Author credits: Foroogh Farhang, Manijeh Nasrabadi, Arzoo Osanloo, Catherine Zehra Sameh, and Nahid Siamdoust

From the Editor

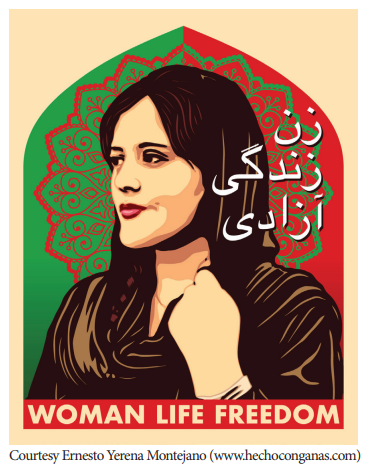

Our cover story recalls Iran in the wake of Mahsa Amini, the young Kurdish woman who was murdered in an Iranian holding cell in late 2022. She died for the offense of immodesty. The story offers historical insights about this flashpoint that pushed the people of Iran past the brink, igniting nationwide protests that quickly went global, and which continue to this day. Mahsa Amini and the cry for “Woman, Life, Freedom” won’t soon be forgotten, certainly not inside the clerical circles of Teheran.

Yet we exit 2023 with only one story on our minds: the unprecedented violence being rained down on women, children and men in the ethnic cleansing of Gaza. The numbers of dead and wounded have spiraled beyond our comprehension, with mothers across the Gaza Strip unable to protect their children while the world watches, paralyzed. The slow roll of certain death aims above all to terrorize the captive population. (See Professor Laurie King’s discussion below.)

On the other side of the pain of Gaza is the psychosis of Israel, a descent into madness broadcast live, day and night. Even against the very high bar of brutal occupation and settler colonialism, Israel’s campaign during the last three months has cycled between impunity and cruelty. International law and rules-based order have became doormats for the Israeli boot, while notions of proportionality, civility, and decency have been buried alive in the rubble. Indeed, with every updated death toll, with each hospital and school bombed, with every poet and housewife executed, it is hard to imagine what more Israel could do to clinch its status as pariah among nations.

Amid all that ongoing horror, there is also the massive self-inflicted harm to the United States. With President Biden and Secretary Blinken assuming leading roles in what is increasingly referred to as a genocide — offering more aid than ever before, more 2,000-pound bombs and white phosphorous, and even perjuring the Oval Office to promote proven hasbara falsehoods—America’s diminished standing in the world is almost certain. Washington’s ability to lecture other nations on human rights, climate change, or war and peace will be met with ever more skepticism in foreign capitals north and south.

Nevertheless, and despite the fact that Israel broke it, when the dust of Gaza does at last settle the American taxpayer will doubtless be the one who has to buy it. The dollar cost will be astronomical and the political cost at least as great. Any hope for protecting our standing in the world must pivot away from some of President Biden’s more atrophied preferences in the Middle East, including his awfully misbegotten war on Gaza.

The American President must demand that Israel Ceasefire Now.

Nicholas Griffin

Executive Director

Iran, In Her Name:

Women Rise, State Violence, and the Future of Iran

In late September 2022, the Arab Studies Institute in collaboration with George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government, Center for Global Islamic Studies, and Middle East and Islamic Studies Program broadcast the webinar, “In Her Name: Women Rise, State Violence, and the Future of Iran.” Five professors with deep knowledge of the Islamic Republic – Foroogh Farhang, Manijeh Nasrabadi, Arzoo Osanloo, Catherine Zehra Sameh, and Nahid Siamdoust – reflected on the protests that had erupted in the country earlier that month after the killing of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman from the northwestern province of Kurdistan who died in police custody in Teheran after being detained for allegedly not wearing her hijab in accordance with government standards.

More than 500 people have been killed during the protests since they began, including dozens of children. Thousands have been arrested, and though many were released after a pardon by Supreme Leader Ali Hosseini Khamenei in February 2023, some remain imprisoned. Seven prisoners who were convicted by the courts have been executed.

Though protests have dwindled over the past months they have not disappeared, with workers continuing to demonstrate and strike and an increasing number of women reportedly appearing in public without a headscarf. The regime is attempting to counter dissent through such actions as a new “hijab bill” that metes out harsher fines and punishments for women who do not wear the hijab properly and men who wear “revealing clothing that shows parts of the body lower than the chest or above the ankles.”

Yet as Human Rights Watch Senior Iran Researcher Tara Sepehri Far said recently, “Iranian authorities can’t erase the mounting frustration, louder calls for fundamental change, and the resistance and solidarity in Iranian society in the face of mounting repression.”

The 2022 webinar, whose edited transcript follows, provided crucial context about the protests, Iran’s revolutionary history, the Iranian diaspora, and current political struggles that is still of profound relevance today. Dr. Negar Razavi of Northwestern University and Dr. Bassam Haddad of George Mason University served as the webinar’s moderators.

What is different this time about the protests?

Nahid Siamdoust: We have seen an arc over the last five or so years in which hopes for reform have come to a dead end within the Islamic Republic, in part because of the engineering of elections. And this is on the heels of a pandemic and years of severe economic sanctions by the United States. These protests are coming at a time when people have been doing very badly economically, socially, and politically. Further, with the 2021 election of Ebrahim Raisi, there has been an increased presence of the morality police. We have seen videos of state violence against women on social media. This is all the culmination of years, but the recent humiliation and greater repression against women have pressurized the situation. What’s different is all these elements coming together. In addition, the 22-year-old who was killed was of Kurdish ethnicity, and this mattered because the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” has been used in the Kurdish realm for several years. The fact that this is uniting people across Iran, not just on gender issues, but on overarching issues, and connecting different provinces and ethnicities has also contributed to this moment.

Foroogh Farhang: There are a few other historical moments that matter in the way that has made this specific protest unique. One would be the Iranian Liberation Movement, not only in the last four decades, but going back to the 1905 Constitutional Revolution and taking it from there through decades of struggle that are not necessarily against Islamic rule; it’s much bigger than that. This is one of the things that very clearly connects the movement to a more international, anti-establishment, anti-patriarchal movement. And the galvanizing of the killing of Mahsa Amini connects cities with a town in the borderland of Kurdistan with Iraq and brings together not only generations of women who have been going through similar issues, but also generations of men from different ethnic minorities, self-identified religious and non-religious groups of people, and students in long-running organizations but also those founded in the last five years, as well as labor unions, such as those for teachers, bus drivers, and factory workers. These are very important connections; they allow an understanding of how the protests are unique because Mahsa is the thread connecting not only generations of women, but also other people who have been part of this struggle. So I think what is different is that it is a movement encompassing all segments of Iranian society and bringing them together.

Arzoo Osanloo: There isn’t a call for Mohammad Khatami or Mir-Hossein Mousavi to come out and represent the protestors. Some people are calling this leaderless; some people are calling it spontaneous. But what I think is important is that there’s very straightforward attention to the issues related to women and going back, as Foroogh says, to the 1905 revolution. While we have historically seen women’s issues being used as a spark to encourage their participation in wider movements, their specific concerns were sidelined. The idea was, “First, let’s get the revolution we seek. Then we’ll deal with women’s issues.” What’s happening today because of the coalescence of so many different issues around this lightning rod event is that there is stress and attention on the compulsory aspect of women’s bodily comportment and the need for autonomy, and the fact that that is center stage is important.

I go to Iran every year to do research and I was there in 1999 and in 2000 with the student protests and the closing of the newspaper, Salaam. One thing that was really striking to me this time, as opposed to that time, was something a journalist friend recounted to me after those events. In 1999, during the protests, he witnessed a young woman pulling at her hijab and yelling, “In 20 years this is all you’ve given us!” Afterward, he said to me, “But, you know, no one is willing to die for the hijab.” And now, 20 years later, this is exactly what’s happening. So we have to go back to the claim he made and ask ourselves, What has changed? And I think some of the things Nahid said about the economic strains, fragmentation, maximum pressure, and the sanctions have really come together and coalesced around this major event.

Manijeh Nasrabadi: I’ve been talking to different Iranians in the diaspora, and while there are a million different points of view and opinions I hear so many people saying, “I have dreamed of this. I have been waiting my whole life for this.” I think we need to underscore the fact that this is a far more radical movement and wave of protest than what we have seen in the past. This is a unified determination that a government that harasses and arrests and tortures and kills women for so-called improper hijab must go. People are absolutely at the place where reform does not seem viable or even desirable. The demand is for an end to the Islamic Republic form of government, an end to theocracy. It is massively significant that patriarchy, patriarchal authoritarianism, and patriarchal state violence have been at the center of this and have been the point of unity that can bring all the pressure and frustration with all the other issues to the breaking point. I also think it brings together the issue of persecution of women and persecution of ethnic and religious minorities because, of course, Mahsa Amini was Kurdish. While this is a moment when there is an outpouring of multiple grievances against this government, the fact that it has crystallized around women’s bodily autonomy and equality is so important for the reasons Arzoo and others have said, because that issue again and again was deemed secondary; it was always to be postponed and deferred. This opens tremendous possibilities for thinking about what a feminist alternative might look like in Iran and the fact that this is even on the table is incredible. Because the 2009 Green Movement, which mobilized many of us in solidarity at the time, was a struggle for Iranian feminists in Iran to make these issues legible. I remember some friends tried to go with signs and bring the issue of women’s equality into that moment, and nobody wanted to hear about it. It just was not there; it wasn’t resonating. That is a phenomenal shift.

Catherine Zehra Sameh: One thing that’s so important is the question of bodies and space, that is, the kind of bodily conscription that the state requires of everyone in every society in different ways. We have been hesitant to focus too much on the body because the body is so overdetermined and, particularly in Iran, women’s bodies. The hijab has been overdetermined in some quarters. Our body is unruly in protests, dissenting in different kinds of ways, and we can connect this to everything that’s going on, such as pensioners’ protests around inflation in which they said, “Our tables are empty.” This is all about the body and the body in need and the body under siege – and the body demanding new kinds of care and new kinds of ways of being. This feels like something that’s very global, because everywhere bodies are conscripted and compelled to do things.

Do the protestors share the same vision of what gender equality is or what they want to see for women in society? Do we see unity in what is being demanded on the streets?

FF: I think we have the tendency, not only the Western liberal media, but we all have the tendency to give one image that we think will serve the future of the uprising. I would rather read the uprising within its socioeconomic context, to see it under the banner of Woman, Life, Freedom, but also point out that it is seeking something beyond that and that it brings together socioeconomic civil aspects of our lives that have been constraints. At the same time, it is important to complicate the binary image of oppression versus freedom, which is fueled not only by Western media, but also by the regime itself. Both parties are feeding an image of oppression versus freedom, East versus West. The Islamic Republic was in fact trying to differentiate itself from Western or Eastern, capitalist or socialist parties that existed at the time. What we need to do is get to the grassroots and see the multiplicity that is happening. Some of that fits into the image that the Western liberal media is trying to present. We have, for instance, Masih Alinejad in Voice of America and in her pictures with Mike Pompeo and her support of Donald Trump. One of the images that we had not previously seen is the many women not from the center but the so-called periphery of the Iranian state, which is the borderlands. That connection is being shown in recent days and only in recent days. We must not forget about that multiplicity and we need to let the multiplicity that is meeting on the streets be voiced and not to impose a reading or interpretation on it. We need to take those conversations from that context and engage with them as what they are: conversations happening between student organizations usually considered progressive, women’s and young left-wing movements and unions, people in the streets, and women who watch Voice of America or BBC Persian. And there’s nothing wrong with any of them. These conversations are finally happening. The stigmas should be put aside and we should see what we can add to each other’s conversations. This multiplicity already existed but is now being voiced.

NS: There is now a percolation of the bare truth that women’s freedom, women’s choices to dress as they wish and to live the lives that they wish is intimately connected to the freedom of the nation as a whole. That is the truly unique aspect of these protests versus those that happened previously. Beforehand feminists, both in Iran and outside of Iran, didn’t really want to engage with this Western obsession of the hijab. For four decades they’ve been saying the hijab is secondary, let’s put it on the back burner. What’s happening now is the realization – because of images we’ve seen, because of the girls of Revolution Street and so on of the past years – that there won’t be freedom from repression unless women have their freedom. There is multiplicity. But whether we’re talking about feminists inside Iran or outside or protesters on the streets or elsewhere, I think that is the one understanding they have. Otherwise, as far as the hijab is concerned, Hassan Rouhani’s government conducted a poll in 2018, I believe, and even the government reported that 49% of Iranians are against compulsory hijab. An independent survey in 2020 showed that 72% of Iranians are against compulsory hijab. We’ve been building up to this moment and on that issue there seems to be widespread agreement.

MN: I hear a lot of people saying that it’s no longer enough for the Iranian government to say, “No more mandatory hijab.” That’s no longer going to cut it because people understand it as a kind of nexus point for the larger authoritarian structures of state violence and surveillance and control and as a quintessential or crystallizing symbol of the various oppressions. It’s a significant difference as well that people are not really willing to accept a concession around one thing. They want total systemic transformation of their society.

CZS: We’re tired of what’s been happening for many years. We’re tired of the ways in which Islam is spoken in our name. There is broad-based support for this movement even if some people aren’t out on the streets.

Women have been struggling for their rights in Iran on multiple levels and in various forms – in cultural, legal, and political ways. Can you speak about how women in Iran have been fighting for their rights through these channels?

NS: In the cultural realm, Iran has more female film directors than most Western countries. And in their productions, you see critical representations of gender relations in Iran. So people have been engaging with these questions culturally, but especially since the onset of the internet. Cultural regulations that have been applied to certain realms affecting women such as the ban on solo female singing have been taken down by social media. There’s this huge rift between what the government officially permits and the everyday life that Iranian women have been carrying out, whether as musicians or in their private spheres. Things are happening on social media, a sphere independent from state control that the majority of Iranians partake in, and this has gradually allowed for a spillover from that life into the public sphere. This has meant breaking down barriers of what is permissible, what is possible, what is already part of everyday life. Over the last few years, women have been untethering their bodies from state control in very public, spontaneous acts of dancing in the streets. These shifts are something we need to keep in mind when we talk about how this moment has been made possible. We need to factor in the alternative life on social media that Iranians have been engaging in over the last decade.

AO: I’ll start with the 1979 revolution. The visual symbol of women resisting the headscarf has been seen going back to March 1979 with women’s movements in the streets. We have to remember that people call the Iranian revolution an Islamic revolution, but before that it included considerable support and involvement from the left, whether it was the religious left or the secular left. The values that brought them together were anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist strains that aligned many with the goal of toppling a monarchy. The “woman question” was a key ideological concern of the revolutionary struggle reforming the state and shirking off the imperial yoke. As in other postcolonial societies, say, India, this would take place on women’s bodies. So women’s bodies have been integral to the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. What I argued in my first book was that two things simultaneously happened. On the one hand, women’s rights were defined as freedom from capitalist and imperialist exploitation and would forever be bound with this revolutionary struggle that established the Islamic Republic. But the second point, which emerges from the first, is that women in post-revolutionary Iran would now have expectations for those rights, those freedoms and dignity that made them the key ideological symbols of the revolutionary struggle. This was a discursive move, to be sure, but it was also a materialist move, such that women were now looking for tangible results. The idea of the chador – the black full cover garment – was a very important ideological locator of this new country. One member of the ulama, Ayatollah Taleghani, said in 1982, “We want the Iranian women to wear the chador to show the world that Iran has changed.” They took the chador up initially as an important signal of what had changed, which also speaks to why it’s so difficult now to challenge it. But it also speaks to the myriad concerns that have coalesced around this compulsion. That is, if women are forced to wear the headscarf, then where are their rights to freedom? Where is their promise of dignity? Where is their liberty? Where is their food? This is to say that it is not just about women’s rights, as others have said, but about anti-imperialist promises that sparked the revolution and the protests that included so much of Iran’s population at that time.

CZS: The ways in which women drew on the promises made to them in the revolution can be seen in the one million signatures campaign, which emerged in 2006 after several years of pushing for reforms in family law. The campaign said, “We were promised a new society, one in which Islam is about honoring women and women’s equality. Differentiated terms doesn’t work for us. We want to talk about our vision of equality.” The campaign brought out the everyday shifts in consciousness, the fact that people were struggling around gender roles in their homes, that younger people were experiencing a new vision of gender equality and justice. The campaign drew on that and said, “Things have shifted and women have a vibrant presence in society. They are political actors. They had been mobilizing before the revolution and certainly have been in the post-revolutionary period. Women are social actors, they are agents in society, and they are highly educated. It doesn’t make sense to have discriminatory laws.” It was a pragmatic, reform-oriented movement. But people have changed regarding this question. It’s not just about women’s equality, but other people in society as well.

AO: It’s important to remember that the Islamic Republic is an innovation. It’s an experiment. Many of the activists, the nationalists, the people involved in the revolution that brought about this new state formation didn’t know what they were going to end up with. And it was part of a broader compromise. But what it did give people was branches of government – a legislative branch, a judiciary, and an executive. I’m not saying those things didn’t exist before, but they acquired a sheen of accession to Islam. People were fighting through legal and constitutional mechanisms to force the state to make good on the promises of the post-revolutionary constitution. One way this was happening, starting in the late 1990s, was through judicial activism in the legislature and in the courts, and people using the courts to obtain their rights. Because of the discriminatory interpretations of some of the laws, it was clear that sharia is highly interpretable. The constitution, for instance, states that women and men are equal. Many postcolonial constitutions have this great language of equality. But women were realizing that they didn’t have equality. Women had to go to court, say, to file grievances against a husband. They realized they needed to build a case, whereas the men didn’t need a reason; this was the interpretation of the sharia back then, which was codified in Iran’s Marriage and Family Law, to get a divorce. This forced women, among them housewives, to read Iran’s civil code on marriage and family. Little by little, women gained important and tremendous legal knowledge, not to mention skill. Women I observed were deeply skilled at making legal claims and filing petitions in court. One of my venues when doing fieldwork were the iconic scripture reading groups, jalleseh ye Qur’an, which have been taking place for centuries and not just in Iran. But at the time I started attending in 1999 women were beginning to meet again, having stopped just after the 1979 revolution. They were also reinventing the groups, having women lead them and interpreting the Qur’an as they did, instead of having a cleric (read: male). I was struck by the way these women were inserting what I would call feminist and republican readings into their understanding of the Qur’an and saying, “We’re individuals and our religion specifies that we’re not supposed to have a mediated relationship with God. We can’t expect somebody else to tell us what all of this means. We have to do the work here, ourselves.” At one renewed scriptural reading group I attended the women read the Qur’an but they also invited guest speakers. In one session, they had a woman lawyer come and tell them how to file a complaint to get a divorce, and she also provided important practical details such as how much to pay for filing fees. They also had women politicians come and talk about how to form voting blocs for parliamentary elections. This period – soon after the war with Iraq to the mid 2000s – was a very exciting time in Iran because coalitions made up of women, but also of men, were coming together to push for legal reform, coming in from the ground floor. We saw women making claims before judges in courts winning decisive decisions. When I went back in 2006 or 2007, I met with one of the women family lawyers who had given women advice on filing petitions in court. I asked her what she thought about the state of women’s rights at that juncture. She responded, “Before, women didn’t know their rights. Now they know them too well.” So there has been a lot of legal reform to the point where if men don’t pay the bride price, mahrieh, that is required of them, they can go to jail. When I was in Iran in 2018, I met so many men who were angry because either they had spent time in jail or were going to jail because they didn’t pay. At that time the government was looking into how to change this law because women had become too savvy in using it for their own legal gains. The Islamic Republic, as a system, had initially made it easy for men to obtain divorces and forced women to become legal advocates for their own cases. They did it so well that there has been somewhat of a backlash to women’s legal savvy. To my knowledge, that law has not yet changed. However, some things have changed. Men now do need to go to court to get a divorce. They must state a reason, even though, according to that interpretation of sharia, they do not have to state one. There were rules about child custody that women fought. That was another issue in 1998, when the custody of young children – boys starting at age two and girls at age seven – would automatically be given to the father, generally due to economic logistics. There was a case where a child was killed by her father, an abusive drug addict. This was a spark that allowed the law to change. So there have been judicial reforms and workarounds, though obviously the laws in place still privilege patriarchal governance.

Regarding Western views, years ago I didn’t hear about the headscarf as much. Women would say, “It’s not the most important thing in my life. I’d much rather get my rights in marriage and divorce and child custody.” But now that’s changed to becoming a real concern with a right to bodily autonomy and individual rights. This new expression of bodily integrity is the basis for these protests, and it’s important to think about how men have now become involved. Once when I was going to Iran, around 2005, and anyone who’s been to Iran knows that when the plane lands the flight attendants come out and say that by law women must put on a headscarf. A gentleman sitting next to me turned to me and said, “Oh, I’m so sorry for you.” And I said, “Why are you sorry for me? I feel sorry for you.” He said, “What? What do you mean?” I said, “What does this say about you, and all Iranian men, that I’m forced to cover my head for you?” We talk about women’s awakening, but I think there’s an awakening about bodily integrity as related to men as well, because women have been aware of these challenges for centuries. The man was shocked and had to think about what I was saying to understand that he, too, was being oppressed by the logic underlying these kinds of laws. I actually said to him, “I shouldn’t be the one in the streets protesting these laws, you and other men should!”

Iranians inside Iran have been calling for international solidarity. What are the possibilities for building a transnational feminist movement in support of the uprising in Iran? What are the challenges to it?

MN: It’s significant that there is a call for international solidarity from so many Iranians who are risking their lives. To really take that seriously and put that into practice, there are a few things we need to be clear about. For those of us who are not in Iran, and especially those of us who are in places like the United States, which have been targeting Iran in so many ways for over 40 years, we must be clear that this is an uprising of Iranian people who want to get rid of their repressive government. They want to choose their future and their government for themselves. First and foremost, this is about self-determination, not a call for intervention by Western governments or states. Standing in solidarity means recognizing that what’s happening on the ground in Iran is historic and should serve as an inspiration to feminists and social justice activists everywhere who are engaged in so many different struggles against patriarchal violence, police, state violence, mass incarceration, censorship, and efforts by so many different kinds of right-wing forces to control women’s bodily autonomy, to deny women and queer and trans people full equality in their societies. Iranians in the streets want to know that people everywhere care what happens to them. They’re very isolated and they’re being arrested and shot. They’re risking their lives. In the face of that state violence our weapon is solidarity. It’s all we have. I was reminded of the slogan, “The whole world is watching,” which I think was first chanted by Americans who were protesting the Vietnam War in 1968. They were being beaten by police and they wanted to call attention to the state violence, the violent suppression of this very legitimate dissent. What would it mean to bring that slogan and sentiment to bear on Iran right now? We want the whole world to be watching how the police and the military behave. We want to apply pressure from below internationally against the Iranian regime, to call on it not to use mass force, to stop shooting and arresting people. We have to organize outside Iran to make it a reality that any mass crackdown there would ignite a popular global uproar.

CZS: It’s important to frame this as part of a global movement relating to the global uprisings of the last couple of decades. While this is its own uprising and should be seen as such, with particular characteristics and aspirations and goals, it’s part of an epochal shift in that there are many people, including in the United States, who are fed up with politics as usual and who feel that we need more substantial, deeper changes that reflect our desires. Though we see different things in different spaces, it’s important in all spaces to say that the sovereignty of the people and the sovereignty of gendered subjects who are asserting that the state security inscribed on their bodies is not okay will not be separated. In other words, the bodily dissent of women and others is part of a larger struggle. Those forms of sovereignty must come together and be indivisible. The Iranian example that is unfolding will have ramifications and should have ramifications for everyone no matter where they’re situated.

FF: New forms of solidarity are coming not only from the Iranian diaspora, but also from independent feminist groups in other places. That’s something to celebrate. They are recognizing and acknowledging the very contextual and local specificities of the Iranian women’s movement, but at the same time they are finding ways to connect it to their own movement, such as in Chile, the Philippines, Afghanistan, Turkey, Lebanon, and Iraq. A few lines from the Afghan women’s statement of solidarity with Iranians touches on how women are fighting against the same thing in different shapes and forms:

We women of Afghanistan, as well as a number of people and groups supporting gender equality, decisively signed the statement to express our belief that each and every government around the world, whether in so-called democratic or dictatorial form, have placed the deprivation and condemnation of women as their priority. And this refers to nothing but patriarchy and its ruling system in the whole world. We object to such a system and will never reduce it to a national government.

This is coming from Afghan women going through very similar things. The statement talks about the overlapping aspects of the Afghan and Iranian women’s fight, but at the same time it says that this is not about Islam per se, but Islamic autocracy or Islamic government. And it is not specifically about Iran or Afghanistan or the Middle East but goes beyond those boundaries. This is a powerful way of thinking about how solidarity can be built without forgetting the specificities, and at the same time keeping it independent and autonomous from movements that have existed a long time, especially when it comes to Iran and its last four decades.

What other ways are bodies regulated in Iran and how does this relate to what’s happening globally? How might these protests and demands be put into conversation with global crackdowns and feminist resistance on the question of bodily and political rights?

NS: The body is being regulated not just in terms of hijab, but also in terms of comportment in public space. That is why these viral dance videos that we’ve seen over the last few years are so important because within the state’s revolutionary discourse certain kinds of public comportment have not been considered appropriate. This also applies to men and to young men. That’s why every couple of years we see huge blow-ups with young people pushing back against these moral positions on what is acceptable and not acceptable in public, whether it’s engaging in public water fights or skateboarding contests. There is a real majority of very young people in Iran. And in these protests are 16- and 17-year-olds who are not really bound or beholden to the discourses that Iranians of perhaps older generations are conditioned to be responsive to through education or otherwise. Having gone through primary schooling in Iran in the 1980s, there is a feeling of indebtedness and guilt toward the martyrs in the Iran-Iraq War, for example. The ways in which Iranians are conditioned over decades to feel a certain way toward themselves and their society and their state should not be taken lightly. It’s not surprising that the kinds of boundary breaking we are seeing have been coming from a much younger generation who are less beholden to these discourses, not least because their lives have been so much more interconnected globally with young lives elsewhere. They’re spending half of their lives on social media and consuming all kinds of videos, whether on TikTok or elsewhere, and contributing to them. They have managed to surpass the space that I think older generations perhaps couldn’t so easily surpass. This is another unique aspect of these protests. From the very beginning the demands were clear. It is not a movement in which people slowly grew into opposing a dictator or expressing their desire for the fall of the regime. It was there from the very beginning.

MN: The other thing we see is that there’s really no concern about how this will be read in the West or how this might feed into Islamophobia in the West. People don’t care. They want their freedom. They want their liberation. They don’t want mandatory hijab and they don’t want a religious government. A related question is how we center Iran and Iranian women in this conversation when talking to non-Iranians in the US without being forced into Islamophobia and anti-Middle Eastern racism. This is important not because we always need to worry about how everything is seen in the US, but because we want to build international solidarity. If you want to build international solidarity or transnational feminist solidarity, you have to address these issues. And you have to be able to talk to people in the United States and explain that this is absolutely about hijab, but it’s about hijab in an Iranian context. It’s about the state forcing women to wear hijab and this making them constantly vulnerable to state violence and harassment and preventing their full equality in society. It is not about hijab everywhere, all the time, in every country and context. We must be absolutely clear, because that is the clarity on the streets in Iran and that is the demand in Iran. I have many students who wear hijab, and I recently said to them that the same way we have to defend the right of Iranian women not to be forced to wear hijab is the same as us marching here to defend your right to wear hijab. It depends on the context, but there must be clarity around opposing the state controlling women’s bodies. That can be the basis for international solidarity because that is what resonates. The outrage that women in America felt when Roe v. Wade was overturned – that idea that the state is going to tell me what I get to do? We have our version of that rage, where we want to go into the streets. And actually I think we’re not as advanced as people in Iran in terms of figuring out how to really resist our own patriarchal or authoritarian elements. We need to be clear that there are so many people on the streets of Iran who are saying that the government is doing these things in the name of Islam, and this is not my Islam. This is a fight about how people want to live. It’s not about religious versus secular. Though many people in Iran want a secular government, they’re not anti-Islam. People are horrified about what’s being done in the name of their faith and in the name of their religion. They very much want to stop the state from having a monopoly on defining Islam.

CZS: I have been struck by looking at this uprising side by side with Russian men fleeing conscription. Without abstracting it too much and taking away from the very specific nature of dissent, the connection is that no matter the form of the state, it requires a certain compulsion that is gendered and racialized and related to other elements like sexuality and class. People are dissenting with their bodies. They are moving away from those compulsions.

AO: There’s a tremendous sense of fed-up-ness. That is not exclusive to Iran or the regime, but it is an effect of the geopolitical context and flows of capital from the Global South to the Global North. We can see the same with forced migration. Essentially, we are seeing challenges to the nation-state system. We see individuals who are seeking a new articulation of the relationship between human rights and the state’s responsibility toward people. That’s something we cannot just attribute to a patriarchal government in Iran, but also to humanitarian catastrophes happening because of the global climate disaster, because of governments having to, for instance, pay back their World Bank loans. What we are seeing is an increase in humanitarian types of care. Governments are now doling out benefits or giving handouts because of the systems that have impoverished people. Iran is a great example because it’s a society in which people are experiencing humanitarian crises at the hands of international actors, such as so-called maximum pressure from the US, but also from within their own context. We see increasingly around the world these humanitarian situations that call for “care.” People, however, are saying, “We don’t want your benevolence, we want our rights.” This kind of articulation is something important for scholars to think about more completely.

NS: The question of the diaspora, as much as we want to keep the conversation to a focus on Iran, is a very important one when it comes to the Iranian context, because there are millions of Iranians of various degrees of departure from Iran. There are some who very recently left Iran, some who left Iran following the 2009 Green Movement, others who left 20 years ago, and so on. There is a staggered wave of Iranian diaspora communities abroad. And given the fairly closed media system within Iran itself, I don’t think some of these conversations would have happened so easily without the establishment of diasporic television channels, which for many Iranians are their source of news, depending on their preferences, whether it’s BBC Persian or Iran International or whatnot. The question of media is an important one when we consider the role of the diaspora. It can be quite disruptive and even damaging. We have seen this with certain people playing into the hands of the West trying to portray the movement in Iran in a certain light, oftentimes in a pathological or sad way. But what’s happening in Iran is defiant and if not directly joyous certainly very energetic, and so the common representation in Western media of the poor Iranian women who have been repressed is the opposite of the narrative and the story we need to tell. It’s the story of how Iranian women, over the course of the last 40 years or 100 years or even further back to the 1850s have resisted. Tahirih, for instance, was executed in 1852 in Qajar Persia for her beliefs and for unveiling. She said, “You can kill me as soon as you want, but you won’t be able to stop women’s emancipation.”

CZS: We really need to talk about the transnational and the global. We need to build a robust vision of solidarity that is meaningful to people everywhere. And we need to think about the fact that there is something different about the global uprisings of the past years in terms of the fact that they’re largely leaderless, which is beautiful but also a weakness. We have wrestled with that in the US with Occupy Wall Street and other uprisings, and we’re trying to figure out how to scale them up to more systemic change. Does this mean a different kind of state? No state? These are debates that people are having in their societies. And there are lots of connections across many regions of the world.

MN: Not just Iranians in the diaspora, but feminists and social justice activists in countries around the world can recognize in the uprising in Iran something that resonates deeply with their own desires for liberation. They want to uplift that struggle and make sure we’re all paying attention and learning and following and supporting what’s happening in Iran. Globally, our ability to do transnational solidarity has been weakened by intense levels of state repression. That’s true in so many parts of the world where we have weak lefts and weak feminist movements. If we can’t imagine an alternative to the international community of nation states, if we can’t imagine another force in the world we can turn to when things like this happen to apply so-called pressure on the Iranian government, then people end up back in the dead end of wishing that nation states were going to come to their aid in some benevolent way. The onus is on us and people all over the world to continue to work to build the alternative, that third force – that force of solidarity from below.

What might come next in Iran? Could it be the removal of the mandatory hijab or something else?

FF: I don’t think anybody has the right to even assume a future for this movement, especially considering that we have been talking about multiplicity. The state’s repression is intensifying. The most recent turn in the events has been a call for national strikes, which first started in Kurdistan through nationalist ethnic groups. There was a lot of resistance against this because many Kurdish communities were also pushing against making it about Kurdistan. But now more people are talking about national strikes and this is something to take seriously and consider as another step toward the solidarity being built among generations of women and other people in Iran. A lot of different factions and groups from within Iran and the Iranian diaspora are calling what’s happening a revolution intentionally as a way of showing solidarity with the national strikes. Uprisings and revolutions are about imagining different futures. This already is happening and has been for a long time in Iran. And this will not be forgotten and will lead us to different avenues.

AO: The issue is basically an alleged murder at the very ground level. Governments all around the world, when there are these kinds of uprisings, seek face saving – not a resolution or a solution, necessarily – but a way to lessen the pressure on them. There may be a murder trial. There will be some kind of accountability, albeit totally negligent, offered up, and there’s going to be some way that this is tried. They’re going to try to put this through existing legal channels to say, “Look, we’re following our own laws. We’re not a failed state, we have a working state system.”

NS: What we’re basically seeing is the state doing what it’s always done. It’s already trying to spin the narrative. We’re now seeing on state television the narrative that this is all the work of the Kurdish Democratic Party, that the Kurdish separatists are driving this movement. The aim is to bring about a rift among Iranian protesters. As far as whether it’s likely that the state will renege on the imposition of the compulsory hijab, we have no reason to believe that it will, not least because of the extreme repression and also because the state had the option of doing it in other spheres over the last ten years. For example, even though there’s no law that forbids solo female vocals, women were taken to court and charged with collaborating with foreign media and never given the right to sing. This might appear to be a small issue, but it’s about the upholding of a certain image or ideology of the Islamic Republic, which is very much tied to a certain representation of the female body.

CZS: Whatever happens, we can be assured that there are lots of people who want a different kind of present and a different kind of future, and one that is deeply informed by feminism and feminism from the Global South.

MN: Struggle transforms human beings and people find each other in the streets and they’re transformed forever by the experience of defying state power, of doing the supposedly impossible in resisting incredible militarism and violence through unity. That revolutionary experience and revolutionary consciousness will remain and will continue no matter the exact outcomes.

Sumood (صمود): The Power of Resilience

Laurie King

Anyone having a personal, familial, or professional connection to Palestine has been traumatized by the ceaseless and searing images of death and destruction in Gaza over the past two months. Although the Gaza Strip has been subjected to punishing military attacks by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) four times in the last 15 years (2008-09, 2012, 2014, and 2021), the current assault has redefined the meaning and depth of brutality, collective punishment, and inhumanity inflicted on this trapped civilian population. As of this writing, over 75 percent of Gazans are permanently displaced from their homes. More than 16,500 people, the vast majority of whom are women and children, have been killed by intensive bombardments with weaponry supplied to Israel by the U.S. government. Hospitals have become, in the words of World Health Organization (WHO) officials, “death zones,” and United Nations (UN) Secretary General Antonio Guterres described Gaza as a “graveyard for children.” Potable water, medicine, electricity, fuel, and food are in alarmingly short supply as humanitarian aid trucks are prevented from entering Gaza by Israeli authorities. WHO has recently warned that water-borne diseases and untreated infections will soon ratchet up an already high death toll. Even those who manage to survive Israel’s current campaign of ethnic cleansing will be burdened with the invisible scars of psychological trauma for years to come.

After a one-week “humanitarian pause,” Israel is striking civilian targets in the south of Gaza – the very region the IDF urged Palestinians to flee to for safety in early October. Nowhere in Gaza is safe. No one in Gaza is untouched by the horrific and unrelenting violence of the last eight weeks. An immediate ceasefire is imperative for the very survival of Palestinians in Gaza facing physical, emotional, social, and communal destruction. Their recovery from this unprecedented assault will require immense amounts of expertise, funds, and intensive and specialized psychological treatments for trauma and PTSD, particularly for affected children, thousands of whom are now orphans. A crucial component of trauma recovery is identifying and buttressing sources of resilience for traumatized children.

Palestinians in Gaza are remarkably resilient; they have not only survived, but have even thrived, through past Israeli assaults, despite a lack of water, food, medicine, and shelter. But they cannot survive without each other. Tens of thousands have been killed in just two months, leaving huge gaps in the crucial social and psychological infrastructure of dignified existence. Communal networks – kin, friends, neighbors – are the Palestinians’ support system and source of resilience, self-control, and endurance. Palestinian sources of resilience are therefore found not in administrative offices, clinics, or official social services provision, but rather, in their collective and communal steadfastness (sumoud) in the face of all the ways that Israel and the world have wounded and abandoned them.

This steadfastness is a source of dignity, protection, support, and strength, and is generated in and through close personal relationships with kin, friends, neighbors, coworkers, colleagues, and comrades. This communal resource of resistance and resilience is under threat as never before. Entire families have been wiped out in Gaza. Neighbors have been scattered to the winds as apartment blocks collapse, entombing thousands of people.

As a cultural anthropologist, I know that any theory of medicine and healing entails an unspoken theory of human nature. When Palestinians talk about their losses, suffering, and the inhumane conditions they have been forced to endure for years, they don’t say “trauma,” but rather use words like ihbaat (“frustration bordering on despair”), sadmah (“shock”), ridd (“contusion, crushing”), and perhaps most tellingly, qahr (“subjection, coercion, subdual”) to describe adverse and ongoing experiences of victimization, violence, abandonment, oppression, and denial of agency and dignity. The traumas endured by Palestinians are not generated within their homes by their family members so much as they are wounds inflicted by a capricious and unpredictable occupying military power that systematically deprives them of basic needs and rights, such as access to food, water, and medicine and freedom of movement to travel, work, and study, in an effort to make their lives as unlivable as possible.

Nearly 25 years ago, a short article published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine sent ripples of change across the fields of pediatric medicine, clinical psychology, family counseling, preventive medicine, social service provision, and policy making, leading to new understandings of trauma and toxic stress and giving rise to a variety of treatment modalities known as “Trauma Informed Care” (TIC). That 1999 article, “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study,” authored by R.F. Anda, V.J. Felitti, and D. Nordenberg, revolutionized medical perspectives on the etiology of illnesses as varied as depression, alcoholism, addiction, hypertension, cancer, and diabetes among American adults, tracing these and other ailments not to genetic or nutritional factors, but rather, to the socio-psychological environment of early childhood experiences.

The ACEs study shifted clinicians’ perspectives from the individual to the social, from the isolate to the system, and from the temporary to the continuous impact of trauma across the life span. Still, as a relatively new and emerging field of study and treatment, Trauma Studies, ACEs, and TIC have come under criticism from a variety of clinicians and scholars. One critique focuses on the initial sample of the case study for the 1999 article. Research subjects were drawn from a largely middle class, predominantly white sample of patients. Despite the privileged socioeconomic status of the sample, the study nonetheless revealed that 64 percent of respondents had experienced adverse childhood experiences that contributed to health crises in adulthood, illustrating that toxic stress in the home poses a serious threat to public health in the United States. The study did not look at socioeconomic, racial, or ethnic factors, however.

Yet perhaps the most productive and constructive critique has been that trauma studies do not look at countervailing factors contributing to resilience and recovery.

While there is no point in arguing that Palestinians in Gaza and elsewhere have not been traumatized by the events of the last two months – and indeed, a recent study found that rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality have increased in Gaza in particular over the last decade, and “[r]elative to U.S. population estimates, children in Gaza had between 2.5- and 17-times higher point prevalence of clinical mental health problems” – the sources and dynamics of Palestinians’ trauma, as well as historical, cultural, and political fonts of resilience, do not necessarily mesh well with the models and methodologies of Trauma Studies from North America.

Over twenty years ago, I became aware of the power and importance of Palestinian resilience while traveling from Jerusalem to Ramallah in the early years of the second (Al-Aqsa) Intifada. Twice in a row, my friend Maha and I were relatively lucky when passing through the Kalandia checkpoint near Jerusalem: A breeze provided occasional relief from the midday sun, and the wait to get through was only an hour and a half each time. Checkpoints constitute a key front line between the occupier and the occupied. But waiting in line with dozens of Palestinian men, women, and children sweltering under the sun, followed by the eye and the gun of an angry soldier perched on a hilltop above us, revealed that the true front lines of this conflict are internal: psychological and moral. And on that inner front line, the Palestinians were undefeated.

A phrase one hears repeatedly in conversations with Palestinians, whether citizens of Israel or those living under occupation, is “ghair insaaniyyah” – inhumane, lacking in humanity. Brutal IDF attacks following the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada, characterized by collective

punishment, prevention of medical care, (cont’d on p. 15)

(cont’d from p. 9) indiscriminate shooting and shelling, the use of human shields, an enforced siege, and many other violations of international humanitarian law, provided dramatic examples of Israeli inhumanity, but the checkpoints illustrated the banality and absurdity of Israeli inhumanity clearly, hour by hour, day by day.

Just a few minutes’ drive from some of the nicest hotels in Jerusalem, where vacationing American families were swimming, laughing, and eating pizza, Palestinians were lined up between cement barricades that narrowed to a tight passageway flanked by soldiers bristling with radios, guns, and ammunition. The soldiers shouted orders and waved people through, stopped ambulances, and constantly yelled at people to move back.

The crush of people was not chaotic or annoying, however, as Palestinians had devised an unspoken set of rules for passing through checkpoints. Pregnant women, the elderly, and anyone with small children were allowed to move forward in the line. As Maha and I got in line, a young woman appeared alongside me holding an infant that could not have been more than a week old. A rush of panic flooded my body; I wondered how the baby would fare if we had to wait in the hot sun for more than an hour. Before I could voice my concern or allow her to pass in front of me, though, the crowd wordlessly made room for the mother to pass through to the very front of the line.

Despite a long wait in line in the blazing heat of an August afternoon, no one slouched or whined at the Kalandia checkpoint that day. To the contrary: people made small jokes and greeted each other warmly. Most people in line around me stood tall, proud, and dignified, a mass of people demonstrating patience but not surrender, compliance but not defeat, and a degree of grace under pressure that one would be hard-pressed to find anywhere in Israel or America, where pushiness and impatience are all too common.

When one middle aged man behind us seemed to be pushing a woman near me, a woman to my right looked over her shoulder and said “al-ihtiraam ahamm ishi, khyee” (“Respect is the most important thing, brother”). A middle-aged man to my left looked straight ahead at a shouting soldier and said, “Those who respect us, we will respect them,” nodding toward the soldiers to indicate that they, though well-armed, were far from respectable or dignified in their behavior. They may have possessed immense military power, but they had sacrificed their humanity in the process.

One soldier looked embarrassed to be there, another seemed bored, but a third one, perched above us on an escarpment, worried me. He was very angry and agitated, and never put his gun down, but rather kept it pointed at us, his glowering eyes burning in a face that looked far too vicious to belong to such a young person.

Soon, Maha and I reached the end of the cement barricades and were about to pass through. Where the two long barricades came together in a v-formation, almost touching each other, I nearly tripped. Looking down I saw a metal bar protruding three inches from the rocky, rutted ground at the bottom of the barricade. One last dirty trick before you pass through, a final insult and annoyance for those who have had to wait hours to go to work, visit a sick relative, deliver important papers, or visit family members.

As each person passed through the checkpoint and showed the soldier his or her papers, however, they stood tall and walked proudly, as small children approached from the other side of the checkpoint to sell us bread, toys, candy, and cigarettes. Here the Palestinian secret weapon was on full display: a reaffirmation of the importance of maintaining one’s humanity, dignity, and perseverance in spite of decades of suffering, Israel’s cruel occupation, U.S. intransigence, and international neglect.

On the moral and psychological front lines, the Palestinians were steadfast and resilient that summer day in 2002, but with the loss of tens of thousands of family members, friends, and neighbors, and yet another experience of displacement exacerbated by hunger, illness, and unrelenting violence, Palestinians’ secret weapon of resistance and resilience has suffered a crushing blow. Those of us far from the devastation must do our part to help stem and reverse the traumatic effects of Israel’s criminal assault.

AMEU Announces the 2023 John F. And Sharon Mahoney Award for Service

At its annual meeting on Nov 14, 2023, AMEU’s Board President Mimi Kirk announced the 2023 recipient of the AMEU/John F. and Sharon Mahoney Award for Service: Just Vision Creative Director and acclaimed documentary filmmaker, Julia Bacha. The award, which carries a $5,000 honorarium, was accepted by the filmmaker on behalf of Just Vision.

Ms. Bacha’s career is deeply ingrained in documentary film related to the Middle East, starting with the award-winning Control Room (2004) and its in-depth look at the Al Jazeera broadcasting network. Her work with Just Vision includes such films as Budrus (2009), Naila and the Uprising (2017), and the 2021 Boycott, which dissects organized efforts in the United States to threaten Americans’ right to use boycott as a form of nonviolent free speech to oppose the Israeli occupation of Palestine.

The Mahoney Award was established by the AMEU Board in 2022 to recognize and celebrate exceptional contributions to uplifting and improving American understanding of the Middle East, its peoples, histories, and cultures. It is named in honor of AMEU Board member John F. Mahoney, who directed the organization for four decades. This year’s selection was the product of a several months-long search covering a broad field of nominees, including public servants, poets, artists, and activists from the United States and beyond. A Board-designated selection committee used various criteria to make its selection, including the ability to reach new and broader audiences, accountability and transparency, “on the ground” connections, and past accomplishment vs future potential. Ms. Bacha and Just Vision were selected from a field of 20 nominees.

This year’s selection committee was chaired by AMEU’s President Mimi Kirk and included AMEU Board members Rev. Darrel Meyers and Janet McMahon and President Emeritus Bob Norberg. Public members of the committee included the Middle East Institute’s Khaled Elgindy and Aline Bartarseh, Executive Director of Visualizing Palestine. Sculptor and designer Ryan Mahoney also served on the committee and represented the Mahoney family. The committee’s selection was acclaimed by the full AMEU Board.