By Jonathan Cook

Perhaps it was fitting that the most significant act of organized mass resistance by Palestinians to the occupation in many years was launched from behind bars. In April of this year more than 1,500 political prisoners began an indefinite hunger strike against their increasingly degrading treatment by the Israeli authorities. Some called it a prison “intifada,” the word Palestinians use for their serial efforts to “shake off” Israeli oppression.

Over the past five decades, Israel’s incarceration industry is reported to have locked away some 800,000 Palestinians, amounting to 40 per cent of the male population. At any moment, there are few families that do not have at least one close relative in jail.

More generally, Palestinians often characterize the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank as giant prisons. Checkpoints, permits, walls, fences, settlements, Jewish-only roads, closed military areas and blockades restrict movement so severely that most Palestinians are effectively confined to open-air cells of varying size. The Israeli historian Ilan Pappe’s latest book, a history of the occupied territories due out this summer, is titled “The Biggest Prison on Earth” for that very reason. An act of mass defiance by Palestinian prisoners resonates far beyond the concrete walls of Israel’s three dozen detention centers.

Israel’s treatment of Palestinian prisoners has significantly deteriorated in recent years, with only cursory objections from the International Committee of the Red Cross. A surge in Palestinian inmate numbers over the past 18 months – to 6,500 detainees – has brought the prison population to levels not seen since the early years of the second intifada, some 15 years ago. Overcrowding has pushed the mood among political prisoners to a boiling point.

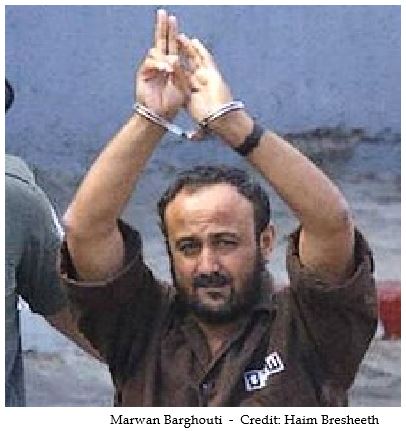

The hunger strike, under the banner “Freedom and Dignity,” was initiated by Marwan Barghouti, the most senior Palestinian official behind bars. One of the leaders of the ruling Fatah movement and the head of its armed resistance at the start of the second intifada, he was sentenced to multiple life terms following his capture in the West Bank in 2002. He has since become the figurehead of the Palestinian prisoners. But more significantly, his status has grown to almost mythic proportions during his long years of incarceration, making him the most popular contender to succeed the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas. He is possibly the only Palestinian leader who has the power to unify the Palestinians under occupation in the way the late Yasser Arafat once did.

At the time of writing it is too early to know what course the hunger strike will take. It could lead to the deaths of prisoners, even Barghouti himself, and the eruption of a new intifada. Or Israel could make enough concessions that the prisoners either relent or split sufficiently that the strike becomes ineffective. It has not helped that the prisoners have struggled to attract much visible concern from the international community. As Arundhati Roy, the award-winning Indian writer, has observed, all acts of non-violence, including hunger strikes, work only as spectacle, or theatre. It “needs an audience. What can you do when you have no audience?”

For this reason, it has been difficult for the Palestinians to find an auspicious moment to conduct mass protests. The world’s attention has been elsewhere: on Cairo’s failed Tahrir Square uprisings and the re-consolidation of military rule in Egypt; on the catastrophic fallout from the proxy wars across Israel’s northern border, in Syria; on Washington’s revival of a Cold War with Russia; and most lately, the drama of the US elections and the arrival of a wealthy reality TV star in the White House.

But there are reasons why Barghouti has invested his energies in promoting what Palestinians call “the battle of the empty stomachs.”

Not least, political prisoners face increasingly degrading conditions – a plight that resonates deeply with the Palestinian public. Among the demands are a halt to Israel’s frequent use of detention without trial, and its routine use of torture and solitary confinement as punishment; an end to lengthy and difficult transport between prison and court hearings, when inmates spend hours in the back of sweltering vans without food or water, and are forced to urinate into plastic bottles; the installation of pay phones so that inmates can maintain contact with their families, who increasingly struggle to get permits into Israel for visits; the opportunity to pursue academic studies while in jail, as well as greater access to TV and other media, rights Israel has overturned in recent years; and treatment in hospital, rather than prison clinics, for those with serious medical conditions.

But beyond the justice of the prisoners’ cause, the hunger strike offered a disillusioned, divided and weary Palestinian populace a model of how again to struggle against Israel’s oppressive rule. It offered a kind of struggle that might ultimately unify them.

Journalism as ‘terror attack’

Barghouti explained the reasons for the hunger strike in an opinion piece smuggled out of his cell and published in the international, though not domestic, edition of The New York Times. It was a publishing coup that enraged Israel. One government minister, Michael Oren, likened it to a “journalistic terror attack.”

The Times’ article was a rare break in Barghouti’s enforced silence. Since the Oslo process was initiated in the early 1990s, he is known to have continued as a supporter of the two-state solution, winning him allies on the Israeli left. But his ideas about how to achieve Palestinian statehood appear to have undergone a significant revision during his time in jail.

As one of the leaders of the armed uprising that began in late 2000, he was originally a fervent supporter of the right of Palestinians to use violence to liberate themselves from the occupation, though he stated that armed resistance should take place only in the occupied territories. Since then, watching events unfold from his prison cell, he has become a leading advocate for new strategies of non-violent resistance. His article in The New York Times offers insights into his changed thinking.

The refusal of food was, he wrote, a protest against Israel’s system of “mass arbitrary arrests and ill-treatment of Palestinian prisoners” – many of them at the forefront of the armed Palestinian struggle against the occupation. Israel, he added, had constructed an “inhumane system of colonial and military occupation [designed] to break the spirit of prisoners and the nation to which they belong, by inflicting suffering on their bodies, separating them from their families and communities, using humiliating measures to compel subjugation.”

Underscoring the point that the thousands of Palestinians currently in Israeli jails are suffering only a more severe form of confinement than their families outside, he continued: “Freedom and dignity are universal rights that are inherent in humanity, to be enjoyed by every nation and all human beings. Palestinians will not be an exception. Only ending occupation will end this injustice.”

In line with his new approach, he described the hunger strike as “the most peaceful form of resistance available. It inflicts pain solely on those who participate and on their loved ones, in the hopes that their empty stomachs and their sacrifice will help the message resonate beyond the confines of their dark cells.”

Barghouti noted his own, typical experiences of detention, including at age 18 being beaten on the genitals during an interrogation. His tormentors mocked him, saying it would be better if he did not have children because Palestinians “give birth only to terrorists and murderers.” He defied his captors, although he was again behind bars when his first son was born. Qassam was named for Izzeldin al-Qassam, the leader of the Palestinian revolt against British rule in Palestine in the late 1930s. Qassam would begin his own rite of passage in an Israeli jail shortly after his 18th birthday.

Barghouti, aged 59 and a father of four, has served most of his sentence in Hadarim prison, not far from the Israeli coastal city of Netanya. But in an attempt to break up the hunger strike, the Israeli authorities immediately transferred him to another jail, Kishon, near Haifa, where he was placed in solitary confinement.

All but one of the prisons holding Palestinians are located inside Israel. This is a serious, though rarely mentioned, violation of international law, which defines the transfer of prisoners out of occupied territory as a war crime. As Barghouti observed, by moving Palestinian prisoners out of the occupied territories Israel has been able to “restrict family visits and to inflict suffering on prisoners through long transports under cruel conditions.” He speaks from bitter personal experience. He is allowed to see each of his four children once a year on average, and has never been permitted to see his grandchildren because they are not “first-degree relatives.”

Despite Israel labeling Palestinian prisoners “terrorists,” Barghouti noted that the occupation army can seize anyone: “children, women, parliamentarians, activists, journalists, human rights defenders, academics, political figures, militants, bystanders, family members of prisoners. And all with one aim: to bury the legitimate aspirations of an entire nation.”

Once arrested, imprisonment is largely a foregone conclusion in a military court system enforcing “judicial apartheid.” Inside prison, Palestinians “have suffered from torture, inhumane and degrading treatment, and medical negligence.” As many as 200 prisoners have died because of such abuses since 1967, wrote Barghouti. He himself has been placed in isolation more than two dozen times in the past 15 years – a punishment the U.N.’s special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, wants banned as “cruel and degrading.”

Comparisons with Mandela

Since his jailing in 2002, Barghouti has been repeatedly described as the Palestinians’ Nelson Mandela, the black African National Congress leader who led the long and ultimately successful struggle against South Africa’s apartheid regime. It is a comparison he has been understandably happy to cultivate in a Palestinian national movement that is, at present, desperately short of icons.

In his New York Times article, he called the hunger strike part of the Palestinians’ “long walk to freedom,” the title of Mandela’s autobiography. He also noted that the International Campaign to Free Marwan Barghouti – backed by eight Nobel peace laureates, including former U.S. president Jimmy Carter and South Africa’s Archbishop Desmond Tutu – was launched four years ago from Mandela’s former cell on Robben Island. His wife Fadwa, a lawyer, has been a pivotal figure in the campaign.

Barghouti has not concealed his political ambitions, which are intimately tied to his prison activism. Early last year, he announced that, should the increasingly unpopular Abbas step down, he would enter the succession race from his prison cell. In a related document released by friends, he derided the Palestinian president’s signature policy of pursuing peace talks with Israel while campaigning for statehood at the United Nations. “This is a pathetic policy disconnected from the reality on the ground,” he wrote.

He criticized the Palestinian Authority’s “security coordination” with Israel, and the failure to reach a reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, the rival Islamic resistance movement that rules Gaza. He singled out Abbas for his authoritarianism, corruption, weakness and refusal to cultivate a new generation of leaders in Fatah. The political vacuum created by Abbas’ policies, Barghouti warned, had encouraged support for extremist Islamic groups among some youth and spawned the so-called lone-wolf intifada, a spate of disorganized stabbings and car rammings by individuals since late 2015. Barghouti urged “a revolution in the education system, in the way we think, in culture, and in our legal system.”

Concurrently, the Times of Israel website reported that Barghouti had reached a secret agreement with jailed Hamas and Islamic Jihad leaders for a renewed Palestinian struggle, this time drawing on the principles of popular non-violent resistance espoused by Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi. The plan, to be implemented after Abbas’ departure, is for a “People’s Peaceful Revolution” to pressure Israel into withdrawing from the occupied territories and conceding a Palestinian state.

The website reported that the participants had “agreed on having Palestinian civilians block all access roads to settlements, via an influx of Palestinians onto the main roads; damage to the infrastructure of the settlements, such as electricity, telephone and internet; and organized mass protests across Jerusalem. … Other steps laid out for the campaign are aimed at damaging Israel’s image in the world and its ability to continue ruling over the West Bank and even East Jerusalem.”

Qadura Fares, a senior figure in the Palestinian Prisoners’ Association and a friend of Barghouti’s, has expanded on such thinking: “The idea is to mobilize hundreds of thousands of people, who will march to Jerusalem. Another way is for tens of thousands of people to sit on the bypass roads [in the West Bank] from dawn to sunset. … I am talking about an intensive popular revolution that will disrupt the settlers’ lives. … We will sit on the road. Someone wants to have a wedding celebration? It will be held on a bypass road.”

Barghouti is reported to have devoured books on the history of non-violent struggle while in prison. According to his lawyer, Elias Sabbagh, Barghouti believes the only obstacle to this new strategy is the absence of an Israeli partner. “No [Charles] de Gaulle or [F. W.] de Klerk has yet arisen in Israel,” he told Sabbagh, referring to leaders who oversaw the end of French colonial rule in Algeria and apartheid in South Africa.

Israel’s nightmare scenario

The hunger strike clearly reflects Barghouti’s preference for acts of collective non-violent resistance. Israeli analysts have long warned that mass civil disobedience – the disruption of the occupation’s smooth running – is the Israeli military’s nightmare scenario. It was therefore entirely expected that Israel would seek to crush the protest. The leaders were put into isolation, while prisoners refusing food were denied family visits, dispersed to different jails, and barred from contact with their lawyers. Gilad Erdan, the minister of Internal Security, Strategic Affairs and Hasbara, told Army Radio: “These are terrorists and incarcerated murderers … My policy is that you can’t negotiate with prisoners such as these.” Erdan and other ministers have applauded the hardline response of the British government to a hunger strike by Provisional IRA prisoners in the 1980s that resulted in the deaths of 10 inmates, including Bobby Sands.

In a further sign of panic, Israel turned its fire on The New York Times, threatening to shut the paper’s bureau in Jerusalem as punishment for publishing Barghouti’s article. On Facebook, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu fumed against the paper: “Calling Barghouti a ‘political leader’ is like calling [Syria’s Bashar] Assad a ‘pediatrician’ [sic – he meant ophthalmologist]. They are murderers and terrorists.” Behind-the-scenes pressure led the paper’s editors to include online a footnote post-publication, “clarifying” that Barghouti had been convicted of “five counts of murder and membership in a terrorist organization.” They also allowed Erdan to write a response that used the term “terrorist” and “terrorism” no less than 18 times.

Despite Israel’s alarm, this is not the first time Palestinian prisoners have refused food. In the years before Arafat and the Palestinian leadership were allowed to return from exile in 1994 under the terms of the Oslo accords, such protests were used sparingly, and usually short term. Since Oslo, collective action by prisoners has proved more difficult to organize. During the second intifada, western audiences were generally more sympathetic to Israeli deaths than to protests by Palestinians defined by Israel and much of the media as “terrorists”. And then for the past decade, Palestinian politics has been scarred by a territorial and ideological split between Abbas’ Fatah party in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza.

Israel has inflamed these tensions in prison by giving Hamas detainees worse conditions than Fatah inmates, especially in relation to family visits and spending allowances in canteens. According to early reports, Barghouti struggled to win over Hamas prisoners to the strike, apart from those with him in Hadarim. And there was the further difficulty of controlling the largely non-affiliated prisoners arrested for their part in the so-called “lone-wolf intifada.” But by early May, there were reports that leaders from all the Palestinian factions had begun refusing food, in an indication that the strike was spreading.

Israel has reason to be deeply concerned by the potential of mass actions like the hunger strike. Barghouti may have hoped to tap into that longing for new forms of collective action. Palestinians have grown increasingly frustrated by the terminal impasse in negotiations, and by the failure of their leaders to unite. Even if the strike ultimately proves unsuccessful, it presents Palestinians with a timely alternative model of protest, when the idea of Israel as an apartheid state is gaining ground. The danger for Israel is that a hunger strike could inspire other forms of civil disobedience by wider Palestinian society.

The power of protest

It is not difficult to understand why a hunger strike appealed to Barghouti. The handful of prisoners who have in recent years refused food – mostly individuals detained without trial – have deeply embarrassed Israel, and in a few cases managed to extract an early release from the authorities. Israel has been so discomfited by the pressure of these isolated protests that it passed legislation in 2015 empowering prison authorities to force-feed inmates, despite objections from the United Nations and human rights groups that force-feeding constitutes torture. The World Medical Association has also barred doctors from forcibly feeding prisoners since 1975.

As the legislation was being voted on, minister Erdan equated hunger strikes with “a new type of suicide terrorist attack through which [prisoners] will threaten the State of Israel”. Notably, Israel quickly established “field hospitals” in the grounds of its main prisons, in what the inmates assumed was preparation for their force-feeding. At the time of writing, in early May, as some prisoners started to grow weak, the Israeli health ministry warned doctors that if they refused to force-feed striking inmates it would be their responsibility to find a replacement who would do so. Other reports suggested that Israel was considering flying in foreign doctors to force-feed prisoners.

Not only does a hunger strike challenge head-on Israel’s industrialized system of incarceration, but it has the potential to draw almost the entire Palestinian population into a highly charged confrontation with Israel. Too many families have a loved one at risk of death.

Whether the strike is maintained, succeeds or peters out, it hints at the latent power in Palestinian collective action – a power that has gone largely untapped since the mass civil disobedience of the first intifada in the late 1980s. It reminds Palestinians of their strength in numbers, of the complicity of their official leadership in Israel’s system of security control, and of their ability to disrupt the well-oiled machine of the occupation by direct action. A “battle of the empty stomachs” – this or a future one – could unleash a wave of civil disobedience and non-violent resistance outside the prisons. That could strip away the obfuscatory security pretexts employed by Israel, laying bare the occupation’s colonial nature.

Further, despite the decade-long split between Hamas and Fatah, the two movements are aware of the pressing demands from the Palestinian public for them to resolve their differences. Both have been damaged by the discord. Prison makes the ideological and strategic differences between Fatah and Hamas – differences Israel has richly exploited – far less relevant. Acts like refusing food offer a platform of resistance both factions can unify around. And unity is a precondition for Palestinian struggle to be effective, as Qadura Fares of the Prisoners’ Association has noted. The prisoners’ struggle “opens a door to the start of a popular intifada for Palestinian national unity and the rights of the Palestinian people.”

From his cell, Barghouti has repeatedly tried to push for unity. In 2006, in the immediate wake of Palestinian elections in which Hamas triumphed, he and leaders from rival factions published the so-called Prisoners’ Document calling for reconciliation and creating a political platform shared among the main factions for a two-state solution. A year later, he helped to broker the Mecca Agreement, which urged the various factions to put aside their differences and form a national unity government. Months later, the deal was torpedoed when the feud between Hamas and Fatah led to the Islamic movement taking power in Gaza.

As previously noted, there are reports that Hamas leaders have agreed with Barghouti to shift the struggle in the post-Abbas era to non-violent resistance. The unveiling by Hamas in May of a new charter – replacing one from 1988 – is a further sign of that ideological evolution. The new document jettisons the anti-semitic rhetoric of the original, severs historic ties with the Muslim Brotherhood movement and concentrates on Hamas’ role in a national struggle rather than a religious one. It accepts the Palestinian Authority as a vehicle to “serve the Palestinian people and safeguard their security, their rights and their national project.” Most importantly, while rejecting the “Zionist entity,” it declares Hamas is prepared to accept “a formula of national consensus” that would establish a “a fully sovereign and independent Palestinian state” in the occupied territories only. This brings it close enough to Fatah to make reconciliation – under Barghouti, if not Abbas – a real possibility.

Barghouti’s ambitions to bring Palestinians together has only served to intensify the Israeli authorities’ desire to keep him locked up. As Uri Avnery, a veteran leader of Israel’s small peace movement, has observed: “A free Barghouti could become a powerful agent for Palestinian unity, the last thing the Israeli overlords want.”

Unsurprisingly, most Israeli analysts cast a largely cynical eye on Barghouti’s role in the hunger strike, arguing that this was nothing more than a move to strengthen his credentials as Abbas’ successor. As evidence, they noted that privately Abbas is discomfited by the strike, even if official statements have been supportive.

Certainly, Abbas’ increasingly authoritarian and sclerotic rule in the West Bank has opposed any signs of popular resistance and the emergence of grassroots movements. Abbas’ security forces regularly prevent protests in the main cities, where Israel allows the Palestinian Authority, a supposed government-in-waiting, to operate most vigorously. Israeli journalist Shlomi Eldar was told by a senior source in Fatah that Abbas’ security forces had been “ordered to allow only modest demonstrations in support of the hunger strike” in the hope that the lack of visible solidarity would starve the protest of momentum. Despite the restrictions, Palestinians staged regular rallies, marches and protests in support of the prisoners.

Exploiting Abbas’ difficulties, Netanyahu called on him to stop paying salaries to “terrorists” in Israeli jails shortly before the Palestinian leader met U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House in early May. Republicans in the U.S. Congress, meanwhile, were reported to be drafting legislation to condition American aid – worth roughly $500 million annually – on the PA halting payments to political prisoners, and possibly their families too.

In Abbas’ view, he needs both to prove to Israel and Washington that he is a “responsible” leader who can maintain order and deserves the chance to lead a state, and to dissipate popular anger against the occupation in case it quickly turns against the Palestinian Authority and its complicity in Israel’s repression.

A Palestinian icon emerges

Barghouti’s long imprisonment has fueled the growth in his stature, both among Palestinians and in the international community. Paradoxically, his very absence has in many ways made him more visible.

Barghouti alone among the Palestinian leadership has not been tarnished by the national liberation movement’s catastrophic failures of the past 15 years. First, the vision of Palestinian statehood – either in its truncated Oslo form, or its much less accommodating Islamic version – floundered on the rocks of the armed intifada. Then it slowly sank into the dark waters of international indifference. Uniquely, Barghouti, locked away in an Israeli cell, could not be blamed for any of this. It is worth briefly plotting the dramatic changes to the Palestinian landscape since Barghouti disappeared from view.

Yasser Arafat, the man who did more than anyone to create a united Palestinian struggle for nationhood, died in mysterious circumstances in 2004. Many assumed he was assassinated by Israel, with Washington’s blessing. Both had grown frustrated by his failure to deliver their goal: autocratic rule over a series of Palestinian Bantustans that guaranteed quiet for Israel and its colonizing population in the settlements.

Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas, looked more to their liking. He not only forswore the armed resistance of the second intifada that Barghouti was so closely associated with, but then refused to replace it with any other form of popular struggle. In fact, quite the contrary. Abbas’ primary commitment has been not to resistance but to security coordination with Israel – effectively allowing Israel to co-opt the Palestinian security services as a subcontracted police force. Abbas has described that role as “sacred”.

Whatever his failings, Arafat understood the precarious nature of Palestinian struggle – and most especially the need to maintain a loose balance and consensus between the various Palestinian factions to prevent tensions reaching dangerously explosive levels. But the consensus prioritized by Abbas was one forged in Washington – and thereby implicitly in Israel. The change of strategy to near-absolute accommodation with the occupying power quickly brought long-standing grievances to the surface, particularly from Hamas.

Strains between Fatah and Hamas surfaced most strongly in Gaza because that was the one place in historic Palestine where Israel briefly gave the Palestinian movement a little room to breathe. The so-called disengagement of 2005, Israel’s withdrawal of its soldiers and settlers from Gaza, was followed a short time later by a Palestinian general election – one that, to the consternation of Israel and Washington, was decisively won by Hamas. Abbas continued to rule in the West Bank, now with a deeply compromised mandate, and paid little attention to Hamas’ political demands. In Gaza, the friction exploded into violence in 2007, as Hamas swept to power.

The consequence was a central fissure in Palestinian strategy and territory that remains to this day. Aided by Israel, Abbas’ Fatah movement entrenched its rule in the West Bank against Hamas, becoming more obviously authoritarian and repressive. And in Gaza, Hamas created a tiny Islamic fiefdom, a toehold from which it aspired to much greater things. A vision of Palestinian statehood – either of the diminished (Fatah) or comprehensive (Hamas) variety – faded as the two factions greedily protected what little they had, both from each other and from Israel.

Fatah sought to disband its armed groups and invested its energies instead in the diplomatic arena. Both the popular and armed struggles were renounced in favor of lobbying western states at the U.N. over statehood and issuing threats to pursue Israel for war crimes at the International Criminal Court. Western governments – those that had allowed Palestine’s colonization over many decades – were treated as though they could now be trusted to act as honest brokers between the Palestinians and Israel.

Gaza, meanwhile, suffered under a double hammer blow. On the one hand, it faced a long-term war of attrition through an Israeli-enforced siege of the enclave to starve the population into submission. And on the other, it endured a succession of vicious Israeli attacks that devastated Gaza’s infrastructure and killed and maimed thousands of Palestinians in each round.

Israel’s combined policy of isolating and intermittently pulverizing Gaza was more successful than is often acknowledged. Hamas’ fiery rhetoric became more hollow, then largely evaporated. It fired fewer rockets itself and then became more repressive in preventing other groups from firing them. Its problems only intensified as Egypt’s generals restored their rule in 2014, and blamed Hamas for aiding the Islamic opposition. Gaza lost its only partial access to the world through its border with Sinai.

As a result, Hamas in many ways came to mirror the compromises of Abbas’ Fatah movement in the West Bank. It sought quiet from Israel by enforcing quiet in its own territory on Israel’s behalf.

The Palestinian leaderships have not been entirely insensitive to the damaging effect of these changes on their credibility. But their efforts at unity have repeatedly failed for the simple reason that the structural conditions engineered by Israel and the U.S. encourage discord and feuding between the two factions, not compromise or unity.

While the national movements have turned into hollow shells, Barghouti has remained an icon of better times. Prison has maintained him as a perfectly preserved relic from another era – a golden era, when Palestinian leaders were seen to be with the people, offered a vision, and personally struggled for national liberation. Barghouti is a fighter unbowed, a hero, a Nelson Mandela waiting his moment. He is a blank canvas on which Palestinians can pour their dreams and hopes.

Awaiting assassination

Barghouti was the topic of one of the first commentaries I wrote after arriving in the region as a reporter. It was published by the International Herald Tribune, a daily now know as the International New York Times. My piece was published in September 2002 under the title “Marwan Barghouti: A Nelson Mandela for the Palestinians?.” My analysis was prompted in part by a commentary Barghouti had written earlier, in January of that year, for the Washington Post. Fatah’s general secretary on the West Bank and a member of the Palestinian Legislative Council, he was one of the leaders of the then 15-month-old armed struggle of the second intifada.

Reading Barghouti’s article now, one can see both how little has changed for the Palestinians in terms of their dilemmas, and how rarely their leaders speak today with the kind of forthrightness Barghouti employed then about the right to resist. The 2002 article also offers a revealing counterpoint to the commentary Barghouti published 15 years later in the International New York Times. It indicates that, locked in Hadarim prison, Barghouti has had the time and distance to rethink the nature – if not the aims – of the Palestinian struggle. It also suggests that, unlike those outside prison active in Hamas and Fatah, he is not trapped in a damaging turf war.

In his 2002 commentary, Barghouti pledged his commitment to two principles: a peaceful resolution of the conflict based on the two-state solution; and the harnessing of violence to force Israel to make the concessions needed for peace. The article serves as a difficult balancing act, trying to appeal to two very different constituencies. Barghouti hoped to maintain the relations he had cultivated with the Israeli left while at the same time satisfying a Palestinian public exasperated by the Israeli leadership’s bad faith.

He wrote of the Oslo process: “Since 1994, when I believed Israel was serious about ending its occupation, I have been a tireless advocate of a peace based on fairness and equality. I led delegations of Palestinians in meetings with Israeli parliamentarians to promote mutual understanding and cooperation. I still seek peaceful coexistence between the equal and independent countries of Israel and Palestine based on full withdrawal from Palestinian territories occupied in 1967 and a just resolution to the plight of Palestinian refugees.”

But he noted that Israel’s intransigence was backed by U.S. arms designed to crush any resistance to the colonization of Palestinian territory. “If Israel reserves the right to bomb us with F-16s and helicopter gunships, it should not be surprised when Palestinians seek defensive weapons to bring those aircraft down. And while I, and the Fatah movement to which I belong, strongly oppose attacks and the targeting of civilians inside Israel, our future neighbor, I reserve the right to protect myself, to resist the Israeli occupation of my country and to fight for my freedom. If Palestinians are expected to negotiate under occupation, then Israel must be expected to negotiate as we resist that occupation.”

He added: “I am not a terrorist, but neither am I a pacifist. I am simply a regular guy from the Palestinian street advocating only what every other oppressed person has advocated — the right to help myself in the absence of help from anywhere else.”

That “regular guy” image is a strong part of Barghouti’s appeal. But it was also why he expressed fears in the article that his days were numbered. Israel had tried to assassinate him the year before, when it fired on a convoy of cars, killing his bodyguard. He pointed out that in the previous 15 months some 82 Palestinians leaders had been killed in “targeted assassinations” – Israeli extrajudicial executions. He assumed he would join them. His commitment to resistance, he wrote, “may well lead to my assassination.”

As I noted in my subsequent commentary for the Tribune, Barghouti was wrong. He was not to be a victim of Israel’s assassination campaign. Instead Israel launched a daring military raid into the West Bank in April 2002 to capture him alive.

‘Don’t liquidate him’

Barghouti’s reprieve struck me as strange, even as a relative newcomer covering the conflict. But I was more surprised that Israel then chose to make a show trial of Barghouti rather than subject him to a military tribunal in which much of the evidence would have been heard in secret. As I wrote at the time: “He is on trial, surrounded by the world’s media, charged with terrorism offenses. He is unique among Palestinian resistance leaders in being given months in which to make his case in the three languages he has mastered — Arabic, Hebrew and English — to his target audiences: the Palestinian people, the Israeli left and world opinion. … His lawyers will be able to portray him as the real leader of Palestinian resistance to the occupation. In the eyes of the Palestinian people, he will end the trial an imprisoned hero.”

It is worth recalling that at the time Barghouti was taken captive his popularity did not extend far outside his Fatah circles in the West Bank. He was certainly no icon. All that changed during his trial.

It now appears I was far from alone in my suspicions. In a lengthy profile published in Haaretz in 2016, Israeli security officials and politicians recounted their surprise at the decision to capture Barghouti alive. It was Benjamin Ben Eliezer, the then defence minister, who overruled the generals’ plans to kill him. “I don’t want him liquidated – just arrest him,” Ben-Eliezer told a disgruntled military chief of staff, Shaul Mofaz. A captain involved in the undercover operation told the paper he believed the order “was a directive of the prime minister, Ariel Sharon.”

Afterwards, the justice minister at the time, Meir Sheetrit, proposed televising Barghouti’s court hearings “like the Eichmann trial” – Eichmann being a leading Nazi war criminal, who Israel managed to capture in Argentina in 1960. Ami Ayalon, a former head of Israel’s domestic intelligence service, the Shin Bet, said the trial made no obvious sense. “If I believed in conspiracy theories, I would think that possibly it was an Israeli conspiracy aimed at forging a leader who believes in the two-state solution,” he told the paper. Yossi Beilin, one of the architects of the Oslo process, concurred. “The trial was a mistake. Even the presiding judge, Sara Sirota, thought it was wrong. The trial turned him into Mandela.”

It is possible that Israel believed it could use the trial as a way to discredit Barghouti, to prove that he and Arafat were implicated in what Israel then grandly called the “infrastructure of terror.” But if that was their intention, they not only failed to make their case against Barghouti, they also grossly misread the wider political context. Barghouti’s stock rose throughout the trial, among Palestinians, international solidarity activists and even to a degree among Israel’s left. He leapfrogged more visible Palestinian leaders, including the Hamas spiritual guide Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, who would soon be assassinated, to become the main political rival to Arafat himself.

When Arafat departed the scene, Barghouti stood alone as his natural heir, a more credible choice than Abbas, who was derided by Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon at the time as no better than a “plucked chicken.” If Israel had wanted to make an icon of Barghouti, as Ami Ayalon noted, they could not have gone about it more effectively.

A long walk to freedom?

Possibly I contributed in a small way to the Mandela comparison with my commentary in the International Herald Tribune. Today, calling Barghouti a “Mandela” is meant to convey his credentials as a former “terrorist” turned peace-maker and reformer, as a bridge between two warring communities, and as the credible leader of a people seeking self-determination. His youngest son, Arab, meant it that way when he told Israeli journalist Gideon Levy recently: “My father is a terrorist exactly like Nelson Mandela. To the Israelis I want to say: If you admire Mandela, you should know that my father is repeating Mandela’s story.”

Back in 2002, however, I intended the comparison to be understood slightly differently. Mandela was held in jail to serve as a trump card if the apartheid regime ran out of steam. He was an escape hatch, providing an option for the white government to switch direction if international isolation grew too fierce. Back in 2002, it seemed that Barghouti could offer similar opportunities for Israel if its back was against the wall. The failure of the second intifada was not yet clear, and the Israeli economy and public morale was creaking under the strain of Palestinian resistance, especially the suicide attacks.

It is worth considering how Israel might have thought it could benefit from keeping Barghouti in jail rather than killing him. Just as South Africa eventually “rehabilitated” its own trouble-maker, Israel may have pondered a similar fate for Barghouti.

My argument at the time was that the Israeli army and the Shin Bet were deeply unsure of the second intifada’s endgame, especially in a period before Washington provided an alibi with its own, similar abuses in Iraq. In those, more difficult days for Israel, prime minister Sharon had to create increasingly improbable pretexts for refusing to engage with Arafat, including his infamous “seven days of quiet” before Israel would talk to the Palestinian leadership. The goal was to be rid of Arafat, but what would come next? Military assessments were that Hamas or even Islamic Jihad would emerge triumphant – as indeed the former did in the 2006 Palestinian elections.

Israel’s security services, I noted in 2002, might “need to engineer the emergence of a popular, pragmatic and non-Islamist Palestinian strongman to take charge of the West Bank and Gaza. Barghouti could fit the bill. He is not tainted by corruption or by suspicions of collaboration with Israel or America.” The task, on this assessment, would have been to break Barghouti’s spirit in jail but cultivate his image to the outside world as an independent Palestinian leader. Then if the moment arose, Barghouti could make his “long walk to freedom,” to rule over whatever fragments of a Palestinian state Israel conceded.

Crystal-ball predictions are notoriously unwise. But aside from whether this assessment of Israeli intentions was right or wrong, it is important to understand why it seemed plausible at the time – not least, because it reveals much about what has changed in Israeli calculations.

It is the job of intelligence services everywhere to prepare for multiple scenarios, including ones that never materialize. Shortly after Barghouti’s arrest, Sharon and his deputy, Ehud Olmert, began formulating the “disengagement” from Gaza and the related, if widely-forgotten, “convergence” plan for the West Bank. That would have created a bogus Palestinian state out of slivers of the West Bank and all of Gaza. That phantom state, which Israeli policy was directed towards achieving for several years, would need a leader.

A section of Israel’s political and security elite harbored such hopes for Barghouti at the time. According to Haaretz, the Labor party’s Ehud Barak, who had recently lost the premiership to Sharon, called the military chief of staff, Shaul Mofaz, incredulous at the decision to imprison Barghouti. He warned it only made sense “if it’s part of a grand plan to make him a future national leader of the Palestinians. … He will fight for the leadership from inside prison, not having to prove a thing. The myth will grow constantly by itself.”

Today, Barghouti still has a few supporters in the Israeli security establishment who cling to the idea of a two-state solution. Yitzhak Gershon, an army commander closely involved in Barghouti’s capture, has said recently: “He should be released unconditionally at this point. And not as a collaborator with us, but as someone who will see to the [future of the] Palestinian people. … Peace is made with powerful enemies whose honor has not been trampled.” Similarly, former cabinet minister Haim Ramon has told Haaretz: “There is no doubt that he will be the next Palestinian president. He’s the consensus. He is very much accepted by Hamas. When that happens, strong international pressure will be exerted on Israel, which will be forced to release him.”

However, such voices have been largely sidelined in Israel. Ehud Olmert, Sharon’s successor, shelved the convergence plan after he found himself politically weakened by criminal investigations and after the Gaza withdrawal exposed the fragility of the Palestinian national movement, opening up new possibilities for divide and rule. Ultimately Olmert was ousted by Benjamin Netanyahu, who had other ideas of what to do with the Palestinians.

Today, Barghouti appears largely surplus to Israeli requirements. Carmi Gillon, a former director of the Shin Bet who now heads the Peres Center for Peace, has said: “There is nothing to release him for now, because there is no momentum toward an agreement.” Israel no longer has an interest in unifying the West Bank and Gaza, or installing a Palestinian leader of a “converged” Palestinian state. The hunger strike of 2017 and his advocacy of confrontational non-violent resistance underline that Barghouti now poses more of a threat than a benefit to Israel.

Leading the second intifada

Barghouti was born in a village close to the West Bank city of Ramallah in 1959, as Palestinians were still digesting their massive dispossession a decade earlier during the Nakba. He was just eight years old when, in 1967, Israel captured the rest of historic Palestine. By 15, as the occupation entrenched, he had joined Fatah and was one of the founders of its youth movement, Shabiba. Three years later he was jailed, spending four years behind bars on charges of belonging to what was then defined by Israel as an illegal organization.

He put the time to use learning Hebrew, the language of the occupier, as most of his generation of local political activists did. In 1983, he began a history and political science degree at Bir Zeit University, near Ramallah, and was elected head of the student union. A year later he married a law student, Fadwa Ibrahim. However, he had to break off studies in 1987 with the eruption of the first intifada.

Barghouti took a prominent role in the early planning of the popular uprising. His current ideas about non-violent resistance are doubtless rooted in the lessons learned from the campaign of civil disobedience that characterized the initial stages of the first intifada.

Among the actions organized by Palestinians were protest marches, the closing of roads, boycotts of Israeli goods, the burning of ID papers, resignations from government and police positions, the refusal to pay taxes, and general strikes. Israel closed hundreds of schools to prevent youths from organizing, forcing Palestinians to set up “underground” classrooms. Meanwhile, popular committees were established to create an alternative welfare system, providing health services, childcare, education and food, to reduce the Palestinian public’s dependence on the occupation authorities. In one notable example of civil disobedience, highlighted in the 2014 feature film The Wanted 18, a Palestinian village created its own secret dairy plant, hiding the cows from the Israeli authorities, to end their reliance on Israeli milk supplies.

The first intifada occurred before Arafat and the other leaders in exile were allowed to return from Tunisia in 1994. Instead, the Palestinians in the occupied territories relied on a diffuse leadership. Barghouti was among those seized pre-emptively by Israel in 1987 and expelled to Jordan. He was only allowed back under the terms of the Oslo accords seven years later. Like most in Fatah, he was a strong supporter of the new peace process, even if he remained skeptical of Israel’s good faith. He cultivated contacts with Israelis in the peace camp, while rising through Fatah’s ranks in the West Bank. He was elected in 1996 to the new Palestinian parliament, the Legislative Council, and proved his independence by launching a campaign against human rights abuses by Arafat’s security services and corruption in the Palestinian Authority.

But with the collapse of the Oslo process in 2000, Barghouti was forced into a reassessment. He foresaw that another intifada was coming and correctly believed it would combine elements of the first intifada’s popular resistance with new forms of military struggle.

Insiders and Outsiders

Barghouti’s popularity among the Palestinian public has to be understood partly in the context of what is sometimes referred to as the split between Palestinian “insiders” and “outsiders”. Barghouti was one of the home-grown leaders, raised either in the West Bank or Gaza, who earned their stripes fighting on the front lines in the period before the Oslo accords. The “outsiders,” epitomized by Abbas, were the Palestinian leaders in exile, an elite who had often grown rich in Jordan, Lebanon and later Tunisia as they directed the struggle from afar. After their return in 1994, they imposed their rule on local leaders, often insensitively and with little experience or understanding of Israel’s machinations.

“The Tunis group viewed us as soldiers, and Marwan wanted them to see us as partners,” Qadura Fares observed. “He had been deported and was familiar with both worlds, so he was acquainted first-hand with the huge disparity between the standard of living of the leadership in Tunis and the poverty in the territories. He fought for equality and democratization. He worked to integrate people from the territories into the PA apparatus.”

The Tanzim, a civilian militia loyal to Barghouti that took a high-profile role in the second intifada, was designed with that end in mind. It stood apart from Arafat’s security services that were known for their brutality and corruption. It gave Barghouti his own power base, making it difficult for Arafat and the returnees to ignore him.

Also unlike the returnees, Barghouti took a visible early role in the second intifada, confronting the army by leading mass marches to the checkpoints, the infrastructure of imprisonment Israel had established during the supposed peace-making of Oslo. His fiery speeches, like his later Washington Post commentary, provided the rationale for a militarized uprising against the occupation.

However, Barghouti soon found events taking on a logic of their own. Palestinian civilians died in ever larger numbers as Israel crushed the resistance with overwhelming military might. In the face of Israel’s arm’s-length aggression – the F-16s and helicopter gunships Barghouti mentioned in his opinion article – Fatah fighters scored few military victories. Some units became either reckless or indifferent to civilian casualties on the Israeli side. According to the Israeli media, during his Shin Bet interrogations, Barghouti admitted “things lurched out of control.” Aware too that Hamas’ suicide attacks on buses and pizza parlors were getting more attention than failed operations against heavily armed checkpoints, elements within Fatah started to dispatch their own human bombs.

Israel grabbed Barghouti in spring 2002 as this turmoil was playing out among Fatah activists. Barghouti was accused of founding the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades, a claim he has denied, and directing its attacks on civilians and soldiers. The trial ended in the summer of 2004, with Barghouti convicted of ordering three attacks that killed four Israelis and a Greek Orthodox priest, and of a failed car bombing in Jerusalem. Less often remembered is that the Israeli court acquitted him of 33 other charges listed by the prosecution. The judges argued that the evidence showed these attacks were carried out by the Brigades, but not that he had personally directed them. Barghouti was given five life sentences, plus 40 years for the car bombing attempt.

Barghouti refused to cooperate with the court from the outset, saying it was a political trial, and he offered no legal defense. He maintained only that, while he supported armed resistance, he repudiated attacks on civilians. As the verdict was handed down, he called out to the judges: “I’m no more involved in these attacks than you are.”

Israeli officials have exploited Barghouti’s conviction to decry suggestions that he could ever be a partner for negotiations. It is impossible for Israel to deal with someone who has “blood on his hands,” they say. Gush Shalom, a peace movement in Israel, has noted how blind such assessments are to Israel’s own past. If the principle of holding Barghouti personally responsible for the actions of members of his organisation was to be extended to the Israeli leadership, several would have found themselves serving very long sentences. For example, Israel’s prime minister in the late 1970s, Menachem Begin, led the Irgun in 1946 when it blew up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people. Under the rules that applied in Barghouti’s trial, observed Gush Shalom, Begin should have been sentenced to 91 consecutive life sentences for that single attack alone.

The battle with Abbas

Barghouti’s credibility among Palestinians and outsiders grew not only because jail removed him from the increasingly tarnished world of Fatah politics. His work upholding the rights of Palestinian political prisoners has earned him much credit among the wider Palestinian public on an issue that most care deeply about.

And his continuing commitment to a peaceful solution to the conflict, as well as his criticisms of Palestinian corruption, have won wide approval. Last year Palestinian officials and human rights groups launched a campaign to have him nominated for the Nobel peace prize, a move that most notably won backing from the Belgian parliament. A sympathetic Palestinian documentary, titled simply “Marwan,” premiered in the West Bank early this year, with distribution planned across the Arab world.

Barghouti has become the chief challenger to Abbas’ visionless and increasingly autocratic rule. Back in 2004 he threatened to stand against Abbas following Arafat’s death, only relenting after he was dissuaded by his wife, Fadwa, and close friends – a decision he is reported to have come to bitterly regret. Following a series of threats by Abbas to retire, Barghouti has gone public with his intention to stand for election when Abbas departs.

Surveys of Palestinian public opinion indicate that Barghouti is well ahead of his rivals. Last year surveys showed he was twice as popular as Abbas, and outpolled Ismail Haniyeh, Hamas’ most respected politician. He has won allies in unlikely places in Fatah. Mohammed Dahlan, an ambitious arch-opponent of Abbas who was forced into exile in 2011, has said he will drop out of the succession battle if Barghouti contests it. Saeb Erekat, a long-time Fatah apparatchik who is closely identified with Abbas, has also backed Barghouti. Both seem to have recognized that the popular mood is with the imprisoned Fatah leader.

The contrast between Barghouti’s and Abbas’ philosophies could not be starker on the key issues: reconciliation with Hamas, security coordination with Israel, and support for grassroots activism, including non-violent protest and boycotts. Those differences were on display when Abbas met U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House in early May. Trump might have given Abbas’ campaign for statehood a small fillip by stating of a peace deal: “We will get it done.” But only if one believes Trump is serious in his extravagant claims. He also lavishly praised the Palestinian security forces’ cooperation with the Israeli army, saying: “They work together beautifully.” Sami Abu Zuhri, a Hamas leader, decoded that statement, tweeting that Trump had confirmed that the PA effectively received economic aid in exchange for crushing Palestinian opponents like Hamas.

At the same time as Trump is pruning foreign aid to many countries, Washington has announced that assistance will be increased to the Palestinian Authority. Palestinian analyst Ramzy Baroud pointed out that the money was little more than a bribe, rewarding the PA for “en-suring Israel’s security and … preserving the status quo.”

Abbas doubtless hoped that a meeting so early in Trump’s presidency would bolster him against critics and potential challengers like Barghouti. But the very fact that Abbas could travel to Washington and be feted by the Trump administration while Barghouti was in solitary confinement refusing food is unlikely to have made a good impression on many Palestinians.

Barghouti has reportedly told a confidant: “The [Palestinian Authority] can proceed in one of two directions today: to serve as an instrument of liberation from the occupation, or to be an instrument that validates the occupation. My task is to restore the PA to its role as an instrument of national liberation.”

Fearful for his own political survival, Abbas is reported to have conspired in keeping Barghouti in jail. He has not put pressure on Israel to release Barghouti as part of prisoner exchanges. Jamal Zahalka, a Palestinian member of the Israeli parliament, has said: “There were years when they didn’t want to hear his name in the Muqata” – Abbas’ headquarters in Ramallah.

The Palestinian president, it appears, is still plotting to deny Barghouti influence, even as speculation increases about how much longer the 82-year-old president can continue to rule. Last Nov. Fatah held a much-delayed congress at which it was hoped Abbas would share with potential successors some of the responsibilities of his three official posts – chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, president of the Palestinian Authority and chairman of the Fatah movement. He declined to do so.

But more significantly, Barghouti and his many supporters have been sidelined in the wake of the congress. The imprisoned Fatah leader received an overwhelming majority of votes at the congress – 930 of the 1,400 delegates – for a place in the movement’s central committee. But Abbas forced out of the running most of Barghouti’s potential allies who had intended to stand for election. At the central committee’s meeting in February this year, members ignored the wishes of congress delegates and selected a relative unknown, Mahmoud al-Aloul, a former governor of Nablus, as Abbas’ number two. Jibril Rajoub, a former West Bank security chief and the current head of Palestinian Football Association, was appointed the committee’s secretary-general.

On Facebook, Barghouti’s wife, Fadwa, accused the committee of giving every appearance of yielding to pressure from Netanyahu. In December the Israeli prime minister had condemned Barghouti’s election to Fatah’s central committee, saying it “radicalizes the culture of incitement and terrorism.” The decision to overlook Barghouti was also roundly criticized by Fatah cadres, former prisoners and members of the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades.

A poisoned chalice?

The question of Abbas’ heir is increasingly hard to ignore. The Palestinian president is said to be in poor health and his popularity likely only to sink further. One way or another, his days are numbered. Can a jailed Barghouti succeed him? Would Palestinians vote for a leader who cannot lead? A senior Fatah official has observed: “Perhaps his election will ultimately symbolize the Palestinian condition – a people under occupation with a president behind bars.” That symbolism would certainly be discomfiting for Israel. It would add to the pressure from Europe and the U.S. to free him.

Should it happen, what would his own long walk to freedom look like? Certainly, not much like Mandela’s. The South African leader was released as the apartheid regime was collapsing. He soon became president of a “rainbow nation” that embraced all South Africans, rather than the supreme leader of the Bantustans. Israel, on the other hand, would be installing Barghouti in a deeply compromised vehicle for self-government, the Palestinian Authority, still operating under occupation. His rule would extend only to the archipelagos of nominal Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank, surrounded by settlements and military bases.

Barghouti would find he had been handed a poisoned chalice – one that defeated both Abbas and, before him, Arafat. As the Israeli reporter Amira Hass recently observed, the Palestinian Authority “is a project that the world supports for the sake of regional stability. And ‘stability’ has become a synonym for the continuation of Israel’s settlements in the West Bank without any serious diplomatic or military implications for Israel.”

Barghouti believes the PA can be reformed. But how credible is his view? Can the PA lead, or even condone, a chaotic national liberation struggle – a grassroots movement supporting non-violent resistance and civil disobedience – when its institutional structures are designed to stabilize and regulate the occupation? Tens of thousands of Palestinian families rely on the PA for salaries and allowances. Its security forces are there to keep order alongside, and in cooperation with, the Israeli army. How can Barghouti be Palestine’s Mahatma Gandhi when the institutional role of the PA’s president is more like that of Marshal Philippe Petain, head of France’s Vichy regime under Nazi occupation?

If the PA cannot be reformed, it would have to be overthrown before Palestinians could stand any chance of liberating themselves. That core contradiction would be a difficult one for a President Barghouti to resolve.

He would likely face a further difficulty. Reports of the audience reaction to the early screenings of the documentary Marwan were revealing. Its producer, Raed Othman, observed: “While the film was being screened, we noticed that many of the young people attending who have known Marwan as a symbol were excited when they heard excerpts of some of his fiery speeches, but were not thrilled to see him defend peace with Israel.” Barghouti’s wife, Fadwa, has expressed the problem in a different way: “My and Marwan’s generation still harbors a spark of a hope that the conflict will end with a two-state solution. My children don’t believe in that; they aspire to a single, democratic state.” Indeed, many young activists have come to view the two-state solution as an illusion, one that derailed the national struggle for more than two decades. They are increasingly interested in a one-state solution, harking back to the original aims of the Palestinian Liberation Organization under Arafat.

Barghouti has proved repeatedly that he is ready to rethink strategy and to respond creatively to changing circumstances. That is a cause for hope. Can he rise to a challenge that would have proved daunting even for the real Nelson Mandela?

Update: On May 26, the hunger strike ended. Israel maintained that it had not negotiated with the prisoners. That, however, that was widely denied by those close to the prisoners. They said Israel had spent 20 hours in intense talks with the strike’s leader, including Barghouti, to bring the hunger strike to a quick end.

Israeli authorities confirmed that they had conceded one of the prisoners’ main demands – that two family visits be allowed a month. However, the prison service emphasised that the extra visit would be funded by the PA and organized by the Red Cross.

The PA reported other concessions: prisoners will be allowed to meet their children without a glass partition; night-time searches will cease; medical treatment is to be improved; all women prisoners will be placed in a single prison and only female guards allowed to search them; daily exercise times are to be extended; and all the prisons will have a kitchen area. A prison official denied the PA’s claims, saying it had not agreed to such “perks”.

In addition, reports suggest that the prisoners will be allowed – some time later, when Israel can plausibly deny a connection to the strike – greater access to academic studies and the media. Whether Israel has made any concession on the other main demand – placing payphones in prison wings – remained unclear at the time of writing, at the end of May.

A less obvious victory claimed by the prisoners is that the Israeli authorities were forced for the first time to recognise them as a collective party. The media reported that, despite Israeli denials, the Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence service, did negotiate with the strike leaders. A prisoners’ committee has reportedly been established under Karim Younes, a Fatah leader, that will oversee continuing negotiations. Implicitly, Israel has recognized both the status of Barghouti and other prison leaders and that it must talk to them to avert a renewal of the strike.

The Israeli authorities had worked hard to undermine the strike and discredit Barghouti personally. On May 7, the prison service released video footage, filmed inside a prison cell, of a man it claimed was Barghouti twice eating snacks. The Israeli media reported that the prison service had covertly smuggled the bar to Barghouti to damage his image. Amos Harel in Haaretz observed that the stunt had largely backfired: “It only strengthened his image as a leader who is feared by Israel – which resorts to ugly tricks in order to trip him up.”