By Atef Abu Saif

There are two Gazas.

The first Gaza, as presented in the media, is a place of conflict and breaking news.

The second Gaza is a normal place where people pursue their lives despite all difficulties and challenges.

The second Gaza is more human and courageous and decisive than the first.

In the first Gaza, people are numbers, the statistical count following tremendous events of killing, destruction and massacres.

In the second Gaza, people are very normal. They love and hate. Some are heroes while others are cowards. They are not numbers, but tales full of life, dreams, moments of joy and moments of sadness.

In the second Gaza, there are writers who fight to have their books published – some might dream of becoming a Nobel Laureate.

In the second Gaza there is a girl who thinks she could be crowned Miss Universe if she competes.

In the second Gaza there are singers, dancers, actors and painters.

It is easy to talk about the first Gaza, while the other Gaza is rarely reported.

The aim of this article is to shed light on that second Gaza, the unreported one.

Gaza and the Middle East Conflict

Gaza has been one of the main stages for the Middle East conflict for the last seven decades.

Following the 1948 war, the southern coastal district of Palestine found itself the recipient of thousands of refugees and the center of a strong political movement. From 1948 until 1967, Gaza was administered by the Egyptian government. The Fidayeen, freedom fighters, started their struggle against Israel during this period and the Palestine Liberation Organization (P.L.O.) factions, including Fatah, formed from the Fidayeen in the early 1960s.

Due to this, it would be true to say that Gaza was the birthplace of contemporary Palestinian nationalism.

In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization was founded as a representative of the Palestinian people’s aspiration for freedom. and the first Palestinian council was held a month later. The majority of Fatah’s founding fathers came from Gaza. They include Yasser Arafat, Khaleel Al-Wazeer (military commander of Fateh), Salah Khalaf, Kamal Edwan, Mohamad Yousef Najar. Even the smaller leftist movement, the Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine (P.F.L.P.), while founded by Palestinians living in refugee camps outside Palestine, used Gaza as a stronghold of their military wing. Mohamd Assoud, known as Guevara of Gaza, led the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine guerrillas against the Israeli army in Gaza until he was assassinated in 1973.

In contemporary times, the emergence of political Islam came from Gaza. The two main Islamic movements, Hamas and Islamic Jehad, were founded in Gaza. Islamic Jehad’s founder Dr. Fathi Shikaki was from Rafah camp. Hamas founder Ahmad Yassen and all his cofounders were from Gaza.

Israel occupied Gaza in 1967 and the Strip has been a theater of continuous Israeli military operations ever since. Even after Israel’s so-called withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, Israel has imposed a military siege on the territory, and has never stopped its operations inside the highly populated territory.

Israel launched three massive assaults against Gaza in the last eight years. The first took place from Dec. 22, 2008 to Jan. 18, 2009 and killed 1,419 Palestinians, including 1,167 civilians, of whom 308 were under the age of 18. According to the Gaza-based Palestinian Center for Human Rights, 5,000 Palestinians were wounded, 3,540 housing units were completely destroyed, while 2,870 were partially damaged. 268 private businesses were destroyed and another 432 were damaged.

In Nov. 2012, Israel launched another assault against Gaza that lasted eight days. According to the Al-Mizan Center for Human Rights, 178 Palestinians were killed and 1,039 injured, 963 houses were totally destroyed and 179 partially damaged. The attacks destroyed 110 health centers, 35 schools, two universities, 15 N.G.O. offices, 30 mosques, 14 media offices, 29 industrial and commercial facilities, five banks, two youth clubs, three cemeteries, two bridges, 14 police/security stations and eight government ministry buildings.

The third assault took place from July 7 to August 26, 2014. According to Al Mizan, 2,217 Palestinians were killed, among them 550 children and 239 women. At least 10,918 people were injured, half of them women and children. Nearly 111,000 houses were damaged or destroyed. The attacks reduced to rubble 98 schools, 161 mosques, 8 hospitals — 6 of which are still out of service, 46 N.G.O. offices, 50 fishing boats, and 244 vehicles.

Drones over Gaza

When you live in Gaza, you cannot miss the continuous presence of drones in the sky. Drones are part of life. They are there because they are there, as if Gaza cannot exist without them.

Their whirring is the background soundtrack in the drama of life in Gaza. If you do not hear their sound, you will notice their presence while watching TV, when the drones interfere with satellite signals and you lose reception for a few minutes now and then. I used to joke with my friends that every person in Gaza has a drone watching him. If they are not there, we miss them and search for them in the sky.

Drones are not only military weapons that watch and kill. They are part and parcel of the tools Israel uses to remind the people of Gaza that Israel has not left, that there is an Israeli soldier somewhere behind a screen watching them. He might, if he wants to, hit a target just as a boy might do while playing videogames. Gaza, indeed, is the soldier’s favorite videogame. Whenever I hear the whirr of the drone I feel I am a target in a videogame.

Now, while not physically present, Israel follows every little detail in Gaza. Its ships are situated only a few miles off shore. Its tanks are within reach of the borderland and cross it now and then. Most importantly, its army is watching over Gaza through receiving and analyzing every minute image captured by the drones hovering in the skies of Gaza.

The Israelis use other remote-controlled machines, too, such as balloons and robots. While walking in the border towns and villages, north, east or south, you can easily see the balloons hanging in the sky spying on Gaza.

This is a new form of occupation. Instead of having soldiers among the Gazans, Israel is present inside their houses, classes, restaurants, analyzing the air they breathe. This is a digital occupation that is inexpensive for the occupying power and costly for the occupied. It turns the people in the occupied territory into objects in a digital machine. They are not only occupied and subject to the military machine and hegemony, they are transformed into digits in this process. The soldier kills and destroys mechanically. Instead of being the master of the machine, he is made into its slave. In this process both the soldier and the occupied people are dehumanized unwillingly.

Gaza is subject to a severe Israeli siege which restricts the movements of people to and from Gaza. Israel limits the ability of the fishermen to sail in the sea. The Gaza international airport was destroyed by the Israeli forces. In other words, Gaza is the largest prison in the world.

In this prison, the second Gaza lives joyfully despite the limits and restriction of the place. This second Gaza writes poems and fiction, paints, dances, sings and defies the limits in its own way.

Why Go to School?

Despite the economic hardships that Gazans face, education has always been a priority. More, not less, university programs are now available, the number of students has increased, and universities have opened new campuses.

According to statistics provided by Gaza’s Ministry of Higher Education, 18,825 students graduated from universities in Gaza in the academic year 2014-2015. This is nearly 1% of the population of Gaza. Female presence in the academic institutions is equal to that of men. In fact, at Al Azhar University, the female students outnumber the males. About 53% of new students in 2013-2014 were female, and women made up about 54% of graduates that same year.

Female teachers are found in every department. Though many universities in Gaza separate males and females, mixed classes are the norm. Female students are also active in student unions and syndicates.

Unfortunately, the majority of graduates will join the thousands of Gaza’s unemployed. The unemployment rate in Gaza is 41%. The siege imposed in Gaza, the closure of the border, and the destruction of factories, among other things, all contribute to the high number of unemployed. Even if they know finding a job after graduation will be difficult, students continue to enroll. Many will pursue a master’s degree or Ph.D.

In other words, students separate the expected economic outcome of their education from the education itself. Gazan students pursue education for education’s sake . While this might seem positive, in reality it reflects a mismatch between education and the market. Programs are not designed according to the market’s needs. The opening of more universities and colleges contributes to a kind of disorder in the educational system.

Further, vocational education is not given enough attention. With the exception of one community college run by UNRWA, there are no vocational education institutions in Gaza.

A student of mine at Al Azhar University once told me that she did not need to study hard. It would not make a difference if she gets 90% or 60%. In the end she will not find a job regardless of her grades. She was a good student, but she was not sure that her future would be beautiful. She wanted to be sure of her tomorrow. Not all students think the same way, of course, but her frustration reflects the lack of clarity about the future and the inability to believe in it. In spite of this, education still represents a good way to search for the future for the majority of Palestinians in Gaza.

Literary Life in Gaza

One of the unreported faces of Gaza is its rich literary scene. Gaza contributed to Palestinian and Arabic literature with authors and works that are highly acclaimed. Classical literature played a vital role in the making of Palestinian identity and in provoking people to revolt. Thus, there is a kind of Palestinian resistance literature. While the term itself is elusive, one of the many aims of poetry, fiction and theater is to defend the aspirations of the nation. Maybe more than in any other Arab country, authors in Palestine have a very distinguished place in the national memory. Names like Gassan Kanafani, Samih Qassim, Mouen Bessison and the internationally-acclaimed Mahmoud Darwish are not only poets and novelists, they are national figures and heroes.

Gaza has been part of this national culture since the very beginning and has provided Palestinian literature with big names over the last century. In medieval times, Gaza provided the Islamic and Arab world with one of the three major clerics in Islamic theology, the Imam Shafi’ee. In modern times, Gaza witnessed a very dynamic and vivid cultural and literary life. Major Palestinian poets and fiction writers were born and raised in Gaza. The list includes Mouen Bessiso, Mohamad Hassib Qadi, Haroon Haishm Rashid, Ahamd Omar Shaheen and Zaki Al Aila.

Despite today’s hard economic situation, writers in Gaza still try to make their own way. Since there are no publishing houses in the Strip, authors publish their works in printing shops, often out of their own pockets. Few authors make their way to Arab publishing houses. Due to their inability to travel, Gaza’s authors have weak connections with the Arab publishing market. The Palestinian Authority does not fund any cultural and/or arts activities in Gaza, and Hamas has shut down all opposing radio stations, newspapers, etc., leaving authors to struggle to have their voices heard.

Many authors save money for years to have their books published — even locally. Unfortunately, neither the government in Ramallah nor Hamas authorities in Gaza care about this. In addition to that, culture and writing are not on the sexy list for international donors. Even when an international organization allots some funds for cultural programs, these funds are made to fit the organization’s larger mandate, whatever that might be.

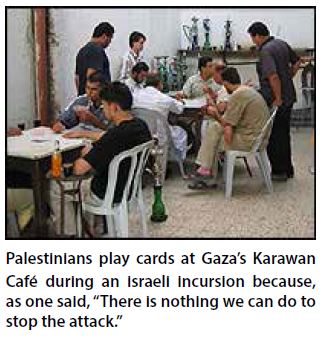

Many local initiatives were taken in the last 20 years. The first was called “Karawan Group,” named after the Karawan café in the Rimal quarter of Gaza. The café is one of the oldest in Gaza. During the 1950s and 1960s, Mouen Bessiso and other local Gazan authors hosted literary activities at the café. In the mid-1990s, a group of authors formed a literary group in the café. For ten years they met every Tuesday to read and discuss their works. Many painting exhibitions were organized at Karawan as well. While the group does not exist anymore, the café still attracts authors and artists who come to sit and share their thoughts.

Another initiative came from a group of female authors and intellectuals. They founded a literary salon called “Noon”. ‘Noon’ in Arabic refers to the feminine. “Salon Noon” has been running for nearly 15 years. The first Wednesday of every month, the women meet to discuss a book, host an author, or talk about literary trends. Over time, the salon started to attract a male audience as its topics are not limited to feminine literature or authors. The two women running the salon, May Naif and Fathia Sorror, both come from the education field. They expanded the target of the salon to include discussions of works of art, cinema, and political contributions by women.

The third initiative that managed to make a difference in Gaza’s literary life is “Utopia,” a literary group which aims to encourage contemporary literature and present the works of the young generation to the audience. Utopia is run by a group of young authors who manage to challenge the absence of any official interest in culture by organizing two festivals in Gaza: one for modern poetry and another for young short story writers. Though Utopia receives some funding from local organizations, it has been mostly funded by the members themselves.

Another group of authors recently decided to publish a literary magazine in Gaza. Previously, poets Authman Hussain and Khalid Jumma’ published a magazine in Gaza devoted to contemporary writing called “Ashtar.” They funded it from their own salaries. Ashtar was a place for all young authors, not just in Gaza but also in the West Bank, to publish their work. Due to a lack of any external funding, the editors had to stop publishing Ashtar. Now a different group of authors are publishing another magazine named “28” to fill the vacuum. “28,” also self-funded, allows fellow authors to have their works read in Gaza. They also try to send copies to the West Bank to expand their readership. For every edition – they are now on their fifth – the editors of “28” organize a meeting where authors gather to discuss their texts.

While many other literary initiatives can be mentioned in this context, one cannot forget the tale of Gaza’s Gallery Café. The Gallery was founded in early 2000 as a café where authors and artists could meet and organize activities, including book launches. However, the authorities in Gaza closed the Gallery in 2008, pretending that the owners of the gardens where the Gallery was located wanted to put something else on the property. A few years later, poet Khaled Shaheen renewed the idea. He rented a place and opened the “Gaza Gallery.” After two years, Shaheen closed the café. He could not afford to keep it open any longer.

Karawan still hosts authors and artists, but now it is more limited to male ones. Thus the need to have something like the Gallery where both men and women can attend activities.

Gaza: Exporter of Short Stories

Short story writing in Gaza flourished after the 1967 Israeli occupation to the extent that it was said that Gaza exports oranges and short stories. This might not be precisely true, but for reasons very peculiar to Gaza, the only literary form that a Gazan author could work in was the short story.

After Israel’s military’s takeover of Gaza, most of the acclaimed authors had to leave the territory because of persecution or deportation by the Israeli forces. In addition, newspapers that were published previously in Gaza were shut down. In other words, literary life and cultural activities nearly disappeared. But not for long. New writers, mostly school teachers in the early 1970s, started a mission to keep literature alive in Gaza.

Poetry needs to be recited in front of audiences, especially when those audiences are under occupation. They love to hear poetry read aloud that addresses their feelings. Novel-writing requires a print shop to take care of publishing and distribution. Since there were no publishers in Gaza, and there were no newspapers or magazines, the only doors open for Gaza’s authors were the publishing houses and newspapers in the West Bank.

And so the only form Gazan writers were left with was the short story. A short story can be written in a few pages which can be easily smuggled and published in newspapers. This did not make them safe from the harassment by the Israeli army. Many authors used pen names. And many of those short stories were full of symbols and allegories, and most importantly, they directly addressed the national struggle and defended national rights. Names like the late Zaki al Ela and Authman Jahjouh, among others, contributed to keeping writing on the stage.

Only in the late 1970s and early 1980s did other forms start to appear. Ironically, even when those authors attempted to write novels in the late 1970s, they were, in fact, writing long short stories. They were affected by the condensed way of writing that they followed in the early years of their writing career. Notwithstanding this, their novels addressed the same topics that their short stories tackled.

After the establishment of the Palestinian Authority in the 1990s, novel writing started to attract more authors and audiences. Long novels of between 200 and sometimes 400 pages appeared. A new generation of poets started to contribute very actively to the emergence of new poetry in Gaza and throughout Palestine. New female authors appeared after being absent for decades. Authors like Donia al Amal Ismael, who now runs the creative women’s organization in Gaza, Summia Soussi, Fatena Al Goura among others all appeared in the 1990s and introduced themselves to the Palestinian literary scene. Today more and more young female authors are writing short stories and plays.

In a book I edited for Comma Press, “The Book of Gaza,” I presented three generations of short story writers in Gaza. Given the Gaza context, it is easy to see the differences that major political events left on their writing.

The first generation started writing in the late 1960s and early 1970s, soon after Israel’s occupation. These writers focused on national issues and values, with simple characters who are overcome with hardship and suffering, yet filled with determination and defiance. The peculiarities of individuals were glossed over in favor of characters speaking on behalf of society as a whole.

When the Palestinian political authority was established, new kinds of power relations within Palestinian society emerged, and the range of themes expanded to express social conflict. I am part of this second generation which started writing in the early 1990s. Characters were no longer simply embodiments of grand ideas. They became more alive, more concerned with human failings and their own pains and dreams. There was a shift from the public to the private in the themes of short fiction.

The third generation started in the last ten years. With modern tools of communication, this younger generation seems more open to the outside world. Personal stories and autobiography emerged, as have intellectual stories that reflect a state of anxiety. Salvation in these stories is a personal matter, in contrast to the heroic, collective liberation for which earlier authors had strived. Feelings of disappointment and the failure to achieve one’s dreams are what have encouraged this generation to delve into themselves and search for individual salvation.

One of the surprises I had while choosing the short stories to be included in the book is the strong presence of women short stories writers nowadays. I wanted to present female authors in my book in order to have a gender perspective, but I did not mean to have as many female authors as I eventually included. I ended up picking five female authors and five male authors. Most of these female authors are young, less than 40 years old. Their stories showed their feminine concerns, the social hardships they face in a male-dominated society, and the female role in the struggle for national and social freedom.

Short story writing is not the main field of literary production these days, but it still attracts many authors. Is there anything peculiar about today’s short stories from Gaza? This question should be answered by the literary critics. But it is evident that the main reasons that made the short story the only literary form available to the authors of Gaza still exist: There are no publishers in Gaza, no way to communicate physically with the outside publisher and to travel to participate in literary festivals outside Gaza. Israeli authorities do not haunt authors in the streets of Gaza or search their houses, but Israel still controls their air, land and sea borders, and prevents them from leaving the country to present their work.

The short story remains a form that can help mitigate the difficulties authors face communicating their work outside the dictatorship of their geography. Short pieces can be posted on Facebook and other social media outlets to be read worldwide. Only then, when the work of Gaza’s authors are read outside, can they truly present a different side of Gaza.

They Have Theater in Gaza

There are no dedicated theaters in Gaza, but theater groups regularly present plays. These groups struggle to survive. Plays are shown in cultural institutions and community centers that have large show rooms. Gaza has two major centers like this: the Rashad Shaw center, named after a prominent mayor of Gaza, and the Mishal center, built by a Palestinian businessman to immortalize his name.

Most of the theater groups receive funds from international donors, while some receive funding from national and local organizations. Given this, many of the plays shown in Gaza deal with issues relevant to the donors’ agenda such as women’s rights, children, and the freedom of expression. Amazingly, however, the last five years witnessed the emergence of a very strong and critical current affairs theater. Plays address courageously the situation in Gaza and are critical of the political authority ruling Gaza. These plays are written and acted by young authors and actors. It is not surprising to see an actress in Gaza without hejab singing and acting like any other actress in the world.

The difficult situation in Gaza, the political division and internal fighting, the siege and the economic and social consequences, the tunnel business, social split, the misuse of religion and the national struggle for freedom are all topics addressed by the new theater in Gaza. Can we call it the theater of the oppressed? I think it is more than that. It is real theater which is angry about everything. In such productions, Gaza’s youth present the difficulties that they face daily. Difficulties which make their future gloomy.

Actor and director Ali Abu Yasseen put it this way: “The actor reflects the reality of his society. Life in Gaza is full of sadness. Our role is to covey this life on the stage so audiences see more clearly the reality round them”.

Abu Yassen’s last play, “The Cage”, talks about the difficulty faced by people living in shelters during war. A girl suffers an injury to her feet and finds no one to help her find treatment. A sympathetic journalist writes a story about her which sparks discussion in Gazan society. The play depicts very critically post 2014 war life in Gaza. It is full of humor and irony, but full of sadness as well, depicting the humanitarian crises at U.N. shelters, the trauma of displaced families and injured people, and how some officials took advantage of the suffering to serve their political self-interests.

Ali is now preparing his new play, titled “Romeo and Juliet in Gaza.” The play presents an ill-fated love story, but not the Shakespearean version.

When I presented my first play back in 2002, an Israeli reviewer wrote “Even they have theater in Gaza,” as if Gaza is not expect to have its own life.

Parkour in Gaza

Parkour, a training discipline using movement developed from military obstacle course training, recently became very popular in Gaza, and it is amazing to watch the young performers jumping and doing crazy movements on the ruins of their destroyed houses.

For these young Gazans, parkour represents an attempt to overcome the limitation of their place. By manipulating their bodies and maximizing their movements — jumping on the roof of a tenth floor building or dancing on a moving car — the practitioners defeat the limits of their bodies and those of their place. Practicing parkour among demolished houses – and sometimes in cemeteries – send political messages about the desire to turn misery into art and joy. It’s as though they are following the advice of their great poet, Mahmoud Darwish, by saying: “Even if our houses are destroyed and even if our dead do not rest because of the damage done to the cemeteries, ‘we still love life as much as we can’.”

Friends living in the same neighborhood film themselves and enjoy seeing their sport in Gaza being viewed by outside audiences. In this way, they practice their sport despite the siege and despite their inability to travel abroad.

Incredibly, some of the teams practiced parkour while Israeli missiles were still hitting the Gaza Strip. After finishing their acrobatic maneuvers, they searched through the wreckage, picking up shards of diffused weapons, cleverly using the heap of ruin to create their own happiness.

Gaza Parkour Team (GPT,) founded in 2005, was the first to appear in Gaza and is composed of 18 members aged between 17 and 25 years-old. Mohammed Aljkhbeer, a cofounder of GPT, believes that parkour frees the practitioners and gives them hope in the difficult situation they are facing. “In this situation we are like caged birds,” he says; “Free running gives us a chance to spread our wings.

“

Though their work travels abroad only through the internet, the team still hopes that one day they will be able to participate in international competitions.

According to, Hamza Shalan, a member of the 3 Run Gaza group, “Feeling free is the best thing about parkour. Everything is closed here for us. In Gaza, with or without war, the situation is so bad. Parkour is my oxygen.”

Though they suffer from a lack of resources, an unsafe environment in which to practice, and an inability to join international competition or invite groups from abroad to visit Gaza, the parkour groups in Gaza are very excited about what they are doing. They believe that by their practice they help to mitigate the severity of the situation.

Painting Gaza

Another story of Gaza is that of the plastic and contemporary arts scene. Like literature, art was part of the national struggle against the occupation. I still remember the scene in 1983 when the niece of the highly acclaimed artist Fathi Gabin was shot and all the camp erupted in protest. Fathi Gabin depicted the funeral of his niece in full details. Gabin, one of the greatest modern Palestinian artists, is my neighbor in Jabalia Camp. I grew up seeing his paintings hung in houses in the camp. His paintings depicted life in the villages from where the refugees were deported. His paintings are known all over Palestine. They were used by the political and resistance movements in the seventies and eighties as posters to provoke people to resist the occupation. He was arrested many times, including a six-month sentence for using the colors black, white, red and green in one of his paintings.

Gaza contributed many important artists to Palestine’s plastic art scene including Tayser Barakat, Mohamd Maqusi, Fayiz Sirsawi, Mohammad al-Hawajiri and Tayser Batninj, among others. Batniji, who now lives in Paris, started performance and installation arts in Gaza. His work ” Breaking News” about the first year of the Second Intifada was pioneering. He presented the negatives of photos of hundreds of people killed during the intifada on a wall. In another room he showed a video of butchers cutting meat. In his next work, titled “Transit,” Batniji showed 5 videos of his attempts to get inside Gaza after a trip he made outside.

A group of artists managed to open their own gallery named “Shababaik” where they present their works and organize discussions.

While writers were not able to overcome the limitations of place, artists did. Literature needs to be translated to be read by foreigners; painting, performance and video art do not. Using online social media, artists from Gaza have succeeded in presenting their work and participating in international galleries even if they did not manage to leave the country.

Gaza’s Grand Piano

In the March 26, 2015 issue of the BBC News Magazine, writer Tim Whewell told a remarkable story. Gaza’s Nawras Theater had been left in ruins following Israel’s 2014 invasion. Yet there, amid the wreckage, on a shattered stage, stood a concert piano, unscathed.

News of the remarkable survival moved Claire Bertrand, a French music technician, to come to Gaza to repair the piano, a job that involved replacing all 230 strings and 88 hammers and felts.

The restoration project was organized by the Brussels-based charity, Music Fund, and financed by the renowned Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim. “Gaza is not only rockets and missiles,” Barenboim told Whewell.

The completion of the restoration was celebrated with a concert by Gaza’s only music school, a branch of Palestine’s Edward Said National Conservatory. Seated at the refurbished piano, performing Beethovan’s 19th piano sonata, was 15-year-old Sara Aqel. “Music,” said the teenager who, like the piano, had lived through three wars, “might not build you a house or give you your loved-ones back. But it makes you feel better, so that’s why I just keep playing it.”

Lukas Pairon of Music Fund put it this way: “Music in Gaza is a form of rebellion against being narrowly defined as living beings who only want the basic things — food, protection, security — who are only in survival mode.”

Hip Hop in Gaza

Jackie Salloum is a young Palestinian-American who, in 2001, moved from Dearborn, MI to New York City to pursue a graduate degree at the renowned Steinhardt art school.

A year later, she heard Palestinian hip hop for the first time on radio and was transfixed. In 2003, she travelled to Beit Jala and began filming what would turn out to be her widely acclaimed 80-minute documentary “Slingshot Hip Hop.”

The project however, was costly and, when she ran out of money, she had to move back home with her parents and work at the family’s ice cream store. As she told Al Jazeera in a Nov. 7, 2008 interview, “I would scoop during the day, edit at night, and take all of the profit from the ice cream parlor. That’s why, in the end of the film, you will read ‘Fresh Booza (ice cream in Arabic) Productions,’ in homage to them.”

The documentary, which had its world premiere at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival, shows how young Palestinians in Gaza, the West Bank and inside Israel use hip hop to surmount the daily challenges imposed by the circumstances of their lives.

In Gaza, Mohammed al-Farra from the group Palestinian Rapperz, explains in the film that for him rapping is a form of release from Israel’s ceaseless repression. This included being shot in the arm by an Israeli-fired bullet that narrowly missed his heart.

Another Gazan rapper we meet in the film is Ibrahim, who comes from a largely destroyed residential area in Southern Gaza. He raps seeing “all of the colors of the rainbow” at night, thanks to Israel’s constant bombardment. His resistance is generational: his father was imprisoned for performing songs with a subversive political message.

Reviewing “Slingshot Hip Hop” for the website The Electronic Intifada, Maureen Clare Murphy wrote: “It is in large part the resistance of everyday people to the obliteration of their society and national identity that has kept the Palestinian nation alive despite the tribulations of Palestinian politics…Jackie Salloum’s most recommended film helps ensure that Palestinian hip hop claims its rightful place in the proud tradition of artistic resistance to oppression.

In Praise of Women and Society

Despite the Islamization of the society and the Islamic nature of the authority that controls it, Gaza has a strong civil society and vibrant women’s movements.

In the absence of a national government since 1948, non-governmental organizations were established to advocate for the interests of the people. Most of those organizations were linked to national movements and had political motivations alongside their benevolent role. Though centralized in Gaza City, many small organizations were founded in the rural areas and in the refugee camps. They cover many fields and sectors including education, agriculture, human rights, health, mental health, culture and the arts.

With the establishment of the Palestinian Authority, international aid was diverted to the nascent government. Civil society organizations nonetheless continued to pursue their missions and, in one way or another, started to play the role designated to normal civil societies in normal states: that of filling the space between the state organs and the citizen.

Things started to be more complicated when Hamas took over the Gaza Strip in June 2007. Hamas was torn between two desires. On one hand, it wanted to apply Islamic law to every tiny detail of life in Gaza. Sharia was expected to be the law that an Islamic party adhered to. At least its constituents and supporters expected that. On the other hand, Hamas realized that doing so would provoke its political and social opponents and, more importantly, would bring more regional and international criticism.

Notwithstanding this, Hamas tried to test its ability to let such laws go smoothly without adopting a general strategy. Thanks to the civil society and the nongovernmental organizations, those laws were not applied in full. One can expect that without the strong opposition of civil society, Hamas would have turned most of the laws applied in Gaza to Sharia. One example is not allowing women to smoke argila ( the hookah or waterpipe) in the cafés in Gaza. Cafés were told not to offer women argila. Women’s organizations stood firmly to fight against the law. After this pressure, Hamas authorities in Gaza had to retreat.

Another example is Hamas’s attempt to impose hejab (the headscarf) on the schools in Gaza. It was reported that girls were not allowed to enter their classes unless they wore hejab. Officially, the government denies that it adopted such a policy and what happened came from the personal preferences of the schools’ staff. Today, most adult girls wear hejab in schools, although some do not, especially in the modern quarters of Gaza City. There are numerous reports that those who do not wear hejab are subject to harassment and punishment, especially in the schools run by the government.

Virtual Gaza

With the outbreak of the so-called Arab Spring, social media played a great role in mobilizing the youth to revolt against the dictator regimes. Without social media it would be hard to imagine the massive youth participation in the demonstrations that Arab capitals witnessed before being transformed into a military struggle.

Palestinian youth were not an exception. Thousands of young men and women went out in the streets of the city of Gaza and Ramallah asking for the end of the political division between Fateh and Hamas. The social media call for a march on 15 March 2011 started in Gaza, and the main organizers of the youth demonstrations were Gazan.

The major demonstration took place in the “Unknown Soldier” garden in Gaza City. After the end of the demonstration, social media activists in Gaza formed a youth group named the “15 March” coalition to end the division and to defend youth rights. The coalition still organizes many activities and uses social media outlets to mobilize young people in Gaza.

Gaza is under siege. The people there cannot move outside the Strip easily and thus have a tendency to use social media to communicate with the outside world. Social media websites provide the youth in Gaza an alternative to compensate for their inability to leave the territory. Long before the Arab spring, Gazans used Facebook and Twitter to mobilize activists and political supporters as well as general audiences for political activities or other public events. The Internet offered a new, accessible and inexpensive tool to share ideas with the world and to communicate with its citizens.

The virtual space offered the Gazans a freedom that has been stripped by their actual geography. Internet cafés have been common in the streets of Gaza since the early 2000s. Even though most houses are connected to the Internet these days, Internet cafés are still places where teenagers spend their time in the evenings.

The information technology market in Gaza is flourishing. Graduates from IT faculties have found a way to earn money through developing programs and software without the need to cross borders. IT offers them a chance to work with international clients without being troubled with the limitation of their place. The space offered by the Internet helps them to overcome their actual space.

This difference between virtual and actual space is very distinct in Gaza. It is the difference between a place that exists but makes people unable to exist inside it, and a place that does not exist but offers the people a chance to exist nonetheless. This mirrors the dichotomy that dominates the lives of the young in general: their bodies are in one place while their dreams are fulfilled in another.

This is the same paradox that makes the sea in Gaza another borderline rather than a huge gate to communicate with the outside world.

The sea is little more than a nice painting hung on the wall in Gaza. It is very beautiful to look at, but you always have to remember that it is not more than a painting.

You cannot cross the sea. Even if you sail in the sea and fish from it, you have always to remember that this might be an imaginary trip inside a painting. It is as if the painter decided that you can be part of his painting. Thus even when others view the sea while sitting on the beach, they are very sure about you being part of the painting.

On the other side, you know that the painter is not free to do so. There is always an intruder who will, at certain points, intervene with gunships to kick you out of the scenery.

You have to remember your limits.

Even when you want to enjoy the sea, you have to look deeply in the horizon to discover the gunships pointing their guns towards Gaza, ready to devastate it at any time.

In the 2014 assault, kids from the family of Baker were killed while playing football on the beach.

Earlier, in 2006, the child Hudia Ghalia was killed in front of the camera while enjoying a summer evening with her family.

You have to remember your limits.

Kind of Final Remarks

And there are limits for everything in Gaza. Limits you have to remember by heart and learn to adapt to. Limits to your ability to cross the place and to move freely within it. Limits to enjoy your time inside it. Limits to see its beauty.

If you fail to understand these limits, you risk losing your life.

The only available venue is your imagination. You can live in your imagined world. In other words, you make up your own virtual place. A place that does not exist outside your mind.

There you can survive. There you can enjoy the limitlessness of the place. There you can have your dreams fulfilled.

In this place, Gaza would have free access to the outside world. It would have a true sea, a sea that you can sail from to all ports of the Mediterranean.

There you can have your family, friends and neighbors enjoy being part of your life.

You can invite friends from outside to visit you, to show them your place and guide them to the historical and religious sites.

Only there, the true Gaza might exist.

But the minute you do this, you feel more sure that this world does not exist.

Unfortunately, Gaza is reduced to a piece of news. What attracts media attention is what the occupation is making out of Gaza, not the actual Gaza. The different Gaza – the second Gaza — is hidden from the scene by the occupation machine.

I remember when I started to write my dairies during the 2008 assault on Gaza, the first words that came to mind were “I do not want to be a number.” The diaries were not published. Two other assaults took place in 2012 and 2014 and still I screamed “I do not want to be a number.” I wrote the same phrase in my 2014 wartime dairies. I always had a strong feeling that the media wants to transform me into a number. Victims are made into numbers. Destroyed house are made into numbers. Schools and streets. Mosques and churches. Everything is made to fit the media machine. In this process of “numbering,” rich stories about life, love, passion and dreams are lost. It is easy to say that 50 people were killed in an Israeli attack on Gaza. The 50 different lives full of memories and unfulfilled dreams are not mentioned. The media pursues its digital occupation. It dehumanizes the occupied people. It makes them another part of the machine.

And the richness of the place is lost and the human activities of its people are not spoken about.