Rawan Yaghi

“Whose bag is this?” he shouted.

I stepped forward and tried to smile. He smiled back as he opened my small suitcase and started poking his hands into it.

“Where are you going?” he asked, still smiling.

“Amman,” I replied, trying not to sound too hostile. I don’t know if my voice was too low, or my accent too unintelligible. “Where?” he repeated. “Amman”’ I said again, a bit louder, still trying not to sound aggressive. He smiled.

Rifling through my bag, he took out a carefully wrapped dish of Arabic Knafeh, a Gazan specialty, that my dad had bought for my aunt who was hosting me for a couple of days in Amman. He ripped a hole in the corner of the wrapping paper and poked his gloved fingers in. I kept silent. He took out my sneakers, rummaged through my underwear and my different items of clothing, still with a smile on his face, as I watched my hours of careful packing being destroyed. He finally declared: ok.

Leaving Gaza

The first time I was so graciously given permission to leave Gaza was when I had to go to Jerusalem for a visa interview at the American Consulate. As my father drove me to the Palestinian side of the checkpoint, I watched the gradually worsening infrastructure out the car window. Gaza is not big, but we drove through a lot of streets that I’ve never seen before. I’d definitely be lost if I went there alone.

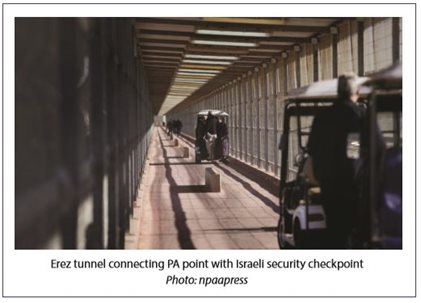

The Palestinian side of the checkpoint was divided into a Hamas point and a West Bank Palestinian Authority-affiliated (Fatah) point. At the Hamas checkpoint, I was interrogated as to why I’m exiting and who had arranged for me to do so. After they cleared me, I continued to the West Bank PA- affiliated point, which did the direct coordination process with the Israeli side. After handing over my ID card at a small window of a metal box-room, I sat in an open-air waiting room that had an asbestos roof and was surrounded by fences and barbed wire. It was connected to a long fenced tube that was the route to the Israeli point.

My name was finally called. I got my ID card back, said bye to my dad and started walking through the long tunnel. I felt the endless cameras watching me. I was conscious of what I was wearing — a long Jilbab and a scarf, covering all of my body except my face and hands — and I contemplated what a stupid decision it was to wear this for this occasion. And I wondered if the same thought was running through the soldier’s head as he watched me approach the Biblical Kingdom he saw himself protecting — possibly from the weapons he must think I’m hiding under my clothes. These nervous thoughts kept running through my mind but I managed to make it through that tunnel with a clear head.

There were gates, buttons to press, more gates, more buttons to press, before I finally encountered another human being. I imagined that I was in a science fiction movie, and somewhere behind the doors a robot would show up and sanitize my body before giving me a special outfit that would make me safe to interact with the regular inhabitants of that land.

Next, I encountered a man who was wheeling a cart. He was thin and spoke Arabic. He said I should take out any zaatar or pickles from my bag because the soldiers will force me back outside the security inspection area to throw them away, and then I’d have to go through everything again. I looked through my bag to make sure I had no such terror-related items, then followed the signs into a building that looked like a factory.

Inside, there were about two dozen closed lanes with only one near the end open. I walked towards the green light where I had to cross another iron gate. There I had to empty all of my possessions into a plastic tray that went behind a wall. I then had to step into a metal detector that had glass doors that closed behind me. Raising my arms in surrender, I was scanned for dangers to the other species. Finding none, it allowed me out into another maze of corridors, where my bag was manually searched after going through the invisible scanner behind the wall. It was then handed to me by a man in a uniform that was half military, half civilian. Everyone who was Israeli and worked at the checkpoint wore a beige t-shirt, black trousers, and army boots. Some handled computers or searched bags, while the rest had massive machine guns across their chests going down to their thighs. These roamed the place watching us, the Palestinians, sometimes chatting in Hebrew to the bag- searchers.

After receiving my bag, I was allowed to proceed to a line of glass cubicles which had at most two persons in them and which had narrow corridors in between. Was this the actual checkpoint? I wondered. Behind the glass, a woman with curly hair asked for my ID card. She looked at it and at me, then at it again, then at her computer screen, then at some papers, then at me, then at the ID, then at her computer screen, and finally handed me back the card along with the permit. It was a glorious permit — it would allow me to roam Israel from 5 AM to 7 PM — six hours of which had already passed. I was then allowed out of the narrow corridor to the other side, where I was greeted with a ‘Welcome to Israel’ sign. But there were still more iron gates to cross, more MK-47-wielding soldiers to pass before I walked out of the glass doors towards the final iron gate. Hearing their laughter behind me I hastened my pace. I was scared, angry, humiliated.

A couple of interviewees and I were met by a driver, a Palestinian, from the American Consulate. As we later learned, he had been instructed not to deviate from the route that goes from the checkpoint directly to the consulate’s door, and vice-versa on the way back. We had a few hours to be interviewed and nothing else. We were allowed to see Jerusalem from far away, through the car window, nothing more. I was taking everything in silently but another interviewee was excited and chatty. He begged the driver to take us to the old city. The driver explained that the car is tracked with a GPS and that he would be in trouble if he drove to the old city, but eventually he felt sorry for us, and so drove near a touristy area near one of the gates which was as far as he dared go. We saw tourists, predominantly white Europeans and Americans who, unlike us, were allowed here. After all the humiliation, it took begging a fellow Palestinian to take us close enough to get a cursory glimpse of a place we dreamt of going to since childhood: what should be the capital of our own country.

No one enters or leaves

I have now been abroad for four years as I finished my undergraduate studies. I am one of thousands of students, professionals, scientists, who are blessed with a Palestinian ID that classifies them as Gazans — and because of this Israeli-determined ID, we may not have been home since we began our lives abroad. We need Israeli permission to go home, and if we got it, we might never get Israeli permission to leave again.

It was when I walked through the Holocaust exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London that I sensed exactly what that ‘home’ was that I was going back to. On the wall a quote from Chaim Kaplan from the Warsaw Ghetto taken on 17 October 1940 read:

No one enters or leaves. Anyone who tries to flee risks his life. The guards of the ghetto do not permit the farmers from the villages to bring any food in through its gates.

This resonates with experiences of Palestinians dating back to 1948.

Gaza is a140-square-mile strip on the southwest side of Palestine. It has the Mediterranean Sea on the west, Israel on the north and east, and Egypt on the south. It has two points of entry for human beings, Erez in the north, and Rafah in the south. The idea that movement has become an issue only after Hamas took over is a myth. Movement in and out of Gaza has been difficult ever since Israel existed.

After Zionist militias ethnically cleansed over 760,000 Palestinians to Gaza and the rest of the world, the newly-created state of Israel locked up the Strip. Farmers who had fled or been pushed to Gaza ended up starving in what later were termed ‘refugee camps.’

Some of them wanted to go back to their lands to collect their crops, to dig out the money and gold they hastily buried thinking they would be back, or simply to go to Hebron where they thought there would be something to eat. There were no checkpoints; many were summarily shot when they approached the Armistice Line. Some who survived were taken prisoner, interrogated, and tortured. The vast majority of victims are lost to posterity, but among those whose story is known was Arafa Ahmed Abu-Saif.

Arafa was 18 when in 1950 he turned up in Wadi Araba, a desolate desert south of the Dead Sea, a survivor of what he and his 86 companions termed the March of Death. (Their testimonies are preserved in the National Archives, Great Britain, Kew, FO905/111.) An estimated 118 men of all ages and two girls had been captured by armed Israelis, imprisoned and made to walk through the desert into Jordan. One of the girls was shot while trying to escape the march, 37 of them died while trying to make the journey. These days, watchtowers and drones are on the job of keeping the prisoners inside. Anyone detected near Israel’s borders — though still in the West Bank or Gaza — risks being shot or blown to pieces.

At the end of the Holocaust exhibition, confronted by the white chalky recreation of Auschwitz, I ran out of the building in a panic. The idea that human evil could reach this level of cruelty suffocated me. But I did want to admit the similarities to what is happening back home: The wall around Gaza and through the West Bank are much like the fences, barbed wires, and walls erected in German-occupied Europe to keep out unwanted men, women, and children. As are the myriad ways to dehumanize, wound, and kill. As is imprisoning human beings in open-air prisons, controlling their every movement, being the supreme authority that dictates their lives.

And I remembered again Kaplan’s words.

I have always associated travelling with pain. My mother went to Egypt probably once in all the lifetime I’ve known her. She went for a medical operation. She’s kindly been granted permission to pray at Al-Aqsa only recently because she’s now over 55 years old. My father went to the West Bank for medical treatment only once since I was aware of my surroundings. I can’t remember my younger brother, 21, leaving the Strip other than when he was five years old. My older brother left after months of depression and failed attempts to leave via Rafah to study in Malaysia. My oldest brother, on the other hand, can sometimes travel between Gaza and the West Bank, because he’s a senior worker in a foreign NGO. But without such special circumstances, being Gazan means being trapped in our 140-square-mile prison.

The British journalist Robert Fisk, in his Pity the Nation, went to Europe to look for answers after witnessing the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Lebanon in 1982. He came to the conclusion that nothing can be compared to the level of devastation that befell the victims of the Holocaust. I agree with Fisk. What Israel is doing is a more studied way of devastating a people, of turning them into slaves, of mentally and psychologically wearing them down until they succumb, settling for whatever the abusing power wants them to settle for. I wonder how many people have been killed, not only by the tons of explosives and new weapons that Israel continuously uses Gaza as a laboratory for, but also as a result of the restriction of movement, of trade, of the entry of humanitarian supplies.

Yet — if this is largely driven by a need to dehumanize an Other, what would happen to Israeli society if suddenly we Others didn’t exist?

The Erez checkpoint in Gaza was constructed as part of Israel’s plan to exploit cheap Palestinian labor, the way it still does in the West Bank. In Gaza, checkpoints are the tool of control and humiliation which have enabled Israel to control a population of over 2 million people and exploit them as a captive market for its products.

Israel uses the siege of Gaza to funnel international aid money to buy Israeli products exclusively. By being the sole controller of what comes in and where it comes from, Israel makes sure that Gaza remains a closed market for its products. Before the 2008/9 attack, Israel tightened the siege so that no products were allowed in. I remember walking into shops and looking at empty shelves. It was this life-or-death need for food that forced Gazans to dig tunnels into Egypt. Right now Gaza is suffering from a debilitating electricity crisis. In May and June, Israel reduced the amount of electricity it provides Gaza, reducing the supply to less than four hours a day. This, in turn, has caused sewage to be directed untreated to the sea, severely polluting Gaza’s water and sanitation services.

Checkpoints at border crossings in Gaza are also a cruel way to turn needy individuals into collaborators. Cancer patients and people in need of medication and treatment in Israel, the West Bank, or elsewhere have been blackmailed to gather intelligence — all the more efficiently by using the siege to cripple Gaza’s own medical facilities and supplies. People literally have to choose between their own death, or that of their children, versus collaborating with the enemy.

Consider 26-year-old Fadi al-Qatshan, a Gazan who needed a heart transplant. His problem was he had to go into Israel to get it, because years of Israel’s blockade of Gaza had degraded the area’s medical services. But to go into Israel he needed a travel permit from Israel to attend the hospital in East Jerusalem.

For over a year Fadi submitted one request after another — all denied. Then, one day, he received a phone call from a man saying he was from the Shin Bet, Israel’s intelligence service. He told Fadi in Arabic that he knew the device in his heart “might explode any minute,” and that to get a new implant, all he had to do was “cooperate.” A phone number appeared on his mobile phone. Call it, the man said, and you can arrange an appointment at Erez, the Israeli-controlled crossing from Gaza into Israel.

Fadi never made that call, and he never made it to Jerusalem. In November 2013, the implant in his heart did indeed fail and the 26-year-old died in Gaza.

Not only do Israeli security forces play with the psychology of people, making them believe that their lives are dependent on a permit, they also use this power to break the society that is currently standing on a straw. Around the clock Israel works to make us suspect one another: What did my neighbor do to get that permit? Where did my other neighbor get the money to fix his house?

Rafah in the south of Gaza is not a commercial crossing and Egypt never allowed it to be, so the only way Palestinians could get their food and fuel was from Israel. Gaza was a captive market. Israel made sure it had no airport—bombed in 2001—or seaport from which it can export goods independently. So when the crippling economic siege was imposed in 2007, and tightened in the build-up to Cast Lead, prices went up, Israeli food and fuel stopped coming in. Nothing was allowed to be exported except carnations on a few occasions.

The Gaza Model was so perfect for Israel until we started to literally dig our way to the world. Tunnels went under Rafah to Egypt and allowed us to breathe a little. They were constructed mostly by young men who could not find another way to make a living, who would go underground and dig and attach supporting boards and hope the earth around them wouldn’t collapse on them.

The tunnels varied in size and in the products they transported. Some were big enough to bring in cars, others so small only a stooping person could fit through. And their number was impressive; in September 2013, when Egypt destroyed most of the tunnels, it put the number at 343. Hamas taxed these to bring in revenue and there was talk of officials becoming richer as a result. Still the tunnels provided food, gas, medicine — and humans, like Syrian refugees. My father rented a small apartment to a Syrian family that came into Gaza through one of the tunnels. All of this had a human cost. Egypt used gas and water to flood the tunnels regardless of whether anyone was working in them at the time.

Outright military invasions, rather than the routine strikes that rarely make the news, usually hit two to four years apart. These were always accompanied by a complete closure of the borders and a complete stop in the processing of permits to go through Erez. The first of these operations was Operation First Rain.

This happened soon after Israel staged its ‘retreat’ from the Gaza Strip in 2005, dismantling all of the Israeli settlements there in a show that globally portrayed the leavers as traumatized victims being forced to ‘give up’ their homes and land. I remember my family and I drove to one of the settlements after the evacuation and that nothing was left. Some of the houses were burned. There weren’t even any trees. I remember looking at the barren scene, not feeling any of the excitement that I thought I was supposed to feel. Relieved as we were of the presence of Israeli settlers and the Israeli soldiers who guarded them, we were actually more vulnerable. Israeli historian Ilan Pappe, in his book “The Biggest Prison on Earth,” put it this way: “Some access to the outside world was allowed as long as there were Jewish settlers in the Strip, but once they were removed the Strip was hermetically sealed.”

Then, In Jan. 2006, Hamas won the democratic parliamentary elections in Palestine, and Israel now had the green light to intensify its closure of Gaza. The assaults became more devastating. I remember that during Israel’s 2008/9 Operation Cast Lead, we had very little food at home and used it carefully. Sometimes we risked our lives to get bread from the bakery, which might be open for a few hours during a ceasefire. We sat in darkness every night counting missiles that were falling around us, literally waiting for our turn. During this 23-day attack, the borders were closed except to people with foreign passports who were allowed out though Erez. Nobody else. The same happened in 2012 with Operation Returning Echo.

In 2013, the British Consulate heard about my winning a scholarship to Oxford University to study linguistics and Italian, and invited me to Jerusalem for one of their scholarship events. They offered to help me apply for the permit I would need, and so I seized the opportunity to ask if they could get me an additional permit that would allow me the selfish indulgence of seeing my sister in the West Bank. As a carrier of a Gaza ID, permission to enter Jerusalem is strictly that, and does not extend to other Palestinian bantustans such as Ramallah, where my sister resides. They succeeded, and I took the bus from Jerusalem to Ramallah through the Qalandia checkpoint. I expected the bus to stop at Qalandia and had my permit in hand, but the bus didn’t stop. For some reason, this unnerved me. The woman next to me explained that the Israelis don’t care who goes out of Israel. Only who goes in. I spent a night and a morning with my sister, her husband, and two children. The next day they drove me to Qalandia.

It looks like a slaughterhouse. The corridors leading to the iron gates are extremely narrow. They perfectly fit a one-person-at-a-time line with no room for any movement either to the left or right. I was so nervous that I kept going through the metal detector with my phone either in my pocket or in my hand, as soldiers chatted behind a glass window and paid me no attention. I eventually gathered some sense and let go of my phone and passed through the metal detector. I then had to show the soldiers behind the window my ID and permit.

This is probably one of the most humiliating things about the checkpoint. The window has no opening through which one can hand in the papers. I had to hold it up against the glass for them to see and inspect. The soldier barely looked at my face. He frowned for a bit. I guessed it was the Gaza ID part, and then motioned something that meant ‘oh ok that makes sense’ and signaled me to go. I then had to look for the bus that went to Jerusalem and when I found it I got in and sat near the driver’s seat as he was to tell me when my stop would come up. As soon as the bus moved, I could then see the wall, the massive wall that now stood between me and my sister. The grey force pressed down on my chest and I burst into tears. I haven’t seen my sister since then.

I was waiting for the British Consulate to get back to me about my permit to go home for the summer holiday when the 2014 attacks — ‘Protective Edge’ as they called it — started. I flew to Jordan anyway on the 7th of July, after I had finished my preliminary examinations at Oxford. When I landed, I heard the news about the bombings. But I was still hopeful that I would get in. I called my family and they were ok. The Consulate replied to my email saying that the Israelis were not processing any permit applications at the moment. Egypt was also closed. I couldn’t do anything. I stayed in Amman, where my aunt lived, waiting as I watched on the news Gaza being bombed. My sister in Ramallah was perhaps a couple of hours’ drive, but she might as well have been on the moon. I didn’t have Israeli permission.

After a month and a half, the consulate replied about my going home to Gaza. Yes, the Israelis agreed to let me into the Strip. But no, they would not let me out at the end of the summer. My family was going through hell on earth and I was supposed to choose between my degree and being with them. Ilan Pappé described the attack of 2014 as “a police force entering a maximum security prison in which the prisoners are besieged and running their own lives; you control them mainly from the outside parameters and you put yourself in danger if you try to invade it, to confront the desperation and resilience of those you are trying to starve and slowly squeeze the life out of.”

Indeed, everything about Gaza suggests it’s a maximum security prison — though ‘prison’ is such a legally acceptable word. And in prison, inmates are provided with services like food, infrastructure, education, and sometimes even libraries. Gaza is left to itself and bombarded every few months to make sure the inmates are constantly traumatized, and to destroy all they build, plant, make a life out of.

In the summer of 2015, my family convinced me to try to go home as my brother was getting married in August. I therefore declined two summer internship offers, and headed to Jordan at the beginning of the summer vacation. My family had applied for a permit for me to go through Erez as Egypt was closed, and because the British Consulate decided it will only apply for a permit for me to go back in at the end of my studies. And since I left Gaza through Erez, I had to go back through there since Israelis have a rule about using the same point of entry and exit. I stayed in Amman for two months, waiting for a response that never came. Israel completely ignored the application. The coordination office kept coming up with excuses like ‘the person in charge is on holiday.’ No one ever answered my permit application. I missed both my brother’s wedding and a summer internship. That was the last time I decided I would try to go home during my studies.

Said’s Story

Before leaving the UK to start traveling home, I took a train from London, where I had been staying with friends, to Oxford where I arranged separate meetings with different Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank.

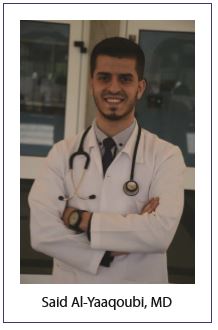

Maybe it was fear of what he would tell me that made me so nervous when I waited for 25-year-old Said Al-Yaaqoubi, who had just returned from Gaza and knew the situation with its checkpoints. I had met Said two years before when he came to Oxford for his elective program at the John Radcliffe Hospitals, a prestigious location sought by medical students worldwide. Students from Gaza who were nominated to go to the same program last summer and this summer, such as Mohammed Radi, were not able to make it as Israel blocked them from leaving. Said finished his studies in medicine at the Islamic University of Gaza and was accepted in a number of Masters programs in British universities, among which were Durham and the University of Oxford. With no hesitation, he accepted the offer funded by the Centre for Islamic Studies in Oxford to do a course in Integrated Immunology.

When he arrived at the café, I stood up and nervously shook hands. We chatted about my plans to go home, but he thought they should not have been an option in the first place. “There is nothing there,” he warned. “You have no idea how difficult the last few months have been for everyone. They suffocated us.”

I did not know how to respond.

Maybe the reconciliation will make things easier?” I asked, trying to sound more comfortable with my decision to go home.

“The reconciliation means nothing. It’s bullshit. Gaza will never be included in any long term solution. Therefore, nobody wants to take it over. This means that the only way to keep it going is by keeping it at a minimal cost [for Israel, the PA, and Egypt], by pushing people there as far as possible, and getting them used to it as well.”

He knew I wanted to know the current situation with the checkpoints. I asked what happened while he was trying to get out. Said took a deep breath.

“I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t concentrate on my job. Everything in my life was focused on trying to get out of the Strip. Even conversations with fellow medics were about borders and possible ways of getting out. I could not afford a break.”

In June, he applied for a permit to leave the Gaza Strip via Erez, the only Israeli checkpoint where travelers may be allowed out.

Said did not hear anything about his permit application for three months. Weekly, the visa office in Oxford contacted the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), to enquire about his permit but with no results. The Israelis ignored them and kept postponing a decision on his application.

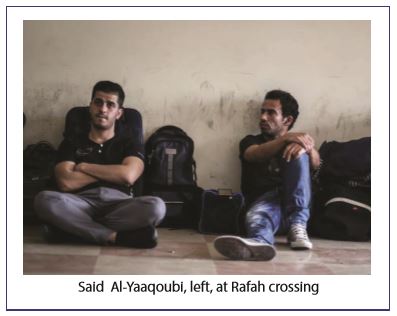

His other option was the Rafah crossing, a border crossing with Egypt situated at the southeast corner of the Gaza Strip, for which he registered at the Ministry of Interior in Gaza. The list of travelers is endless. This year, the border had only been opened a few times, until news about the reconciliation started to come out. When it was open it was for three or four days at most. In mid-August, the crossing was open for two days. Said’s name wasn’t on the list but he hastily packed a few things and went to the border. There, he spent two days on the floor, waiting for some sort of a miracle to happen. Said described the situation at the border as desperate. He said he was pushed and shouted at. He said the number of people in desperate need to leave is incredible, thousands at the border who were pleading. Everyone was under pressure and the security men and employees of the border control were losing patience.

Said even tried the method used by those who are desperate enough and can find a way to afford it. It is called ‘tansiq.’ A word loathed by most Palestinians, it is a euphemism for—bluntly put— bribes to crossing officialse to be given priority to be included in the list, issued every few months, of names allowed to cross. The word surfaced with the emergence of the –also loathed—Oslo accords in 1993. The process, according to Said, is very shady and feels “like you’re dealing with some sort of a Mafia. I paid 3,500 US dollars to a mediator based in Gaza who would then give a certain percentage of that money to his partners. There are about a dozen mediators who do this kind of job in Gaza.

The amount of money paid could range from US $1,000 — already a crippling amount of money for a family of average income in Gaza—to $10,000, a year’s worth of full monthly salaries for a regular employee. The level of service travelers get at the crossing corresponds to how much ‘tansiq’ they paid. Usually, the higher price the traveler has paid, the more respectfully they are treated and the less hassle they face at the border. The amount also decides whether the traveler is sent straight to the airport or allowed into Egypt. This was not the image I remember of Gaza when I left at the age of twenty. But it does not surprise me.

Apparently, the deal between Hamas and the officials at the border was to allow the exit of 1,000 travelers each day, half of whom are tansiq travelers and the other half are regular people whose names were registered at the Ministry of Interior in Gaza. On 28 August 2017, there were about 100 patients who required medical treatment abroad. The Palestinian employees thought they could push the 100 on top of the allowed 500 given they are patients and the Egyptians might take pity on them and allow them out. This did not work. The Egyptians did not allow the 100 to leave, sticking by their numbers. The patients were turned back to Gaza.

Said was supposed to get out on the opening of 27/28th of August, according to his mediator. The first day, his name did not come up. His mediator kept promising him that his name will come up the next day. It did not. Apparently it was a scam. Said recalled: “At this point, I started to lose it. I maximized my efforts, contacted everyone, someone told me to post about it on Facebook. I did. People from all sorts of organizations and places started to contact me.

On 29 August, I contacted Gisha, an Israeli, not-for-profit organization founded in 2005 to protect the freedom of movement of Palestinians, especially in Gaza. They said they will follow up on the old permit application. They did and apparently the Israelis were still not going to let it through. Nearing the end of September, and hence the start of my course, Gisha decided to take it to court in Israel since there was absolutely no reason they shouldn’t allow me out. However, I didn’t want it to be taken to court. I didn’t want my name to have a court record with the Israelis and I didn’t want it to drag on for another month. Gisha said it’s just an intimidating tactic. The Israelis always avoid going to court because the judge will not find a reason I shouldn’t be allowed out and therefore will rule in my favor and then they will be forced to let me out.”

That worked. Said continued: “The Israelis called me for an interview at Erez, after which either the Israeli court or the Israeli military should let me in. I headed to the border the next day. Hamas said I needed an approval from the Ministry of Interior first. I was about to lose my mind. I went to the Ministry of Interior. The person to sign my approval would not come in until 9 am. My interview was supposed to be at 8 am. My nerves were on the breaking point. After a great deal of questioning, I was given signed approval and immediately headed back to the border.”

“After an interview there, I went back to Gaza. That day I was extremely tired, I went home and slept for hours. It was the deciding moment. They had to get back to me within two days, otherwise we would have to take it to court and have it drag on for another month, beyond the start of my course, which would risk me losing my place this year. While I was asleep, I had received many missed calls from Gisha and a text message saying I am to be allowed out the next day. I couldn’t believe it.”

After his bags were rummaged through, Said was left to wait at Erez while everyone else was allowed through to the ‘coordination’ bus, a bus of about 50 passengers from Gaza who had applied for permits independently or were coordinated for by other organizations. They were escorted by three Palestinians from the PA coordination office and they made sure the 50 would be taken from checkpoint to border and nowhere else in either Israel or the West Bank.

Said waited for 30 minutes of nerve wracking silence on Israel’s part. When he was finally called and let through, he grabbed his bag and ran to the bus. Before entering the bus, all passengers had to hand over their permits and passports to the two PA escorts. They are only given back their documents at the Allenby Bridge near Jericho.

At the Israeli checkpoint of the Allenby Bridge, Said was stopped again. He was asked to have a seat and wait. Again, he was put through a very stressful 90 minutes where nobody spoke to him about what was going on and where the checkpoint got emptier and emptier. Even the PA escorts left. “At this point, I thought they were going to arrest me. I thought, if the escorts won’t take me back to Gaza and the Israelis won’t let me in, then they want to put me in prison for no reason. I was in contact with one of the other people on the bus, a woman from Gaza going to study at Oxford Brookes. She had reached Amman by that point. I lost hope.”

After the two-hour wait, an officer came to speak to him. Said continued: “The officer asked me what I did and told me that a lot of people in his family were medics. He was smiling and joking the whole time. And I was forcing myself to do the same. But I was so nervous and stressed. I was literally about to lose my mind. When he finished his chat, he gave me my passport and said that I was free to go. I almost ran out of the hall. From then on, everything went smoothly. I arrived in Amman and all I was thinking of was just going to my room in Oxford and sleeping for a long time. I didn’t want to wait in Amman, I didn’t want to wait in London even. When I arrived here I was tired for such a long time. It took me about ten days to recover.”

And on the West Bank…

Gaza is only one part of the story. The West Bank, chopped up into bantustans, is also an open air prison.

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker organization that promotes peace through justice. In May, 2014, it sent a delegation to visit the West Bank. Martha Yager, program coordinator for AFSC’s Southeastern New England office, was part of that delegation. On her return in July, in a blog published by AFSC, she described what she saw.

The occupation, she wrote, was “violent” and “unpredictable.” She cited two reports, a Feb. 2014 report by the Israeli human rights organization, B’Tselem, and a Dec. 2013 report by the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The B’Tselem report counted 99 fixed checkpoints, 40 on the border with Israel and 59 inside the West Bank; the OCHA report counted 256 flying checkpoints, these are checkpoints that pop up sporadically across the West Bank. All these checkpoints are run by the Israeli military. They snarl traffic and limit movement. Treatment is arbitrary; often people wait for no reason at all. According to OCHA, more than 2.4 million people are affected by these physical restrictions in the West Bank.

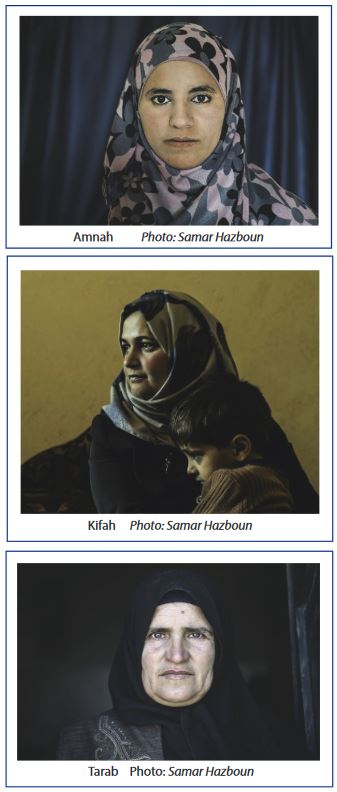

In her photo essay “Beyond Checkpoints,” Samar Hazboun, a Palestinian photographer, has documented cases of Palestinian women who have given birth at Israeli checkpoints, or who have been delayed for hours before being permitted to cross and go to a hospital.

There is Amnah, 19, who woke up at 6 am to birth pains and left the house with her mother for the hospital. Upon arriving at a checkpoint, they were held for five hours by Israeli soldiers. Amnah’s mother tried to explain her daughter’s situation as she was bleeding heavily, but the soldiers refused to let her through. By the time they were able to take another route to reach the hospital, the baby had died in Amnah’s womb.

Kifah was pregnant with her first child when around 4 am she felt birth contractions. In order to reach the hospital, she and her husband had to cross a checkpoint, but were denied permission to pass. As her husband tried to convince the soldiers it was urgent his wife get to the hospital as quickly as possible, Kifah fell to the ground and began to give birth. As soon as the baby’s head appeared, the soldiers let them cross to the other side where an ambulance was waiting. Kifah gave birth to her son at the checkpoint, causing him irreparable brain damage.

Tarab was eight months pregnant and bleeding heavily when she was prevented from crossing a checkpoint with her husband at 4 in the morning. Her husband decided to try another route to the hospital, but faced yet another checkpoint where they again were denied crossing. A puddle of blood started forming under Tarab’s seat as her husband tried negotiating with the soldiers. Finally they were permitted to cross, but only on foot. Tarab’s husband carried her onto a cart and pulled her as he walked towards the hospital. Shortly after their arrival, they were notified that the baby had died in Tarab’s womb 30 minutes before reaching the hospital.

For a period of three years (2008-2011), The Lancet, a United Kingdom medical Journal, worked with Palestinian health professionals and researchers to document the stress caused by these checkpoints, especially the terror inflicted on women delayed at checkpoints waiting to give birth. Halla Shoaibi, now in the Law Department of Birzeit University, in the West Bank, worked with The Lancet researchers. She noted the terror of these women was well-founded. During a seven-year period (2004-2011), 69 babies were born at Israeli checkpoints—35 of them died, as did five of the mothers, an outcome which lawyer Shoaibi considers tantamount to a crime against humanity.

How Long?

People in Palestine have indeed been resilient but I don’t know what other choice they might have had over the past years. News about the reconciliation government has had mixed reactions. There are those who are anxious, like me. There are people who are just relieved that some of the pressure will finally be lifted, that Hamas will no longer rule. There are people who are skeptical like Said, which is the majority of young people.

For a long time, we thought that Israel’s long-term plan was to get rid of the Palestinians, to drive them out by any means possible. In Gaza, they’ve tried everything. They’ve starved, bombed, intimidated, detained, destroyed infrastructure, robbed water, polluted the air, cut off medicine and trade. They created the perfect model for psychological and physical control of a state over a people. Pappé calls it the Ultimate Maximum Security Prison Model. In the West Bank, Israel has created the same level of control.

Yes, Palestinians have shown a great deal of steadfastness and self-restraint, but many of them have chosen to leave because the situation is getting ever more intolerable. They’ve chosen to not keep their lives on hold. Maybe it is forced emigration in another form. Pushing people to a point where Palestine becomes a place associated with trauma and imprisonment. Said’s experience convinced him that he can never go back to Palestine. But if Israel barely allows anyone out, how are we meant to leave?

Israel no longer uses Gaza as a source of cheap labor. It does continue to use it as a laboratory for its updated weapons. Sometimes, I even wonder if they use press footage of our destroyed houses, burned bodies, and torn limbs as advertisements for the efficacy of their products in marketing their advanced weapons. Wherever you look, you can find traces of a sick social and psychological experiment.

Really, we ask ourselves, What does Israel want from us Palestinians? And for how long?

Editor’s Note: On Dec. 11, 2017, as we were going to press, Rowan sent me this email:

Yesterday, on my return to Gaza, at Erez, an Israeli woman said my DSLR 1200D Canon camera wasn’t allowed in. I offered to show her the photos I had taken. A uniformed official then came by to say I could take the body of the camera but not the lens. I explained that the body was useless without the lens. He went back to his office and returned with a piece of paper and said I could call the number on it to see if I can get the lens back. I asked if I could reclaim my lens the next time I exited Erez. He said no.