By Tom Hayes

Just back from a production trip, rattled as I always am on returning from Palestine to “Disney” country, I find the surreal at every turn. Strolling toward my office at Ohio University I bump into a professor of African American studies. As with each return from Palestine I am possessed with a desperate sense of obligation; I MUST communicate the horror of what I’ve just seen to everyone I speak to. I launch into a description of The Wall, the checkpoints, the humiliations, the killings. My colleague says, “Oh, it’s like Detroit.” I stand there working my jaw like a boated fish.

There is certainly a continuum of oppression that stretches from Detroit to Jerusalem. The hand of the U.S. government is visible every step of the way. It may be comforting to imagine that there is nothing unfamiliar in the world, that one’s experience provides similes for all other human realities. I don’t believe that most Americans, even those who have lived the darker side of American culture, have a real correlative in experience for comprehending the dimensions of what is happening in Palestine.

Race-based mass incarceration? Yes, Detroiters know that. And they know the not infrequent impunity for race-based murder by officials of the state. Having experienced both environs, I detect a qualitative difference.

My just-back “reentry” mental state drives me to take a stab at it. “Detroit will be like Palestine when an F-16 blows an apartment building full of sleeping families to smithereens because a suspected criminal might be in the building.” My colleague doesn’t buy that as an accurate simile of the situation and bustles off to her office. That sort of unhinged racist violence is not plausible to her, or to most Americans without direct experience of the Zionist project.

That idea encapsulates what has fueled my work for the last 34 years—a drive to present a grounded “reality of the world” in which Palestinians are included as humans. On its face that doesn’t seem like a particularly ambitious goal.

Until you realize that what passes for information about Israel here in the States is a linguistic burka forced on information so that its real face cannot be seen. It matters not how articulate, reasonable, how logical and incisive the Palestinian voice may be, it is framed as “biased.” The voices of Israel’s supporters are not framed as biased. They are “objective.” The New York Times Israel/Palestine bureau chiefs have, for decades, been Jewish. Some of these “objective journalists” have had family members actively serving in the very Israeli army that these journalists are tasked with reporting about. The framing that only Jewish voices are objective when it comes to the Israel/Palestine conflict is absurdly racist. Recognizing, subverting and exploiting that framing is the engine behind my new film, Two Blue Lines.

An Accidental Film

It’s January 2015. I’m stepping off the stage after the premier of the film at Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts. The “Q&A” session after the film had gone well. No serious fireworks. I roared a little when someone in the audience said “Palestine doesn’t exist anymore,” but no serious injuries.

As I come down the steps a half dozen young people circle me with cell cameras rolling. A woman identifies her group as being in the Israel Defense Forces. This of course tempts me to start yelling for security. She blurts, “Your film is anti-Israel!” Chuckling, I reply, “Nearly everyone who speaks in the film is Israeli.” “Yes,” she hisses, “but they are RADICALS!”

Since 1981 I have worked to document the human and political rights situation of the Palestinian people. More accurately, the profound absence of anything resembling human or political rights within the Palestinian community’s recent experience.

Now it’s no mystery that Israeli forces and minions of that state are not particularly keen on documentation of what is euphemistically called “the situation.” They are sensitive to cameras in situations that might take the blush off the rosy picture of “A land without people for a people without land,” or “The Only Democracy In The Middle East,” or “The Eternal Victim.” An unblemished picture of the inhuman brutality of the occupation might impact the $8 million per day in U.S. military aid that Israel receives. So the Israeli army has historically made a muscular effort to stop that sort of documentation.

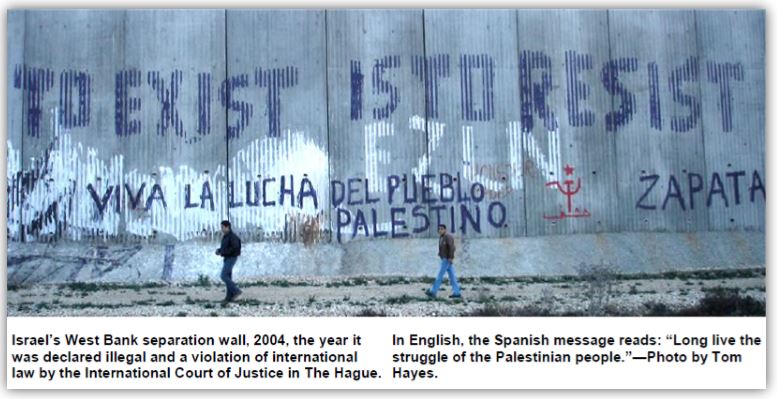

I think back to that bitter cold December afternoon in 2004. We’re headed for Jenin to follow up with Abu Imad, the father of a martyr of the Palestinian resistance. Rolling heavy with film equipment in the West Bank without a press card is like walking naked in Times Square. There will certainly be unpleasant interactions.

Mark Brewer, then Content Director at WOUB-TV, the PBS affiliate linked to my University, had contacted the Israeli Embassy prior to the trip to secure journalist credentials. He was assured that all that was needed was a letter from the station indicating that my crew and I were developing a program for the station. Mark went the extra mile of faxing the government press office prior to our departure, notifying them of our imminent arrival.

Once in Jerusalem, letters in hand, we trot off to Beit Agron, the military press office to get our cards. No dice. “You should have notified us that you were coming.” “We did.” “We don’t have any record of it.” This went on for a couple of days. Despite repeated calls between WOUB-TV and the press office, a meeting at the U.S. Consulate, and hours sitting around in Beit Agron, the press office finally said that we had been denied press cards because “The station isn’t big enough to get press cards … er … documentary crews don’t get press cards.”

Denial of the credential may have been due to my having broken one of the military censor’s rules in my film, People and The Land, and in a Link article some years back. Their cardinal rule is that you will not dispense any information about the requirements and operation of the military censor. The primary requirement of the censor is that you will not send so much as a fax out of the country without first securing clearance from, and the seal of, the military censor. All dispatches and footage have to be carried up for clearance, and the office puts their seal on the cases or documents.

We’re climbing north on highway 60, credential free, listening to what one of my crew irreverently calls “Um Kaboom” on the radio. Highway 60 is “shared” by Palestinians and settlers. There are long stretches where rolls of razor wire, stacked three high, line the sides of the road. The wire is full of birds, and no wonder. The occupation’s mass destruction of a half million olive trees since I started these trips has left the birds nowhere else to nest. How can people who claim to love this land trash it with such vigor? The birds flitting around in the rolls of razor wire strike me as a tragic living metaphor of Palestine.

An old man in a kafiyya is standing beside the road that curves through the valley below Mazra Sharkya in the northern West Bank. The ground on both sides of the road shows fresh earth and bulldozer tracks. Large roots jut through the dirt into the air. Under broken limbs I can see the ornately gnarled trunks of ancient olive trees, uprooted in the night by Israeli forces. “Romani, Romani” he repeats, pointing at the trees in a tone of confused disbelief. These trees have yielded olives and a livelihood to his village since the Roman occupation of Palestine. Thirty-seven years into the Israeli occupation they have been deemed “a threat to security.”

On the road to Jenin we’ve cleared a few checkpoints without serious incident. I’ve got my camera rolling at every checkpoint. You never know how it’s going to go. There are two Americans, our Palestinian driver, soundman, and “fixer” in the van. I’m asked for my press card. When I say we don’t have them I’m told we “can’t have that camera here without press cards.” “The press office says we can film anything” is my standard response.

American passports are pretty magical, and I always throw a “Shalom, Boker tov” and a “Mercanz” at the troops in the deepest southern drawl I can muster. The accent seems to have a calming influence on the troops, and the whole scene smacks of the Old South on steroids. As in 1940s Alabama, or 1960s Soweto.

We approach a checkpoint on a high ridge just south of Nablus. It’s a multipurpose checkpoint serving as a settlement entrance, and bus stop for settlers. The camera is sitting in my lap, pointed at the driver’s window. Surreptitious is the better part of valor. A thirty-something soldier approaches. He is toting an American M-16, sans helmet, wearing a kippa, probably a resident of the settlement. As soon as he sees the camera he says, “If you film me or any of the soldiers I will arrest you. See the beautiful hills? Film them.”

I have run into this a lot over the years. Many Israeli troops seem to have the idea that keeping cameras pointed away from the actions of the occupation will make it disappear. I also think that many of the soldiers are ashamed of what they are doing, but not this dude.

He yanks open the van door and demands “Hawiyya!” papers. The soundman hands him a Palestine Authority passport rather than the Israeli issued ID. The soldier snarls “I said Hawiyya!” Mohammed politely explains that he has given him his hawiyya. This is not received well. No document but the Israeli document will satisfy. The soldier orders Mohammed out of the van and comes over to my window. “He is playing a little game with me. Now we will play a little game with him.” He notices that I have swiveled the camera to where he is standing and says, “You are filming me. I am arresting you. Don’t move.”

Israeli soldiers cannot, in fact, arrest a non-Palestinian. They have no authority over Israeli settlers or foreign civilians. The occupation only applies to Palestinians. He struts off to a nearby shed. Mohammed is standing out in the wind, smoking beside the van. Our fixer is sitting in the back seat cursing the soldier and cursing Mohammed for pissing the guy off. We’re all pretty nervous about this “game” the soldier has in mind. The soldier and an Israeli policeman emerge from the hut. The cop does, by some twisted logic, have jurisdiction over me at a West Bank checkpoint. He walks up and says that if he hears of me filming any more soldiers I’m going to jail. He tells us to move on through the checkpoint and, pointing at Mohammed, says “we have business with him.”

I’ve got lead weights in the belly about now. The kind of “games” the IDF plays out on Palestinian bodies don’t usually peak the fun meter. I go into full Angry White American Guy mode. “This man is my employee! I’m paying him, and I’m not paying him to sit around with you!” They tell me again to move through the checkpoint. I refuse. “I’m waiting right here until you are finished with your business and bring my employee back to the van.”

They take Mohammed to the shed and about ten white-knuckle minutes later the door to the shed opens and the three emerge. Mohammed still has his teeth, which is nice. After another “No filming soldiers” lecture, we rumble off through the checkpoint.

This cat and mouse struggle to film is emblematic of the difficulties of filming the Occupation at Play. It’s been like that for years. I’ve repeatedly been served Closed Military Area Orders. Or told that an area had been put under curfew, which meant that anyone on the streets could be shot on sight, or we’d be threatened with violence without any written order, or in a couple of cases a crew member would be assaulted to persuade us to leave an area.

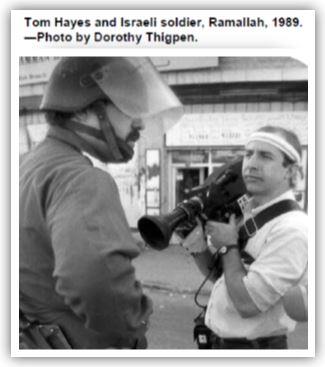

The Committee to Protect Journalists has the West Bank on its list of Worst Places to Be A Journalist. Press suppression was and is a constant feature of the working environment. In 1989 the spokesman for the military press office said in a briefing, “This is not just a war of stones. This is a war of stones and photographs.” And he meant it. There have been notable exceptions but the general rule is, when the army charges, everybody runs for their lives. I mean everybody. It doesn’t matter if you are a journalist or child. You get the score real quick. The closest I came to dying in Gaza was a day I decided to stand my ground and film people fleeing toward me, instead of bolting with everyone else. I heard two bullets fired. One looked in the viewfinder to be aimed at my chest; instead it hit a kid who was running past me, leaving a rooster tail of blood in the street beside me from his exit wound.

The People of Plan B

The roots of Two Blue Lines grew out of those obstacles. I’d have a crew of between three and seven people “on the clock.” When the army stopped us from filming, gutting the day’s plan A, I couldn’t afford to go back to the hotel and do nothing. So we’d either go up the hills in the West Bank to try to film with settlers, or go back across The Green Line into “Israel proper” in search of interesting Israelis to film. It became the standard Plan B. I didn’t think much of it at first. It was a way to keep me from going nuts in frustration, and it kept the crew busy filming something, as opposed to precipitating mayhem in the hotel bar.

A friend in Beit Sahour told me about Women In Black, a group of Israeli women who gathered every Friday just before the beginning of the Sabbath. They stand on a low wall in a square in West Jerusalem holding signs that say Stop The Occupation in English, Arabic, and Hebrew. They seemed like an interesting bunch.

Women in Black showed a lot of creativity for mildly subversive actions. Prior to “Oslo” displaying the Palestinian flag, or even any object that contained the four colors of the Palestinian flag—red, green, black and white—was illegal in Israel.

I know that sounds crazy, but that specific combination of colors was illegal. Clothing that contained the four colors was removed from store racks. In 1989 the Jerusalem Post reported that a brand of Italian pasta was removed from grocery store shelves because the packaging contained “the colors of the terrorist flag.” It’s a clue to the pathological denial within that society.

So what did Women in Black do? They had cards with the words Red Green Black White printed on them, not the actual colors, God forbid, just the words. They passed them out at their demonstrations. Their Stop the Occupation signs were black with white lettering. An Israeli plumber started showing up every week with an armload of roses and passed them out to the women. They’d hold a red rose with a green stem against their black and white signs. It may not sound like heavy activist lifting, but they were breaking the goofy law, or at least pressing its absurdity.

I met Anat Hoffman there, a Jerusalem city council person and one of the founders of Israeli Women In Black. She opened the door to a great many other interesting Israelis, who, in turn, opened more doors.

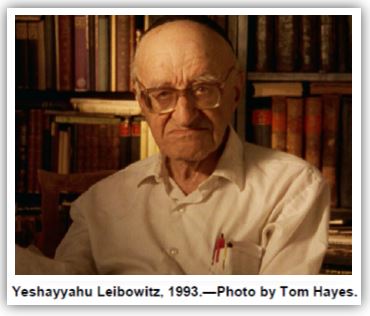

Anat put me in touch with Professor Yeshayahu Leibowitch, the man who coined the term Judeo-Nazi in 1968. A street in Israel was named for the professor after his death. He was an unrepentant Zionist “two-stater,” but he didn’t have any illusions about the character of the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

When the army was blocking us from pursuing what I considered the Real Work of documenting the lives of Palestinians, we’d trot off to film with these interesting Israelis.

In the eighties, try as I might, I could not find a non-Zionist Jewish Israeli. I met lots of people who were out protesting against the occupation, but they still bought into the whole Privileged People, this is our land, forget about the refugees riff. Many wanted to Stop the Occupation because they saw the writing on the wall; the inevitability that, if the occupation didn’t stop, Jews would become a minority population under Israeli rule.

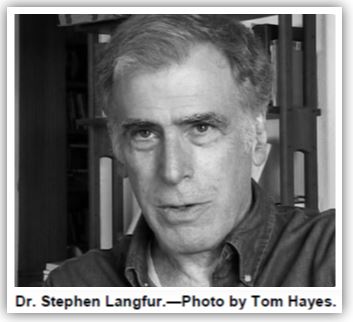

I can’t say that seemed like a particularly altruistic position. Some, like Dr. Stephen Langfur teetered on the edge of breaking through to the moral/ethical Promised Land of recognizing the human equality of Palestinians.

I met Stephen shortly after he was released from an Israeli army jail. Some backstory on him; Stephen was raised on Long Island, and was the first Jewish American to be granted conscientious objector status during the Vietnam war.

That took some doing. If you were raised Quaker, or Mennonite you had a pretty easy go for C.O. status since nonviolence is central to those creeds. But Jewish? Not so much. Stephen had to go so far as meeting with an Assistant Attorney General of the United States to get his C.O. status. Not long after he got his C.O. he bolted from the U.S. and moved to Israel. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in World Religion and Culture.

When his turn to do reserve duty in the IDF rolled around he was one of the first to refuse to serve in the occupied territories. There is no conscientious objector status in Israel. You either serve or you go to jail. Stephen chose jail. He wrote an excellent book on his experience titled Confession from a Jericho Jail, available on Amazon. His exploration in that text of what he calls “the spiral of evil” is particularly incisive.

When I first met him he was a Zionist, and that is reflected in his book. He believed in the right of Jews to create a nation state in, or more accurately on, Palestine. I’ve filmed with him periodically for over twenty years. I’ve watched Stephen transcend Zionist ideology, and take his licks for doing it. In the end he came to a place where the question of a Jewish nation state, or more precisely, Jewish self-determination was still open in his mind. However he came to reject the exercise of that self-determination on Palestinian lands. He acts as a sort of guide through Two Blue Lines, aging decades before the camera.

The 2004 production trip was soul crushing. The deterioration in the lives of my Palestinian friends was breathtaking. Makeshift checkpoints had transformed into eerie industrial human processing plants. The settlements had exploded, vandalizing and transforming the landscape. And THE WALL. Filming from a roof in Aida refugee camp, the schematic quality of the land grab hits you in the face. The wall butts up a couple of feet from the houses in Bethlehem and all the land, the olive groves and fields, have been cut off of the community.

I made some new contacts in Israel on the 2004 trip including actual post-Zionist Israelis. One of them was a professor at Hebrew University named Victoria Buch. One day at Hawarra checkpoint, as she watched the base harassment of every Palestinian who wanted to either enter or leave Nablus, she turned to me and said, “All the Zionism has gone out of me.” I loved her for that. She died a couple of years ago and I grieve her passing.

Victoria put me in touch with Hana Barag, once secretary to Prime Minister David Ben Gurion, and later on the staff of General Moshe Dayan. Hana was born of German parents in Palestine before there was an Israel. In her retirement she joined Machsom (blockade) Watch, a group of Israeli women who monitor, intercede in the name of humanity when possible, and report on Israeli army behavior at the hundreds of checkpoints and obstacles in the West Bank. A warm hearted, pocket-sized Jewish grandmother, she bustles around the checkpoints, talking to people waiting in line, and phoning army officials to try to solve the crisis of the moment in some Palestinian’s life. Army officials know who she is, and they take her calls. Hana serves as another sort of guide through Two Blue Lines.

Spend some time at the hundreds of checkpoints and what you see is a mechanism that sucks little pieces of life out of every Palestinian, every single day. It is vampiric. Drop by drop their lives disappear into the waiting. Waiting for a permit. Waiting in a line to show the permit you waited for so that you can do something that actual humans do, like go shopping, or see the doctor, or visit family. Jessica Montel, ex-executive director of the Israeli Human Rights organization B’TSelem, has called this constant taking-of-life as a clear case of “collective punishment,” and a violation of international humanitarian law.

Grinding through the footage after the 2004 trip I started seeing something unexpected climbing out of the screens onto the editing console. At that point it was something that I rejected categorically.

Why Plan B

In 1981, when the fire lit under me, I was reading anything I could lay my hands to about Palestine, Palestinians, political Zionism, the creation of Israel. One text of particular clarity was (and still is) The Question of Palestine by Edward Said. I called Professor Said at Columbia and explained that I didn’t think Americans had any idea what was happening to Palestinians. I wanted to do a film that would change that, and had found his book particularly illuminating. Would he come on board as a consultant for the project? Edward was polite in the face of my naiveté.

This isn’t an exact quote, but it’s close, “Tom, it’s nice that you care, but we Palestinians need to take control of our own narrative.” He indicated that he was just too busy with that enterprise to help. Edward eventually relented and assisted me with writing the voice-over for Native Sons: Palestinians in Exile.

I never forgot that first interaction with Professor Said. His seminal statement about who needs to be holding the reigns on the Palestinian narrative rang in me. I worked very hard in both Native Sons and People and The Land to create work that would at least serve as conduits for Palestinian voices, that they might reach American ears.

Yet, staring into the screens in my editing suite in 2005, the film that was peering back at me flew in the face of Professor Said’s injunction. I noticed that some of the Israelis I filmed on “Plan B days” were actually telling the truth—the honest, empathic, truth of the enslavement of Palestinian people and the attack on their culture at the hands of the Zionist project. Not old school retail enslavement where the owner is responsible for food and shelter of those whose lives he “owns.” I’m talking wholesale, big lots of enslavement; just chain their lives, let them starve, and hope they find a way to run away.

In 2007, I cobbled together enough grants to mount another production trip to Palestine. I wanted to be there for the fortieth anniversary of the 1967 war.

I got a great wake-up call from one of my enablers in Gaza on that trip. I was prohibited by Israeli forces from entering Gaza, but Palestinian friends were there filming for me. My friend, Mohammed, said something that forever changed how I see “the situation.” We were discussing filming dates and I was adamant that cameras be rolling through what I was calling “the anniversary of the occupation,” June 5, 1967. He was perplexed. “June 5th, not May 14th? Oh, you’re talking about the anniversary of the Naksa, not the Nakba.”

Mohammed was born in a refugee camp in Gaza. For him, for his parents, for all the people of his hometown, the occupation began on the day that Israel declared its independence. It began with the Nakba, the Catastrophe that left his family locked outside their homes, their town, their land. The 1967 war was, as far as he and his community are concerned, the Naksa, the “Setback.” It wasn’t particularly significant for the vast community of Palestinian refugees. For Palestinian refugees, every inch of land controlled by Israel is occupied territory. That is their narrative, lived for sixty-seven years, and it should be recognized.

During that trip I leaned even harder on gathering the testimony of progressive Israeli Jews. Back in the States, sifting the footage, the suspicions that I had had about the film’s intent became clearer. It is that way with a documentary. There is something in a mountain of film that says “I know who I am, what I want to be. Listen to me.” If you wind up with the documentary you thought you were making when you started a project, you probably should have stayed home. You didn’t discover anything new, and stuck with the preconceptions you had when you started.

What was climbing out of the screens into my editing room was the picture of a film that swerved one hundred eighty degrees away from Edward Said’s pronouncement on control of narrative. I started seeing a film that handed the story of the Palestinian experience over to Israeli voices. That seemed too wrong to contemplate. My gut reaction was “No, no, and absolutely not!” I spent about a week prowling the night, thinking, rethinking, rejecting, weighing the approach. It was such a twisted idea, I had a hard time getting my head around it.

There are some life, death, and destruction elements that had to be considered in the equation. There had been Israeli reprisals against individuals and families who spoke candidly to my camera in People and The Land. Abu Imad was shot twice and his family home regularly ransacked by Israeli forces. One of my fixers was shot in the stomach after he ignored an Israeli order to “stop that journalism shit.” The father of one of my subjects died at a checkpoint while suffering a heart attack. The ambulance he was in was denied entry to Jerusalem. This is not hypothetical. The Zionist sword hangs over the neck of every Palestinian. It’s an honor that so many Palestinian people have provided access to their communities and given my camera their testimony. An honor that so many cared to protect me and my crew from the Israeli army.

There is responsibility, and there are consequences for the actions of documentary makers. Every time I have gone back to Palestine the lives of my Palestinian friends have been further debased by the Zionist project. It’s one of the things that has made the work of documenting an inescapable obligation. That and the knowledge that I, and my country, are responsible for that debasement.

I spoke about that grinding guilt with one of my longtime contacts the last time I was in Palestine. He put a gentle hand on my arm and said, “Tom, what makes you think they wouldn’t have shot us if we hadn’t helped you? What makes you think they wouldn’t have imprisoned and tortured us if we hadn’t helped you? You need to forget about that.” It was a very sweet thing to say, but I cannot forget about the horrible things that happened to them, nor can I clear myself of responsibility for that carnage. The blade of the occupation never wavers, patient in its hunt for the next person to defy it. As a filmmaker, you’d be crazy not to think about that, if you care at all for your fellow human beings.

On a trip after the second Intifada I contacted a health care professional who had provided excellent clinical analysis of the impact of Israeli ordnance on Palestinian bodies during the first uprising. I was curious about the escalation in degree and scope of injuries he had recently encountered. I was invited to his home outside of Jerusalem and, after tea, I broached my request to film with him again. He politely declined. “I knew you were going to ask me this. I can’t do it. It’s not worth it.” He explained that his wife had cancer and they had to go to Jerusalem for her treatments. “I could lose our permits if I appear in a film.” I didn’t press him. The tentacles of the occupation reach into every cranny of people’s lives. His was a well founded fear.

There was a time when speaking on camera about the occupation would, at worst, get a Palestinian beaten and jailed. Those were “the good old days” before the policy of targeted murder was adopted. Israel has murdered hundreds of Palestinians under that policy. Israel’s murderous brutality in the West Bank and Gaza has increased to such a point that even drawing forward footage from “the good old days” for a new film could be a death warrant for my subjects.

Just as I have footage of Stephen Langfur aging twenty years on film, so do I have footage of many Palestinians aging before the camera as their lives are squeezed in the vise of Israel’s systematic denial of their humanity. It is gripping, sometimes inspiring, and horribly tragic material.

As I prowled the night wrestling with the mode of retelling the story of Palestine, weighing the possible impact of my options, I came to a turning point.

I am no longer going to gamble the lives and families of my friends by putting them in a film that might or might not positively impact their lives. Not until they either live as free human beings, or cease to exist at all. Palestinian filmmakers know the risk/reward equation within their own community. I leave it to them and their subjects to take control of their own images and narrative.

Concurrent with the concrete implications of mode and content I was also weighing the profoundly racist nature of American media. It occurred to me that what lay before me was an opportunity. If the only voices that are presented by the media as “unbiased” vis-a-vis the I/P conflict are Jewish voices, I could build a film from Jewish voices that are actually telling the truth. Not denying, distorting, distracting, or engaging in deceit (4D Zio-ganda).

I could deploy not just Jewish voices, but Israeli Jewish voices, speaking with human empathy and passion, the truth of what the Zionist project has done to the indigenous people of Palestine.

That’s exactly what had climbed out of the screens into my editing room: an opportunity to weaponize racism against itself.

I am an utterly unapologetic proponent of human equality. I don’t believe that you have to have been a slave to know that slavery is repugnant. I have not known the experience of slavery, but I sure as hell know that practicing it is a moral abyss. Just as the strong voices of my Israeli subjects in Two Blue Lines know that the enslavement of the Palestinian people is a moral abyss.

In the end, if you truly believe in human equality, then any informed person of conscience can tell this story. I myself am not Palestinian and have been trying to find an effective means of telling this story throughout my adult life.

It goes to the title of the film. The Israeli flag contains two blue lines. Two parallel blue lines that cannot intersect anymore than the Zionist project will ever truly intersect with the Jewish ethical tradition.

There’s something else that you can do with two blue lines. You can make an equals sign. In Palestine, equality has got the deep down blues real bad.

Viewing the Future

I have been barred from entering Gaza by the Israeli military since 2004. Fortunately, by then I had developed a broad enough network of contacts to be able to work via “remote control.” I know good cameramen who will go out and gather elements that I need, be it interviews with subjects I had worked with over the years, or actualities of specific events. Bombardment, mass demolition of refugees’ houses, you name it. Nothing is out of reach.

Getting the footage shot is not a problem, but getting it out of Gaza was risky business for my comrades in the early 2000’s. It had to be smuggled out of Gaza, make its way to Jordan, and be shipped from there. It was a pretty tricky trek for videotape.

Not so anymore, and these developments lie at the heart of my optimism for the future of the Palestinian people. During last summer’s slaughter in Gaza, my comrades were able to upload footage into “the cloud” and I could fetch it without putting anyone at risk.

No physical or rhetorical wall is going to keep imagery and testimony about the facts on the ground away from the international community anymore. Any Palestinian with a cellphone camera can post what they witness to the entire planet, despite every Israeli effort to hide the truth. I believe that this new ability, afforded by new technology, to kick windows into the monstrous veil over the oppression of the Palestinians is the road to liberation. Such tyranny will not survive the clear gaze of humanity.

Unfortunately Palestinians are not much freer on the internet than in any other area of their lives. Israel has recently imprisoned three Palestinians for terms ranging from six to eighteen months for Facebook posts. Samiha Khalil, who ran against Arafat in the 1996 elections once said, “They take our lands, kill our sons, destroy our homes, but they don’t want to hear a sound.” This attitude toward Palestinian protests and resistance among Zionists is understandable. Palestinians are seen, at best, as hewers of wood and drawers of water, they are servants who should be seen and not heard.

Two million cell phone cameras, however, will not allow Israel to continue hiding its barbarity. Video is the underground railroad of the Palestinians. The cameras are weaponeyes. And there are quite a few Israelis collaborating with Palestinians in the effort to acquire and transmit those images.

B’Tselem has been supplying cameras to Palestinians in the West Bank for a decade to facilitate recording of IDF behavior. They called it the “Shooting Back” program when it first started. Apparently the idea of anybody shooting back at Israelis, even with a video camera, was unacceptable, so they changed the name to “The Camera Giveaway Project.” They have provided more than a hundred video cameras to Palestinians. I helped as I could with this enterprise in 2004, carrying a camera down to Gaza. Some of the camera equipment used to create the film 5 Broken Cameras came from B’Tselem.

When I started this work in the early 80’s the only viable format for documenting the Palestinian experience was 16mm film. This required something on the order of $30,000 worth of production equipment. On top of that, the costs of film stock, processing, and printing ran about $2,000 for an hour of raw material. Of that hour a minute or two would wind up in a finished film. It took staggering piles of money to make a documentary, be it in the U.S. or internationally.

I am no “one-percenter.” I was working freelance in TV and film, turning tricks for corporate cannibals. It paid the bills but did not leave me with the tens of thousands of dollars required to go film the human and political realities of Palestinian life. So I wrote grant applications. Bales of grant applications. I had an early Macintosh computer and I took it everywhere. On vacation, on visits to my parents, everywhere. I couldn’t afford to miss a single grant deadline. In 1990 I wrote something on the order of sixty-six grant applications that were rejected.

Grant writing was turning into a black hole. It absorbed my life but no funding could escape from it. It wasn’t like I was trying to get funding to do some irrelevant puff piece. I was trying to get the resources to document serial war crimes that were being funded with U.S. taxpayer dollars. It wasn’t until my 67th grant application that I received enough funding to finish People and The Land.

Securing the funds, however, is only half the problem; getting the film in front of American eyes was another struggle. My film about Cambodian refugees was aired nationally in primetime on PBS three times. My film on Palestinian refugees was only aired on 19 of the 200-plus PBS affiliate stations. That film is titled Native Sons: Palestinians in Exile. Martin Sheen, a totally stand-up human, served as narrator on that piece. It did get picked up by Bravo in the U.S., which was a premium cable channel at the time. The upshot was that very few Americans had the opportunity to see it. I’ve posted a fairly well restored version as a free download at https://vimeo.com/106961084. The awful thing about Native Sons is that the torturous reality it documents hasn’t changed a wit.

When I made a film about Cambodian refugees no one threatened to kill me, or my family. No one cut the phone lines to my house, or smashed out the windows of our home. No large national organizations tried to get my funding pulled to prevent the film from being completed. At the premier of that film the theater did not have to be cleared by the bomb squad, and people did not have to be searched to get a seat. All of those things happened when I made a film about Palestinian refugees.

After finishing Native Sons I might have just walked away thinking that I had given my pound of flesh, and found other topics for films. But that incredible harassment, combined with the murder of Alex Odeh for his pro-Palestinian work eleven days before the premier, convinced me that this is just as much an American issue as it is a Palestinian issue. The stupidity of the abuse I took for recognizing the humanity of Palestinian people is emblematic of the Zionist project. It didn’t intimidate me. It motivated me, another miscalculation of social gravity.

I took Native Sons out on the road and screened it on campuses across the United States in the late 80’s. The experience of publicly screening Native Sons was markedly different from screening my new film, Two Blue Lines.

There was no internet in the 80’s. No smart phones with browsers. That meant that during the Q&A after screenings, some Zionist in a suit would stand up and holler something like, “It’s all lies! You’re a lying Nazi anti-Semite!” This tactic was pretty effective. It would distract the discussion away from the issues, into personal attacks with the suit’s word against mine. If someone in the audience wanted to fact check, they’d have to track down a book at the library, or find issues of The Link.

That’s not the case anymore. I can direct the audience to a url where they can decide for themselves who the liar in the room is. It goes back to the technology question. Acquisition of media has become simplified, and radically less expensive. Access to information is massively enhanced, and the ability of Palestinians to represent their own situation has become a reality. In the face of these technological developments the status quo will not stand.

Over the years at screenings of my work, Zionists would get up and make astonishing misrepresentations of fact. Sometimes it was really silly stuff. One of my favorites was a student at Oberlin College getting up after a screening of Native Sons and hollering that, “Your film makes peace impossible.” No kidding, a film about refugees “makes peace impossible.”

More serious pimps of oppression say things like, “It’s not an occupation,” or “The Palestinians were ordered by Arab governments to leave their homes.” I always have to wonder about such people. Are they really so ignorant or misinformed that they believe the crap they spew? In the internet age it takes an act of will to be that ignorant.

In my mind’s eye I see the American public, each of us individually, chained and harnessed by our own government to the Zionist war wagon. Enslaved by the crack of a legal whip to drag it onward, paying for Israeli war crimes. If you refuse to pay you can quickly become Ameri-Palestinianized—the government can seize your home and drown you in legal bills.

U.S. government aid to Israel represents grave and extended breaches of our government’s own Foreign Assistance Act, and the Arms Export Control Act. Look them up and read them for yourself. Every April 15th every American taxpayer is obliged, under threat of asset seizure, to support the terrorist organization known as the Israeli government. We are individually and collectively complicit in genocide. Not 180 years ago. Right now, as I write.

I’ve traveled widely and I am witness to the fact that there are many places on Earth that need our foreign aid more critically and categorically than Israel.

April 15, 1991. I’m filming a group of people blocking the entrances to the IRS building. Carved in stone above their heads are these words: Taxes Are What We Pay For A Civilized Society. They are chanting, “No longer in our name! No longer with our taxes!” One by one they are picked up and carried to waiting paddy wagons. I was completely choked up at their heroism.

In the last thirty-four years that event was the only tax-day civil disobedience protest against aid to Israel at the IRS headquarters in D.C. I am aware of. I don’t understand why there isn’t one every single year. I am astonished there wasn’t one this year on the heels of last summer’s slaughter.

Years back a representative of Church World Services told me that Refugee Road, my film about the resettlement of Cambodian refugees, spurred many American churches to step up and participate in what was primarily a volunteer resettlement effort. That volunteerism saved thousands of lives, and the contribution of that film in spurring their volunteerism was profoundly gratifying for me. It left me with the clear conviction that, when Americans know about a problem in the world, they step up and address it. That conviction continues to drive me to document the situation of the Palestinian people and America’s role in their oppression.

Israel’s minions in media perpetuate the myth of a monolithic Israel, a myth critical to the conflation of the Zionist project with Jewishness. The strategy I’ve taken in highlighting the voices of Israelis who are utterly opposed to their government’s actions deflates that myth. Two Blue Lines makes one thing very clear. It is a conflict with three sides; Palestinian, Zionist, and Jewish. And it’s a conflict with no sides. Equality doesn’t have sides.

I’m betting that most people who have engaged the situation of Palestinian people have noticed a sort of zio-phrenia, a political multiple personality syndrome, when the topic comes up. People who are passionate and progressive about every other humanist agenda item you can name—civil rights, gay rights, indigenous people’s rights, environmental stewardship—suddenly golem-out, spewing dehumanizing racist rants at the mention of the word Palestinian. Or they clam up and avoid the subject.

Jewish people who are successful in climbing out of the ideological pit of Zionism are routinely labeled “self-hating Jews.” It is sophistry. “If you’re not a Zionist Jew, then you can’t be a self-respecting Jew.” Two Blue Lines presents the voices of many Israelis who seek resolution to the conflict precisely on the basis of their ethical tradition. They are people who are crystal clear that oppressing millions of people on the basis of their ethnicity is not compatible with “healing the world.” They may get tarred as “self-hating” for not dancing around the gunmetal calf, but they don’t seem to give a damn for that canard.

My hope is that their voices can reach American Jews who are at or near the tipping point. That place where cracks appear in the mental chrysalis of mirrors and the recognition of shared humanity can shine through.

Jewish Voice for Peace recently screened the film at their National Membership Meeting in Baltimore. The experience felt like coming home. It was a gas to be with so many people with the courage to disassemble their preconceptions and look at the world with clear eyes. I highly recommend that pro-equality activists engage JVP. It is inclusive, motivated, and growing.

I’m optimistic about the future of Palestinians and Jews. One reason is the impact of technology on the reality of the world which we are presented. Youtube isn’t going anywhere. Social media isn’t going anywhere. The fact that Ayman Mohyeldin was reinstated by NBC during the recent Gaza slaughter speaks to a sea change wrought by the new ability of international constituencies to organize and respond en mass to issues of concern. You can see the impact of “new media” on the growth of the BDS movement. “The cloud” and other aspects of the new technological terrain have sidelined the military censor’s ability to affect the flow of information. Powerful Palestinian voices like Ali Abunimah’s Electronic Intifada and Ramzy Baroud’s Palestine Chronicle are now easily accessible, as are those of non-Zionist Jewish activists like Phil Wiess’s Mondoweiss. All of this is pushing toward a tipping point in American awareness of the realities of the conflict.

I’m also optimistic because this blip on Jewish history called Zionism has no real foundation. Jewish culture and its ethical tradition have survived millennia without territory or armies. It has survived worse assaults than this political ideology and there’s no reason, from a historical perspective, to think that the international Jewish community will not eventually shake it off.

Of all the territory in all the world, Zionists could not have made a worse choice for this extravaganza. Palestine, the only permanent land bridge between Africa, Europe, and Asia, has said hello and waved goodbye to more invaders than any other cultural group on Earth. The Zionist project might have worked out in Galveston, or Uganda, but the choice of Palestine has that musty whiff of Euro-colonial arrogance. Who needs to know history when you’re white?

There’s a saying one of my Jewish friends shared with me, “When the going gets weird, Jews pack.” The broad extent of Jewish communities across the planet speaks to that idea. Palestinians, on the other hand, have demonstrated a very different cultural model. When the going gets weird Palestinians get steadfast and hunker down. And while they are waiting for the latest crop of invaders to exhaust themselves, they make a nice pot of tea.

Those that claim “there never was a Palestinian state are just torturing language. “Palestinian” is a term of convenience, easier to say than: Generationally sequential indigenous inhabitants of the area between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean sea, serially renamed by whoever happened to have invaded most recently.

There never was Sioux state for that matter, but that doesn’t mean that the Sioux don’t have a culture, or that they shouldn’t be allowed to live on their ancestral lands and be treated like any other human being.

One argument I see frequently posted on the web by ziotrolls against including Palestinians within the broad outlines of the human race goes like this, “The United States was founded on genocide of the natives and the theft of their lands, so you’re an anti-Semite for condemning Israel for doing the same thing.” The U.S. was indeed built through genocide, under the veil of Manifest Destiny, and developed through slavery. But what was acceptable to Americans a century or so ago is not acceptable now.

The larger question is this: Does the fact that something terrible happened at some point in history provide a pass for aping the same behavior in the present? One would think that particular position would be the least likely political gambit any Jewish person would ever conceive of putting forward.

I’ve been to many dozens of events and demonstrations over the years and watched other Palestinian rights activists, as the Stones put it, “take their fair share of abuse.” I’ve witnessed time and again people treading as if on egg shells to avoid offending the sensibilities of Jewish people. Enough of that. Being forced to pay for Israel’s war crimes offends my sensibilities beyond the ability of mere language to contain. I propose a change of beat, an aggressive uncompromising shift in the meter and posture in discussion of these issues.

A good starting point is hinging discussions on the issue of human equality. Pounce on the base racism defined by Israel’s “Law of Return.” A person from Brooklyn or Bucharest who has never seen the place can “return” while a person born there cannot? People living across the street from each other are governed by two sets of laws, applied on the basis a person’s ethnicity? The anachronisms of colonial privilege are Israel’s greatest area of vulnerability and should be aggressively exploited.

America’s problem is that we are forced to foot the bill for these atrocities. Money that could be putting roofs over the heads of America’s homeless is used to demolish the homes of Palestinians. Money that could be putting bread in the bellies of America’s hungry children is used to put bullets in the bellies of Palestinian children. Money that could be improving our schools and medical facilities is used to level Palestinian schools and medical facilities. ENOUGH!

If supporters of the Zionist project want to put up the cash to continue this genocide, fine, it’s a free country. It’s also legal to give money to the Ku Klux Klan. And make no mistake, U.S. aid to Israel is the moral equivalent of a foreign government paying the KKK to shoot black people and Jews in the U.S.

The canard of Jewish entitlement that forces taxpayers to support the Zionist project must be aggressively challenged. Challenged in every venue, every time these issues arise. Zionists have made their bed. It is not the American taxpayers’ responsibility to subsidize the housekeeping. Time to quit pussy-footing around and take this on, head on.

Three decades, three films, and a river of sorrow down the line, I am more optimistic than ever about the inevitability of Palestinians living as actual human beings on planet Earth. I’m no Pollyanna. My optimism has ebbed and flowed over the decades, but I see gaps in the clouds and hints of blue overhead.

If you haven’t been to Palestine, Go! Go Now! Find a way. Encourage open-minded souls you encounter to make the trip. There are inexpensive tours and immersive experiences through the Alternative Tourism Group and the Siraj Center. I expect that the church organizations that have signed on to BDS will be facilitating a lot of trips. It is an experience you will forever regret for the pain it brings you, and forever rejoice in the human relationships and concrete knowledge you gain.