By Edward Dillon

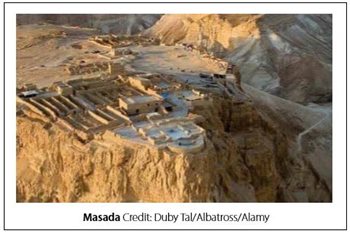

Some 65 miles south of Jerusalem stands an ancient mountaintop fortification overlooking the Dead Sea called Masada. Today, Israeli soldiers go there to take their oath of military service. It is also where tourists go, being the most popular tourist site after Jerusalem.

Masada was constructed by King Herod some 2,000-plus years ago, during the time Jesus lived. Palestine, as it was called, was under Roman occupation and Rome, like most occupiers, had its native insurrectionists to deal with.

One such group was the Zealots, Jews who believed that their god would deliver them from Rome’s pagan obscenities by means of the sword, thereby ushering in a worldwide Jewish theocracy. A splinter group of the Zealots was the Sicarii, assassins who concealed their daggers in their cloaks while mingling in a crowd and pulling them out to slash to death Romans — or even Hebrew Roman sympathizers — whom they judged idolaters.

To the Romans the Sicarii were terrorists to be hunted down and killed; to the Sicarii the Romans were blasphemers who had to be cleansed from the Temple precincts in preparation for the coming of the messiah, the promised deliverer of the Jewish nation.

The Romans eventually routed the Sicarii from Jerusalem, chasing them to Masada where, following a long siege of the fortress, the remaining fighters, along with their women and children — 490 in all — committed mass suicide.

Israeli soldiers, when they go to Masada, receive a gun and a Hebrew bible and pledge never to let Masada fall again.

For Christians there is a Sicarii connection. The apostle Simon is identified as a Zealot in Luke 6:15 and in Acts 1:13. And in the Garden of Gethsemane , when the crowd comes to arrest Jesus, one of his disciples pulls out a sword and cuts off the ear of the slave of the high priest, only to have Jesus reprimand the disciple saying “No more of this!” At which Luke adds “And he touched the slave’s ear and healed him.”

Violent or non-violent resistance to oppression, it’s a choice that reverberates down through the ages.

I. The Rabbi’s Response

I once heard someone ask a rabbi, “Rabbi, what do you make of the many texts in the Hebrew scripture where the God of Israel mandates the extermination of a neighboring tribe?”

The rabbi answered with a wave of his hand, “We don’t bother with those texts.”

He went on to explain: “Judaism is not a biblical faith. It is the rabbinic tradition of the covenant faith.”

He then added:

“The rabbis determined which texts are authentic expressions of that tradition and which texts are crucial and basic, providing a focus and prism though which to understand the other texts.”

Reflecting on these remarks, I have concluded that classical Christianity is similar. For the Orthodox and Catholic churches, Christianity is not a biblical faith. It is the apostolic and patristic tradition of the Christian life that matters.

The Christian canon of sacred texts was first expressed formally in 4th century Egypt by St. Athanasius, patriarch of Alexandria. The other churches, one by one, declared themselves in agreement.

Christians as a rule do not wave aside the terrible texts mandating genocide. We have come up with the explanation that goes like this: Sometimes we turn to scripture to find the truth about god. What we find instead is the terrible truth about us and the darkness from which we have come.

II. The Crucial Texts

In Judaism at the high holy days (the Days of Awe) texts from Isaiah are highlighted.

On New Year’s Day (Rosh Hashanah) the text of Isaiah 61 is read, proclaiming the Jubilee Year, so long expected: announcing liberty to captives, release to prisoners, a Jubilee Year from god.

On Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) Isaiah 58 is read describing the kind of fasting desired by god: releasing those bound unjustly, untying the thongs of the yoke, sharing your bread with the hungry, not turning your back on your own flesh.

It is amazing that the two gospels that attempt to give a coherent accounting of the teaching and ministry of Jesus are rooted in these two texts.

Isaiah 61 is the text read by Jesus at the beginning of his ministry (Luke 4:18 ff). Jesus then declares the text fulfilled in their hearing. The rest of Luke’s gospel (and volume 2 of the Acts of the Apostles) elucidate the meaning of that crucial text.

In Matthew’s gospel, the climax of Jesus’ teaching comes in chapter 25, the judgment scene. It grows out of Isaiah 58. “When did we see you, Lord, hungry and give you to eat, naked and clothe you, sick or imprisoned and visit you, away from home and welcome you?” And the response: “As long as you did it for one of these least ones, you did it for me.”

This convergence also shows how dependent the Christian movement was on the Jewish tradition of life and worship.

III. The Darker Texts

The darker themes also permeate the sacred texts: the god of the heavenly armies and holy war. These are the themes behind the notion of covenant and the chosen people. Originally “chosen” meant chosen warriors cleansed and consecrated for holy war: putting the rival tribes under the ban, marked for extermination.

This does not make Israel unique in this regard. It was state of the art for tribal warfare. The covenant of brotherhood bound clans and tribes together to fight holy wars.

The common religion of these nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes was henotheism: the worship of one god, while not denying the possible existence of other gods. God chose a particular tribe to show his strength and splendor against rival tribes whose gods had chosen them to show their strength and splendor.

The god of henotheists is a jealous god who becomes furious at betrayal, going over to a rival god.

Each of the tribal gods has chosen a special land for the chosen tribes and can be fittingly worshiped only in that holy land.

It took centuries for henotheism to become monotheism: the belief that there is only one god who wills to save all, a much more serene conviction.

It is doubtful whether many of us have moved from henotheism to monotheism.

It is doubtful, too, whether we have assimilated the empathy of the two chapters of Isaiah highlighted on the Jewish days of awe or the two gospels, Luke and Matthew.

The Liberty Bell in Philadelphia was commissioned for the State House by the founding Quakers. It contained the words from the book of Leviticus describing the Jubilee Year, central to both the Jewish and Christian vision. “Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

It’s cracked, of course, and hasn’t sounded in years.

It’s now an ironic symbol of our nation’s dreams and shortcomings.

IV. Political Zionism

In the early years of Zionism the problem of religion was rather simple: just get rid of it.

The first challenge for the Zionists was to free themselves from the tyranny of the rabbis. They were to identify themselves no longer as a religion, but as a people in search of a land of their own where they could be as Jewish as the English are English and the French are French.

Theodore Herzl’s choice won the day when he, as the father of modern political Zionism, sided with those who favored Palestine as their land. They loved to call it “a land without a people waiting for the people without a land.”

When I visited Palestine-become-Israel in 1965 to live in a kibbutz, first in the north and then in the south, I was told that seven out of eight of the kibbutzim were thoroughly secular, eliminating any trace of rabbinic usage or teaching. The other one-eighth was thoroughly rabbinic and observant.

The Labor Party that governed throughout the early years of the new state was solidly in control. It was secular, left-leaning and democratic — excluding those Palestinians whom Israel had failed to expel and who now were confronted with this new reality.

By the time Benjamin Netanyahu came to power in 1996, Labor was in a permanent decline. Now Likud was in charge, building less on the history of the movement and more responsive to racist fears of the stranger in their midst —the native Palestinians.

Netanyahu’s father, Benzion Netanyahu, had a visceral aversion to the Book of Isaiah, which he blamed for making the Jewish people passive and a victim people celebrating their victimhood. Nation-building, he maintained, was the driving force behind Zionism. People had to put aside victimhood and the kind of religion that celebrates it.

Luckily the younger Netanyahu found the perfect solution in highlighting the Book of Joshua as the new religious paradigm. This is the sixth book of the Hebrew Bible in which the god of the Israelites commands Joshua to take possession of the Land of Canaan — the Promised Land — and not leave alive anything that breathes, including men, women, and children. Today we call this genocide.

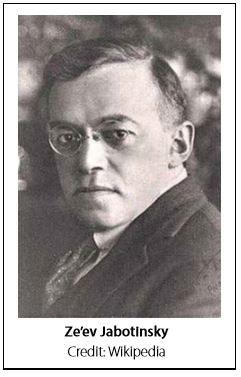

The warrior hero was always part of the Zionist program. In addition to learning how to work the land, build houses and towns, and govern themselves, Zionists had to learn to defend themselves. Ze’ev Jabotinsky, co-founder of the paramilitary group the Irgun, freely acknowledged that Zionism was a colonial enterprise in Palestine and Israel had to maintain an Iron Wall that Palestinians could never penetrate. In his 1923 essay The Iron Wall he wrote: “To think that the Arabs will voluntarily consent to the realization of Zionism in return for the cultural and economic benefits we can bestow on them is infantile.”

Even President Franklin Roosevelt knew that “A Zionist state in Palestine can only be installed and maintained by Force.” For that reason all Israeli citizens over the age of 18 who are Jewish are conscripted into the armed forces. For similar reasons, Arab citizens are not. Perhaps there is no more powerful symbol of Jabotinsky’s Iron Wall than that mountaintop fortress of Masada, where young Jewish men and women go to swear to fight to the death for the land they colonized.

Today some half million Jews have settled on Palestinian land in the West Bank and Jerusalem. And they have made it clear that they are there not as a temporary security measure, but as part of the realization of the Zionist desire to reclaim the land after two millennia in exile. Many of these settlers aspire to high positions in the Israeli army in order to ensure that should the Israeli government ever try to evict them, they would be able to countermand the orders.

Among Christians a similar shift in emphasis has taken place. Mainstream Protestants, with their humanitarian priorities, international concerns, and ecumenical education, were undermined by two “liberal” U.S. presidents (Woodrow Wilson and Harry Truman) and two mainstream Protestant theologians (Reinhold Niebuhr and Krister Stendahl). [See Don Wagner’s April-May 2016 Link article “Protestantism’s Liberal/Mainline Embrace of Zionism.”]

President Wilson, in the fall of 1917, was faced with supporting Britain’s Balfour Declaration favoring the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people or accepting the advice of his State Department to be true to his “Fourteen Points,” which guaranteed self-determination to majority populations in the Ottoman territories. He chose Britain over his State Department.

President Truman’s embrace of the Zionist cause was due in large part to pressures dictated by his 1948 reelection campaign. Again, rejecting the advice of his State Department that the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish States was unworkable, he promised that the United States would be the first country to recognize Israel. And so it happened, early in the morning of May 15, 1948, the United States recognized Israel eleven seconds after it became a state.

Reinhold Niebuhr, one of the most liberal Protestant theologians of our time, called the Palestine question morally ambiguous. Arabs, he argued, had several territorial homelands, while Jews had none. Jews deserved at least one geographic center, and Palestine was their best option. Niebuhr was aware of the ethnic cleansing of 750-800,000 Palestinians that occurred in 1948, and said nothing about it.

Krister Stendahl was a Swedish New Testament scholar and Harvard Divinity School professor who claimed that the Jews, as god’s primary “chosen” people, are intimately tied to the land of Palestine. A close friend of Stendahl was Rabbi David Hartman, founder of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. In March 2002, when a Palestinian suicide bomber killed 11 Israelis in Jerusalem, Hartman called for the extermination of all Palestinians: “Let’s really let them understand what the implications of their actions are. Very simply, wipe them out. Level them.” Stendahl faxed his friend seeking a meeting to discuss his painful words, but the rabbi never responded.

Eventually, mainstream Protestantism was replaced in influence and visibility by fundamentalist churches emphasizing the end times, final warfare, and the coming judgment and victory of the triumphant god and his Christ.

So, where might we find the most authentic Christian churches? According to the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who visited America in the 1930s, the tradition of the suffering Jesus was most authentically encountered in America’s black churches. Bonhoeffer saw first-hand the results of white supremacy in New York and throughout the Jim Crow south, so when he returned to Nazi Germany he had great empathy for Jews, homosexuals, and all the rest of Hitler’s “racial purity” victims.

Another group that deserves recognition is the American Friends Service Committee. Known as the Quakers, they believe that the presence of god exists in every person and they strive to repair the disorder caused by war and violence by relieving and healing its victims. Today, AFSC supports the campaign to divest from companies and corporations that benefit from Israel’s occupation. And it has had some success. For example, Friends Fiduciary has divested $900,000 from the Caterpillar Corporation, the company that sells Israel its armored bulldozers used to demolish Palestinian homes to make room for more settler construction. In 1947, AFSC accepted the Nobel Prize on behalf of Quakers worldwide.

On the other hand, the Catholic Church, as an institution, is no longer heard proclaiming the social justice teaching of earlier popes, but is now forced to respond to charges of long-standing cover-ups of clergy crimes against minors.

V. Going Along to Get Along

As noted, Benjamin Netanyahu and his allies turn to the book of Joshua and the heroic stories of conquest. The Palestinians are seen in the ignoble role of the Amalekites, a Canaanite tribe wiped out by Joshua. Indeed, some rabbinical leaders today cite the biblical injunction to exterminate the Amalekites as justification for expelling Palestinians from the land and even killing Arab civilians during warfare.

Meanwhile, the Isaiah wings of the Jewish and Christian traditions have another role for Palestinians: they are to be passed over in silence.

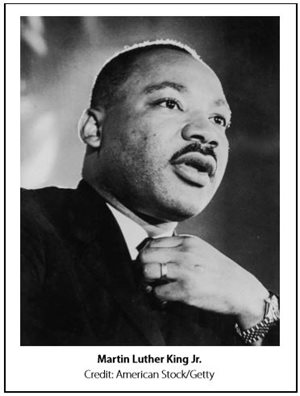

Michelle Alexander, in a Jan. 20, 2019 New York Times op-ed commemorating Martin Luther King’s birthday and legacy, reminds us of King’s sermon delivered one year to the day before his murder. It was given at New York City’s Riverside Church.

King confessed that his silence concerning his moral revulsion at the Vietnam War amounted to a betrayal of all the values wrapped up in the struggle for civil rights in his own country. Quoting the anti-war group Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, he announced: “A time comes when silence is betrayal.”

The silence of people of conscience about the intensifying suppression of Palestinian life in Israel, the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and especially in Gaza is the great moral shame of our time. We Americans, after all, are partially subsidizing this barbarism.

I have often agreed with people who say that it is not up to us Christians to level the charges against the Jewish state. We should still feel guilty for what we let happen to Jews in our lifetime. And we should leave it to Jews, especially in Israel, to lead the way in challenging the regime.

We have waited quite a while for that to happen. Many Israeli Jews have stepped into the breach. After Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon Yesh Gvul was heroic. Their name , “There is a Limit,” says it all. 500 officers resigned their rank making their livelihood in Israel dire indeed.

Even in the States many individual Jewish scholars and others have tried their best to bring Israeli behavior under traditional Jewish ethical scrutiny. Many were labeled self-loathing Jews or little better than Hitler. Their careers were blighted. I think of Dr. Norman Finkelstein and Dr. Marc Ellis.

What about our silence? What are we afraid of?

Are we even qualified to honor the legacy of Martin Luther King?

Let’s look at the past and the two classical ways a religious institution can diverge from its authentic tradition. The first is by watering down its tradition; the second is by withdrawing from the world.

The age of martyrs among the Jews extends from the early second century before the Common Era until the early to mid-second century of the Common Era, roughly 300 years. Under conditions of occupation, first by the Seleucids and then the Romans, believers were often required to publicly disavow their allegiance to God and Torah or die. The early heroes of this age were the Maccabees who struggled against the Greek-speaking tyrants of Syria, the most infamous of whom was Antiochus Epiphanes. The martyrs appeared here and there until the famous uprising led by Bar Kochba, around the year 132 CE.

However, even before the Bar Kochba uprising, shortly after the Roman destruction of the Temple in the year 70, rabbis had gathered at Yavneh, a coastal city some 12 miles south of Jaffa, to begin adapting Judaism to its new situation, an exercise that would become the basis for Jewish religious practice throughout the world, up to our own time. Conspicuously missing from the rabbis’ list of authentic writings to be included in the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings was most of the literature that promoted uprisings or celebrated martyrdom (like the Books of the Maccabees). Instead, their emphasis was to present the Jewish tradition as a timeless wisdom. Indeed, the earliest Roman historians (Tacitus and Suetonius) could describe Jews as a philosophical sect in Syria. This watering down of ethical principles eventually fostered a too cozy relationship with Roman rule, and led to the silent acceptance of Rome’s practice of slavery and its waging of licentious warfare.

The Christian version of this going along to get along was to withdraw from the world, and it stems from the same motive: to live in peace in the Roman world. The Christian response to the rule of Rome grew out of the Jewish response.

In the aftermath of the destruction of Jerusalem and all of Palestine, both Christians and Jews recognized that Roman rule was more in the vein of Persia under Cyrus the Great than like Assyria, Babylon or the Antiochian Syrians.

Cyrus introduced something new to world imperial strategy: Encourage the subject people to be faithful to their language and religion, their laws and their ways. The Persians even offered aid in returning to their ruined towns and rebuilding them. Pay taxes in a timely way and show respect for the great king and insignia of his reign.

After the Bar Kochba revolt, Roman persecution of Christians was sporadic and localized for the first three centuries of the Common Era.

The great persecution under the emperor Diocletian was different. It was worldwide and lasted 10 years (c. 300—310 C.E.). Diocletian had worked his way up through the military ranks to become commander-in-chief, i.e., the first Celtic emperor.

The Celts started as mercenaries fighting the Roman battles on the borders. Gradually they took over the empire, including the military, the civil bureaucracy and the church of the empire.

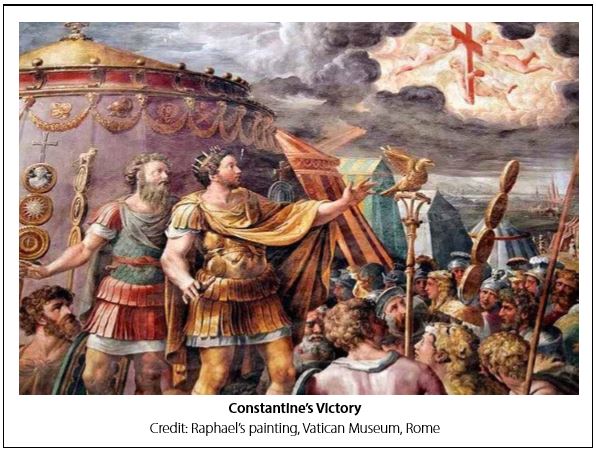

After Diocletian, Constantine fought in the name of Christ. The cross became a sword facing outward. With Constantine, Christianity became legal and, soon thereafter, the official religion of the Roman world, East and West. It also became intolerant of competing religions, and complicit with all the crimes of imperial Rome, including the vast amount of slaves in the empire.

In the 6th century, when the emperor withdrew for good from Italy and the West, the Patriarch of the West, the bishop of Rome, assumed the imperial role, including the imperial title, Vicar of Christ on earth. Slavery would still be endorsed, as would the Crusades, and the Inquisition.

Meanwhile, beginning in 4th century Egypt and Syria, life in the cities had become so violent and chaotic that Christians began moving out into the wilderness where they created islands of peace and order known as monasteries. In Europe thousands of towns grew up around these monasteries, where the rhythm of daily life echoed the rhythm of monastic life.

This shift in lifestyle was also based on the texts of Isaiah, especially chapters 40—55. This is the middle section of the Book of Isaiah, known as the Book of Consolation, written in the 6th century BCE, during the Babylonian exile. Just as monastic life was seen as a withdrawal from the world, so the Book of Consolation spoke of a people in the wilderness, awaiting God’s servant who will bring God’s justice to distant peoples not by shouting in the streets, but by nurturing the least signs of life: “The bruised reed he will not break, nor the smoldering flax quench,” says Isaiah 42;3; and “He was oppressed and afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth, like a lamb that is led to the slaughter,” says Isaiah 53:7.

For Christians this Suffering Servant is Jesus. In Galatians 2:20, St. Paul writes: “He loved me and gave himself for me.” And the author of “Hebrews” in 10:12 adds: “He offered himself once and for all to take away sins.”

No mention is made here of the power of Rome, or of the Roman procurator’s collusion with the high priest who had Jesus arrested, tortured, and executed as a terrorist for challenging their cozy arrangement.

Overlooked, too, is any reference to the text from Isaiah read on the Day of Atonement:

This rather is the fasting that I wish:

releasing those bound unjustly,

untying the thongs of the yoke,

setting free the oppressed,

breaking every yoke,

sharing your bread with the hungry,

sheltering the oppressed and the homeless,

clothing the naked when you see them,

and not turning your back on your own…

This is the text that is in sync with Gandhi’s non-violent resistance to evil and speaking truth to power.

This was the challenge of a lifetime for both Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Of course it led eventually to their deaths.

I remember when Malcolm X and Martin Luther King finally met and were able to compare their struggles? Malcolm said: “Martin, you and I have one thing in common.”

“What’s that?” asked Martin.

“We’re both dead men,” replied Malcolm.

That is fidelity to one’s beliefs, not going along to get along.

VI. The Resilience of Tradition

There is a wisdom tradition in the Hebrew writings that transcends any sectarian enthusiasm.

In the Book of Ecclesiastes there is the passage: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven.”

The lines that cause people to question it are:

“A time to kill and a time for healing”

“A time to love and a time to hate”

“A time for war and a time for peace”

People ask: How can there be a time to kill? Does this not contradict the Sixth Commandment handed down in stone by god himself?

We need to remember that the god here handing down the stone tablet is a henotheistic god, the god of a particular tribe, the Israelites, and that the Commandments were intended to enable members of the tribe to compete successfully against other tribes and their gods. Put bluntly, it’s not okay to kill a fellow Israelite, but it is okay for an Israelite to kill a member of a competing tribe, if done for a good cause. Today we call this the just war theory.

Still the question remains: How can you say, as the author does,: “He has made everything appropriate to its time, and has put the timeless into their hearts without their ever grasping, from beginning to the end, the work which god has done.”

It seems god is in charge of the seasons and our job is to recognize the season that is upon us and live it out as best we can.

Ask the policeman sent to stop the slaughter in the synagogue in Pittsburgh whether that was a time for him to kill. The killer had become furious when he learned that that synagogue was raising money to help the asylum seekers coming to our border with Mexico.

Consider the special forces service man sent to Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan. He — or she —will wage war, not because he is impressed by the motives of those back home who sent him into harm’s way, but to defend his comrades who have entered into battle with him.

It is impressive to see the unity of black people in our country, forging common ground across religious lines, Muslims and Christians. They can disagree about goals and strategies, but recognize comrades in the common struggle.

There is the same unity across party lines among Jews who work for civil rights.

The thing that unites us most is the spirit of compassion.

I see it in imams working in prisons who help out on any effort to better conditions for prisoners.

I see it in Jews who pitch in to help with support for any cause to help the oppressed and homeless.

I see it especially in women religious and other women in the Catholic community who are always on call for emergencies.

The single most impressive expression of compassion, to my mind, is the welcoming of asylum seekers by such countries as Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey: 2,000,000 apiece! The feeling of brotherhood among Muslims across sectarian lines is awesome.

I am heartened to hear that Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a hero of my youth, was transformed by his experience of faith in action as witnessed in America’s black churches. It moved him to return to Germany to join the resistance to Hitler. On his return he took with him dozens of recordings of back spirituals, which sustained him up to the day he was executed for taking part in a conspiracy to assassinate Adolph Hitler.

Keep our eyes on the Jubilee Year proclamation: “Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

VII. The New and the Old

In St. Matthew’s Gospel the author quotes Jesus as saying: “Every scribe learned in the ways of god (my translation) knows how to draw from his treasury of wisdom the new as well as the old.”

The new can turn out to be the old spruced up and viewed with fresh eyes. Thus when the Zionist dream took shape of a new land and a new beginning, they looked for texts that dealt with rebuilding the ruined cities and nation building: Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles, and the Deuteronomic history came to mind.

But the crucial texts of Isaiah read on the Day of Atonement and New Year’s Day always maintain the place of honor.

Catholic Christians hear these texts on Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent, the season of fasting and preparing for Easter. I’ve cited them twice in this article, but they bear repeating:

This, rather, is the fasting that I wish:

releasing those bound unjustly,

untying the thongs of the yoke,

setting free the oppressed,

breaking every yoke,

sharing your bread with the hungry,

sheltering the oppressed and the homeless,

clothing the naked when you see them,

and not turning your back on your own.

The words inscribed on the Liberty Bell taken from the Book of Leviticus still ring loud though the bell is cracked: “Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

The Book of Isaiah, as we have seen, describes what a Jubilee Year acceptable to the Lord would look like. St Luke, in chapter 4, verses18-19, uses that text to sum up the mission of Jesus:

The spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me, to bring

good news to the poor. He has sent me

to proclaim release to captives, and

recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are

oppressed, to proclaim the acceptable

year of the Lord.

This is the ecumenical mission of the Jews first, and then of Christians and Muslims — if we but take from our treasury of wisdom both the new and the old.

Readers who may have questions or comments concerning our feature article are encouraged to email them to ameu@aol.com. We will forward them to Ed Dillon who will respond to as many as possible.