| Also in this issue: In Memory Of W. Gary Melin |

By Steven Jungkeit

The Wheels Get Rolling

In his literary study “Beginnings,” the late Edward Said cautions against trusting origin stories. He casts doubt on the possibility of achieving a beginning, for any beginning, whether that of a novel or an idea, is always a fictitious proposition. We never begin, really, but only continue, following a story that is already underway. Every story, every idea, every institution, is merely a continuation of what already exists. And yet stories do begin. Journeys are set in motion, even if it is impossible to affix a clear origin of that story, of that journey.

So it is with the Wheels of Justice, a journey that took nearly thirty people through the American South this past October. It’s a journey that began in Old Lyme, Connecticut, one that passed through 12 states, while covering over 3,000 miles. It’s a journey that ended ten days later.

But endings too are to be distrusted, for the aftermath of all we experienced continues to unfold for all of us who participated in it.

But back to the beginning, or at least, the beginning I wish to fasten upon. In a very real sense, the Wheels of Justice journey began in Palestine. I’m a minister at the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, and one of the things I’m privileged to do is to lead groups to Palestine in order to witness the human rights abuses occurring in that part of the world, as well as the political, cultural, and spiritual resistance that takes place among people of conscience in that part of the world.

Our journeys operate under the aegis of the Tree of Life, an outgrowth of our community in Old Lyme, though the roots of that tree have now spread to other communities throughout the United States. That image, the Tree of Life, is drawn from the final pages of the New Testament, where the poet, John the Revelator, imagines a tree planted by a river, one whose leaves shall be for the healing of the nations.

As I imagine it, that image is an invitation to readers of any and all persuasions to take up that healing work for themselves, as if to say, at the close of that famous book: “This is your work, to tend the tree, and to prevent its roots from being choked by the perennial issues that plague humanity – violence and warfare, hatred and fear, suspicion and theft, cultural erasure and political domination.”

In the West Bank, we often stay at a hotel a block away from the Separation Wall, and I’ve made it a habit to spend a little time studying the graffiti along the wall each time I visit. The images and text change from month to month and from year to year, and I find that it’s a helpful way to document the current of the times. This past January, one of the panels had the slogan “From Ferguson to Palestine” scrawled upon it. It was faded, and several other messages had been written on top of it. It wasn’t a new phrase or insight, but seeing it written upon that wall brought the visceral truth of that phrase home in a new and dramatic way. And it seemed clear that it was time for those of us who care about what’s happening in Palestine to start connecting how the human rights abuses in the Middle East are linked to the abuses that occurred, and are occurring, in the United States.

There are many reasons that the United States continues its ongoing support for the Israeli occupation, but one of the most powerful is surely that to confront what’s happening in Palestine means that we’re required to confront our own history of settler colonialism, our own history of racial subjugation, our own history of genocide and ethnic cleansing, our own history of deriving privilege from the suffering of others.

Standing before that Wall this past January, it seemed all too clear that to claim an allegiance or affinity to Palestine required an equal commitment to dismantling the structures of abuse and privilege that exist here in the United States.

Upon returning, a handful of people within the Tree of Life and the First Congregational Church began to share conversations about what it would mean to connect things up. Eventually, we mapped out a journey that would lead us through Washington, D.C., Charleston, Americus, GA, Atlanta, Montgomery, Selma, Muscle Shoals, Memphis, Cherokee, NC, and Baltimore.

As we talked and planned, we became increasingly convinced that as various struggles for human and civil rights have erupted across the globe in the past several years, each of those struggles was inextricably linked by common challenges and by shared tactics of resistance.

Specifically, we wished to address several contemporary instances of colonial aftershocks: Palestinians struggling to maintain dignity in the face of ethnic cleansing and a military occupation; people of color in the United States facing mass incarceration and police brutality; and Native Americans preserving their traditions in the face of generational trauma and social invisibility.

But we also wished to interrogate the ways those in positions of privilege suffer the consequences of colonialism in their own lives, where conditions of material abundance yield an equal but opposite condition of cultural, spiritual, and moral deprivation.

Our intention was to confront the many dimensions of living in a time when lands, lives, minds, and futures are determined by the logic of occupation, racism, and cultural erasure, all stemming from the violent legacy of colonial control. We wished to design a journey for those who believe that another world is possible, for those who wished to have their spirits and consciences quickened, for those with religion and without it, for those who wanted to see and understand the connections between struggles in two very different parts of the globe.

In the months after that visit to Palestine, we drank countless cups of coffee, all the while sketching an itinerary for those who desired to listen, to witness, and to act against the ongoing legacy of colonialism and its varied aftershocks.

And so on a chilly October morning, the Wheels of Justice travelers boarded three vans, and made our way south. Many of us came from Connecticut, while some came from Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, and Tennessee. One among us was a member of the Lakota tribe, and had recently arrived from the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota.

We stayed in budget motels, checking in late and checking out early. We ate on the run, on roadsides, in parking lots, and sometimes, when we were lucky, in fabulous barbecue shops, hot chicken shacks, and legendary soul food joints.

We were moved to tears by what we encountered, and sobered by the struggles that still exist in this country. We came away chastened and horrified by some of the things we witnessed. For a time, it was difficult to speak about the journey, or to write about it.

But we also came away powerfully affected by the people we met, by the stories we heard, by the history that was opened to us. We came away inspired by the courage, tenacity, and creativity of so many whom we encountered along the way, which functioned as an antidote to the sense of despair that might otherwise have set in on such a journey.

What I’d like to do in the coming pages is to describe some of what our Wheels of Justice participants experienced. My account won’t be comprehensive. It won’t provide an exacting description of the journey. It will, however, dwell on several crucial moments along the way, moments that draw Palestine, the Black Freedom Movement, and Native American struggles into sharper relief. Charleston shall be our first destination.

Charleston: A Tale of Two Cities

In truth, it’s two cities I have in mind, not one. And it’s two scenes I’d like to recount, separated in time and space, but joined by a common ideological thread.

One scene unfolds in Charleston. The other rises out of Hebron, one of the most bitter and contested zones in the occupied territories of Palestine. Both cities, and both scenes, are well known and heavily documented, but they are rarely understood as connected, one to the other. For all their external differences, I would propose Charleston and Hebron as sister cities, joined by the traumatic aftershocks of settler colonialism, but also joined by a tenacity of spirit that somehow, in some way, manages to shine through all that pain.

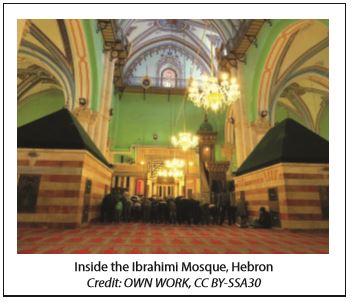

The first scene took place on June 17, 2015, in the city of Charleston. On that steamy summer evening, a young man named Dylann Roof entered Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in downtown Charleston and attended a Bible study.

Mother Emanuel is one of the oldest and most historic black congregations in the United States, dating back to the early years of the 19th century. Dylann Roof was welcomed into the community that night, and he sat for nearly an hour as participants at the Bible study shared their insights. When the minister, Rev. Clementa Pinckney called for prayer, those gathered bowed their heads. It was then that Roof stood up and opened fire, killing 9 members of Mother Emanuel.

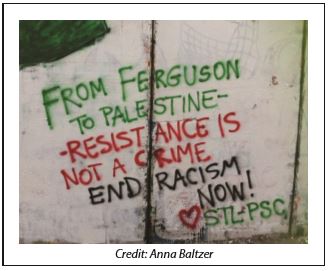

The second scene took place on February 25, 1994 in the city of Hebron, some twenty miles south of Jerusalem. Hebron is the largest city in the West Bank, and one of the most fiercely controlled by the Israeli military in all of the occupied territories. That status has to do with the presence of the tombs of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the center of the city, a fact that renders the city immensely desirable to Israeli settlers.

On that day in 1994, an Israeli physician named Baruch Goldstein walked into the Ibrahimi Mosque, a place of Muslim worship immediately adjacent to a synagogue, which shares the site. It was Ramadan, and nearly 800 Muslim worshipers had gathered to pray alongside the tombs of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Goldstein was dressed in military fatigues that allowed him to pass as an IDF soldier. He entered the mosque and waited until the moment that worshipers knelt, their heads prostrate on the floor. He then opened fire, killing 29 people and injuring 125 others.

The Charleston and Hebron incidents are separated by two decades, by thousands of miles, and by very different cultural settings. Yet they both testify to the brutal legacy of settler colonialism being played out in different parts of the globe.

Goldstein wished to “purify” Israel of its Arab population, arguing as far back as 1981 in The New York Times that in order to achieve security and stability, Israel must work to remove any Arabs from within its borders.

Emigrating to Israel from Brooklyn only intensified Goldstein’s hatred, leading to a series of incidents that culminated in his attack. From refusing to treat patients of Palestinian descent in the emergency room in which he worked, to defacing the property of the Ibrahimi Mosque prior to the shooting, Goldstein signaled his antipathy to Palestinians for years prior to that fateful day in 1994.

Tellingly, in the aftermath of the massacre, Israeli settlers in Hebron constructed a shrine to Goldstein’s violence, a place for pilgrims to venerate Goldstein’s act. Though the shrine has now been removed, Goldstein’s grave is still prominently located in Kiryat Arba, the settlement on the outskirts of Hebron in which he lived and worked. When I visited the site in 2015, I saw stones resting upon the flat face of the grave, a sign of honor and respect. It’s one of the ugliest things I’ve ever seen.

Dylann Roof was also animated by notions of racial and national purity. He wished to reassert the dominance of the white race, appearing in photos alongside the colonial flag of Rhodesia, a symbol of white dominance over an African population. In the lead up to the murders, he studied sites around South Carolina important to African Americans, and he knew well the symbolic significance of Mother Emanuel as a site of black freedom.

No shrine will ever be constructed for Dylann Roof, but it’s notable that his actions took place in a city where numerous Southern Confederates are enshrined. Not only that, when family and friends of the victims at Mother Emanuel gathered in the immediate aftermath of the shootings, they were taken to the Embassy Inn and Suites Hotel just down the street, located in an historic building first used by the Citadel, South Carolina’s revered military academy. The Citadel was founded in 1842 to reassure a skittish white population that they would be protected by a military presence if a slave uprising occurred in the city. Ironically, the triage center used on June 17th testified to an earlier racial history that has still not been resolved. The hotel, like the shooting itself, is an aftershock of settler colonialism.

The Wheels of Justice travelers converged on Charleston on the second day of our journey. Some of us had been to Hebron, and had seen the scars that still lay upon that city. But that night in Charleston, it was that terrible June night a little more than a year earlier that was on our minds.

Some of us listened to a short talk about the history of Mother Emanuel shortly after we arrived, and our guide shook his head when the subject of Palestine came up. “I don’t think that problem will ever be solved,” he sighed. “Same thing with race in America,” he continued. “I don’t think we’ll ever get to the bottom of that. It’s the same in both cases, America and Palestine. We know that sooner or later, some kind of hate and violence is going to rain down, as sure as we know the rain’s going to fall here in Charleston. The best we can do is to make a kind of umbrella that can give us a little shelter when it does rain down. That’s what this church is. That’s what it has been. Though sometimes the rain falls hardest on us.”

Not long after that conversation, we sat in the very fellowship hall where that Bible study had taken place in June 2015, and where all that hateful rain had fallen upon the Emanuel 9. Though we were all acutely aware of our surroundings and what had occurred there, we shared a delicious meal with members of the Mother Emanuel congregation. The conversations between us were tentative at first, and there was no mistaking that we were in a space marked by profound pain.

But there was also a sense of warmth and joy in that room, even amidst the pain. At the end of the evening, the choir from Mother Emanuel stood up and sang an old gospel hymn that left everyone in the room uplifted and inspired. It was called “My Hope is Built on Nothing Less.” The refrain goes: “On Christ the solid rock I stand, all other ground is sinking sand, all other ground is sinking sand.”

Those words use the ancient language of religion to upbuild and uphold the dignity and worth of black humanity in a country, and in a city, that has vacillated between indifference and open hostility for centuries. It was a way of claiming and reclaiming a space that had been desecrated by the aftershocks of settler colonialism.

As we sang along, my thoughts drifted to the times I’ve been fortunate enough to visit the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron with Muslim friends. They face in the direction of Mecca, and place their foreheads against the ground in a gesture of humility and devotion. Witnessing their prayers is to witness a claiming and reclaiming of life. It is to witness a sacred space being reclaimed as sacred, after undergoing unspeakable trauma.

In both settings, those acts of prayer function as profound acts of resistance to the aftershocks of settler colonialism.

Global Pacification in Atlanta

On the fourth day of our journey, we were privileged to visit Emory University, and to hear from Elizabeth Corrie, a professor of youth education, who also works on issues related to Palestine.

Beth is the cousin of Rachel Corrie, who was murdered in 2003 when she stood her ground before a bulldozer destroying a Palestinian home. Rachel’s death was a catalyst for Beth, and she began immersing herself in the Palestinian struggle. These days, Beth also runs a summer program in Atlanta called the Youth Theological Initiative, an innovative and interdisciplinary seminar that helps high school students attend to the best and most prophetic insights within the various traditions they might belong to. She was exactly the person to connect the threads that needed to be connected between Palestine and the United States.

Beth began her presentation by screening a video entitled “When I See Them, I See Us.” It makes a powerful visual connection between the Black Lives Matter movement and the struggle against the occupation in Palestine. Shots of armored police in Ferguson are interspersed with images of armored IDF soldiers in the West Bank, of protesters along the Separation Wall in Bethlehem, and of young people in various American cities protesting their own seclusions and vulnerabilities.

Beth went on to observe that connections between Palestine and the Black Freedom Movement aren’t new. She noted that SNCC, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, had made that connection in 1967 in one of their newsletters. She noted that while Martin Luther King openly endorsed Israel, identifying Zionists as the oppressed, Malcolm X drew connections between black life in America and Palestine, going so far as to visit Gaza at one point.

She read us poems written by black Americans and Palestinians in the 1980s and 1990s, as those communities recognized their common struggles. And she noted the ways those commonalities became all too apparent recently.

No doubt there are powerful differences, and no doubt the struggle in Palestine is not identical to the struggles occurring throughout the United States right now. No doubt. But the similarities are too overwhelming to ignore.

So what are the ways these issues are connected? How do our own domestic practices mirror what we see going on in Palestine?

Start with land. We know well that the same process of land expropriation and ethnic cleansing used against Palestinians was used here in the United States against Native Americans. That’s one of the reasons U.S. citizens cite when trying to dismiss the claims of Palestinians — it needed to happen in order to get where we are, and well, who can argue with the march of progress?

But closer to the present, we also know that Palestinian protesters tweeted advice to protesters in Ferguson when tear gas was sprayed, sharing with young people in a St. Louis suburb some of the hard-earned wisdom that comes with life under occupation. Similarly, after the tear gas was fired, protesters in both locations compared notes, and discovered that the same tear gas used in the West Bank was being used in Ferguson. A U.S. company called Combined Systems, Inc., located in Pennsylvania, manufactures that gas. Empty shells were also discovered in Cairo, Egypt, after police clashed with protesters in Tahrir Square.

But the connections continue. It’s been well documented that U.S. police forces have steadily been militarized for the past 30 years in response to the War on Drugs,, so that it’s easy to mistake images from Charlotte or Baton Rouge for images from the West Bank.

We know that police all across our country routinely receive training in Israel on ways to pacify street protesters, and we also know that police brutality is as endemic here in the United States as it is in Israel, with particular force being reserved for children and teenagers, who are routinely incarcerated and yes, tortured.

We know that mass incarceration has been a strategy employed in both countries to eliminate resistance, and we know that security companies like G4S have made enormous profits in Israel and the United States alike. In fact, G4S has been employed by allies of the Dakota Access Pipeline project to intimidate the water protectors at Standing Rock, a scene that now also resembles the militarized zones of our urban centers, and of the West Bank.

And we know that all of this thrives under a regime of structural racism, which legitimates and fuels the separations and tensions, the violence and divisions, all the more.

The connections are real. As important as the realization that the issues are connected, however, is the question of why they’re connected. Here, Jeff Halper’s work on global pacification systems is extremely relevant. In his recent book “War Against the People, “ Halper argues that the connections people like Beth Corrie are rightly discerning between Palestine, the Black Freedom Movement, and the protests at Standing Rock have to do with strategies of containment on the part of a global elite, concerned about maintaining a particular financial system upon dispersed but interconnected peoples whose lives have been rendered precarious. Under that regime, various populations have become extraneous to the smooth functioning of powerful political economies, whether from the collapse of industrial labor or from the effects of settler land grabs.

Tellingly, Palestinians, Native Americans, and African Americans have all been subject to that dynamic as large swaths of different populations in different locales and in different historical eras have been prevented from participating in a mainstream economy, thus creating populations and geographies of political unrest. (That dynamic has now caught up with working class white folks as well, a dynamic that was exploited to great effect in the election rhetoric of Donald Trump.)

Typically, the solution to potential unrest has been containment, using a strict spatial control: the reservation (supplemented by the prison), the ghetto (supplemented by the prison), or an occupied territory (supplemented by the prison or the detention center).

But when those populations grow ever more restive, as they must, more extreme measures are required. Halper traces the rise of an entire global industry meant to subdue and control populations that have become superfluous to the functioning of global capitalism, from surveillance technologies to the construction of detention centers, from weaponized police forces to tactical training in urban warfare and the intimidation of ordinary citizens. Halper argues that what we’re witnessing in the present isn’t so much the proletarianization of the world, but the Palestinianization of the globe, where Palestine functions as a laboratory for global pacification strategies. Those strategies are then treated as commodities on the world market, as other countries, from Brazil to China to India to the United States, prevent their own “extraneous” populations from achieving a full throated revolution.

The connection that Beth Corrie is making between Black Lives Matter and Palestine, coupled with Jeff Halper’s trenchant social analysis of global pacification systems, is alarming to confront.

But confront it we must. When I conclude services in my own congregation, I typically urge people to go out into the world in peace, having courage. That night in Atlanta, it wasn’t peace that I hoped our Wheels of Justice travelers would feel. And so I urged them to go into the world agitated, outraged, and shaken. I urged them to go into the world not filled with peace, but upset, troubled, broken hearted, and impassioned. It was late by the time we departed Emory, but I didn’t wish our travelers an untroubled night of sleep. I wished them a night that was restless and disturbed. I wished them minds unquieted by all we had learned.

Commerce Street

The following day found us in Montgomery, Alabama. We rolled off Interstate 65 and headed toward downtown, close to the state capitol building where Martin Luther King had spoken following the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March, close to the place that Rosa Parks had boarded the bus a decade earlier, refusing to yield her seat, all within the city in which the civil rights movement had achieved its first public victory.

But it wasn’t any of the city’s historical locations that drew us. We were interested in visiting the Equal Justice Initiative, a legal defense firm founded by Bryan Stevenson, author of the book Just Mercy. EJI is located in the center of Montgomery, on Commerce Street, so named because of the commercial enterprise that once dominated Montgomery’s civic life: the slave trade. A marker just outside of the EJI offices tells how in the 18th and 19th centuries, human captives were taken off boats on the Alabama River and marched through the center of town, on Commerce Street, to be sold at auction. Stevenson and his team of lawyers have planted similar markers throughout Montgomery, with more to come, as a way of helping the community, and the country, grapple with the traumatic legacy of the slave trade. Stevenson’s thesis is that until we actually confront that violent history, we’ll never be enabled to create the just and humane present that many people actually desire.

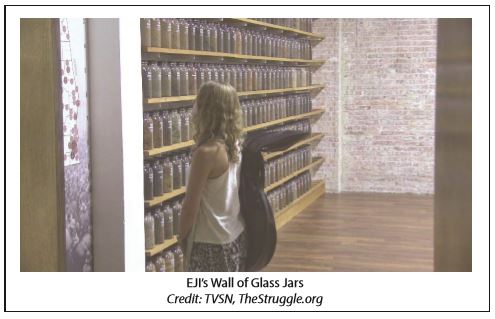

In addition to the historical markers that EJI is placing around the city, the organization has also started a large public display dedicated to confronting the history of lynching in the South. Over 4000 men, women, and children were lynched under a regime of racial terror in the 19th and 20th centuries, and prior to EJI’s work, no detailed public recognition of those events had taken place. And so, after walking through a corridor of offices, we were invited into a large lecture hall, the back wall of which was given over to shelves of glass jars, each containing soil of various colors and hues, each containing a name. The soil had been collected from sites around the state of Alabama where lynchings were known to have taken place. Through painstaking research, EJI identified the names of those who had died, and matched the names with locations. Following that, teams of people had visited each location, bringing back earth from each site, placing it in one of the jars, where it is now displayed within EJI’s offices. It’s hard to convey how visceral that display is. It’s hard to convey the sorrow that arises as one stands surveying all those names, imagining all the terror and pain that each of those jars somehow contained.

Still harder to convey is what happened next. EJI’s primary mission is to offer legal defense to those who have been wrongfully or unfairly sentenced to death or life in prison. That work is born from the conviction that America’s legacy of racial terror didn’t cease with the civil rights era, and isn’t limited to isolated outbursts such as the shooting that occurred in Charleston. It now occurs through the prison industrial complex and mass incarceration, where human lives that have been deemed to be extraneous to global capital are warehoused, and then abandoned. Indeed, the rise of the prison industrial complex is a significant piece of the global pacification strategy that Jeff Halper details in his work, as neoliberal governments seek to contain populations deemed extraneous to the smooth function of economic processes. Since the mid-1970s in America, prisons have been used to warehouse predominantly black and brown bodies, though in many locales, that industry has now caught up with white populations as well. Nevertheless, the fact remains that people of color are most vulnerable to that system, falling prey to it at an alarming rate. EJI works to address those injustices by taking on legal cases of those who received inadequate representation in earlier trials.

After witnessing the soil project that documents lynchings, we were shown a news clip about a man named Anthony Ray Hinton. Hinton had been wrongfully accused of murder in 1985. Despite overwhelming evidence that would have exonerated him had he been given adequate legal assistance, he was sentenced to death. As a result of EJI’s involvement, Mr. Hinton’s case was appealed all the way up to the Supreme Court, which overturned his sentence after 30 years. It was a moving story. What shocked us was that when the news clip ended, Mr. Hinton himself walked into the room. For the next hour, he shared his story in full.

He described how, on the day of his arrest, he had been out cutting the grass at the house he shared with his mother. He described how, after his arrest, he assumed the matter would be cleared up with a few easy phone calls that would establish that he was nowhere near the crime scene on the night of the murder. He described how, when he attempted to explain himself, the sheriff responded that he simply didn’t care. In careful and measured tones, Mr. Hinton recounted how the sheriff told him that it didn’t matter whether he committed the crime or not. An all white jury and a white judge will insure that you receive the death sentence, the sheriff told Mr. Hinton. Indeed, the sheriff’s words came to pass. Beginning in 1985, Mr. Hinton took up residence in a 7×5 foot cell, spending the better part of thirty years in solitude. Mr. Hinton described how he devised methods to preserve his sanity, letting his imagination roam in flights of fancy in which he visited far flung locales, and met with notable individuals who reminded him of his own dignity and worth. When he spoke, his eyes were fixed not upon us, really, but upon what seemed to be a fathomless abyss that opened as he recounted the details of his ordeal. He broke down in tears often.

Two details linger. The first is that his confinement hasn’t ended, not really. Mr. Hinton shared that one of the first things he did upon being released was to buy a king sized bed to stretch out in. He thought it would feel magnificent. What he discovered was that his body was so accustomed to sleeping in the fetal position, his knees pulled up close to his chest (as necessitated by the measurements of his cell), that he still slept that way, as if confined. So too, he shared that upon his release, he dreamed of being able to shower for as long as he wished and whenever he wished. Sadly, the bodily discipline exerted upon him in prison carried forth into his freedom, so that he only feels comfortable showering every other day, and for a brief instant. In ways large and small, Mr. Hinton’s confinement continues, despite the relief of his release.

The second detail is this. He emphasized that though the state had taken away his freedom, though the state had robbed him of 30 years of his life, he said that they could never take away his joy. It was a paradoxical statement, for he uttered those words as tears flowed down his face. Joy, for Mr. Hinton, is clearly a quality different from happiness, one that is quite compatible with sorrow. It is also compatible with forgiveness. Mr. Hinton stressed that in order to preserve the best parts of his humanity, it was necessary for him to forgive those who subjected him to his ordeal. He did so not to eliminate the need for justice, but to insure that his own soul wasn’t degraded and diminished by what had been done to him.

In Palestine, I learned a word from a literary scholar living in Bethlehem, a wise and learned man named Qustandi Shomali. He spoke about the “pessioptimism” of the Palestinian people, who are acquainted with the worst that can befall human lives, while also maintaining a steadfast commitment to living lives filled with dignity, justice, compassion, and hope. From within the very space of tragedy, Palestinians have, by and large, managed to resist the daily humiliations of occupation by preserving that within themselves that is capable of generosity and celebration, hospitality and laughter, forgiveness and yes, joy. In Palestine, as in Montgomery, there exists a joy that no military occupation or racist criminal justice system can ever destroy.

If it ever came to pass that Mr. Hinton was able to visit Palestine and to share his story, I believe that many in Palestine would instinctively recognize the absurdity to which Mr. Hinton was subjected. And if those in Palestine could share their stories with Mr. Hinton, I have a hunch he would instinctively recognize the pessioptimism that so characterizes the people I have encountered throughout the West Bank. I tend to believe that they would understand one another as companions, separated by geography, but joined by a common oppressor, and by common strategies of soulful resistance. Commerce Street, it turns out, is a road that leads to the Occupied Territories.

Flash of the Spirit

One of the travelers on the Wheels of Justice journey was a man named Travis Harden, a member of the Lakota Native American tribe, and lately, a resident at the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline. I’ve been privileged to spend time with Travis in Palestine and in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Travis participated in the American Indian Movement (AIM) back in the 1970’s, and is a nephew of Russell Means, one of the leaders of that movement. And so Travis has a powerful appreciation for the ways the United States and Israel are linked not only by racism, but by the history of settler colonialism, where native and indigenous populations are displaced in order to make room for a dominant settler population.

These days, Travis makes a living through his art, selling paintings and other crafts that he makes. But he’s also a gifted musician, teaching Lakota songs to young people especially, but really to anyone willing to learn. That’s a large part of what he does at the Standing Rock Camp, but it was also a distinctive gift that he brought to the Wheels of Justice journey.

At Mother Emanuel, and at Koinonia Farm, at the annual meeting for the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights and at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, in Memphis beside the Mississippi River and in Cherokee, North Carolina, where one of the most egregious incidents of ethnic cleansing against an indigenous population took place, Travis shared his songs. He kept time with a small drum that he made, and his voice boomed across the traffic or the crowds that often surrounded him. In the oral tradition to which Travis belongs, songs become embodied memory, embodied liturgy, embodied prayer.

Travis’s presence was also a continual reminder that the aftershocks of settler colonialism aren’t limited to human populations alone. Indeed, one of the most significant aftershocks of settler colonialism has been damage done to the environment.

Those issues are dramatically displayed in Israel and Palestine, for every time we visit the Jordan River, or visit the Dead Sea, we confront the ways in which environmental resources are squandered in order to benefit a settler population. And as with the Dakota Access Pipeline project, as often as not, it’s indigenous or other minority populations that are exposed to the greatest hazards of settler colonialism. In North Dakota, the pipeline was originally deemed too dangerous to pass through the city of Bismarck, and so those hazards were removed to the Standing Rock Reservation. In Israel and Palestine, it’s Palestinian water sources that are most often fouled by run off or sewage from Israeli settlements. It’s clean drinking water that is often diverted from Palestinian rivers and wells in order to fill swimming pools within settlements, or to make the Negev bloom. Human populations suffer because of those decisions, but the natural world suffers as well. Travis’s songs were continual reminders of the ways settler colonialism and its aftershocks damage all manner of relationships, including that between humanity and the natural world.

Aliya Cycon was another of our Wheels of Justice travelers, a recent graduate of Berklee College of Music in Boston. As a result of a long stay in Palestine, living in places like Ramallah and Jenin, Aliya took up the oud, first as a hobby, then as a passionate student, and now as a vocation. Like Travis, Aliya understands the power of music to move mountains, and people as well. She understands that the oud is a way of calling forth the world of spirit, of providing soul within difficult or painful situations. Aliya learned her art, in part at least, from those who knew that preserving and protecting that which was best in themselves would come through an ancient form of music. Aliya drew upon that world when she performed for our group in Charleston on the morning after our visit with Mother Emanuel, and she did so in Atlanta, after we heard Beth Corrie’s trenchant analysis.

On the final night of our journey, Aliya and Travis joined together, and sang a song of lament. It was a song originally composed for Aliya’s grandmother, but in that moment, it widened to include a lament for all we had witnessed on our journey. It was a lament for those who were slain at Mother Emanuel, and those who were left behind to grapple with what had happened. It was a lament for all of those in Palestine who suffer under a military occupation. It was a lament for those at Standing Rock, standing to protect their land and their water. It was a lament for Mr. Hinton, and all he had suffered. It was a lament for those individuals, and for so many others. Travis and Aliya’s blended voices became a powerful symbol of the interconnections of the many struggles we confronted. But it became more than that to me. Their performance together became a symbol of the fusion of spirit and soul among the populations most powerfully affected by the aftershocks of settler colonialism. Their song was a flash of the spirit that signified the capacity to resist and revolt, and to create moments of beauty and grace even under immense pressure.

Where Do We Go From Here?

So what is to be done? Where do we go from here?

Those are the questions that were on our minds as we traveled, learning from the legacy of the civil rights movement, while also learning about the profound work that’s taking place throughout our country right now.

In Charleston, at Mother Emanuel church, we were reminded of the power of hospitality and forgiveness.

In Beaufort, SC, we were reminded of the power of sacred storytelling in order to keep the human spirit alive.

In Koinonia we were reminded of the power of community and shared life.

In Atlanta we were given reminders of the need for research, reading, and joining the connective threads across various struggles. We were reminded of the need to create an entirely new economic paradigm.

In Montgomery we were given lessons on the importance of memory, and the importance of activism. We were told by a man who spent 30 years in prison on a wrongful conviction that even though the authorities had taken his freedom, they could not take his joy.

In Muscle Shoals we learned about the marvelous power of song for uplifting the human spirit.

In Birmingham and Memphis, but really everywhere, we learned about the power of the written and spoken word, and we learned about the importance of feeding our bodies and souls with good food.

We didn’t do Cherokee the justice it deserved, but everywhere we went, Travis Harden reminded us of the Standing Rock protests, and the power of prayer when it comes to confronting past and present injustices.

And in Selma, in Selma, we heard from a minister named Leodis Strong who confessed to his own despair at times, but who told us that he still is listening to the voices that call to him from the Edmund Pettus Bridge, all those courageous people that put themselves on the line to make a better world for themselves and for their children. He told us that it hasn’t been easy in Selma, but that he remains committed to the work of caring for his people, committed to the work represented by that march in 1965, committed to preaching the good news in a city that, for all of its symbolic prestige, counts the local Wal-Mart as the only viable gathering place for people in town. Leodis Strong was but one voice. Even so, his was a reminder not only of the burdens of the work before us, but of the necessity of it as well.

Those of us who embarked upon the Wheels of Justice journey returned home in a state of exhaustion, but also acknowledging that something profound had occurred along the way. I was, I am, haunted by what we saw and heard. And I am certain that Edward Said was right all those year ago in his literary study, Beginnings. We don’t really begin at all. We join a story that’s already underway, in medias res. If that’s true, then it’s also true that stories, and journeys, can never really settle at a resting point. They continue to unfold, ignoring feeble temporal boundaries like beginnings, and endings.

The Wheels of Justice, then, shall continue to turn.