By Rashid Khalidi

For a few years during the early 1990s, I lived in Jerusalem for several months at a time, doing research in the private libraries of some of the city’s oldest families, including my own. With my wife and children, I stayed in an apartment belonging to a Khalidi family waqf, or religious endowment, in the heart of the cramped, noisy Old City. From the roof of this building, there was a view of two of the greatest masterpieces of early Islamic architecture: the shining golden Dome of the Rock was just over 300 feet away on the Haram al-Sharif. Beyond it lay the smaller silver-gray cupola of the al-Aqsa Mosque, with the Mount of Olives in the background. In other directions one could see the Old City’s churches and synagogues.

Just down Bab al-Silsila Street was the main building of the Khalidi Library, which was founded in 1899 by my grandfather, Hajj Raghib al-Khalidi, with a bequest from his mother, Khadija al-Khalidi. The library houses more than 1,200 manuscripts, mainly in Arabic (some in Persian and Ottoman Turkish), the oldest dating back to the early eleventh century. Including some 2,000 nineteenth-century Arabic books and miscellaneous family papers, the collection is one of the most extensive in all of Palestine that is still in the hands of its original owners. (Private Palestinian libraries were systematically looted in the spring of 1948 by specialized teams operating in the wake of advancing Zionist forces as they occupied the Arab-inhabited cities and towns, notably Jaffa, Haifa and the Arab neighborhoods of West Jerusalem. The stolen manuscripts and books were deposited in the Hebrew University Library, now the Israel National Library, under the heading “AP” for “abandoned property,” a typically Orwellian description of a process of cultural appropriation in the wake of conquest and dispossession. See Gish Amit, “Salvage or Plunder? Israel’s ‘Collection’ of Palestinian Private Libraries in West Jerusalem,” Journal of Palestinian Studies, 40, 4 (Summer 2011) pp. 6-23.)

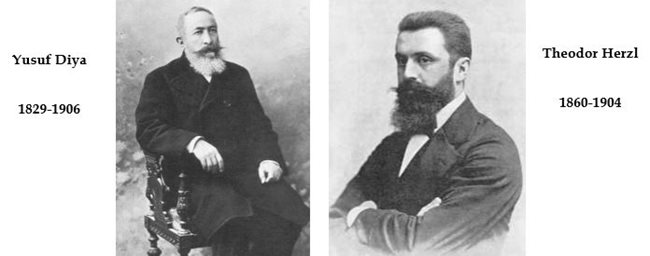

At the time of my stay, the main library structure, which dates from around the thirteenth century, was undergoing restoration, so the contents were being stored temporarily in large cardboard boxes in a Mameluke-era building connected to our apartment by a narrow stairway. I spent over a year among those boxes, going through dusty, worm-eaten books, documents, and letters belonging to generations of Khalidis, among them my great-great-great uncle, Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi. Through his papers, I discovered a worldly man with a broad education acquired in Jerusalem, Malta, Istanbul, and Vienna, a man who was deeply interested in comparative religion, especially in Judaism, and who owned a number of books in European languages on this and other subjects.

Yusuf Diya was heir to a long line of Jerusalemite Islamic scholars and legal functionaries: his father, al-Sayyid Mohammad ‘Ali al-Khalidi, had served for some 50 years as deputy qadi and chief of the Jerusalem Shari’a court secretariat. But at a young age Yusuf Diya sought a different path for himself. After absorbing the fundamentals of a traditional Islamic education, he left Palestine at the age of 18 — without his father’s approval, we are told — to spend two years at a British Church Mission Society school in Malta. From there he went to study at the Imperial Medical School in Istanbul, after which he attended the city’s Robert College, founded by American Protestant missionaries. For five years during the 1860s, Yusuf Diya attended some of the first institutions in the region that provided a Western-style education, learning English, French, German, and much else. It was an unusual trajectory for a young man from a family of Muslim religious scholars in the mid-nineteenth century.

Having obtained this broad training, Yusuf Diya filled different roles as an Ottoman government official: translator in the Foreign Ministry; consul in the Russian port of Poti; governor of districts in Kurdistan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria; and mayor of Jerusalem for nearly a decade — with stints teaching at the Royal Imperial University in Vienna. He was also elected as the deputy from Jerusalem to the short-lived Ottoman parliament established in 1876 under the empire’s new constitution, earning Sultan ‘Abd al-Hamid’s enmity because he supported parliamentary prerogatives over executive power.

In line with family tradition and his Islamic and Western education, al-Khalidi became an accomplished scholar as well. The Khalidi Library contains many books of his in French, German, and English, as well as correspondence with learned figures in Europe and the Middle East. Additionally, old newspapers in the library from Austria, France, and Britain show that Yusuf Diya regularly read the overseas press. There is evidence that he received these materials via the Austrian post office in Istanbul, which was not subject to the draconian Ottoman laws of censorship.

As a result of his wide reading, as well as his time in Vienna and other European countries, and from his encounters with Christian missionaries, Yusuf Diya was fully conscious of the pervasiveness of Western anti-Semitism. He had also gained impressive knowledge of the intellectual origins of Zionism, specifically its nature as a response to Christian Europe’s virulent anti-Semitism. He was undoubtedly familiar with “Der Judenstaat” by the Viennese journalist Theodor Herzl, published in 1896, and was aware of the first two Zionist congresses in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897 and 1898. Indeed, it seems clear that Yusuf Diya knew of Herzl from his own time in Vienna. He knew of the debates and the views of the different Zionist leaders and tendencies, including Herzl’s explicit call for a state for the Jews, with the “sovereign right” to control immigration. Moreover, as mayor of Jerusalem he had witnessed the friction with the local population prompted by the first years of proto-Zionist activity, starting with the arrival of the earliest European Jewish settlers in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

Herzl, the acknowledged leader of the growing movement he had founded, paid his sole visit to Palestine in 1898, timing it to coincide with that of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. He had already begun to give thought to some of the issues involved in the colonization of Palestine, writing in his diary in 1895:

“We must expropriate gently the private property on the estates assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our own country. The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.”

Thus Yusuf Diya would have been more aware than most of his compatriots in Palestine of the ambition of the nascent Zionist movement, as well as its strength, resources, and appeal. He knew perfectly well that there was no way to reconcile Zionism’s claims on Palestine and its explicit aim of Jewish statehood and sovereignty there with the rights and well-being of the country’s indigenous inhabitants. It is for these reasons, presumably, that on March 1, 1899, Yusuf Diya sent a prescient seven-page letter to the French chief rabbi, Zadoc Kahn, with the intention that it be passed on to the founder of modern Zionism.

The letter began with an expression of Yusuf Diya’s admiration for Herzl, whom he esteemed “as a man, as a writer of talent, and as a true Jewish patriot,” and of his respect for Judaism and for Jews, who he said were “our cousins,” referring to the Patriarch Abraham, revered as their common forefather by both Jews and Muslims. He understood the motivations for Zionism, just as he deplored the persecution to which Jews were subject in Europe. In light of this, he wrote, Zionism in principle was “natural, beautiful and just,” and “who could contest the rights of the Jews in Palestine? My God, historically it is your country!”

This sentence is sometimes cited, in isolation from the rest of the letter, to represent Yusuf Diya’s enthusiastic acceptance of the entire Zionist program in Palestine. However, the former mayor and deputy of Jerusalem went on to warn of the dangers he foresaw as a consequence of the implementation of the Zionist project for a sovereign Jewish state in Palestine. The idea would sow dissension among Christians, Muslims and Jews there. It would imperil the status and security that Jews had always enjoyed throughout the Ottoman domains. Coming to his main purpose, Yusuf Diya said soberly that whatever the merits of Zionism, the “brutal force of circumstances had to be taken into account.” The most important of them were that “Palestine is an integral part of the Ottoman Empire, and more gravely, it is inhabited by others.” Palestine already had an indigenous population that would never accept being superseded. He spoke “with full knowledge of the facts,” asserting that it was “pure folly” for Zionism to plan to take over Palestine. “Nothing could be more just and equitable” than for “the unhappy Jewish nation” to find a refuge elsewhere. But, he concluded with a heartfelt plea, “in the name of God, let Palestine be left alone.”

Herzl’s reply to Yusuf Diya came quickly, on March 19, 1899. His letter was probably the first response by a leader of the Zionist movement to a cogent Palestinian objection to its embryonic plans for Palestine. In it, Herzl established what was to become a pattern of dismissing as insignificant the interests, and sometimes the very existence, of the indigenous population of Palestine. The Zionist founder simply ignored the letter’s basic thesis that Palestine was already inhabited by a population that would not agree to be supplanted. Although he had visited the country once, like most early European Zionists, Herzl had not much knowledge of or contact with its native inhabitants. He also failed to address al-Khalidi’s well-founded concerns about the danger the Zionist program would pose to the large Jewish communities all over the Middle East.

Glossing over the fact that Zionism was ultimately meant to lead to Jewish domination of Palestine, Herzl employed a justification that was a touchstone for colonialists at all times and in all places and that would become a staple argument of the Zionist movement: Jewish immigration would benefit the indigenous people of Palestine. “It is their well-being, their individual wealth, which we will increase by bringing in our own.” Echoing the language he had used in “Der Judenstaat,” Herzl added: “In allowing immigration to a number of Jews bringing their intelligence, their financial acumen and their means of enterprise to the country, no one can doubt that the well-being of the entire country would be the happy result.” (Herzl’s letter is reprinted in “From Haven to Conquest: Readings in Zionism and the Palestine Problem,” Walid Khalidi, ed., Beirut, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1971.)

Most revealingly, the letter addresses a consideration that Yusuf Diya had not even raised. “You see another difficulty, Excellency, in the existence of the non-Jewish population in Palestine. But who would think of sending them away?” With his assurance in response to al-Khalidi ‘s unasked question, Herzl alludes to the desire recorded in his diary to “spirit” the country’s poor population across the borders. It is clear from this chilling quotation that Herzl grasped the importance of “disappearing” the native population of Palestine in order for Zionism to succeed. Moreover, the 1901 charter, which he co-drafted for a Jewish-Ottoman Land Company, includes the same principle of the removal of inhabitants of Palestine to “other provinces and territories of the Ottoman Empire.” (The text of this charter can be found in Walid Khalidi’s “The Jewish-Ottoman Land Company,” in the Journal of Palestine Studies, Winter 1993, pp. 30-47.) Although Herzl stressed in his writings that his project was based on “the highest tolerance” with full rights for all, what was meant was no more than toleration of any minorities that might remain after the rest had been moved elsewhere. (See Muhammad Ali Khalidi, “Utopian Zionism or Zionist Proselytism.”) Herzl’s almost utopian 1902 novel “Altneuland” (“Old New Land”) described a Palestine of the future which had all these attractive characteristics.

Herzl underestimated his correspondent. From al-Khalidi’s letter it is clear that he understood perfectly well that what was at issue was not the immigration of a limited “number of Jews” to Palestine, but rather the transformation of the entire land into a Jewish state. Given Herzl’s reply to him, Yusuf Diya could only have come to one or two conclusions. Either the Zionist leader meant to deceive him by concealing the true aims of the Zionist movement, or Herzl did not see Yusuf Diya and the Arabs of Palestine as worthy of being taken seriously.

Instead, with the smug self-assurance so common to nineteenth-century Europeans, Herzl offered the preposterous inducement that the colonization, and ultimately the usurpation, of their land by strangers would benefit the people of that country. Herzl’s thinking and his reply to Yusuf Diya appear to have been based on the assumption that the Arabs could ultimately be bribed or fooled into ignoring what the Zionist movement actually intended for Palestine. This condescending attitude toward the intelligence, not to speak of the rights, of the Arab population of Palestine was to be serially repeated by Zionist, British, European and American leaders in the decades that followed, down to the present day. As for the Jewish state that was ultimately created by the movement Herzl founded, as Yusuf Diya foresaw, there was to be room there for only one people, the Jewish people: others would indeed be “spirited away,” or at best tolerated.

Yusuf Diya’s letter and Herzl’s response are well known to historians, but most of them do not seem to have reflected carefully on what was perhaps the first meaningful exchange between a leading Palestinian figure and a founder of the Zionist movement. They have not reckoned fully with Herzl’s rationalizations, which laid out, quite plainly, the essentially colonial nature of the century-long conflict in Palestine. Nor have they acknowledged al-Khalidi’s arguments, which have been borne out in full since 1899.

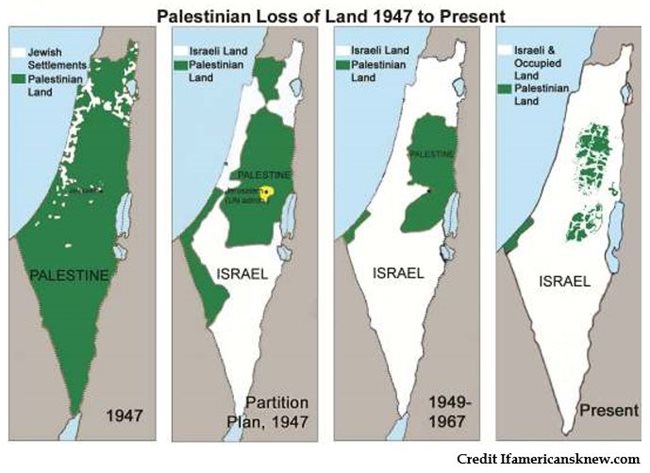

Starting after World War I, the dismantling of indigenous Palestinian society was set in motion by the large-scale immigration of European Jewish settlers supported by the newly established British Mandate authorities, who helped them build the autonomous structure of a Zionist para-state. Additionally, a separate Jewish-controlled sector of the economy was created through the exclusion of Arab labor from Jewish-owned firms under the slogan of avoda ivrit, Hebrew labor, and the injection of what were truly massive amounts of capital from abroad. By the middle of the 1930s, although Jews were still a minority of the population, this largely autonomous sector was bigger than the Arab-owned part of the economy. According to the Israeli scholar Zeev Sternhell, during the entire decade of the 1920s “the annual inflow of Jewish capital was on average 41.5% larger than the Jewish net domestic product (NDP)…its ratio to NDP did not fall below 33% in any of the pre-World War II years…” See Sternhell’s “The Founding Myths of Israel,” Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998, p.217. The consequence of this remarkable inflow of capital was a growth rate of 13.2% annually for the Jewish economy of Palestine from 1922-1947; for details see Rashid Khalidi, “The Iron Cage,” pp. 13-14.

The indigenous population was further diminished by the crushing repression of the Great 1936-39 Arab Revolt against British rule, during which 10 percent of the adult male population was killed, wounded, imprisoned, or exiled, as the British employed 100,000 troops and air power to master Palestinian resistance. Meanwhile, a massive wave of Jewish immigration as a result of persecution by the Nazi regime in Germany raised the Jewish population in Palestine from just under 18 percent of the total in 1932 to over 31 percent in 1939. This provided the demographic critical mass and military manpower that were necessary for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948. The expulsion then of over half the Arab population of the country, first by Zionist militias and then by the Israeli army, completed the military and political triumph of Zionism.

Zionism: A Colonial Settler Movement

Such radical social engineering at the expense of the indigenous population is the way of all colonial settler movements. In Palestine, it was a necessary precondition for transforming most of an overwhelming Arab country into a predominantly Jewish state. As I argue in my recent book, “The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine,” the modern history of Palestine can best be understood in these terms: as a colonial war waged against an indigenous population, by a variety of parties, to force them to relinquish their homeland to another people against their will.

Although this war shares many of the typical characteristics of other colonial campaigns, it also possesses very specific characteristics, as it was fought by and on behalf of the Zionist movement, which itself was and is a very particular colonial project. Further complicating this understanding is the fact that this colonial conflict, conducted with massive support from external powers, became over time a national confrontation between two new national entities, two peoples.

Underlying this feature, and amplifying it, was the profound resonance for Jews, and also many Christians, of their Biblical connection to the historic land of Israel. Expertly woven into modern political Zionism, this resonance has become integral to it. A nineteenth-century colonial-national movement thus adorned itself with a Biblical coat that was powerfully attractive to Bible-reading Protestants in Great Britain and the United States, blinding them to the modernity of Zionism and to its colonial nature: for how could Jews be “colonizing” the land where their religion began?

Given this blindness, the conflict at best is portrayed as a straight-forward, if tragic, national clash between two peoples with rights in the same land. At worst, it is described as the result of the fanatical, inveterate hatred of Arabs and Muslims for the Jewish people as they assert their inalienable right to their eternal, God-given homeland. In fact, there is no reason that what has happened in Palestine for over a century cannot be understood as both a colonial and a national conflict. But our concern here is its colonial nature, as this aspect has been as underappreciated as it is central, even though those qualities typical of other colonial campaigns are everywhere in evidence in the modern history of Palestine.

Characteristically, European colonizers seeking to supplant or dominate indigenous peoples, whether in the Americas, Africa, Asia or Australasia (or in Ireland), have always described them in pejorative terms. They also always claim that they will leave the native population better off as a result of their rule: the “civilizing” and “progressive” nature of their colonial projects serve to justify whatever enormities are perpetrated against the indigenous people to fulfill their objectives. One need only refer to the rhetoric of French administrators in North Africa or of British viceroys in India. Of the British Raj, Lord Curzon said: “To feel that somewhere among these millions you have left a little justice or happiness or prosperity, a sense of manliness or moral dignity, a spring of patriotism, a dawn of intellectual enlightenment, or a stirring of duty, where it did not before exist — that is enough, that is the Englishman’s justification in India.” (See “Lord Curzon in India, Being A Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy & Governor-General of India 1898-1905,” London: Macmillan, 1906, pp. 589-590.)

Those words “where it did not exist before” bear repeating. For Curzon and others of his colonial class, the natives did not know what was best for them and could not achieve these things on their own. “You cannot do without us,” Curzon said in another speech, cited on page 489 of the above mentioned book.

For over a century, the Palestinians have been depicted in precisely the same language by their colonizers as have been other indigenous peoples. The condescending rhetoric of Theodor Herzl and other Zionist leaders was no different from that of their European peers. The Jewish state, Herzl wrote, would “form a part of a wall of defense for Europe in Asia, an outpost of civilization against barbarism.” (See “Der Judenstaat,” translated and excerpted in Arthur Hertzberg, ed., “The Zionist Idea: A Historical Analysis and Reader,” New York: Atheneum, 1970, p. 222.)

This was similar to the language used in the conquest of the North American frontier, which ended in the nineteenth century with the eradication or subjugation of the continent’s entire native population. As in North America, the colonization of Palestine — similar to South Africa, Australia and Algeria and a few parts of East Africa — was meant to yield a white European settler colony. The same tone toward the Palestinians that characterizes both Curzon’s rhetoric and Herzl’s letter is replicated in much discourse on Palestine in the United States, Europe, and Israel even today.

In line with this colonial rationale, there is a vast body of literature dedicated to proving that before the advent of European Zionist colonization, Palestine was barren, empty, and backward. Historical Palestine has been the subject of innumerable disparaging tropes in Western popular culture, as well as academically worthless writing that purports to be scientific and scholarly, but which is riddled with historical errors, misrepresentations, and sometimes outright bigotry. At most, this literature asserts the country was peopled by a small population of rootless and nomadic Bedouin who had no fixed identity and no attachment to the land they were passing through, essentially as transients.

The corollary of this contention is that it was only the labor and drive of the new Jewish immigrants that turned the country into the blooming garden it supposedly is today, and that only they had an identification with and love for the land, as well as a (God-given) right to it. This attitude is summed up in the slogan “a land without a people for a people without a land,” used by Christian supporters of a Jewish Palestine, as well as by early Zionists like Israel Zangwill. In “The Return to Palestine,” New Liberal Review, December 1901, p. 615, Zangwill wrote that “Palestine is a country without a people; the Jews are a people without a country.” (For a recent example of the tendentious and never-ending reuse of this slogan, see Diana Muir, “A Land Without a People for a People Without a Land,” Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2008, pp. 55-62.)

Palestine was terra nullius to those who came to settle it, with those living there nameless and amorphous. Thus Herzl’s letter to Yusuf Diya referred to Palestinian Arabs, then roughly 95 percent of the country’s inhabitants as its “non-Jewish population.”

Essentially, the point being made is that the Palestinians did not exist, or were of no account, or did not deserve to inhabit the country they so sadly neglected. If they did not exist, then even well-founded Palestinian objections to the Zionist movement’s plans could simply be ignored. Just as Herzl dismissed Yusuf Diya al-Khalidi’s letter, most later schemes for the disposition of Palestine were similarly cavalier. The 1917 Balfour Declaration, issued by a British cabinet and committing Britain to the creation of a national Jewish home, never mentioned the Palestinians per se, the great majority of the country’s population at the time, even as it set the course for Palestine for the subsequent century.

The idea that the Palestinians simply do not exist, or even worse, are the malicious invention of those who wish Israel ill, is supported by such fraudulent books as Joan Peters’ “From Time Immemorial,” now universally considered by scholars to be completely without merit. On publication in 1984, however, it received a rapturous reception and it is still in print and selling discouragingly well. The book was mercilessly eviscerated in reviews by Norman Finkelstein, Yehoshua Porath and numerous other scholars, who all but called it a fraud. Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg, who was briefly my colleague at Columbia University, told me that the book was produced by Peters, who had no particular Middle East expertise, at the instigation, and with the resources, of a right wing Israeli institution. Essentially, he told me, they gave her their files “proving” that the Palestinians did not exist, and she wrote them up. I have no way of assessing this claim. Hertzberg died in 2006 and Peters in 2015.

Such literature, both pseudo-scholarly and popular, is largely based on European travelers’ accounts, on those of new Zionist immigrants, or on British Mandatory sources. It is often produced by people who know nothing about the indigenous society and its history and have disdain for it, or worse yet have an agenda that depends on its invisibility or disappearance. Rarely utilizing sources produced from within Palestinian society, these representations essentially repeat the perspective, the ignorance and the biases, tinged by European arrogance, of outsiders. Such works are numerous. See Arnold Brumberg, “Zion before Zionism, 1838-1880,” Syracuse University Press, 1985, or in a superficially more sophisticated form, Ephraim Karsh’s characteristically polemical and tendentious “Palestine Betrayed,” Yale University Press, 2011. This book is part of a new genre of neo-conservative “scholarship” funded by, among others, extreme right-wing hedge-fund multimillionaire Roger Hertog. Another star in this neo-con firmament, Michael Doran of the Hudson Institute, is equally generous in his thanks to Hertog in the preface to his book “Ike’s Gamble, America’s Rise to Dominance in the Middle East,” Simon and Schuster, 2016.

The message is also well represented in popular culture in Israel and the United States, as well as in political and public life. American public attitudes on Palestine have been shaped by the widespread disdain for Arabs and Muslims spread by Hollywood and the mass media, as shown by Jack Shaheen in “Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People,” and by Noga Kadmon in “Erased from Space and Consciousness: Israel and the Depopulated Palestinian Villages of 1948,” which shows from extensive interviewing and other sources that similar attitudes have taken deep root in the minds of many Israelis.

The message has been amplified via mass market books such as Leon Uris’s novel “Exodus” and the Academy Award-winning movie that it spawned, works that have had a vast impact on an entire generation and that serve to confirm and deepen pre-existing prejudices. In her article “Zionism as Anticolonialism: The Case of Exodus” in American Literary History, 25, 4 (Winter 2013) Amy Kaplan argues that the novel and the movie played a central role in the Americanization of Zionism. See also chapter two of her book “Our American Israel: The Story of an Entangled Alliance, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018, pp. 58-93.

Leading American political figures have explicitly denied the very existence of Palestinians, as did former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich: “I think that we’ve had an invented Palestinian people who are in fact Arabs.” While returning from a trip to Palestine in March 2015, Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee said “There’s really no such thing as the Palestinians.” Similar views are strongly held by major political donors like the billionaire casino mogul Sheldon Adelson, the largest single donor to the Republican party for several years running, who has stated that “the Palestinians are an invented people.” To some degree, every U.S. administration since President Harry Truman’s has been staffed by people making policy on Palestine whose views indicate that they believe Palestinians, whether or not they exist, are lesser beings than Israelis.

Significantly, many early apostles of Zionism had been proud to embrace the colonial nature of their project. The eminent Revisionist Zionist leader, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, godfather of the political trend that has dominated Israel since 1977, upheld by Prime Ministers Menachem Begin, Yitzhadk Shamir, and Benjamin Netanyahu, was especially clear about this. Jabotinsky wrote in 1923: “Every native population in the world resists colonists as long as it has the slightest hope of being able to rid itself of the danger of being colonized. That is what the Arabs in Palestine are doing, and what they will persist in doing as long as there remains a solitary spark of hope that they will be able to prevent the transformation of ‘Palestine’ into the ‘Land of Israel.’”

Such honesty was rare among other leading Zionists, who like Herzl protested the innocent purity of their aims and deceived their Western listeners, and perhaps themselves, with fairy tales about their benign intention toward the Arab inhabitants of Palestine. Jabotinsky and his followers were among the few who admitted publicly the harsh realities that were inevitably attendant on the implantation of a colonial settler society within an existing population. Specifically, he acknowledged that the constant threat of the use of massive force against the Arab majority would be necessary to implement the Zionist program: what he called an “iron wall” of bayonets was an imperative for its success. As Jabotinsky put it in his article “The Iron Wall: We and the Arabs,” first published in Russian under the title “O Zheleznoe Stene” in 1923: “Zionist colonization…can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population — behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.” This was still the high age of colonialism, when such things being done to native societies by Westerners were normalized and described as “progress.”

The social and economic institutions founded by the early Zionists, which were central to the success of the Zionist project, were also unquestioningly understood by all and described as colonial. The most important of these institutions was the Jewish Colonization Association, renamed in 1924 the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association. This body was originally established by the German Jewish philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch and later combined with a similar organization founded by the British peer and financier Lord Edmund de Rothschild. The JCA provided the massive financial support that made possible extensive land purchases and the subsidies that enabled most of the early Zionist colonies in Palestine to survive and thrive before and during the Mandate Period.

Unremarkably, once colonialism took on a bad odor in the post-World War II era of decolonization, the colonial origins and practice of Zionism and Israel were whitewashed and conveniently forgotten in Israel and the West. In fact, Zionism — for two decades the coddled step-child of British colonialism — rebranded itself as an “anti-colonial” movement. The occasion for this drastic makeover was a violent campaign of sabotage and terrorism launched against Great Britain after it drastically limited its support of Jewish immigration with the 1939 White paper on the eve of World War II. This falling out between erstwhile allies (to help them fight the Palestinians in the late 1930s, Britain had armed and trained the Jewish settlers they had allowed to enter the country) encouraged the outlandish idea that the Zionist movement was itself anti-colonial.

There is no escaping the fact that Zionism initially had clung tightly to the British Empire for support, and had only successfully implanted itself in Palestine thanks to the unceasing efforts of British imperialism. It could not be otherwise, for as Jabotinsky stressed, at the outset only the British had the means to wage the colonial war that was necessary to suppress Palestinian resistance to the takeover of their country. This war has continued since then, waged sometimes overtly, but invariably with the approval, and often the direct involvement, of the leading powers of the day and the sanction of the international bodies they dominated, the League of Nations and the United Nations.

Today, the conflict that was engendered by this classic nineteenth-century European colonial venture in a non-European land, supported from 1917 onward by the greatest Western imperial power of its age, is rarely described in such unvarnished terms. Indeed those who analyze not only Israeli settlement efforts in Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the occupied Syrian Golan Heights, but the entire Zionist enterprise from the perspective of its colonial settler origins and nature are often vilified. Many cannot accept the contradiction inherent in the idea that although Zionism undoubtedly succeeded in creating a thriving national entity in Israel, its roots are as a colonial settler project — as were those of modern countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Nor can they accept that it would not have succeeded but for the support of the great imperial powers, Britain and later the United States. Zionism, therefore, could be and was both a national and colonial settler movement at one and the same time.

Why This Book?

Rather than write a comprehensive survey of Palestinian history, I have chosen in my latest book “The Hundred Years’ War” to focus on six key moments that were turning points in the struggle over Palestine. These six events, from the 1917 issuance of the Balfour Declaration, which decided the fate of Palestine, to Israel’s siege of the Gaza Strip and its intermittent wars on Gaza’s population in the early 2000s, highlight the colonial nature of the hundred years’ war on Palestine, and also the indispensable role of external powers in waging it.

I have told this story partly through the experiences of Palestinians who lived through the war, many of them members of my family who were present at some of the episodes described. I have included my own recollections of events that I witnessed as well as materials of my own and other families, and a variety of first-person narratives. My purpose throughout has been to show that this conflict must be seen quite differently from most of the prevailing views of it.

I have written several books and numerous articles on different aspects of Palestinian history in a purely academic vein. While this book is underpinned by academic research, it also has a first-person dimension that is usually excluded from scholarly history. Although members of my family have been involved in events in Palestine for years, as have I, as a witness or a participant, our experiences are not unique, in spite of the advantages we enjoyed because of our class and status. One could draw on many such accounts, and much history from below and from other sectors of Palestinian society remains to be related. Nevertheless, in spite of the tensions inherent in the approach I have chosen, I believe it helps illuminate a perspective that is missing from the way in which the story of Palestine has been told in most of the literature.

I should add that this book does not correspond to a “lachrymose conception” of the past hundred years of Palestinian history, to reprise the eminent historian Salo Baron’s critique of a nineteenth-century trend in Jewish historical writing. (Baron, by the way, was the Nathan L. Miller Professor of Jewish History, Literature and Institutions at Columbia University from 1929-1963, and is regarded as the greatest Jewish historian of the twentieth century. He taught my father, Ismail Khalidi, who was a graduate student there in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Baron told me four decades later that my father had been a good student, although given his unfailing courtesy and good nature, he may simply have been trying to be kind.)

Palestinians have been accused by those who sympathize with their oppressors of wallowing in their own victimization. It is a fact, however, that like all indigenous peoples confronting colonial wars, the Palestinians faced odds that were daunting and sometimes impossible. It is also true that they have suffered repeated defeats and have often been divided and badly led.

None of this means that Palestinians could not sometimes defy those odds successfully, or that at other times they could not have made better choices. But we cannot overlook the formidable international and imperial forces arrayed against them, the scale of which has often been dismissed, and in spite of which they have displayed remarkable resilience. It is my hope that this book will help recover some of what has thus far been airbrushed out of the history by those who control all of historic Palestine and the narrative surrounding it. □

Chapter 1: The First Declaration of War, 1917—1939

Chapter 2: The Second Declaration of War, 1947—1948

Chapter 3: The Third Declaration of War, 1967

Chapter 4: The Fourth Declaration of War, 1982

Chapter 5: The Fifth Declaration of War, 1987—1995

Chapter 6: The Sixth Declaration of War, 2000—2014

TO ORDER

“The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917—2017” will be released on Amazon on Jan. 28, 2020. Hardcover price is $30.00.

The Kindle version is $14.99.

The hardback version is also available from A.M.E.U. for $28.00, postage included. Send check to AMEU, 475 Riverside Drive, Room 245, New York, NY 10115. Or go to our website www.ameu.org and order through PayPal.