books—notably but certainly not only A Death in Jerusalem by Kati Marton—give page after page of details including the names of the killers. The story is also available to Googlers. What I have tried to do here is focus on the untold and little known pieces of the “Kill Bernadotte” story.

The central figure in the story, Count Folke Bernadotte, the victim of the assassination by the Stern Gang, was born in Stockholm in 1895, grandson to Sweden’s King Gustav II. Folke spent a comfortable, if uneventful, youth surrounded by a European royal family declining in political power—not untypical for that period.

If one is looking for some genetic or family trait to “explain” Count Bernadotte’s later role as a trouble-maker—at least to the Zionists—perhaps one might point to the fact that his father, King Oscar’s second son, married a woman outside the “royal lineage” and thus, according to the ironclad Rules of Royalty, gave up his right to succession to the throne. Even Bernadotte’s marriage to the American Estelle Romain-Manville, heiress to the Johns-Manville millions, fit in with the Marry-a-European-Title that had become fashionable among rich Americans at the turn of the 20th century. But it would be a stretch to call these “rebellious family traits.” Essentially, there was nothing extraordinary in Folke Bernadotte’s early life to signal he would become a thorn in the side of the Zionists, a thorn that the Stern Gang decided to remove.

The learning point, if not the turning point in Folke Bernadotte’s life was his September 1943 appointment—at the age of 48—to head the Swedish Red Cross. As Allied victories throughout 1944 left little doubt about the final defeat of Nazi Germany, the neutral Swedish leaders felt it was time to move their “neutrality” closer to the Allies. Thus, Bernadotte—with the active support of other key Scandinavian political figures, including Niels Ditleff, the Norwegian diplomat, and Trygve Lie, soon to become U.N. Secretary General—met four times in Germany with the Nazis’ number-two man, SS-head Heinrich Himmler, to seek the immediate release of as many prisoners as possible from Nazi concentration camps.

In exchange for releasing the prisoners, what Himmler wanted was a separate peace with the Western Allies so the Nazis could intensify their war against the Russians. How much Trygve Lie and others involved behind the scenes in the discussions may have encouraged Himmler is open to question. It seems clear from his notes that Bernadotte repeatedly told Himmler the Western leaders would not agree to such a plan, but he did agree to pass the Nazi’s proposal on to President Truman and British Prime Minister Churchill. That was as close as Himmler would get to the separate peace deal. The U.S. and U.K. were not about to cut themselves off from the Russians at that point. Still, given Himmler’s desperate situation, he probably felt he had nothing to lose by sending the message. It wasn’t long before Himmler committed suicide.

But before he did, even as Allied bombing missions increased, Himmler may have held half a hope for such a separate peace—which could well explain his acceptance of Bernadotte’s “White Buses Rescue Mission.” He agreed to allow Bernadotte to organize a prisoner pick-up at German concentration camps. The rescue operation would include: 36 hospital buses, 19 trucks, 7 cars, 7 motorcycles, a tow truck, and a field kitchen. All the vehicles were painted entirely white, to be clearly visible from the air, except for the red cross on the side of each vehicle.

Between March 12 and May 8, 1945 (VE Day), the White Buses carried the 20,000-plus released prisoners to freedom in Sweden. These included some 8,000 Norwegians and Danes; 2,629 French; 1,124 Germans; and more than 6,000 Poles, mostly Polish Jews liberated from camps.

Among the Polish Jews were Miriam and Hanan Akavia.

Miriam would later write: “I did not know then who Ben-Gurion was, but I knew about Count Bernadotte.”4

Three years later, Bernadotte would be accused—mostly by Stern Gang Zionists—of giving priority to Scandinavian prisoners over Jews from Nazi Concentration Camps. These charges were examined by the respected political scientist at the University of Götegorg Sune Persson, who concluded that: “The accusations against Count Bernadotte … to the effect that he refused to save Jews from the concentration camps are obvious lies.” Persson then lists numerous prominent eyewitnesses on behalf of Bernadotte, including Bernadotte’s close friend Hillel Storch, the representative of the World Jewish Congress in Stockholm, who estimated that the White Buses had saved “at least 5,000 Jews, of whom 4,000 were sick and 1,000 were children.”⁵

The Mediator

Did it not come to your mind that the “Pilgrims” who came from England to colonize this country came to realize a plan very similar to your own? Do you also know how tyrannical, intolerant and aggressive these people became after a short while. Being baptized in Jewish water is no protection either.—Albert Einstein in a letter of March 17, 1952, to Louis Rabinowitz, a Revisionist (right-wing) Zionist who had written to him in praise of the Israeli regime and its ongoing colonization in Palestine.⁶

In 1945, the end of the World War was not the end of the world’s wars. Au contraire: What might well have been called the Mother of All Wars spawned many mini—and a few not so mini —post-war wars. One of the most important of these was the 1948 war in Palestine, the war that led to the creation of the State of Israel and, at the same time, for Palestinians, to al-Nakba (The Catastrophe).

Many readers will know this, but it is worth repeating that, as a result of the 1948 war, more than three-fourths of what had been Palestine became Israel. More than 500 Palestinian villages were destroyed, while nearly 800,000 Palestinians were removed—mostly by force—from their homes and driven into exile.⁷ As one Palestinian historian put it: “The contemporary history of the Palestinians turns on a key date: 1948. That year, a country and its people disappeared from maps and dictionaries…. ’The Palestinian people does not exist,’ said the new masters.”⁸

If you follow history back from the 1948 War in Palestine, you quickly come to its World War II connection. The Holocaust, the Nazi gas chambers and the murder of six million Jews brought unprecedented international backing for a homeland for this people who had suffered so much. Before World War II, the Zionists had never rallied more than a small percentage of Jews to their ranks, but after the Nazis, the idea of a safe-haven country won sympathy and support from Jews around the world—especially since the U.S. and other western countries were not eager to welcome thousands of Jews as immigrants.

With this background, on November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted (Resolution 181) to divide—partition—Palestine in two and give 55% of the land to the Jews, who then constituted around 33 percent of the population, for the State of Israel.

The Zionist leadership accepted the partition—since it represented the first international legal recognition that there should be a State of Israel, although the Zionists clearly wanted more. A day after the partition vote, Menachem Begin, leader of the Zionist terrorist group the Irgun—and a future premier of Israel—declared ”The partition of Palestine is illegal. It will never be recognized…Jerusalem was and will forever be our capital, and Eretz Israel [i.e., the biblical land of Israel which included all of Mandatory Palestine, ed.] will be restored to the people of Israel. All of it. And forever. “⁹

The Arabs, understandably, refused to accept having their land simply taken and given away. Two days after the Partition resolution passed, the Arab High Command declared a three-day strike. Violent clashes broke out between Palestinians and Jews throughout the area. The Palestine-Israeli war had begun.

Even before their declaration of a state, the Zionists had expelled hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes, giving the Israelis control of a region well beyond the area of the proposed Jewish state. It was not until the end of the British Mandate and creation of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948 that neighboring Arab forces attacked in an effort to expel the Jewish forces from those areas intended for a Palestinian state.10

On that same date, the U.N. decided to step in. With the world watching, the Security Council decided to send in a peacemaker. On May 14, 1948, the U.N. General Assembly, in Resolution 186 (S-2) established The United Nations Mediator in Palestine. Of the purposes (tasks) the U.N. assigned to the Mediator, by far the most important was: “To promote a peaceful adjustment of the future situation in Palestine.”

And who would be that peacemaker? It took the U.N. a week of discussions—actually quite a short time by U.N. standards. The announcement came on May 21: The first U.N. Mediator in Palestine—selected by the first U.N. Secretary General, Norway’s Trygve Lie, and unanimously approved by the Security Council—was none other than Count Folke Bernadotte.

But, a keen (read skeptical) observer of international affairs might ask, why? What were Bernadotte’s qualifications to earn him the vote of every member of the Security Council?

To be fair, Bernadotte had at least three key qualifications: He was Swedish, and Sweden was a longtime (even during World War II) neutral nation; his reputation as a humanitarian and saver-of-innocent-lives was impeccable after the success of his White Buses Mission; and, perhaps most important, he was a friend and colleague of Trygve Lie. Remember that before he was U.N. Secretary General, Lie had helped Bernadotte negotiate and organize the White Buses.

But, here is our skeptic again: What about the Middle East? What does he know, if anything, about Palestine?

It seems quite likely that Secretary General Trygve Lie had a similar thought. So, while he nominated Bernadotte and must have seen the advantage of an internationally popular figure in that position, on the evening of May 20—the day before Bernadotte’s appointment was announced—Lie made an urgent phone call to a prominent African-American scholar and diplomat by the name of Ralph Bunche asking him to go to Paris “within a couple of days” to meet Bernadotte and then to go with him to Palestine “for a short period.”

Bunche had been working for more than a year within the U.N. Secretariat on Mideast issues, and was one of Lie’s most knowledgeable and trusted advisers. To get some insight into where Bunche was “coming from,” it’s worth noting that on the evening of Trygve Lie’s phone call, Bunche and his wife had been at a book party for Henry Lee Moon’s The Balance of Power: The Negro Vote. The party was at the Park Avenue home of Marshall Field, then publisher of PM, a liberal, afternoon newspaper.

When he called on May 20, Lie told Bunche that in going to Palestine, his title would be: “Chief Representative of the Secretary General in Palestine.” To Bunche, Lie’s request was “virtually impossible to refuse.”

Trygve Lie’s phone call to Ralph Bunche helps to give us a new perspective on Bernadotte’s needs. More importantly, it opens the door on Bunche’s critical role in the Bernadotte case—a role virtually unreported by historians or the mass media.

The War

Before discussing Bernadotte’s next steps, it will be helpful to consider the situation “on the ground”—the reason the U.N. decided to send a mediator in the first place: the war.

Here is an account of an Israeli attack on a Palestinian village [Sa’sa], one month before the U.N. considered sending a mediator: The New York Times (16 April, 1948) reported that a large unit of Jewish troops … entered the village [of Sa’sa] and began attaching TNT to the houses…. [Commander Moshe] Kalman’s troops took the main street of the village and systematically blew up one house after another while families were still sleeping inside. “In the end, the sky prised open,” recalled Kalman poetically, as a third of the village was blasted into the air. “We left behind 35 demolished houses and 60-80 bodies.” (Quite a few of them were children.)

This is but one of many existing accounts of such military assaults—which, as mentioned earlier, destroyed more than 500 Palestinian villages during the 1948 war. Readers can find reports of these atrocities in books and articles published over the past half century. Even earlier accounts, usually with more personal experience, have been written by Palestinian historians, such as Walid Khalidi and Hisham Sharabi. And for those who may find it useful to cite Israeli sources, the “new historians” are also accessible. At one time, most Israeli writers claimed that the Palestinians (over three-quarters of a million) left their homes voluntarily or “on orders” from some Arab high command. But since the opening of Israel’s Archives in 1978, a number of Israeli historians have found—and published—more accurate accounts.11

If you were Palestinian as the war in your country moved into the second half of 1948, prospects did not look good: First, the U.N. (in November 1947) votes to partition Palestine and gives 55% of the country to the Zionists to start their own nation. Then the U.N. stands by doing nothing as the Zionist armies attack village after village, killing, raping, destroying homes and driving people out so they (the Zionists) can take over. Then they appoint a mediator—very white, very aristocratic, very Northern European—and it seems pretty easy to guess whose side he will favor.

David Hirst, one of our most knowledgeable historians, argues that when Count Bernadotte came to Palestine, although he was “determined to show neither fear nor favor, he was in reality predisposed towards the Zionists.” This, says Hirst, was partly because he was “appalled” by the Nazi massacre of Jews—his White Buses had managed to save thousands from the concentration camps—and partly because “like most Europeans, he had an instinctive affinity with the Zionists, who were mainly Europeans themselves.”12

Indeed, nothing in Bernadotte’s writing or record shows even a glimmer of sympathy for the Palestinians. Yet people, even royal family people, sometimes change.

On June 28, within barely one month of starting his new assignment, the Count put forward—distributed through the U.N. and to both sides in the war—his first proposal as a “possible basis for discussion.” It included what Hirst describes as “specific recommendations, most of them favorable to the Arabs.” One paragraph especially infuriated the Zionists:

It is however undeniable that no settlement can be just and complete if recognition is not accorded to the rights of the Arab refugee to return to the home from which he has been dislodged by the hazards and strategy of the armed conflict between Arabs and Jews in Palestine…. It would be an offence against the principles of elemental justice if these innocent victims of the conflict were denied the right to return to their homes while Jewish immigrants flow into Palestine and indeed, at least offer the threat of permanent replacement of the Arab refugees who have been rooted in the land for centuries.

The Zionists might have agreed to compromise, or at least to mediate on a number of points, but not on permitting Palestinians to return home. They could—still can—imagine hundreds of thousands of displaced Palestinians returning to their homes and the effect that would have on the economy, elections, and the character of the nation. Whatever they feared most, they feared it fiercely and—although the U.N. has included this principle (the right of return) in several resolutions, the Zionists are adamant: Palestinians shall not return to their land or their homes— even as all Jews are guaranteed the right to “return” to Israel.

What caused Bernadotte’s rapid shift from aristocracy to egalitarianism is not too difficult to figure out.

Ralph Bunche

I have been thinking a lot about Folke Bernadotte…. I would like to fly to Stockholm in his former plane…. for one day…. just to place flowers on his grave.—Ralph Bunche, March, 1949

Carrying out his assignment from U.N. Secretary-General Trygve Lie to meet Count Bernadotte in Paris, Ralph Bunche was at Le Bourget airport on May 25 when the Count’s plane landed. As he watched Bernadotte and his three-person staff deplane, Bunche was amazed, thinking (he later admitted) does one man really need a secretary and an assistant and a doctor?

Nevertheless, almost as soon as they met and had a chance to chat, Bunche and Bernadotte became friends—and collaborators.

Consider their friendship: “The Count is affable, speaks good English, fairly tall and slender, deep-lined face but nice looking,” Bunche noted after their first meeting, adding “He is eager to get to work…. Emphasized frankness and punctuality… Says if he advances an idea, he relishes criticism provided it is accompanied by an alternative plan.” That same evening he wrote to his wife, Ruth: “I think we will get on well, for he seems to be a man who will listen seriously to advice.” Indeed, we might well imagine that it was Bernadotte’s openness and willingness (read: need) to get advice that initially appealed to Bunche.13

Within a few weeks another letter to Ruth describes how their friendship had grown: “There has really never been anything like this. The Count has much of Myrdal’s dynamic quality [Bunche had served as the main researcher and writer for the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal at the start of “An American Dilemma”], and we keep hopping from one place to another like mad in our plane and often on just a few moments’ notice. As soon as we land anywhere we begin to confer and leave for someplace else once the conference is over. I get practically no sleep and miss many meals.”

A few weeks later, when both sides in the war had responded to Bernadotte’s cease-fire proposals, Bunche noted: “Count hugged me.”

Bunche and Bernadotte not only spent a great deal of their time together, Bunche’s notes include considerable evidence that he actually wrote the proposals Bernadotte submitted. Even after the assassination, Bunche, in a letter to Ruth from Paris, said his main task was to defend the Bernadotte report “which I wrote anyway.”

Meanwhile, as the war on the ground—and the Israeli demolition of Palestinian villages—continued, Bernadotte and Bunche intensified their mediation efforts. As has been widely reported, Bernadotte’s first proposal essentially called for “a one-state solution” with Jerusalem as an international city within the Palestinian section of the state—and, most importantly, the right of return for displaced Palestinians. When this proposal was, predictably, rejected by both sides, Bernadotte developed proposal #2, essentially a two-state solution, with Jerusalem remaining under U.N. control—and recognizing the right of return for Palestinians.

This second proposal was “on the table”—about to be discussed with both sides—when Bernadotte’s car was ambushed in Jerusalem. It was September 17, 1948.

The Assassins

The decision to assassinate Bernadotte was taken by the Fighters for the Freedom of Israel, a militant Zionist group known by its Hebrew acronym Lehi. Founded in 1940 by Avraham Stern, its aim was to terrorize the British—and Palestinians—into leaving Mandated Palestine, then to turn all of Palestine into a nationalist, Hebrew state, into which Jewish immigration worldwide would be unrestricted.

Lehi had (in 1940) split from the Irgun—a Zionist terrorist group founded in 1931. After Stern’s death in 1942, Lehi was headed by Yitzhak Shamir while the Irgun was headed by Menachem Begin, both future Israeli prime ministers. Their tactics, however, remained the same: both employed violence or the threat of violence directed primarily against civilians in order to achieve their political aims. They also reached out to Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to offer their cooperation in return for help in driving the British from Palestine. In 1940, a representative of the Stern Gang met with a German foreign ministry official and offered to help Adolph Hitler in his war against the British. At the same time the Irgun sent people to meet with representatives of Benito Mussolini.14

While the Stern Gang and Irgun were jointly responsible for numerous attacks on Palestinian and British civilians, including the notorious massacre in Deir Yassin, it was the Stern Gang that carried out the 1944 Cairo assassination of Lord Moyne, the British Minister Resident in the Middle East.

What was the reaction outside Israel to such Zionist assassinations?

When Menachim Begin was scheduled to visit the United States, a group of America’s most distinguished Jewish leaders published an open letter of protest in The New York Times on December 4, 1948. The list of signers included the scientist Albert Einstein, political theorist Hannah Arendt, the philosopher Sidney Hook, and professor of industrial engineering and operations research at Columbia University Seymour Melman. The letter reads, in part:

During the last years of sporadic anti-British violence, the IZI [Irgun] and Stern groups inaugurated a reign of terror in the Palestine Jewish community. Teachers were beaten up for speaking against them, adults were shot for not letting their children join them. By gangster methods, beatings, window-smashing and wide-spread robberies, the terrorists intimidated the population and exacted a heavy tribute. Their much-publicized immigration activities were devoted mainly to bringing in fascist compatriots…. This is the unmistakable stamp of a Fascist party for whom terrorism (against Jews, Arabs and British alike), and misrepresentation are means, and a “Leader State” is the goal.

The Stern Gang officially disbanded on May 29, 1948, but continued its terrorist operations in Jerusalem until after Bernadotte’s assassination. Many of its members joined the Israel Defense Forces 8th Brigade, which became notorious for its massacre of Palestinian civilians at Dawaymeh.

In a 1952 interview with the Egyptian journalist Muhammad Heikel, Albert Einstein said of Begin and the Stern Gang: “These people are fascists in their thoughts and deeds.”15

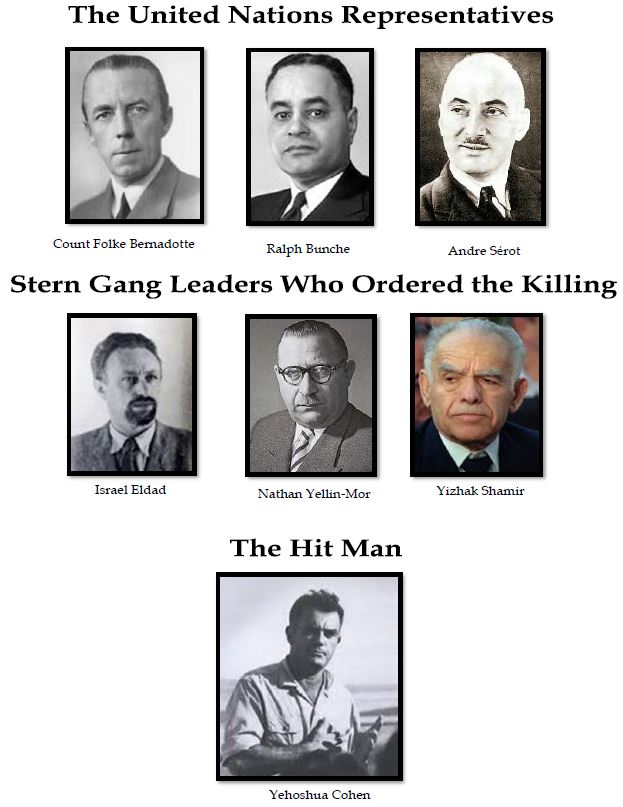

On September 10, 1948, in a Tel Aviv apartment, Stern Gang leaders took the decision to kill Bernadotte. That leadership included: Israel Eldad, born 1910 in western Ukraine and a close friend of Menachem Begin; Nathan Yellin-Mor, born 1913 in what today is Belarus and who, in 1941, traveled to Turkey on behalf of the Stern Gang to try to form an alliance with the Nazis; and, most notably, the future prime minister of Israel, Yitzhak Shamir.

Yitzhak Shamir, formally Icchak Jeziernisky, came to Palestine in 1935 from a town on the Russian-Polish border. Two years later he joined the Irgun, working by day in an accountant’s office and at night taking part in anti-British activities. When the Lehi split in 1940, Shamir joined the Stern Gang. In 1941 he was imprisoned by the British for committing acts of terrorism. A year later he escaped and, in 1943, become one of three leaders of the Stern Gang. In 1944, he plotted the assassination of Lord Moyne, the British minister of state in the Middle East, who was gunned down on Nov. 6, 1944 near his home in Cairo by two Stern Gang members, who were captured and hanged. Two years later Shamir was rearrested, only to escape again in January 1947, and become acting head of the Stern Gang, and eventually prime minister of Israel.

At the meeting in the Tel Aviv apartment, Yehoshua Zeitler was given charge of planning the assassination. Born 1917 in Palestine, he joined the Irgun in 1937. On July 6, 1938, he took part in the raid on the Palestinian village of Biyar ‘Adas, killing five civilians, the first organized attack in Mandatory Palestine by Jewish forces against an Arab village. When the Irgun decided to suspend its underground military activities against the British during World War II, Zeitler joined the Stern Gang. During the 1948 war, he commanded Lehi forces in Jerusalem that took part in the April 1948 attack on Deir Yassin, massacring over 100 Palestinian civilians. In a September 1988 interview on Israel Radio, Zeitler readily admitted his participation in the mediator’s killing. When he died in 2009, London’s Daily Telegraph noted in a May 21 obituary that he retained all his life “a long-held suspicion of Arabs and foreigners in Israel.”

At the same meeting in Tel Aviv, the Lehi triumvirate selected the four members who would form the operations team. They were Yitzhak Ben Moshe, known in the underground as a faceless, nerveless killer, “Gingi” Zinger, hardened by his time in a British prison in Africa, Meshulam Makover, the appointed driver who knew every back road in Jerusalem, and Yehoshua Cohen, the trigger-man. Cohen, born in Palestine in 1922, joined Lehi in 1938 and, by 1942, had become its most valued terrorist, teaching others how to build bombs and land mines. It was Cohen who had trained the two assassins who killed Lord Moyne in 1944. Cohen was eventually arrested by the British and sent to a detention center in Africa, but was released in July 1948 following Israel’s independence—just in time for the Bernadotte assignment.

Finally, a pivotal role in the assassination may have been played by Stanley Goldfoot. He was a recent immigrant from South Africa, where he was a staunch advocate of apartheid. Goldfoot was also an accredited journalist which gave him access to information not available to the public, such as the route the Bernadotte convoy would be following on September 17th.

The Assassination16

Count Folke Bernadotte arrived at Kalandia airstrip, just north of Jerusalem, in the new state of Israel at 10:15 a.m. on September 17, 1948. After a stop in Ramallah, he took a three-car escort to the Mandelbaum Gate, which divided the Arab and Jewish zones of Jerusalem. There he was joined by an Israeli Army liaison officer by the name of Captain Moshe Hillman, and the convoy headed for lunch at the YMCA on Jerusalem’s King David street.

Mid-afternoon, September 17: Stanley Goldfoot goes to the Government Press Office in Jerusalem where he learns that Bernadotte will be arriving in the city around 5 p.m., and will follow a route that will take him near the Stern Gang’s camp. He races back to tell the assassins. Around 4 p.m., four men dressed in Israeli military uniforms leave the camp in a jeep.

Around 5 p.m.: Following lunch, Bernadotte’s three car convoy enters the Katamon Quarter, a once affluent section of Jerusalem now under Israeli army control and largely deserted since its Christian residents were expelled at gunpoint by Zionist military forces in April. The Count sits in the back seat, on the right side, of the third car, a big Chrysler. On the left side is Swedish General Aage Lundström, head of U.N. Truce Supervision in Palestine. Seated between them is French Colonel Andre Sérot, chief U.N. Observer in Jerusalem. Sérot had asked to sit next to Bernadotte so he could thank him personally for rescuing his wife from the Dachau concentration camp in 1945.

Shortly after passing through an Israeli army checkpoint, the convoy is stopped by a jeep blocking the road. Three men dressed in Israeli army khaki shorts, wearing berets jump out of the jeep. As they approach the first car, a DeSoto, with three young Swedes and a Belgian in the passenger seats, the Israeli Army liaison officer says to them: “It’s okay boys. Let us pass. It’s the U.N. mediator.”

Ben Moshe and Zinger then proceed down one side of the parked cars, checking the occupants’ identification papers, while Cohen goes down the other side, scanning the faces of the occupants. When all three reach the last car, Cohen pushes the muzzle of his German-made Schmeisser MP40 submachine gun through the open rear window and pumps six bullets into the chest, throat and left arm of the U.N. mediator, and another 18 into the French colonel sitting on his left. At the same time, Ben Moshe and Zinger fire at the tires and radiators of all three cars. The assassins then return to their jeep and speed off, leaving dead the 54-year-old Bernadotte and the husband of the woman he had saved from Dachau.

Sérot’s killing, the assassins would later admit, was a mistake. The general thinking is that they mistook him for Lundström who, according to protocol, should have been sitting next to the mediator—and who, as a U.N. supervisor himself, would have been judged an enemy of the Zionist state.

But there’s another possibility: What if Sérot had been mistaken for Ralph Bunche?

What if the title of this article should be “Kill Bernadotte and the Negro”?17

Almost Killing Bunche

What has been left out of the “Kill Bernadotte” story is that the person the Stern Gang and most of the Zionist leadership really wanted to kill—or the person they wanted at-least-as-much-as-Bernadotte to kill—was Ralph Bunche.

By pure chance he was not in the car as he had planned to be. Two years later, he would become the first person of color to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Ignoring the echoes some readers may hear in current U.S.-Israeli policy disputes, what did the Zionists have against Bunche? For openers, we might consider three points:

1. In an online piece dated June 8, 2012 titled: ISRAELI RACISM TOWARD PEOPLE OF COLOR IS NOT NEW: AN EXAMPLE DATING AS FAR BACK 1947, Israeli historian and journalist Tom Segev wrote:

Shortly after Bunche arrived in Palestine in the summer of 1947, Moshe Shertok, the “foreign minister” of the Zionist movement (the state of Israel did not yet exist), accused him of having “a Negro complex.” Shertok wrote to Golda Meyerson (later Golda Meir, as Israel’s prime minister): “We are now dealing with Negroes who are afraid the Jewish state will harm their standing.” He went on to “explain” that Bunche and others with the “complex” are afraid that if there is a Jewish state, Americans “will start yelling at Negroes: Go to Liberia.”

Shertok did not argue for assassinating Bunche but—at the very least—a man with “a Negro complex” is not to be trusted.

2. For many years, Bunche had been a supporter and a colleague of prominent Reform Rabbi Judah Magnes, who along with people like Hannah Arendt and Einstein, advocated a “bi-national state” with equal rights and equal power for Arabs and Jews.18 Indeed, Magnes was probably the single most eloquent and persistent advocate of such a state.19 “Bunche consulted [Magnes] frequently, advocated on his behalf, and tried to bring about the establishment of a Jewish-Arab confederation.”

3. Perhaps most nettling to the 1948 Zionists and Stern Gang was Bunche’s collaboration with Bernadotte which so far had produced proposals similar to those of Magnes.

The day after the assassination of Bernadotte, Bunche wrote to his wife Ruth: “Just think. That was only the second or third time since we’ve been out here that I wasn’t riding next to him in the back seat of the car. It just wasn’t my time to go, I guess.”

Bunche had stayed behind in Rhodes to put the finishing touches on the new peace plan to be submitted to a special session of the General Assembly in Paris. Having done that, his plan was to join Bernadotte in Jerusalem, flying from Rhodes to Haifa, then on to Kalandia, then by car for lunch with his friend at the Y.

But something happened. His secretary, Doreen Daughton, a British subject, was stopped by an anti-English Israeli officer in Haifa, and Bunche stayed in Haifa until his secretary was allowed entry into Israel.

That may have saved his life. Unaware of the delay in Haifa, the assassins who shot Bernadotte and Sérot, may have thought they got the count and his consigliere.

Years later, Yehoshua Cohen, the man who shot Bernadotte and Sérot, admitted the murder of Sérot had been a mistake. “I know we killed the wrong man,” he admitted. “The black man [Ralph Bunche] was the right man. He was the man with the ideas.”20

The Present Has Such a Rough

Way of Treading It Down

The “it” of which Henry James writes in the piece quoted at the beginning of this article, is “history.”

The killing of Count Bernadotte changed the course of history. It showed that an infant state, with near impunity, could thumb its nose at the world body. It essentially killed the final version of Bernadotte’s plan that the U.N., with the U.S. concurring, adopted on December 11, 1948 as Resolution 194. This is the resolution that calls for repatriation of, or compensation to, the Palestinian refugees. Israel has rejected Resolution 194, unilaterally declaring it “obsolete.” Even the United States has abandoned support for it. In its place we now have the longest, and arguably the most grinding military occupation in modern history. (Symbolically, the killing of Bernadotte also killed the title of U.N. Mediator, which would never again be used, being replaced by Rapporteur.)

And how have we “treaded down” this tragedy?

By unlinking it from the principles of morality.

In 1991, the conspirators Israel Eldad, Meshulam Makover, and Yehshua Zeitler regaled a live TV audience on the Israeli program “This Is Your Life,” with details of how the Stern Gang mowed down the U.N.’s first mediator. We had “a weakness for the aristocracy,” quipped Eldad, to the roar of the studio audience. “You really should have seen how he would stand with his baton under his arm,” Zeitler added, giving a burlesque imitation of Bernadotte’s military posture. And when Moshe Hillman, the Israeli captain who was part of Bernadotte’s convoy said he had known of Makover’s involvement, and the show’s host asked him if he had ever told anyone, the captain replied, again to the roar of the audience, “For 40 years, no!”

Let us assume that the Ku Klux Klan lynched someone 70 years ago and this evening we watch a TV talk show and the surviving klansmen are there without their sheet-hoods, discussing how they did it, and one says, “I kept quiet about it for 40 years,” and the audience laughs and applauds.

What would this say about us? ■

Endnotes

1 Donald MacIntyre, The Independent, Sept. 18, 2008.

2 Kati Marton, A Death in Jerusalem, Pantheon Books, 1994, p. 242

³ Page 1 of The New York Times, April 12, 1949, on the decision of the international Court of Justice. See also: Letter from Sharett to Secretary General Lie, June 14, 1950 in Israel Archives, Bernadotte, File 11B; also: The Middle East Journal, Spring 1988, “A Haunting Legacy,” p. 267.

⁴ MacIntyre, op. cit.

⁵Cesarani & Levine, eds., Bystanders to the Holocaust, Frank Case Publishers, 2002, p. 244.

⁶F. Jerome, Einstein in Israel & Zionism, pp. 220-221.

⁷ Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. xiii. See also, Pappe’s article “The Window Dressers” in The Link, Jan.-Mar. 2015.

⁸ Elias Sanbar, “Out of Place, Out of Time,” in Mediterranean Historical Review, v. 16, no. 1, 2001, pp. 87-94.

⁹ Avi Shlaim, The Iron Wall, p. 25. See also Simha Flapan, The Birth of Israel, p. 32.

¹⁰ C. Rubenberg, Israel and the American National Interest, p. 44. “It should be noted, though, that with the sole exception of the Egyptian army of 10,000 men that crossed the Negev Desert (the status of which had not yet been decided), the Arab armies engaged the Israelis in the area of Palestine designed as the Arab state, not the territory of the Jewish state.”

11 See, among many others, Ilan Pappe, Benny Morris, Simha Flapan, Avi Shlaim. Another version of Israeli history that basically denies any Israeli assaults or atrocities is still taught in many Israeli schools and still found in many super-patriotic P&F (Pap and Fabrication) websites. For a fun-to-read yet quite more in-depth treatment, see Ron David’s Arabs & Israel for Beginners, pp. 119-121. For a more in-depth (but also fun to read) treatment, see Simha Flapan’s The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities.

12 David Hirst, The Gun and the Olive Branch, 1984, p. 272

13 Brian Urquhart, Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey, chapter 12, “With the Mediator in Palestine.”

14 S. Sofer, Zionism and the Foundations of Israeli Diplomacy, 2007, pp. 253-254.

15 F. Jerome, op. cit., p. 206.

16 Louis Farshee, “Folke Bernadotte and the First Middle East Roadmap,” online at Information Clearing House.

17 On the use of Negro to refer to Bunche, see Marton, op. cit., p. 226.: “’We picked up a Negro,’ Hillman, standing outside the Y, heard on his two-way radio from Israeli Army Headquarters, Jerusalem. The ‘Negro’ turned out to be Dr. Ralph Bunche … “

18 For Bunche’s collaboration/friendship/collegiality with Magnes see: Israel at Sixty: Rethinking the Birth of the Jewish State, edited by Efraim Karsh and Rory Miller, Routledge, New York, 2009, pp. 200-203 (esp. 201.)

19 ”Palestine Group Approves Magnes; Advocate of Bi-National State Evokes Tribute for Fair Play and Moderation,” The New York Times, March 15, 1946.

20 Kati Marton, op. cit., p. 254.